The Complete Guide to PCR and RT-PCR Amplification Efficiency: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Troubleshooting

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for understanding, optimizing, and validating PCR and RT-PCR amplification efficiency.

The Complete Guide to PCR and RT-PCR Amplification Efficiency: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Troubleshooting

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for understanding, optimizing, and validating PCR and RT-PCR amplification efficiency. Covering foundational principles to advanced methodologies, the article details proven strategies for troubleshooting common amplification problems, including poor yield, non-specific products, and inhibitor effects. It further explores rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of reagents and protocols to ensure reliable, reproducible results for critical applications in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. The content integrates the latest optimization techniques and MIQE-guided best practices to empower professionals in achieving robust, high-efficiency amplification.

Understanding PCR Amplification Efficiency: Core Principles and Critical Metrics

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) efficiency is a critical parameter that quantifies the effectiveness of the amplification process in each cycle of a PCR reaction. In an ideal reaction, the amount of target DNA doubles every cycle, resulting in 100% efficiency. In practice, however, various factors can cause efficiency to drop below or, artifactually, rise above this theoretical maximum. Understanding, calculating, and troubleshooting PCR efficiency is fundamental for obtaining accurate and reproducible quantitative data, especially in gene expression studies, diagnostic assays, and drug development research. This guide provides a comprehensive troubleshooting resource to help researchers identify and resolve issues related to PCR efficiency.

FAQs on PCR Efficiency

1. What is PCR efficiency and why is it important?

PCR efficiency (E) is the fraction of template molecules that is amplified in a single PCR cycle [1]. It is a crucial indicator of reaction performance. Optimal efficiency (90-110%) ensures that the calculated difference in starting template quantity between samples is accurate [2] [3]. Poor efficiency leads to significant underestimation or overestimation of target levels, compromising data reliability in sensitive applications like relative quantitation of gene expression.

2. How do I calculate the efficiency of my PCR assay?

The most common method involves creating a standard curve from a serial dilution of a known template amount. The efficiency is then calculated from the slope of the curve using the formula: E = 10^(–1/slope) – 1 [2] [3].

The following table summarizes the interpretation of the slope and its corresponding efficiency:

| Standard Curve Slope | PCR Efficiency (%) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| -3.32 | 100 | Ideal amplification [1] |

| -3.6 to -3.3 | 90 - 110 | Acceptable range [4] |

| Below -3.6 (e.g., -3.8) | < 90 | Poor efficiency; requires troubleshooting [4] |

| Above -3.3 (e.g., -2.9) | > 110 | Artifactual efficiency; indicates inhibition or errors [4] [3] |

3. My PCR efficiency is below 90%. What are the most common causes?

Suboptimal efficiency is frequently caused by issues that hinder the polymerase enzyme or primer binding. The primary culprits are:

- PCR Inhibitors: Contaminants in the sample, such as phenol, ethanol, heparin, or proteins, can inhibit the DNA polymerase [4] [5].

- Poor Primer/Probe Design: Primers with secondary structures (hairpins), self-complementarity (primer-dimers), or suboptimal melting temperatures (Tm) lead to inefficient annealing [4] [6].

- Suboptimal Reaction Conditions: Inaccurate Mg²⁺ concentration, insufficient DNA polymerase, or inappropriate annealing temperature can all reduce efficiency [7] [8].

4. Can PCR efficiency be greater than 100%? What does it mean?

While thermodynamically impossible, calculated efficiencies above 110% are commonly observed. This artifact typically indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors in the more concentrated samples of your standard curve [3]. The inhibitors cause a delay in the Ct value for concentrated samples, flattening the slope of the standard curve and leading to a calculated efficiency over 100% [4] [3]. Diluting the sample often removes the effect of the inhibitor and restores a proper slope.

5. How does PCR efficiency affect the ΔΔCt method for relative quantification?

The standard ΔΔCt method assumes that the efficiency of the target and reference genes is 100% (or at least equal and close to 100%). If the efficiencies are not the same, this method will produce inaccurate results [1] [2]. The error can be significant; for example, with a true efficiency of 90% at a Ct of 25, the calculated expression level can be 3.6-fold less than the actual value [2]. It is critical to validate that your assays have similar and high efficiency before using the ΔΔCt method.

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor PCR Efficiency

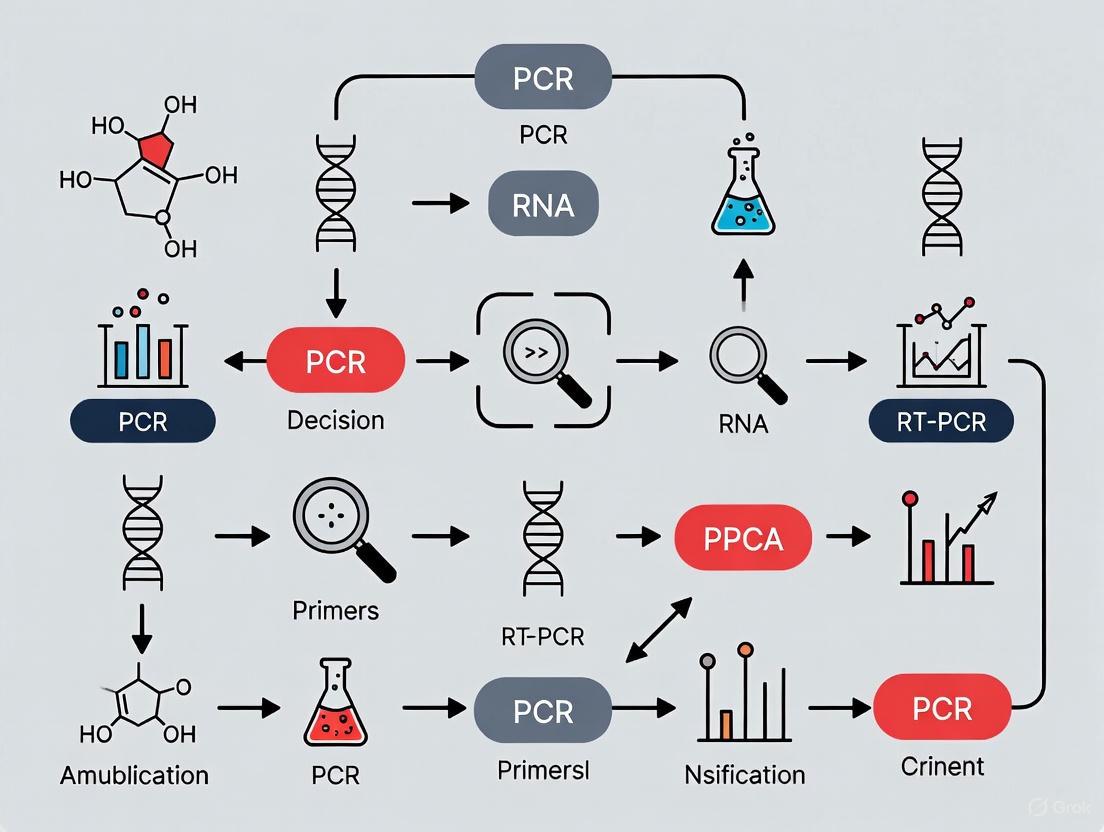

Use the following flowchart to diagnose and resolve common PCR efficiency issues. This systematic approach helps identify the root cause, from sample quality to data analysis.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing PCR Efficiency

This section provides a detailed methodology for determining the amplification efficiency of your qPCR assay, which is a critical first step in any rigorous quantification experiment.

Objective

To generate a standard curve through serial dilutions of a template and calculate the PCR amplification efficiency and correlation coefficient (R²) for a specific primer pair.

Materials and Reagents

The following table lists the essential components for a standard qPCR efficiency experiment.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Specification & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, and optimized buffer. | Use a hot-start polymerase for specificity. Ensure it is compatible with your detection chemistry (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan) [7]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Binds to the target sequence for amplification. | Designed for uniqueness and optimal Tm (e.g., 18-25 bases, 40-60% GC content). Avoid dimers and secondary structures [6] [9]. |

| Template DNA/cDNA | The target nucleic acid to be amplified. | For the standard curve, use a high-concentration, pure sample (e.g., plasmid, genomic DNA, or cDNA). Quantify via spectrophotometry [4]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent to bring the reaction to final volume. | Ensures no enzymatic degradation of reaction components. |

| Optical Plate & Seals | Vessel for the reaction. | Compatible with your real-time PCR instrument. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Prepare Template Dilutions: Create a minimum of 5-point, 10-fold serial dilution series of your template (e.g., from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁵). Use a high-quality, known-concentration stock and nuclease-free water as the diluent [4] [2]. Accurate pipetting is critical for a valid standard curve.

