Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Delivery Systems for Nucleic Acid Drugs: A Strategic Evaluation for Next-Generation Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of targeted and non-targeted nucleic acid drug delivery systems for researchers and drug development professionals.

Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Delivery Systems for Nucleic Acid Drugs: A Strategic Evaluation for Next-Generation Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of targeted and non-targeted nucleic acid drug delivery systems for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of nucleic acid therapeutics—including ASOs, siRNAs, and mRNA—and their delivery challenges. The content systematically compares the methodologies, applications, and optimization strategies for viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, polymer-based systems, and ligand-conjugated platforms. By analyzing clinical validation data and comparative performance metrics, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and engineering delivery systems to overcome biological barriers and advance the clinical translation of nucleic acid drugs.

Nucleic Acid Therapeutics and the Imperative for Advanced Delivery

Nucleic acid drugs represent a revolutionary class of therapeutics that use engineered sequences of DNA, RNA, or synthetic analogs to treat diseases by targeting their underlying genetic causes rather than just the symptoms [1]. This category has expanded significantly beyond early concepts to include a diverse arsenal of modalities including antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), messenger RNA (mRNA), and the CRISPR-Cas gene editing system [2] [3]. Unlike traditional small molecule drugs that primarily target proteins, nucleic acid therapeutics can theoretically target any gene by leveraging the principle of complementary base pairing, making them particularly valuable for addressing previously "undruggable" targets [1]. The field has gained substantial momentum in recent years, with the global nucleic acid therapeutics market projected to grow from $6.01 billion in 2024 to $12.24 billion by 2029, representing a compound annual growth rate of 15.2% [4].

The development of these therapeutics is inseparable from major discoveries in molecular biology, from the initial conceptualization of antisense technology in 1978 to the Nobel Prize-winning discovery of RNA interference in 1998 and the more recent development of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic notably accelerated the field, with mRNA vaccines demonstrating the tremendous potential of nucleic acid therapeutics on a global scale [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the major nucleic acid drug modalities, with particular focus on their applications within targeted versus non-targeted delivery system research.

Comparative Analysis of Major Nucleic Acid Drug Modalities

Fundamental Characteristics and Mechanisms

Table 1: Comparison of Key Nucleic Acid Drug Modalities

| Characteristic | ASOs | siRNAs | mRNA | CRISPR-Cas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Type | Single-stranded oligonucleotides (18-30 nt) [1] | Double-stranded RNA (20-25 bp) [5] | Single-stranded RNA (hundreds to thousands of nt) [5] | RNA-protein complex or mRNA + gRNA [6] |

| Primary Mechanism | RNase H1-mediated degradation or steric hindrance [1] | RNAi pathway: RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage [7] | Protein replacement: in vivo protein production [2] | Gene editing: DNA cleavage and repair [8] |

| Cellular Target | Nucleus/Cytosol [6] | Cytosol [6] | Cytosol [6] | Nucleus [6] |

| Therapeutic Effect | Transient knockdown [8] | Transient knockdown [8] | Transient expression [2] | Permanent knockout or knock-in [8] |

| Key Advantages | Multiple mechanisms; splicing modulation [1] | High specificity; multi-targeting potential [9] | Non-integrating; broad applicability [2] | Permanent correction; versatile editing [2] |

| Key Challenges | Off-target effects; delivery limitations [7] | Off-target effects; RISC saturation risk [7] | Immunogenicity; instability [2] | Off-target edits; ethical considerations [2] |

Key Differentiating Factors for Research Applications

When selecting a nucleic acid modality for research or therapeutic development, several critical factors must be considered. The choice between knockdown versus knockout is fundamental: while ASOs and siRNAs reduce gene expression (knockdown), CRISPR generates permanent genetic modifications (knockout) [8]. This makes CRISPR ideal for studying essential genes or creating stable cell lines, while RNAi methods are better suited for studying genes where complete knockout would be lethal [8].

Specificity and off-target effects represent another crucial consideration. RNAi methods, particularly siRNAs, can suffer from significant off-target effects due to partial complementarity with non-target mRNAs [8] [7]. Although CRISPR initially had sequence-specific off-target effects, advanced guide RNA design and chemically modified sgRNAs have substantially reduced these concerns, making CRISPR generally more specific than RNAi for most applications [8].