Prepare qPCR Reactions:

- Calculate the required number of reactions (including triplicates for each dilution point and a no-template control (NTC)).

- Prepare a master mix containing all common components (master mix, primers, water) to minimize pipetting error and ensure consistency [6].

- Aliquot the master mix into the optical plate.

- Add the respective template from each dilution tube to the designated wells. Add nuclease-free water to the NTC well.

Run Real-Time PCR: Seal the plate, centrifuge briefly to collect contents, and place it in the thermocycler. Use the cycling conditions recommended for your master mix and primers. A typical two-step cycling protocol is shown below.

- Data Analysis:

- Use the real-time PCR instrument's software to determine the Ct (threshold cycle) value for each well.

- Generate a standard curve by plotting the Ct values (Y-axis) against the logarithm of the starting template quantity or dilution factor (X-axis).

- The software will typically provide the slope and the correlation coefficient (R²) of the linear regression line. A high R² value (≥0.99) indicates a precise dilution series [4].

- Calculate the PCR efficiency (E) using the formula: E = 10^(–1/slope) – 1.

Expected Outcomes and Interpretation

- Ideal Result: Slope ≈ -3.32, Efficiency ≈ 100%, R² ≥ 0.99. The assay is highly efficient and precise.

- Acceptable Result: Slope between -3.6 and -3.3, Efficiency between 90% and 110%, R² ≥ 0.98. The assay is acceptable for most relative quantification experiments.

- Action Required: Slope outside the -3.6 to -3.3 range, Efficiency <90% or >110%, R² < 0.98. The assay requires troubleshooting following the guide above before proceeding with experimental samples.

For researchers and scientists in drug development, achieving precise and reliable quantification in quantitative PCR (qPCR) is paramount. At the heart of this reliability lies a key metric: amplification efficiency. PCR efficiency refers to the fold-increase of amplified product during each cycle of the PCR reaction, with an ideal range of 90-100% considered the gold standard for reliable quantification [10]. This range corresponds to an efficiency value (E) of 1.9 to 2.0, meaning the DNA quantity nearly doubles with each cycle.

When efficiency falls within this optimal window, the reactions are highly reproducible, and the data analysis—whether using absolute quantification, relative expression, or the ΔΔCq method—is mathematically sound [10]. This ensures that comparisons between samples, treatments, or time points are accurate and biologically meaningful. Deviations from this ideal range can introduce significant bias, compromising experimental conclusions, especially in sensitive applications like viral load quantification, gene expression analysis in preclinical models, or biomarker validation [11] [12].

Diagnosing Sub-Optimal Efficiency: Key Questions & Answers

FAQ: How can I quickly diagnose an efficiency problem in my qPCR data?

You can identify potential efficiency issues by examining your standard curve. A slope between -3.1 and -3.3 (corresponding to 90-110% efficiency), an R² value >0.99, and a y-intercept within a consistent range are indicators of a robust assay [13]. Significant deviations from these values suggest a problem.

FAQ: My amplification curves have a sigmoidal shape. Is that sufficient to confirm good efficiency?

No, a sigmoidal shape is necessary but not sufficient. You must generate a standard curve from a serial dilution of a known template quantity to calculate the actual efficiency [10]. Plot the Cq values against the logarithm of the template concentration. The slope of this line is used in the formula: Efficiency % = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) * 100%.

FAQ: What are the immediate consequences of low PCR efficiency in my drug treatment experiment?

Low efficiency directly reduces the sensitivity of your assay, making it difficult to detect small but biologically relevant changes in gene expression or pathogen load [11]. Critically, it invalidates the core assumption of the ΔΔCq method, leading to an underestimation of the true fold-change between your control and treated samples [10].

The following workflow provides a systematic guide for diagnosing and troubleshooting sub-optimal PCR efficiency:

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Efficiency Problems

The table below outlines common causes of sub-optimal PCR efficiency and their respective solutions, synthesized from leading technical guides.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer/Probe Design | Non-specific binding or primer-dimer formation [14] | Redesign primers using validated software; avoid complementary 3' ends. Check ΔG for dimer formation (should be ≥ -2.0 kcal) [14]. | Ensures specific amplification of the intended target, minimizing side reactions that consume reagents and skew efficiency. |

| Primer/Probe Concentration | Sub-optimal concentration leading to poor kinetics [14] [12] | Perform concentration optimization (typical range 50–800 nM for primers; 100–250 nM for probes) [14]. | Provides an optimal molar ratio for polymerase binding and extension, maximizing the rate of product formation per cycle. |

| Reaction Components | Impure template or PCR inhibitors [7] | Re-purify template DNA (e.g., ethanol precipitation); use polymerases with high inhibitor tolerance. | Removes contaminants that sterically hinder polymerase activity or degrade reaction components. |

| Mg²⁺ Concentration | Incorrect Mg²⁺ level [7] [15] | Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration in 0.2–1 mM increments. Note that MgSO₄ is preferred for some polymerases (e.g., Pfu) [7]. | Mg²⁺ is a essential cofactor for polymerase activity; its concentration directly affects enzyme fidelity and processivity. |

| Thermal Cycling | Sub-optimal annealing temperature (Ta) [7] [14] | Determine primer Tm accurately; use a gradient cycler to test Ta in 1–2°C increments, usually 3–5°C below the Tm [7]. | An optimal Ta ensures primers bind specifically to their target sequence, preventing non-specific amplification and improving yield. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful optimization requires the right tools. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in achieving optimal PCR efficiency.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until a high-temperature activation step [7] [15]. | Essential for complex templates (e.g., genomic DNA) and multiplex assays. Improves specificity and yield. |

| PCR Optimization Kit (e.g., Buffers A-H) | Provides a range of pre-formulated buffer conditions with varying salt and additive concentrations to empirically determine the optimal chemical environment for a specific primer-template pair [13]. | Streamlines the process of optimizing Mg²⁺, salt, and additive conditions without manual titrations. |

| GC Enhancer / Co-solvents | Additives like DMSO, formamide, or proprietary GC enhancers help denature GC-rich templates and resolve secondary structures that hinder polymerase progression [7] [15]. | Critical for amplifying difficult targets with high GC content or strong secondary structures. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | DNA polymerases with proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity offer higher fidelity, reducing misincorporation errors that can lower effective efficiency and introduce sequence errors [15]. | Preferred for cloning and sequencing applications where sequence accuracy is critical. |

| Magnetic Bead-based Cleanup Kits | For purifying template DNA or PCR products to remove salts, enzymes, and other inhibitors (e.g., from blood, soil, plant tissues) that can carry over into the reaction [7] [11]. | Simple and effective method to ensure template purity, a common factor in failed or inefficient reactions. |

Advanced Optimization: A Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

This detailed protocol is designed for systematically troubleshooting and optimizing a qPCR assay that is showing sub-optimal efficiency.

Objective: To identify the optimal combination of annealing temperature (Ta) and primer concentration for a new qPCR assay, aiming for 90-110% amplification efficiency.

Materials:

- Template DNA (e.g., a validated positive control sample)

- Forward and Reverse Primers, Probe (if using)

- Optimization PCR Buffer Kit or Master Mix with customizable Mg²⁺

- Thermostable DNA Polymerase

- dNTP Mix

- Nuclease-free Water

- Real-time PCR Instrument with gradient functionality

Procedure:

Primer Quality Control: Resuspend primers to a high concentration (e.g., 100 µM) in nuclease-free water or TE buffer. Verify concentration spectrophotometrically and store in single-use aliquots to prevent freeze-thaw degradation [7].

Initial Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing all common components (buffer, polymerase, dNTPs, water, template). Aliquot this master mix into individual PCR tubes or a multi-well plate.

Primer Concentration Matrix: As visualized in the diagram below, create a two-dimensional optimization matrix. Test a range of forward and reverse primer concentrations (e.g., 50 nM, 200 nM, 400 nM, 600 nM) against a range of annealing temperatures (e.g., 55°C to 65°C) using the thermal cycler's gradient function [14].

qPCR Run and Data Collection: Run the qPCR protocol with a melt curve analysis step at the end. Record the Cq value, calculate the amplification efficiency (from a standard curve if included, or observe the raw Cq shift across a dilution series), and analyze the melt curve for a single, specific peak.