The duration of effect also varies significantly: ASOs, siRNAs, and mRNA therapeutics provide transient effects (days to weeks), making them suitable for acute conditions or vaccines [8] [2]. In contrast, CRISPR-Cas can create permanent genetic changes, offering potential one-time treatments for genetic disorders but raising safety concerns about irreversible edits [2].

Delivery Systems: Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Approaches

Delivery Challenges and Pharmacological Barriers

All nucleic acid therapeutics face significant delivery challenges that must be addressed for successful research and clinical application. As negatively charged macromolecules, nucleic acids cannot passively diffuse across cellular membranes and are highly vulnerable to degradation by nucleases in the bloodstream [6] [2]. Furthermore, they are rapidly cleared by the kidneys and can trigger immune responses [2]. Perhaps the most significant barrier is endosomal entrapment: after cellular uptake, nucleic acids often become trapped in endosomes and are subsequently degraded in lysosomes, never reaching their intended subcellular targets [6] [2].

Different nucleic acid modalities have distinct subcellular destination requirements that further complicate delivery. For instance, siRNA and mRNA function in the cytosol, while ASOs and CRISPR-Cas need to reach the nucleus to access genomic DNA or pre-mRNA [6]. These varying requirements necessitate carriers with different functional domains optimized for specific cargo types and target cells [6].

Targeted Delivery Systems

Targeted delivery systems employ specific ligands that recognize and bind to receptors on particular cell types, enabling precision targeting of therapeutic nucleic acids.

GalNAc Conjugates: N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) conjugates represent one of the most successful targeted delivery approaches, specifically targeting the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) highly expressed on hepatocytes [5]. This technology has revolutionized liver-targeted siRNA therapeutics, with advantages including low immunogenicity, improved stability, and strong specific targeting [5]. However, its application is limited primarily to liver diseases, with stronger targeting of normal hepatocytes than diseased cells potentially limiting efficacy in some hepatic disorders [5].

Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs): These conjugates utilize monoclonal antibodies that bind specifically to receptors on target cells, enabling rapid and precise delivery [5]. AOCs offer strong targeting capabilities with low toxicity but face challenges including complex pharmacokinetics, short duration of efficacy, and degradation of the monoclonal antibody after cellular internalization [5].

Peptide-Based Targeted Carriers: Sequence-defined peptide carriers can be designed with specific targeting ligands to enable cell-specific delivery [6]. These synthetic peptides offer precise control over chemical structure and functionality, allowing researchers to incorporate various functional domains including nucleic acid binding regions, endosomal escape enhancers, and tissue-specific targeting moieties [6].

Non-Targeted Delivery Systems

Non-targeted systems rely on physicochemical properties and passive accumulation mechanisms for nucleic acid delivery.

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): LNPs have emerged as the leading non-viral delivery platform, particularly following their successful use in COVID-19 mRNA vaccines [2] [5]. These systems encapsulate nucleic acids within lipid bilayers, protecting them from degradation and facilitating cellular uptake through endocytosis [5]. LNPs can be modified with PEG lipids to enhance stability and circulation time, though this can sometimes lead to cytotoxicity concerns [5]. Their primary advantages include strong encapsulation efficiency, ease of preparation, and biodegradability, though they can suffer from significant off-target effects in non-liver tissues without additional targeting modifications [5].

Cationic Polymers: Cationic polymers, including sequence-defined peptides, form polyplexes with nucleic acids through electrostatic interactions [6]. Linear, dendritic, and hyperbranched poly(L)lysine (PLL) structures have been extensively studied, with branching generally beneficial for transfection efficiency though sometimes accompanied by increased cytotoxicity [6]. Incorporation of histidine residues enhances endosomal buffering and escape capacity, while cysteine residues enable disulfide cross-linking for improved polyplex stability [6].

Viral Vectors: Viral vectors, particularly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), remain important delivery vehicles for nucleic acid therapeutics, especially for CRISPR-based therapies [5]. They offer efficient transduction and long-term expression but face challenges including immunogenicity, limited cargo capacity, and potential insertional mutagenesis concerns [6] [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Delivery Systems

| Delivery System | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GalNAc Conjugates | ASGPR receptor-mediated endocytosis [5] | High specificity to hepatocytes; low immunogenicity; clinical validation [5] | Limited to liver targeting; potentially reduced uptake in diseased hepatocytes [5] | Liver-specific diseases (e.g., hATTR amyloidosis, hepatitis) [1] |

| Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs) | Antibody-receptor binding and internalization [5] | High specificity; adaptable to various cell types; potential for immune cell targeting [5] | Complex manufacturing; limited payload; potential immunogenicity [5] | Oncology; targeted delivery to specific cell populations [5] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Endocytosis; passive targeting [5] | Proven clinical success; adaptable to various nucleic acid types; scalable production [2] [5] | Primarily hepatic accumulation without targeting; potential cytotoxicity with PEG [5] | Vaccines; systemic delivery when broad tissue distribution is acceptable [2] |

| Cationic Polymers | Electrostatic complexation; endosomal buffering [6] | Tunable properties; potential for biodegradability; enhanced endosomal escape [6] | Variable cytotoxicity; complex structure-activity relationships [6] | Local delivery; in vitro research; customizable carrier design [6] |

| Viral Vectors (AAV) | Viral transduction; nuclear delivery [5] | High transduction efficiency; long-lasting expression; tissue-specific serotypes [5] | Immunogenicity; limited cargo capacity; pre-existing immunity [6] [5] | Gene therapy requiring sustained expression; hard-to-transfect cells [2] |

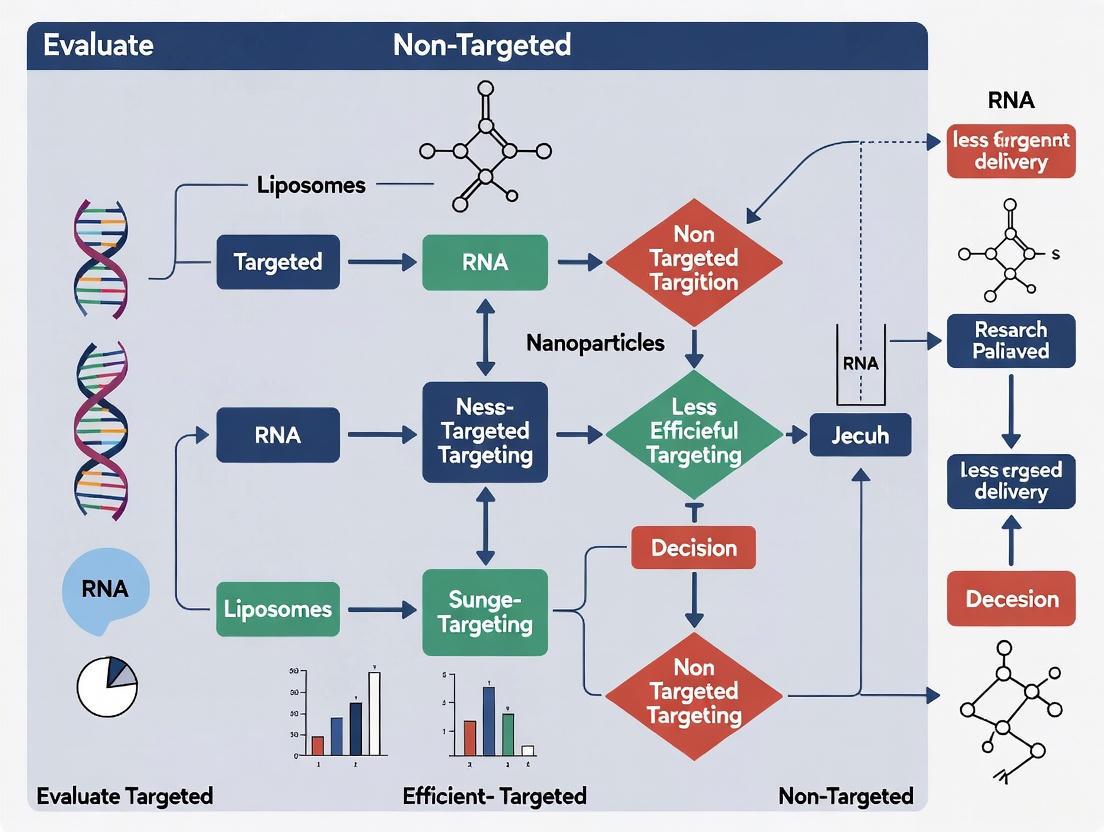

Nucleic Acid Delivery Pathways Comparison

Experimental Protocols for Delivery System Evaluation

In Vitro Assessment of Delivery Efficiency

Protocol 1: Quantitative Cellular Uptake and Internalization Analysis

Materials Required:

- Fluorescently labeled nucleic acids (e.g., Cy3-labeled siRNA, FAM-labeled ASO)

- Candidate delivery systems (LNPs, polyplexes, conjugates)

- Target cell lines with relevant receptor expression

- Flow cytometer or confocal microscopy with quantitative image analysis software

- Early endosome marker (e.g., EEA1 antibody) for subcellular localization

Methodology:

- Prepare nucleic acid-loaded delivery systems at optimal N:P ratios (for cationic carriers) or lipid:nucleic acid ratios (for LNPs) [6].