Data Analysis and Selection: The optimal condition is the combination of lowest primer concentration and highest annealing temperature that produces the earliest Cq value, an efficiency between 90-110%, and a single peak in the melt curve, with no amplification in the no-template control (NTC) [14]. This combination ensures high sensitivity, specificity, and reagent economy.

The Future of Efficiency Control

Traditional optimization addresses reagent and cycling conditions. However, emerging research highlights an intrinsic challenge in multi-template PCR (e.g., in microbiome studies or high-throughput sequencing): sequence-specific amplification bias. Even with optimized universal conditions, different DNA templates can amplify at vastly different efficiencies based solely on their sequence, leading to skewed quantitative data [16].

A groundbreaking 2025 study used deep learning (1D-CNNs) to predict a sequence's amplification efficiency based solely on its nucleotide sequence. The model identified that specific sequence motifs near the primer binding sites, which can lead to adapter-mediated self-priming, are a major cause of poor efficiency [16]. This AI-driven approach paves the way for the in silico design of amplicon libraries with inherently more homogeneous amplification, potentially revolutionizing quantitative accuracy in complex multi-target applications. This represents the next frontier in moving from troubleshooting efficiency post-hoc to designing it into our experiments from the start.

The Core Relationship: Slope and Efficiency

In quantitative PCR (qPCR), the standard curve is a fundamental tool for assessing the performance of your amplification reaction. The slope of this curve, generated by plotting the Cycle Threshold (Ct) values against the logarithm of the known template concentrations, has a direct mathematical relationship with PCR efficiency [1] [2].

The efficiency (E) of a PCR reaction is calculated from the slope using the following formula: E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1

This efficiency is frequently expressed as a percentage: Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) × 100

The following table summarizes the key quantitative relationships between slope, efficiency, and reaction performance:

| Standard Curve Slope | PCR Efficiency (Value) | PCR Efficiency (%) | Theoretical Amplification per Cycle | Performance Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -3.32 | 2.00 | 100% | 2 (doubling) | Ideal [1] |

| -3.58 | 1.90 | 90% | 1.9 | Acceptable Range [2] |

| -3.10 | 2.08 | 108% | ~2.1 | Acceptable Range [2] |

| Less than -3.58 (e.g., -3.8) | Less than 1.90 | <90% | Less than 1.9 | Low efficiency; requires troubleshooting |

| Greater than -3.10 (e.g., -2.9) | Greater than 2.15 | >115% | More than 2.15 | High efficiency; may indicate inhibition or artifacts [3] |

This relationship is foundational because the ΔΔCt method of relative quantification assumes an efficiency of 100% (slope of -3.32). A deviation from this ideal slope introduces significant errors in the calculated gene expression levels [2]. For example, an efficiency of 90% instead of 100% can lead to a 261% error at a Ct of 25, meaning the calculated expression level could be 3.6-fold less than the actual value [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Slope and Efficiency Issues

What should I do if my calculated efficiency is below 90%?

Low PCR efficiency (steep slope) is often a sign of suboptimal reaction conditions that prevent the reagents from functioning properly.

- Possible Cause: Problematic Primer Design or Quality. Primers with secondary structures (like hairpins or dimers), non-optimal melting temperatures (Tm), or consecutive G/C nucleotides at the 3' end can lead to poor annealing and inefficient amplification [7] [3].

Solutions:

- Redesign Primers: Verify that primers are specific to the target and have minimal complementarity to each other. Use online primer design tools and ensure the Tm is appropriate for your polymerase and buffer system [7] [17].

- Check Primer Quality: Use purified primers to remove truncated oligos that can inhibit the reaction. Aliquot primers after resuspension to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [7].

- Optimize Annealing Temperature: Perform a gradient PCR to determine the optimal annealing temperature for your primer set. Increasing the temperature can improve specificity, while decreasing it can aid binding if the temperature was too high [7] [18].

Possible Cause: Suboptimal Reaction Components. The concentration of key components, particularly Mg²⁺, is critical for polymerase activity.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Mg²⁺ Concentration: Mg²⁺ is a cofactor for the DNA polymerase. Test concentrations in 0.2-1 mM increments to find the optimum. Excess Mg²⁺ can reduce fidelity and promote non-specific amplification, while too little can inhibit the enzyme [7] [18].

- Ensure Fresh, High-Quality Reagents: Use fresh dNTPs and ensure their concentrations are balanced, as unbalanced nucleotides increase the error rate. Prepare new working aliquots if you suspect degradation [7] [18].

- Verify Template Quality/Purity: Assess template DNA integrity by gel electrophoresis and check for contaminants like phenol, EDTA, or proteins that can inhibit the polymerase. Re-purify the template if necessary [7] [19].

What does an efficiency significantly above 100% indicate?

While an efficiency slightly above 100% can fall within an acceptable range, a value substantially exceeding 110% (shallower slope) often points to specific experimental artifacts [3].

- Possible Cause: PCR Inhibition in Concentrated Samples. This is a primary reason for artificially high calculated efficiencies. If inhibitors (e.g., heparin, hemoglobin, salts, or residual organics from purification) are present in your more concentrated standard samples, the Ct values will be delayed compared to expectations. As the standard series is diluted, the inhibitors are also diluted, reducing their effect and causing a flattening of the standard curve slope [3].

Solutions:

- Dilute the Template: Diluting the sample can reduce the concentration of inhibitors to a level that no longer affects the reaction. If the problem is resolved with dilution, inhibition was likely the cause [3].

- Purify the Sample: Re-purify your nucleic acid template using ethanol precipitation or a dedicated clean-up kit to remove potential inhibitors [7] [19].

- Use a Robust Master Mix: Consider using a polymerase or master mix formulated to be more tolerant of common inhibitors found in biological samples [7] [20].

Possible Cause: Pipetting Errors or Inaccurate Dilution Series. Inconsistencies in preparing the standard curve are a common source of error.

- Solutions:

- Check Pipette Calibration: Ensure pipettes are properly calibrated and use good technique, especially when creating serial dilutions [1].

- Prepare Fresh Dilutions in a Stabilizing Buffer: To prevent DNA from adsorbing to tube walls and skewing concentrations, dilute standards in a buffer containing a chelating agent (e.g., 0.1 mM EDTA) and a detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween-20). Avoid freezing diluted standards; keep them at 4°C and prepare fresh batches regularly [21].

How can I visually assess efficiency from an amplification plot?

Beyond calculating from a standard curve, you can get a quick assessment of efficiency by examining the amplification curves [1].

- Protocol for Visual Assessment:

- Plot your qPCR data with fluorescence on a logarithmic (log10) Y-axis and cycle number on the X-axis.

- Observe the exponential phase of the curves. Reactions with 100% efficiency should have parallel slopes during this phase [1].

- Compare the slopes of your samples to each other, or to an assay known to have 100% efficiency (e.g., a verified reference gene assay). Non-parallel slopes indicate differences in amplification efficiency between assays [1].

This visual method is not a replacement for a proper standard curve validation, but it offers a rapid way to identify potential efficiency problems without additional experiments and is not impacted by pipette calibration errors [1].

Experimental Protocol: Determining Your qPCR Assay Efficiency

This protocol provides a detailed method for establishing a standard curve to calculate the amplification efficiency of your qPCR assay.

Principle: By amplifying a known quantity of template DNA across a serial dilution, a linear relationship between the log of the starting quantity and the Ct value is established. The slope of this line is used to calculate PCR efficiency [2].

Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Quantified DNA Template | The target used to create the standard dilution series (e.g., gBlock, plasmid, PCR product). |

| qPCR Master Mix | A ready-to-use mix containing buffer, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, hot-start polymerase, and a reference dye if required. |

| Sequence-Specific Assay | Primers (and probe, if using a probe-based chemistry) designed for your target. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for creating dilutions and completing reaction volume. |

| Real-Time PCR Instrument | The equipment used to run the thermal cycling and detect fluorescence. |

| Dilution Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 8.0) | A buffer to prevent degradation and adsorption of DNA in dilute standards [21]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Prepare Standard Dilutions:

- Start with a stock solution of your DNA template of known concentration (e.g., 10 ng/µL).