- Treat target cells with formulated complexes at predetermined concentrations (typically 10-200 nM nucleic acid concentration).

- Incubate for 2-24 hours depending on the application and internalization kinetics.

- For flow cytometry: Harvest cells, wash with cold PBS to remove surface-bound complexes, and analyze fluorescence intensity to quantify internalization [6].

- For confocal microscopy: Fix cells, stain with endosomal/lysosomal markers, and perform colocalization analysis to determine endosomal escape efficiency [6].

- Include appropriate controls: naked nucleic acids, free dye, and untreated cells.

Protocol 2: Functional Gene Silencing/Expression Efficiency

Materials Required:

- Reporter system (e.g., luciferase-expressing cells, GFP knockdown models)

- qRT-PCR equipment and reagents for target mRNA quantification

- Western blot apparatus for protein-level analysis

- Cell viability assay kits (MTT, CCK-8, or similar)

Methodology:

- Establish baseline target gene expression in chosen cell model.

- Treat cells with nucleic acid delivery systems targeting the gene of interest.

- For knockdown studies (siRNA, ASO): Incubate 48-72 hours, then harvest for mRNA and protein analysis [8].

- For expression studies (mRNA): Incubate 24-48 hours, then assess protein production via ELISA, western blot, or functional assay [2].

- For CRISPR editing: Extend incubation to 72-96 hours to allow for protein degradation and editing manifestation, then analyze editing efficiency via T7E1 assay, ICE analysis, or sequencing [8].

- Normalize results to control treatments and include appropriate positive and negative controls.

In Vivo Biodistribution and Efficacy Studies

Protocol 3: Biodistribution Analysis Using Radiolabeled or Fluorescent Probes

Materials Required:

- Nucleic acids labeled with near-infrared dyes (Cy5.5, DIR) or radionuclides (⁹⁹mTc, ¹²⁵I)

- In vivo imaging system (IVIS) or microPET/CT scanner

- Tissue homogenization equipment

- Delivery systems formulated with labeled nucleic acids

Methodology:

- Formulate delivery systems incorporating traceable nucleic acids.

- Administer to animal models via relevant route (IV, SC, etc.) at therapeutically appropriate doses.

- Perform time-course imaging at predetermined intervals (1, 4, 24, 48 hours post-injection) to track whole-body distribution [6].

- Euthanize animals at endpoint, collect and image tissues (liver, spleen, kidney, target organs).

- Quantify nucleic acid accumulation in tissues via fluorescence measurement, gamma counting, or qPCR analysis of recovered nucleic acids.

- Process tissues for histological analysis to determine cellular localization within organs.

Protocol 4: In Vivo Therapeutic Efficacy Assessment

Materials Required:

- Disease-relevant animal models (transgenic, xenograft, infection models)

- Delivery systems containing therapeutic nucleic acids

- Disease-specific biomarkers for efficacy evaluation

- Physiological monitoring equipment

Methodology:

- Randomize animals into treatment groups (n=5-8 per group minimum).

- Administer nucleic acid formulations at predetermined dosage schedules.

- Monitor disease progression through appropriate parameters (tumor volume, biomarker levels, behavioral assessments, survival).

- Collect tissues at endpoint for molecular analysis (target reduction, editing efficiency, protein expression).

- Include control groups: untreated, empty delivery system, and appropriate benchmark therapeutics.

- Perform statistical analysis to determine significance of therapeutic effects.

Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Delivery Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nucleic Acid Delivery System Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Modification Reagents | Phosphorothioate backbone [1], 2'-O-methyl [1], 2'-fluoro [5], N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) [5], Pseudouridine (Ψ) [2] | Enhance stability, reduce immunogenicity, enable targeted delivery | Balance between stability improvement and maintenance of biological activity [2] |

| Lipid Nanoparticle Components | Ionizable lipids, PEG-lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol [2] [5] | Formulate protective nucleic acid carriers for in vivo delivery | Optimize ratios for efficiency vs. cytotoxicity; PEG content affects pharmacokinetics [5] |

| Cationic Polymers | Poly(L)lysine (PLL) dendrimers [6], Histidine-Lysine (HK) peptides [6], PEI, sequence-defined carriers [6] | Nucleic acid complexation and endosomal escape enhancement | Molecular weight and branching affect efficiency and toxicity; incorporate buffering domains [6] |

| Targeting Ligands | GalNAc [5], Transferrin, Antibodies [5], Cell-penetrating peptides [6], Aptamers [1] | Cell-specific delivery for enhanced potency and reduced off-target effects | Consider receptor density, internalization efficiency, and ligand orientation [5] |

| Analytical Tools | Dynamic light scattering [10], ELISA for protein expression [2], qRT-PCR [8], NGS for off-target analysis [8] [10], Flow cytometry [6] | Characterize delivery systems and assess biological outcomes | Implement multiple orthogonal methods for comprehensive characterization [10] |

The field of nucleic acid therapeutics has evolved from theoretical concept to clinical reality, with multiple modalities now available to researchers and clinicians. Each modality—ASOs, siRNAs, mRNA, and CRISPR-Cas—offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suited for different therapeutic applications. The critical challenge across all platforms remains efficient delivery to target tissues and cells, with both targeted and non-targeted approaches showing promise for different applications.

Looking forward, several key trends are shaping the future of nucleic acid drug development. Integration of artificial intelligence in nucleic acid design and delivery system optimization is accelerating the development process, with AI algorithms capable of predicting optimal sequences, chemical modifications, and compatible delivery systems [4] [9]. Advanced chemical modification strategies continue to emerge, enhancing stability, reducing immunogenicity, and improving the pharmacokinetic profiles of nucleic acid therapeutics [2] [1]. The expansion of delivery capabilities beyond the liver represents a critical frontier, with ongoing research focused on overcoming biological barriers to enable targeting of the central nervous system, solid tumors, and other challenging tissues [6] [10].

The growing pipeline of nucleic acid therapeutics in clinical trials—with the small nucleic acid drug market projected to reach $33.28 billion by 2034—underscores the tremendous potential of this field [9]. As delivery technologies continue to advance, nucleic acid drugs are poised to address an increasingly broad range of genetic, infectious, and chronic diseases, ultimately fulfilling their promise as a transformative modality in modern medicine.

The therapeutic potential of nucleic acid drugs (NADs), including siRNA, mRNA, and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), has transformed modern medicine by enabling targeted intervention at the genetic level [2]. These modalities can silence harmful genes, replace defective proteins, and potentially cure genetic disorders at their source [11] [2]. However, their clinical translation faces a fundamental trilemma: these large, negatively charged molecules must overcome * enzymatic degradation in circulation, bypass complex cellular barriers for intracellular delivery, and avoid triggering unwanted immunogenic responses*—challenges that constitute the central delivery problem in nucleic acid therapeutics [2] [12]. The resolution of this trilemma hinges on the development of sophisticated delivery systems that can navigate these interconnected obstacles while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

The evolution of delivery platforms has progressed from viral vectors to non-viral systems, with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) emerging as clinically validated carriers through their success in siRNA therapeutics and mRNA vaccines [13] [14]. These systems represent two philosophical approaches: targeted delivery systems designed for precise cellular recognition through surface ligands, and non-targeted systems that rely on passive accumulation and intrinsic cellular uptake mechanisms. This review systematically compares these approaches through the lens of overcoming the three central delivery challenges, providing researchers with experimental data and methodological frameworks for evaluating next-generation delivery platforms.

Quantitative Analysis of Delivery Barriers

Enzymatic Degradation Susceptibility

Nucleic acid therapeutics face immediate vulnerability to nucleases upon administration, necessitating protective formulations. The comparative stability data reveals significant differences between naked nucleic acids and those complexed within delivery systems.

Table 1: Comparative Stability of Nucleic Acid Formulations

| Formulation Type | Half-Life in Serum | Protection Mechanism | Key Stabilizing Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naked siRNA | <5 minutes [12] | None | Unmodified phosphodiester backbone |

| Naked mRNA | ~Minutes [14] | None | Susceptible to ribonucleases |

| Chitosan Polyplexes | Hours [12] | Polyelectrolyte complexation | Cationic amine groups form stable complexes |

| Standard LNPs | >24 hours [14] | Encapsulation in lipid bilayer | Ionizable lipid encapsulation protects payload |

| GalNAc-siRNA Conjugates | Enhanced stability [13] | Chemical modification + ligand targeting | Sugar moiety shields from nucleases |

Chemical modifications represent the first line of defense against enzymatic degradation. Early NADs like fomivirsen incorporated phosphorothioate backbones that resist nuclease cleavage, establishing a foundation for later innovations [13]. Contemporary approaches combine structural modifications with encapsulation strategies. In LNP systems, ionizable lipids with pKa values optimized for endosomal escape (typically pH 6.0-6.5) also provide a protective hydrophobic environment that shields nucleic acids from serum nucleases during circulation [15] [14]. Chitosan polyplexes leverage dense cationic charge to form stable complexes that physically block enzyme access through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding [12].