- Perform a serial dilution (e.g., 1:10 or 1:5 dilutions) in the recommended dilution buffer to create at least 5 points covering the dynamic range you expect in your experimental samples [2]. A 7-point, 10-fold dilution series is considered ideal for a robust curve [1].

- Critical Note: Avoid freezing these diluted standards. Store them at 4°C and prepare a fresh batch for each new standard curve to ensure accuracy [21].

Set Up qPCR Reactions:

- For each standard dilution point, prepare replicate reactions (at least duplicates, triplicates are better).

- Include a no-template control (NTC) containing nuclease-free water instead of DNA to check for contamination.

- Use a consistent reaction volume according to your master mix protocol.

Run the qPCR Program:

- Use the thermal cycling conditions optimized for your primer set and master mix. This typically includes:

- Initial Denaturation: 1 cycle (e.g., 95°C for 2-10 minutes)

- Amplification: 40-45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10-30 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (temperature and time depend on the assay)

- Use the thermal cycling conditions optimized for your primer set and master mix. This typically includes:

Analyze the Data:

- The instrument software will typically generate a standard curve automatically.

- Record the Slope (S) and the R² value (coefficient of determination, which should be >0.98 for a linear series) from the standard curve.

- Calculate Efficiency: Use the formula E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 to determine the efficiency of your assay.

Workflow for Determining qPCR Efficiency

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this experiment, from setup to data interpretation and subsequent action.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents is critical for achieving optimal qPCR performance. The table below details key solutions for troubleshooting efficiency problems.

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in Troubleshooting Efficiency |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup by inhibiting polymerase activity at room temperature, thereby improving specificity and yield [7] [19]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., GC Enhancer, BSA, Betaine) | Helps denature GC-rich templates and sequences with secondary structures, improving amplification efficiency of difficult targets. BSA can also bind to inhibitors present in the sample [7] [19]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Polymerase Blends | Specially formulated enzymes with high processivity and tolerance to common PCR inhibitors carried over from complex biological samples like blood, soil, or plant tissues [7] [20]. |

| UDG/UNG Decontamination System | Uses Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG/UNG) with dUTP-substituted nucleotides to degrade carryover amplicon contamination from previous PCRs, preventing false positives and maintaining accurate Ct values [22]. |

Essential Reaction Components and Their Roles in Efficiency

In the context of troubleshooting PCR and RT-PCR amplification efficiency, a deep understanding of each reaction component is paramount. Even minor deviations in the quality, concentration, or handling of these components can lead to experimental failure, resulting in issues such as no amplification, non-specific products, or poor fidelity. This guide details the essential building blocks of these reactions, explaining their precise roles and how they interact to determine the overall success and efficiency of your amplification experiments. The following sections provide a systematic, question-and-answer style troubleshooting framework to help researchers and drug development professionals identify and resolve common challenges.

FAQ: Core Reaction Components and Troubleshooting

What are the essential components of a PCR reaction, and what are their optimal concentrations?

A standard Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) requires a precise mixture of several core components, each playing a critical role. The table below summarizes these components, their functions, and their typical optimal concentrations in a 50 µL reaction.

Table 1: Essential PCR Components and Their Roles [6] [23]

| Component | Function | Recommended Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Template | The target sequence to be amplified. | 104–107 molecules (∼1–1000 ng for genomic DNA) [6] [23] |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | Short DNA sequences that define the start and end of the amplification region. | 0.1–1 µM each (typically 20–50 pmol per reaction) [7] [6] [23] |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding nucleotides. | 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [7] [6] |

| Mg2+ | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. | 0.5–5.0 mM (often supplied with buffer; requires optimization) [7] [23] |

| dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) | The four nucleotide building blocks for new DNA strands. | 20–200 µM of each dNTP (typically 200 µM total) [6] [23] |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal pH and ionic conditions (e.g., KCl) for enzyme activity. | 1X concentration [6] [23] |

| Sterile Water | Brings the reaction to its final volume. | Quantity sufficient (Q.S.) |

How does the choice of DNA polymerase influence PCR efficiency and specificity?

The DNA polymerase is the core enzyme of the reaction, and its properties directly impact success. Selecting the right polymerase is crucial for challenging templates or specific downstream applications.

Table 2: DNA Polymerase Properties and Selection Guide [7] [23]

| Property | Impact on PCR | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostability | Determines how well the enzyme withstands high denaturation temperatures. | For high-temperature denaturation, use polymerases from hyperthermophiles (e.g., Pfu polymerase) [23]. |

| Fidelity (Error Rate) | The accuracy of DNA synthesis. Critical for cloning and sequencing. | Use high-fidelity polymerases with 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity (e.g., Q5, Phusion) for applications requiring low error rates [7] [24]. |

| Processivity | The number of nucleotides added per enzyme binding event. | For long targets or difficult templates (e.g., high GC-content), choose polymerases with high processivity [7]. |

| Hot-Start | Prevents enzymatic activity at room temperature. | Use hot-start DNA polymerases to suppress non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [7] [19]. |

Which additives can improve the amplification of difficult templates?

Difficult templates, such as those with high GC-content or complex secondary structures, often require specialized additives. These co-solvents help by altering DNA melting behavior or polymerase stability.

Table 3: Common PCR Additives for Challenging Templates [7] [23]

| Additive | Function | Recommended Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Disrupts base pairing, helping to denature GC-rich regions and reduce secondary structures. | 1–10% [6] [23] |

| Formamide | Similar to DMSO, it weakens hydrogen bonding, increasing stringency. | 1.25–10% [7] [23] |

| Betaine | Equalizes the stability of AT and GC base pairs, aiding in the uniform melting of GC-rich templates. | 0.5 M to 2.5 M [6] [23] |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Binds to inhibitors that may be present in the template preparation (e.g., from blood, plants). | 10–100 µg/mL (∼400 ng/µL) [6] [23] |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for PCR Setup

A meticulous and systematic approach to setting up a PCR reaction is fundamental to achieving high efficiency and reproducibility.

- Design and Prepare Primers: Primers should be 15–30 nucleotides long with a GC content of 40–60%. The melting temperatures (Tm) for both primers should be similar (within 5°C), ideally between 52–58°C. Avoid complementarity at the 3' ends to prevent primer-dimer formation [6] [23]. Use reputable software for design.

- Prepare a Master Mix: When setting up multiple reactions, combine all common reagents (water, buffer, dNTPs, MgCl₂, DNA polymerase) into a single Master Mix. This ensures consistency and reduces pipetting errors. Prepare a mix for n+1 reactions to account for pipetting loss [6] [23].

- Aliquot the Master Mix: Dispense the appropriate volume of Master Mix into each PCR tube.

- Add Template and Primers: Add the specific DNA template and primers to their respective tubes. For a negative control, add sterile water instead of template DNA.

- Mix Thoroughly: Gently mix the reaction by pipetting up and down. Avoid introducing bubbles.

- Begin Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a pre-heated thermal cycler and start the programmed protocol.

Diagram 1: PCR Setup Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PCR and RT-PCR [7] [24] [25]

| Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerases | Q5 (NEB), Phusion (NEB) [24] | Provides low error rates for cloning, sequencing, and mutagenesis. |

| Hot-Start Polymerases | OneTaq Hot Start (NEB), Platinum (Thermo Fisher) [7] [24] | Prevents non-specific amplification at room temperature, improving yield and specificity. |

| Reverse Transcriptases | SuperScript II (Thermo Fisher) [26] | Creates complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates for RT-PCR. |

| PCR Enhancers | GC Enhancer (Thermo Fisher), DMSO, Betaine [7] [23] | Aids in the amplification of difficult templates like GC-rich sequences. |

| Cleanup Kits | Monarch PCR & DNA Cleanup Kit (NEB) [24] | Purifies PCR products or template DNA to remove salts, enzymes, and other inhibitors. |

| DNA Repair Mix | PreCR Repair Mix (NEB) [24] | Repairs damaged DNA templates prior to PCR to improve amplification success. |

FAQ: Special Considerations for RT-PCR Efficiency

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) introduces additional complexity, as it involves converting RNA into cDNA before amplification. The quality of the starting RNA is the single most critical factor.

What are the primary causes of low or no amplification in RT-PCR?

- Poor RNA Integrity: Degraded RNA will result in truncated cDNA or no product. Always assess RNA quality by gel electrophoresis or microfluidics to ensure sharp ribosomal RNA bands. Minimize freeze-thaw cycles and use RNase inhibitors [25] [26].