Cellular Uptake Efficiency and Intracellular Trafficking

Cellular internalization represents a critical bottleneck, with significant differences observed between targeted and non-targeted systems. Quantitative microscopy studies reveal that only a fraction of internalized nanoparticles successfully mediate cytosolic delivery.

Table 2: Cellular Uptake and Endosomal Escape Efficiency

| Delivery System | Cellular Uptake Efficiency | Endosomal Escape Rate | Key Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-targeted LNPs | High in hepatocytes (ApoE-mediated) [14] | ~1-4% of internalized RNA [15] | Galectin-9 recruitment assays [15] |

| Ligand-targeted LNPs | Enhanced in specific cell types [16] | Varies with targeting moiety | Fluorescence co-localization microscopy |

| GalNAc-siRNA Conjugates | >60% in hepatocytes [13] | ASGPR-mediated efficient release | Receptor binding/internalization assays |

| Chitosan Polyplexes | Moderate (charge-dependent) [12] | pH-dependent (varies with chitosan DDA%) | Endosomal dye release assays |

Super-resolution microscopy of LNP trafficking has identified multiple distinct inefficiencies in the cytosolic delivery pathway [15]. Live-cell imaging demonstrates that both siRNA and mRNA LNPs trigger galectin-9 recruitment to damaged endosomes, with only 67-74% of damaged vesicles containing detectable siRNA cargo and approximately 20% containing mRNA cargo [15]. This suggests significant payload segregation during endosomal sorting. Furthermore, only a small fraction of the nucleic acid cargo contained within damaged endosomes is actually released to the cytosol, creating a compound inefficiency where only a minority of internalized LNPs both damage endosomes and release their payload [15] [17].

Targeted systems like GalNAc-siRNA conjugates bypass these inefficiencies through receptor-mediated uptake, achieving significantly higher functional delivery rates to hepatocytes by leveraging the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) [13]. Similarly, ligand-conjugated chitosan polyplexes functionalized with folate, transferrin, or RGD peptides demonstrate enhanced cellular uptake through specific receptor interactions compared to their non-targeted counterparts [12].

Immunogenicity Profiles

The immunostimulatory potential of NADs varies significantly by formulation, with recognition by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) triggering potentially therapeutic or adverse immune activation.

Table 3: Immunogenicity Profile Comparison

| Delivery System | Immune Activation Pathway | Strategies for Mitigation | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified mRNA | TLR7/8, RIG-I, PKR recognition [2] | Nucleoside modifications (pseudouridine) [2] | Enhanced vaccine responses, undesirable for protein replacement |

| LNP-mRNA | Minor innate immune activation [14] | Purification to remove dsRNA contaminants | Generally favorable safety profile in vaccines |

| Chitosan Polyplexes | Varies with degree of deacetylation [12] | Chemical modification to reduce cationic charge density | Can be tuned for adjuvant or stealth properties |

| GalNAc-siRNA | Minimal immune activation [13] | Extensive chemical modification of siRNA backbone | Suitable for chronic administration |

The immunogenicity landscape reveals a delicate balance—while excessive immune activation can cause adverse effects and reduce therapeutic efficacy, controlled immune stimulation may be desirable for vaccine applications. The success of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 demonstrated how nucleoside modifications (pseudouridine) combined with LNP delivery could achieve the optimal balance: sufficient innate immune sensing to generate robust adaptive immunity without excessive reactogenicity [2]. For non-vaccine applications, advanced LNP systems incorporate PEGylated lipids and optimized ionizable lipids that minimize immune recognition, while chitosan formulations can be chemically modified to reduce their inherent immunostimulatory properties [12] [14].

Experimental Approaches for Barrier Analysis

Methodologies for Assessing Enzymatic Stability

Protocol 1: Serum Stability Assay

- Preparation: Formulate nucleic acids with candidate delivery systems (LNPs, polyplexes) and label with appropriate fluorophores (e.g., Cy5, AF647).