- Genomic DNA (gDNA) Contamination: Can lead to false positives or nonspecific amplification. Treat RNA samples with DNase I and always include a no-RT control (a reaction without reverse transcriptase) to check for gDNA contamination [25] [26].

- Suboptimal Primer Choice: The type of primer used for reverse transcription depends on the RNA template.

- Oligo(dT) primers: Best for synthesizing cDNA from eukaryotic mRNA with poly-A tails.

- Random hexamers: Ideal for degraded RNA, non-polyadenylated RNA (e.g., bacterial), or for generating a comprehensive cDNA pool.

- Gene-specific primers: Provide the highest specificity but only for one target [25].

- Presence of Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors: Residual salts, guanidinium, SDS, or EDTA from RNA purification can inhibit the enzyme. Repurify RNA by ethanol precipitation if inhibition is suspected [25] [26].

How can the reverse transcription process be optimized for difficult RNA targets?

- For RNA with Secondary Structure: Denature the RNA and primers by heating the mixture to 65°C for ~5 minutes before cooling on ice. Use a thermostable reverse transcriptase that allows the reaction to be performed at a higher temperature (e.g., 50°C or more) to melt stable structures [25].

- For Low-Abundance Targets: Use a reverse transcriptase with high sensitivity and efficiency. Increase the amount of input RNA within the linear range of the enzyme, and consider using up to 10% of the first-strand cDNA reaction in the subsequent PCR [25] [26].

Diagram 2: RT-PCR Troubleshooting Guide.

The Critical Impact of Efficiency on Data Accuracy in Gene Expression and Diagnostic Assays

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does "PCR efficiency" mean and why is it critical for data accuracy?

PCR efficiency refers to the rate at which a target DNA sequence is amplified during each cycle of the Polymerase Chain Reaction. An ideal, 100% efficient reaction means the amount of PCR product doubles exactly with every cycle. This efficiency is a cornerstone of accurate quantification, especially in real-time PCR (qPCR) used for gene expression analysis.

Even slight deviations from perfect efficiency can lead to significant quantitative inaccuracies. For instance, if the PCR efficiency drops to 0.90 (90%) instead of 1.0 (100%), the resulting error at a threshold cycle of 25 can be as high as 261%, meaning the calculated expression level could be 3.6-fold less than the actual value [2]. Another study demonstrated that a mere 4% decrease in PCR efficiency could result in a 400% error when using the common cycle-threshold (Ct) quantification method [27]. Maintaining high and consistent PCR efficiency is therefore non-negotiable for reliable diagnostic and research outcomes.

My negative control is clean, but my PCR product appears as a smear on the gel. What should I do?

A smear in the absence of contamination typically indicates overcycling, suboptimal reaction conditions, or poorly designed primers. You can optimize your experiment by [28]:

- Reducing the number of PCR cycles to prevent accumulation of non-specific products and errors.

- Increasing the annealing temperature in increments of 2°C to enhance specificity.

- Reducing the amount of template DNA used in the reaction.

- Redesigning your primers to avoid self-complementarity and ensure specificity to the target.

- Using touchdown PCR or nested PCR to improve amplification specificity.

How can I identify and overcome PCR inhibition in my samples?

PCR inhibitors are substances that co-purify with your nucleic acids and can lead to reduced sensitivity, inefficient amplification, or even false-negative results [28].

- Common Inhibitors: These include heparin, hemoglobin, IgG, polysaccharides, melanin, humic acids, SDS, phenol, ethanol, and guanidinium [4].

- How to Identify Inhibition: In qPCR, you can perform a dilution series of your sample. If the sample contains inhibitors, the CT values between consecutive dilutions will be less than the expected 3.3 cycles (for a 10-fold dilution). A smeared standard curve can also indicate inhibition [4] [27].

- Solutions:

- Further purify your template DNA or RNA using ethanol precipitation, column-based cleanup kits, or phenol-chloroform extraction [7] [4].

- Dilute your template sample to reduce the concentration of the inhibitor [28].

- Use a DNA polymerase with high processivity and tolerance to common inhibitors found in samples like blood, soil, or plant tissues [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting No or Low Amplification

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product | Poor primer design | Verify primer specificity using BLAST; ensure primers are not self-complementary; check for appropriate GC content (40-60%) and a G or C at the 3' end [7] [6]. |

| Incorrect annealing temperature | Perform a temperature gradient PCR; start at 5°C below the calculated Tm of your primers [29]. | |

| Presence of PCR inhibitors | Repurify template DNA using a cleanup kit or ethanol precipitation; use a polymerase tolerant to inhibitors [7] [28]. | |

| Insufficient template quantity or quality | Increase the amount of template; assess DNA integrity by gel electrophoresis; ensure A260/A280 ratio is ~1.8-2.0 [7] [4]. | |

| Suboptimal Mg2+ concentration | Optimize Mg2+ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments; ensure Mg2+ concentration is higher than the total dNTP concentration [7] [29]. | |

| Low Yield | Too few cycles | Increase the number of cycles by 3-5, up to 40 cycles, especially for low-abundance targets [7] [28]. |

| Poor polymerase performance | Use a polymerase with high sensitivity and processivity; ensure the enzyme is active and stored correctly [7]. | |

| Complex template (e.g., high GC%) | Use a PCR additive like DMSO, formamide, or a commercial GC enhancer; increase denaturation temperature [7] [29]. | |

| Short extension time | Increase the extension time, particularly for long amplicons [7] [28]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Non-Specific Amplification and Smearing

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Bands or Smearing | Low annealing temperature | Increase the annealing temperature stepwise by 2°C increments [7] [28]. |

| Excess primer concentration | Optimize primer concentration, typically between 0.1–1 μM; high concentrations promote primer-dimer formation [7]. | |

| Too much template DNA | Reduce the amount of template by 2–5 fold [28]. | |

| High Mg2+ concentration | Lower the Mg2+ concentration to reduce non-specific binding and improve fidelity [7] [29]. | |

| Non-hot-start polymerase | Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent activity at room temperature and suppress primer-dimer formation [7] [29]. | |

| Excessive number of cycles | Reduce the number of PCR cycles to prevent accumulation of non-specific products [7] [28]. |

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Quantitative Inaccuracy in qPCR

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor PCR Efficiency (Slope < -3.6 or > -3.3) | Suboptimal primer/probe design | Redesign primers and probes; perform bioinformatic evaluation to ensure specificity and avoid SNP sites and low-complexity regions [4]. |

| PCR inhibition in samples | Further purify the RNA/DNA template; use an inhibition plot to identify inhibited samples [4] [27]. | |

| Inaccurate pipetting | Use calibrated pipettes; avoid pipetting volumes <5 µl; centrifuge plates before running [4]. | |

| Improper baseline/threshold setting | Use the auto-baseline and auto-CT features of your qPCR software; ensure the threshold is set in the exponential phase of all amplifications [4]. | |

| High Variability Between Replicates | Inconsistent sample pipetting | Check pipette calibration; mix reagents thoroughly before use; ensure homogeneous reagent distribution [7] [4]. |

| Low template concentration | Stochastic variations are inherent at very low copy numbers; increase template amount if possible [4]. | |

| Incorrect quantification using ΔΔCT method | Different amplification efficiencies between target and reference genes | Do not use the ΔΔCT method if efficiencies differ. Prepare standard curves for both genes and use a relative quantification model that accounts for different efficiencies [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining PCR Amplification Efficiency

This protocol is essential for validating any qPCR assay to ensure accurate quantification [4] [2].

- Prepare a Standard Curve: Create a dilution series of your target DNA or cDNA (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000, 1:10,000). A minimum of 5 dilution points is recommended, each run in triplicate.

- Run Real-Time PCR: Amplify the dilution series using your optimized qPCR protocol.

- Analyze the Data: The qPCR software will generate a standard curve by plotting the Log of the starting template quantity against the CT value for each dilution.

- Calculate Efficiency: Determine the slope of the standard curve. Use the following formula to calculate the amplification efficiency (E):

Protocol 2: Systematic PCR Optimization

A robust methodology for setting up and optimizing a conventional PCR experiment [6].

- Primer Design:

- Design primers 15-30 nucleotides long with a GC content of 40-60%.

- Ensure the 3' end ends in a G or C to increase priming efficiency.

- Check that primers are not self-complementary or complementary to each other to avoid hairpins and primer-dimers.

- Calculate the melting temperature (Tm) for both primers; the Tm values should not differ by more than 5°C.

- Reaction Setup:

- Assemble reagents on ice. A typical 50 µl reaction includes:

- 1X PCR Buffer (supplied with polymerase)

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 1.5 mM MgCl₂ (optimize if necessary, see troubleshooting guides)

- 0.1–1 µM of each primer

- 10–1000 ng template DNA

- 0.5–2.5 units of DNA Polymerase

- Nuclease-free water to 50 µl

- Include both negative (no template) and positive controls.

- Assemble reagents on ice. A typical 50 µl reaction includes:

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–98°C for 2–5 minutes.

- Amplification (25–40 cycles):

- Denature: 94–98°C for 15–30 seconds.

- Anneal: 45–72°C for 15–60 seconds (set 3–5°C below primer Tm).

- Extend: 68–72°C for 1 minute per kb of product.

- Final Extension: 68–72°C for 5–10 minutes.

- Analysis: Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

The following workflow outlines the logical steps for diagnosing and resolving common PCR problems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential reagents and materials for troubleshooting and optimizing PCR experiments.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive at room temperature to prevent non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation prior to the first denaturation step, greatly improving specificity [7] [29]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Contains proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity to correct nucleotide misincorporation, resulting in much lower error rates. Essential for cloning and sequencing applications [29]. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, BSA, Betaine) | Co-solvents that help denature complex DNA secondary structures, especially in GC-rich templates. They improve yield and specificity by facilitating primer binding [7] [6]. |

| MgCl₂ / MgSO₄ Solution | Magnesium ions are essential cofactors for DNA polymerase activity. The concentration must be optimized, as it directly affects enzyme activity, specificity, and fidelity [7] [29] [6]. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis. Use balanced, equimolar concentrations to prevent misincorporation of bases, which can lead to mutations [7] [29]. |

| Nucleic Acid Cleanup Kit | For removing PCR inhibitors (e.g., salts, proteins, phenol) from template DNA samples. Crucial for restoring amplification efficiency when working with complex biological samples [7] [28] [4]. |

| TaqMan Probes / SYBR Green I | Fluorescent chemistries for real-time PCR quantification. TaqMan probes offer high specificity, while SYBR Green I is a cost-effective option for well-optimized assays [27]. |

Methodological Mastery: Designing and Executing High-Efficiency PCR and RT-PCR Assays

FAQs on PCR Primer Design

What are the most critical parameters for designing a good PCR primer? The most critical parameters are primer length, melting temperature (Tm), GC content, and the absence of secondary structures. Primers should be 18-30 bases long, have a Tm between 55-65°C, a GC content of 40-60%, and must be screened to avoid self-dimers, hairpins, or cross-dimers with the partner primer [30] [31] [32].

How can I prevent primer-dimer formation? Primer-dimer occurs when primers anneal to each other. To prevent it [30] [33] [31]:

- Design carefully: Use software tools to ensure primers lack complementary sequences, especially at their 3' ends.

- Optimize reaction conditions: Lower primer concentrations and increase annealing temperatures can reduce dimerization.

- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase: This enzyme is inactive until high temperatures are reached, preventing spurious amplification during reaction setup.

Why is my PCR efficiency low, and how is it related to primer design? In quantitative PCR (qPCR), efficiency measures how perfectly the target doubles each cycle. Ideal efficiency is 100%. Low efficiency can result from poor primer design, including primers with inappropriate Tm, secondary structures, or sequences that lead to non-specific binding [1] [3]. These issues prevent the polymerase from working optimally, reducing amplification yield.

What is a GC clamp, and why is it important? A "GC clamp" refers to having a G or C base at the 3' end of the primer. Because G and C bases form stronger hydrogen bonds than A and T, a GC clamp helps stabilize the binding of the primer to the template DNA, increasing priming efficiency and specificity [6] [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: No Amplification or Low Yield

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect Annealing Temperature

- Cause: Poor Primer Specificity or Quality

- Cause: Suboptimal Mg2+ Concentration

Problem 2: Non-Specific Bands or Smearing

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Annealing Temperature is Too Low

- Cause: Primer Concentration is Too High

- Cause: Genomic DNA Contamination

Problem 3: Primer-Dimer Formation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Complementarity at Primers' 3' Ends

- Cause: Overabundant Primers

- Cause: Inefficient Polymerase

Data Presentation: Optimal Primer Design Parameters

The following table summarizes the key quantitative parameters for designing effective primers, synthesized from industry-leading guidelines [30] [31] [6].

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Key Considerations & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18 - 30 nucleotides | Provides a balance between specificity (longer) and binding efficiency (shorter) [31] [32]. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 55°C - 65°C | The Tm for both primers in a pair should be within 2°C - 5°C of each other [31] [6]. |

| GC Content | 40% - 60% | Sequences with <40% GC may be less stable; >60% GC may form stable secondary structures [30] [35]. |

| GC Clamp | G or C at the 3'-end | Strengthens the terminal binding due to stronger hydrogen bonding [6] [32]. |

| 3' End Stability | Avoid >3 G/C in last 5 bases | Prevents mispriming and non-specific amplification at the critical extension point [35]. |

| Amplicon Length | 70 - 150 bp (qPCR)Up to 500 bp (standard PCR) | Shorter amplicons are amplified more efficiently in qPCR. Longer amplicons may require extended extension times [31]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Primer Design and Validation Workflow

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for designing and validating primers before synthesis [35].

- Define Target: Obtain the exact reference sequence (FASTA format) from a trusted database like NCBI. Define the boundaries of the region you wish to amplify.

- Use Design Tool: Input your sequence into a specialized tool like NCBI Primer-BLAST or Primer3.

- Set parameters to the optimal ranges listed in the table above (e.g., product size, Tm).

- Select the appropriate organism for specificity checking.

- Evaluate Candidates: From the list of generated primer pairs, select several candidates that best meet the design criteria.

- Screen for Secondary Structures: Analyze each candidate primer sequence using a tool like the IDT OligoAnalyzer.

- Check for hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers.

- Accept structures with ΔG values weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [31].

- Final Specificity Check: Use the integrated BLAST function in Primer-BLAST to confirm the primer pair will amplify only your intended target and no other regions in the genome.

Protocol 2: Empirical Optimization of Annealing Temperature

Even well-designed primers may require experimental optimization [19] [6].

- Prepare Master Mix: Create a standard PCR master mix containing your template, primers, polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer.

- Set Up Gradient PCR: Aliquot the master mix into PCR tubes and run them in a thermal cycler with a gradient annealing temperature function.

- Set Temperature Range: Program the gradient to test a range from 3-5°C below the calculated lower Tm to 3-5°C above the calculated higher Tm.

- Analyze Results: Run the PCR products on an agarose gel. The correct annealing temperature will yield a single, bright band of the expected size with no smearing or primer-dimer.

Visualization: Primer Design and Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing primers and the primary troubleshooting paths for common experimental failures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and reagents used in PCR primer design and troubleshooting [30] [19] [31].

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme activated only at high temperatures; critical for reducing primer-dimer and non-specific amplification during reaction setup [19] [33]. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis. Unbalanced or degraded dNTPs can cause failed PCR [19] [6]. |

| MgCl2 Solution | A essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Its concentration is a primary variable for reaction optimization [19] [6]. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, BSA, Betaine) | Used to enhance amplification of difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich regions) or to overcome the effects of inhibitors in the reaction [19] [6]. |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool | A free online tool for analyzing Tm, hairpins, self-dimers, and heterodimers of designed primer sequences [31]. |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | A critical tool that combines primer design with a specificity check against genomic databases to ensure primers are unique to the target [35]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Used to prepare all reagent stocks and reactions; prevents degradation of primers and template by environmental nucleases [34]. |

Core Concepts and Strategic Importance

What are the primary challenges when designing primers for regions with high sequence homology or SNPs?

Designing primers for regions with high sequence homology or containing Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) presents unique challenges that can compromise assay specificity and performance. Homologous sequences, which are similar DNA segments found elsewhere in the genome, can serve as unintended primer binding sites, leading to non-specific amplification and false positive results. Similarly, SNPs within primer binding sites can act as mismatches that reduce amplification efficiency or, in the case of allele-specific PCR, prevent the detection of specific variants.