- Incubation: Expose formulations to 50-90% human or fetal bovine serum at 37°C.

- Sampling: Remove aliquots at predetermined time points (0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480 minutes).

- Analysis: Separate intact nucleic acids using gel electrophoresis or quantify using fluorescence-based techniques after degradation.

- Quantification: Calculate half-life by plotting percentage of intact nucleic acid versus time [12] [14].

This fundamental protocol enables direct comparison of protective capabilities across delivery platforms. For targeted systems, stability should be assessed both with and without targeting ligands to determine their potential impact on nuclease resistance.

Methodologies for Evaluating Intracellular Fate

Protocol 2: Live-Cell Imaging of Endosomal Escape

- Cell Preparation: Seed appropriate cell lines in glass-bottom dishes and culture to 60-80% confluence.

- Transfection: Add fluorescently labeled nucleic acid formulations (50-100 nM final concentration).

- Staining: Co-transfect with galectin-9-GFP or other membrane damage markers [15].

- Imaging: Conduct time-lapse microscopy using confocal or super-resolution systems at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Analysis: Quantify co-localization of nucleic acid signal with damage markers and track individual endosomes over time [15] [17].

This approach directly visualizes the critical endosomal escape step, identifying formulations that efficiently mediate cytosolic release versus those trapped in endolysosomal pathways. For targeted systems, receptor dependence can be validated through competitive inhibition with free ligands.

Visualization 1: The intracellular trafficking pathway of lipid nanoparticles, highlighting key decision points between functional cytosolic release and non-productive degradation pathways, with quantitative estimates based on live-cell imaging data [15] [17].

Methodologies for Immunogenicity Assessment

Protocol 3: Innate Immune Response Profiling

- Cell Models: Use primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or specialized reporter cell lines (HEK-Blue hTLR).

- Stimulation: Treat cells with nucleic acid formulations across a concentration range (0.1-10 μg/mL).

- Cytokine Measurement: Quantify IFN-α, TNF-α, IL-6, and IP-10 production via ELISA at 6-24 hours post-treatment.

- Pathway Analysis: Assess specific PRR activation (TLR3/7/8, RIG-I, MDA5) using knockout cells or inhibitory oligonucleotides.

- Flow Cytometry: Evaluate dendritic cell maturation markers (CD80, CD86, CD83) [2] [14].

This comprehensive profiling enables researchers to identify the specific immune pathways activated by delivery systems and optimize formulations for either stealth delivery (protein replacement) or controlled immunostimulation (vaccine applications).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Nucleic Acid Delivery Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Damage Sensors | Galectin-9-GFP, Galectin-3-mCherry [15] | Visualizing endosomal escape | Galectin-9 most sensitive for LNP-induced damage |

| Endosomal Markers | Rab5-GFP (early), Rab7-mCherry (late), LAMP1-RFP (lysosomal) [15] | Tracking intracellular trafficking | Multiple markers needed for complete pathway mapping |

| Ionizable Lipids | DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315 [14] | LNP formulation | pKa optimization critical for endosomal escape |

| Targeting Ligands | GalNAc, Folate, Transferrin, RGD peptides [13] [12] | Cell-specific targeting | Receptor density and internalization capacity vary |

| Cationic Polymers | Chitosan (varied DDA%), PEI, PAMAM dendrimers [12] | Polyplex formation | Charge density and molecular weight determine efficacy |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Cy5-labeled siRNA, AF647-mRNA [15] | Particle tracking and quantification | Consider fluorophore quenching in intact nanoparticles |

Integrated Analysis: Targeted Versus Non-Targeted Systems

The comparative analysis reveals a nuanced landscape where targeted and non-targeted systems each occupy distinct therapeutic niches. Non-targeted LNP systems excel in applications where hepatic delivery is desirable, leveraging endogenous ApoE-mediated targeting to hepatocytes with established safety profiles [14]. Their formulation simplicity and scalability make them ideal for rapid vaccine deployment and liver-directed therapies like patisiran [13].

Receptor-targeted systems like GalNAc-siRNA conjugates demonstrate superior efficiency for specific cell types, achieving robust gene silencing at significantly lower doses through enhanced cellular uptake and reduced non-specific distribution [13]. Similarly, antibody-conjugated or ligand-functionalized nanoparticles show promise for extrahepatic targeting, though their clinical translation has been hampered by complex manufacturing and potential immunogenicity [16].