The core challenges include:

- Mispriming in Homologous Regions: Primers may bind to non-target sequences with high similarity, co-amplifying homologous genes or pseudogenes. This is particularly problematic in gene families with conserved regions or in polyploid organisms [36].

- Allele Dropout from SNP Interference: Unidentified SNPs in primer binding sites, especially near the 3' end, can cause preferential amplification of one allele over another, leading to genotyping errors and inaccurate results in quantitative applications [37] [36].

- Reduced Amplification Efficiency: Template structures influenced by flanking sequences and localized GC content significantly impact PCR efficiency. This is critical in quantitative PCR (qPCR) where efficiency values directly influence gene expression calculations [38].

How do these factors impact PCR amplification efficiency and quantification accuracy?

The presence of homologous sequences or SNPs directly impacts key PCR performance metrics, particularly in quantitative applications. Amplification efficiency (E), defined as the fraction of target molecules copied per PCR cycle, is highly dependent on assay design and template characteristics [38]. Inefficient reactions (E < 90%) lead to substantial underestimation or overestimation of target concentration. In qPCR, a 5% difference in efficiency can result in greater than 400% error in calculated fold-change differences when comparing samples with large expression variations [39]. Furthermore, homologous sequences can cause overestimation of starting template quantity due to non-specific amplification, while SNP-induced mismatches can create inefficient reactions that fail to reach threshold fluorescence, thereby underestimating true target concentration.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: In Silico Primer Design for Specific Amplification

This protocol ensures primer specificity while accounting for homologous sequences and known SNP positions.

Step 1: Sequence Retrieval and Analysis

- Obtain the complete target sequence with at least 50-100 nucleotides flanking the region of interest [36].

- Identify known SNP positions using databases like dbSNP and note their locations relative to your target.

- Perform a BLAST search to identify homologous sequences and conserved domains that might cause mispriming.

Step 2: Primer Design with Specificity Parameters

- Design primers 15-30 nucleotides long with optimal GC content between 40-60% [6].

- Position the 3' end of allele-specific primers directly at the SNP site for genotyping assays [36].

- Avoid primer placement in regions with high homology to non-target sequences.

- Ensure balanced melting temperatures (Tm) between 52-65°C for both primers, with not more than 5°C difference [6].

- Incorporate unique "anchor" bases near polymorphic sites to enhance selectivity in homologous regions [36].

Step 3: Specificity Verification Using Primer-BLAST

- Use the NCBI Primer-BLAST tool to verify target specificity [37] [6].

- Select appropriate databases for your organism and enable specific search parameters:

- Check "Primer pair specificity checking"

- Select "Show results with at least mismatches to primer(s)" to detect potential cross-hybridization

- For SNP-aware design, use the "Exclude primers binding to SNP" option or intentionally place primers over SNPs for allele-specific design [37].

- Analyze results to ensure primers only hit the intended target sequence.

Step 4: Efficiency Prediction

- Use online tools like pcrEfficiency to predict amplification efficiency before wet-lab experiments [38].

- Input primer sequences and template to obtain efficiency estimates based on amplicon characteristics.

Protocol 2: SNP Genotyping Using Competitive Allele-Specific PCR

This protocol describes the PACE (PCR Allele Competitive Extension) system for reliable SNP and Indel detection [36].

Step 1: Primer Design for Allele-Specific PCR

- Design two allele-specific forward primers that differ only at their 3' terminal nucleotide corresponding to the SNP variant.

- Design one common reverse primer located downstream of the polymorphism.

- Add universal tail sequences to the 5' ends of allele-specific primers for fluorescence detection.

Step 2: Reaction Setup

- Prepare a master mix containing:

- 1X PACE Master Mix (contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and universal fluorescent reporters)

- 0.5-1 μM of each allele-specific forward primer

- 0.5-1 μM of common reverse primer

- 10-100 ng genomic DNA template

- Aliquot into PCR tubes or plates.

Step 3: Thermal Cycling

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5-10 minutes

- 35-40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60-65°C for 30-60 seconds (optimize based on primer Tm)

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

Step 4: Fluorescence Detection and Genotype Calling

- Read endpoint fluorescence using a plate reader or real-time PCR instrument.

- For homozygous samples, only one allele-specific primer will amplify, producing a single fluorescent signal.

- For heterozygous samples, both primers will amplify, producing a mixed fluorescent signal.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for SNP Genotyping Assays

| Reagent | Function | Optimal Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Allele-Specific Primers | Discriminate between SNP variants | 0.05-1 μM [40] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification with minimal errors | 0.5-2.5 units/50 μL reaction [6] |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for DNA synthesis | 200 μM each [6] |

| Mg²⁺ Solution | Cofactor for DNA polymerase activity | 1.5-4.0 mM (optimize) [6] |

| Fluorescent Reporting System | Detection of allele-specific amplification | As per manufacturer |

Figure 1: Workflow for robust SNP genotyping assay design and validation

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How can I prevent amplification of homologous sequences when my gene belongs to a conserved gene family? A: To prevent amplification of homologous sequences: 1) Use bioinformatics tools like Primer-BLAST to identify unique regions in your target gene that have minimal similarity to other family members [37]; 2) Position primers across exon-exon junctions when working with cDNA (this eliminates amplification of genomic DNA and often targets more variable regions) [37]; 3) Incorporate deliberate mismatches near the 3' end to destabilize binding to non-target homologs; 4) Increase annealing temperature in increments of 2°C to enhance stringency [41].

Q: What steps can I take when my SNP genotyping assay shows inconsistent clustering or poor allele discrimination? A: Poor allele discrimination in SNP genotyping often results from suboptimal primer design or reaction conditions. First, verify that the 3' end of your allele-specific primers corresponds exactly to the SNP position with the discriminatory base at the ultimate position. Second, optimize Mg²⁺ concentration (test 0.2-1 mM increments) and annealing temperature (use gradient PCR) [40]. Third, ensure primer quality by ordering HPLC-purified oligonucleotides and preparing fresh dilutions. Finally, include known positive controls for all genotypes to validate assay performance.

Q: How do I accurately determine PCR efficiency for my assay, and why do I get efficiencies above 100%? A: PCR efficiency should be determined using a standard curve with serial dilutions (minimum 3-4 replicates per concentration) across at least 5 orders of magnitude [39]. Use the formula: Efficiency = [10^(-1/slope)] - 1. Efficiencies above 100% often indicate technical issues such as: 1) PCR inhibition in concentrated samples causing deviation from linearity; 2) inaccurate pipetting during dilution series preparation; 3) template degradation; or 4) presence of contaminants. To improve accuracy, use larger volumes (>2 μL) when preparing serial dilutions to minimize sampling error, and ensure the template is pure and intact [39].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

Table 2: Troubleshooting PCR Specificity Issues

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple non-specific bands | Homology to related sequences | Increase annealing temperature 2-5°C; Use touchdown PCR; Redesign primers to target unique regions [41] |

| No amplification product | SNP in primer binding site preventing extension | Verify no known SNPs in primer sites; Redesign primers avoiding polymorphic regions; Lower annealing temperature [37] [40] |

| Smearing or high background | Mispriming in homologous regions | Reduce template amount (2-5 fold); Increase annealing temperature; Use hot-start DNA polymerase [41] |

| Inconsistent genotyping results | Poor allele-specific primer discrimination | Verify 3' end match to SNP; Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration; Use fresh primer aliquots [36] |

| Low PCR efficiency (<90%) | Secondary structures or suboptimal primer design | Redesign primers with balanced Tm; Use additives like DMSO (1-5%) or Betaine (0.5-2.5 M) for GC-rich templates [38] [6] |

Scenario: Failed Amplification Due to Unidentified SNP in Primer Binding Site

Problem: After apparently successful in silico design, a PCR reaction fails to produce any amplification product despite optimization of standard parameters.

Investigation:

- Verify sequence accuracy of the template source and check for updated genome annotations

- Use databases like dbSNP to identify potential polymorphisms within primer binding sites

- Test primers on control templates with known sequences

Solution:

- Redesign primers to avoid polymorphic regions, ensuring at least 50 bp of high-quality sequence information flanking the SNP [36]

- If avoiding the SNP is impossible, position it in the 5' region of the primer rather than the critical 3' end

- For genotyping applications, intentionally place the SNP at the 3' end but design separate allele-specific primers

- Include mismatch-tolerant polymerases or buffers if working with diverse templates containing unknown SNPs

Figure 2: Systematic troubleshooting pathway for PCR specificity issues

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Advanced Primer Design

| Tool/Reagent | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | Target-specific primer design | Combines Primer3 with BLAST to ensure specificity; allows SNP exclusion [37] |

| pcrEfficiency Web Tool | Efficiency prediction before testing | Predicts PCR efficiency based on amplicon length, GC content, and primer parameters [38] |

| PACE Genotyping System | Allele-specific SNP detection | Competitive allele-specific PCR with universal fluorescent reporting; flexible multiplexing [36] |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerases | Specificity enhancement | Prevents non-specific amplification during reaction setup; improves yield of desired product [7] [40] |

| Proofreading Polymerases | High-fidelity applications | Reduces misincorporation errors; essential for cloning and sequencing (e.g., Q5, Phusion) [40] |

| PCR Enhancers/Additives | Challenging templates | DMSO, formamide, or Betaine help denature GC-rich templates and resolve secondary structures [6] |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Why Should I Use DOE Instead of Traditional Methods for Probe Optimization?

Answer: Using a Design of Experiments (DOE) approach for probe optimization, rather than a One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) method, provides significant advantages in efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and the quality of your results.

- Efficiency and Reduced Experimental Burden: DOE allows you to test multiple factors and their interactions simultaneously. A study on mediator probe (MP) design for real-time PCR demonstrated that DOE required a maximum of 180 individual reactions, whereas an OFAT approach would have needed 320 reactions [42] [43]. This represents a substantial reduction in time and laboratory resources.

- Identification of Critical Interactions: Biological systems are complex, and factors often interact in non-independent ways. OFAT approaches cannot detect these interactions, which can lead to incorrect conclusions. DOE is specifically designed to quantify how factors influence one another, helping you find a true optimum instead of a local maximum [44] [45]. For instance, in MP PCR optimization, DOE revealed that the dimer stability between the mediator and the universal reporter had the greatest influence on assay performance, increasing PCR efficiency by up to 10% [43].

- Avoiding Suboptimal Results: Because OFAT ignores interactions, the final combination of variable set points it identifies is often suboptimal. The order in which you optimize variables in OFAT can change the final outcome, a pitfall that DOE avoids by exploring the multi-factor design space comprehensively [45].

How Do I Get Started with a DOE Approach for My Assay?

Answer: Implementing a DOE-based optimization involves a structured process from goal definition to experimental execution. The workflow below outlines the key stages:

Step 1: Define Your Goal and Target Value Clearly define what you want to optimize. The goal should be specific and measurable. For a PCR assay, this could be achieving a detection limit of 10-100 target copies per reaction [43]. To monitor progress, you can create a single "target value" that combines several performance characteristics (e.g., PCR efficiency, R², and Cq value) into one quantifiable metric [43].

Step 2: Select Input Factors and Their Levels Choose the key factors you believe will influence your assay. In probe optimization, critical factors often include [42] [43]:

- Dimer Stability (ΔG): The Gibbs free energy of dimer formation between the probe and its target or a universal reporter.

- Primer-Probe Distance: The distance between the primer's annealing site and the probe's cleavage site.

- Probe Concentration.

For each factor, select a minimum of two "levels" (i.e., specific values to test). For example, you might test dimer stability (ΔG) at two levels: a high-stability value (e.g., -8 kcal/mol) and a low-stability value (e.g., -4 kcal/mol) [43].

Step 3: Execute the DOE and Analyze Results Using a statistical software package, generate an experimental matrix—a list of all the different factor-level combinations that need to be tested. After running the experiments and collecting data on your target value, the software will perform an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine which factors and interactions have a statistically significant effect. This allows you to build a model that predicts the optimal probe design configuration [43] [45].

My PCR Efficiency is Low Even After Probe Redesign. What Else Should I Check?

Answer: Low amplification efficiency can stem from issues beyond probe design. If you have optimized your probe using DOE and still face problems, investigate these common areas:

- Primer Design and Concentration: Verify that your primers are specific, do not form primer-dimers (particularly with a stable 3'-end ΔG ≥ -2.0 kcal/mol), and are used at an optimal concentration, typically between 200-400 nM for SYBR Green assays [46]. Problematic primer design is a leading cause of poor specificity and yield [7].

- Template Quality and Quantity: Assess the integrity and purity of your DNA or RNA template. Degraded DNA or contaminants like phenol, EDTA, or salts can inhibit the reaction. Re-purify your template if necessary [7] [25].

- Mg²⁺ Concentration: Magnesium is a essential cofactor for DNA polymerase. Insufficient Mg²⁺ can drastically reduce PCR efficiency. Optimize the Mg²⁺ concentration for your specific primer-template system [7].

- Thermal Cycler Conditions: Suboptimal annealing temperature is a frequent culprit. Use a gradient thermal cycler to determine the optimal annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments, typically 3-5°C below the primer Tm [7] [46].

How Can I Improve the Detection Limit and Reproducibility of My qPCR Assay?

Answer: To enhance sensitivity and reproducibility, focus on the following:

- Use a Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: This minimizes non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation at low temperatures, which is crucial for robust detection of low-copy-number targets [7].

- Thoroughly Optimize Primer and Probe Concentrations: As part of your DOE screening, include primer and probe concentration as key factors. The optimal balance minimizes Cq values and variation between replicates while ensuring the no-template control (NTC) remains negative [46].

- Ensure Reaction Homogeneity: Mix all reagent stocks and prepared reactions thoroughly to eliminate density gradients that form during storage and setup, which can cause well-to-well variation [7].

- Validate with a Standard Curve: A well-optimized assay will have a standard curve with a slope corresponding to an efficiency between 90-105% (a slope of -3.6 to -3.1) and an R² value >0.985 [46]. This confirms both sensitivity and linearity over your desired dynamic range.

Experimental Protocols and Data

Detailed Methodology: DOE-Based Probe Optimization

The following protocol is adapted from studies on optimizing mediator probes (MP) in real-time PCR [43].

Definition of Optimization Goal

- Objective: Achieve a detection limit of 3-14 target copies per 10 µL reaction for influenza B virus (InfB) RNA [43].

- Target Value Calculation: A single target value (TV) is calculated from multiple performance characteristics to streamline optimization: TV = a×R² + b×PCR efficiency + c×signal increase + d×Cq value at 10⁴ copies/reaction The coefficients (a-d) are weighting factors determined based on the mean values of the performance characteristics from initial screening experiments [43].

Input Factor Screening

- Selected Factors:

- Factor A: Dimer stability (ΔG) between the mediator probe (MP) and the target sequence (InfB).

- Factor B: Dimer stability (ΔG) between the mediator probe (MP) and the universal reporter (UR).

- Factor C: Distance between the primer and the mediator probe's cleavage site.

- Experimental Design: A screening design (e.g., a fractional factorial design) is used to test these three factors at multiple levels. The study cited used nine different MP designs to maximize information from the experiments [42] [43].

Experimental Procedure

- Primer and Probe Design: Design several mediator probe variants that cover the desired ranges for the three input factors (A, B, and C).

- Template Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of the target RNA (e.g., InfB RNA) covering a range from below the desired detection limit to a high copy number (e.g., 10 to 10⁶ copies/reaction).

- RT-MP PCR Setup: Perform reverse transcription and MP PCR reactions using a one-step kit. Each reaction should contain:

- The specified target RNA.

- Primers at a constant, pre-optimized concentration.

- One of the nine MP variants from the experimental design.

- The universal reporter (UR).

- Master mix, enzymes, and nuclease-free water.

- Run Real-Time PCR: Amplify the samples on a real-time PCR instrument using the recommended temperature profile for hydrolysis probes.

- Data Collection: Record the Cq values, fluorescence signal increase, and other relevant metrics for each reaction. Calculate the target value for each MP design.

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from relevant DOE studies in PCR optimization.

Table 1: Summary of Quantitative Data from DOE Optimization Studies

| Study Focus | Key Factors Optimized | DOE Efficiency (Number of Reactions) | OFAT Equivalent (Number of Reactions) | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR Probe Design [42] [43] | Probe-Target ΔG, Probe-Reporter ΔG, Primer-Probe Distance | 180 | 320 | Detection limit of 3-14 copies/reaction; PCR efficiency increased by up to 10%. |

| Multiplex RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 [12] | Primer/Probe Concentrations (0.2 µM selected) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Achieved 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity; detection limit of 10 copies/reaction in a triplex format. |