Visualization 2: Comparative mechanisms of non-targeted (ApoE/LDLR-mediated) versus targeted (ligand-receptor-mediated) delivery systems, highlighting their distinct cellular uptake pathways and tissue tropism [13] [14].

Emerging hierarchical targeting approaches represent the next frontier, combining multiple targeting modalities within a single system. These platforms may incorporate initial tissue-level targeting through size optimization, followed by cell-specific targeting through surface ligands, and finally subcellular localization through organelle-targeting peptides [16]. The development of stimuli-responsive systems that transform their properties at different biological milestones offers particular promise for addressing the paradoxical requirements of circulation, penetration, and internalization that have limited previous generations of delivery systems [16].

The resolution of the central delivery challenge requires continued innovation across multiple fronts. While significant progress has been made in understanding and overcoming enzymatic degradation and immunogenicity, intracellular delivery barriers remain the most significant bottleneck, with even advanced LNP systems achieving only modest endosomal escape efficiency [15] [17]. Future research directions should prioritize the development of more sophisticated delivery systems that dynamically adapt to their environment, the discovery of novel endosomolytic agents that enhance cytosolic release without excessive toxicity, and the creation of standardized assessment protocols that enable direct comparison across platforms.

The convergence of nucleic acid therapeutics with advances in bionanomaterials science, microfluidic production technologies like the NANOSPRESSO concept for point-of-care manufacturing, and artificial intelligence-driven formulation optimization promises to accelerate this progress [11] [18]. As these fields mature, the distinction between targeted and non-targeted systems may blur, giving rise to adaptive delivery platforms capable of navigating the entire delivery cascade—from administration to subcellular site of action—with unprecedented precision. Through continued systematic evaluation of how emerging platforms address the fundamental challenges of enzymatic degradation, cellular barriers, and immunogenicity, researchers can unlock the full therapeutic potential of nucleic acid medicines across an expanding range of clinical applications.

The therapeutic application of nucleic acids—including DNA, mRNA, and siRNA—represents a revolutionary advance in treating genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases. However, the clinical success of these therapies is fundamentally constrained by the challenge of delivering these fragile macromolecules to their intended cellular targets [19] [20]. Nucleic acids exhibit poor inherent stability, rapid clearance from circulation, and limited cellular uptake due to their size and negative charge [20]. To overcome these biological barriers, scientists have developed sophisticated delivery systems that can be broadly categorized into non-targeted and targeted approaches.

Non-targeted delivery, primarily relying on passive accumulation mechanisms, formed the foundation of nanocarrier-based therapies. In contrast, targeted delivery employs active homing mechanisms to improve precision and therapeutic outcomes [21] [22]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these core strategies, focusing on their operational principles, experimental evidence, and practical implementation for research and therapeutic development.

Fundamental Mechanisms: Passive vs. Active Targeting

Non-Targeted (Passive) Delivery

Non-targeted delivery systems operate primarily through the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, a physiological phenomenon unique to solid tumors and inflamed tissues [21] [22]. Tumor vasculature is characterized by irregular architecture with gaps between endothelial cells (ranging from 100 to 1000 nanometers), combined with impaired lymphatic drainage. This combination allows nanocarriers (typically <150 nm) to extravasate from the bloodstream into tumor tissue and accumulate there over time [21].

The efficiency of passive targeting is governed by the nanocarrier's physicochemical properties:

- Size: Optimal particle sizes are approximately 100 nm for prolonged circulation and effective tumor accumulation [21].

- Surface Characteristics: Modification with hydrophilic polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) creates a "stealth" effect, reducing opsonization and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), thereby extending circulation half-life [21] [22].

- Shape and Elasticity: These properties influence margination (movement toward vessel walls), extravasation potential, and cellular uptake profiles [22].

Despite its conceptual elegance, the EPR effect demonstrates significant heterogeneity across tumor types and individual patients, which limits the consistent clinical application of purely passive targeting strategies [22].

Targeted (Active) Delivery

Active targeting enhances delivery precision by decorating nanocarriers with targeting ligands that recognize and bind to specific receptors overexpressed on target cells [21] [22] [23]. This approach builds upon the passive accumulation foundation but adds a specific recognition layer.

Common targeting moieties include:

- Antibodies and Antibody Fragments: Provide high specificity and affinity for cell-surface antigens [23].

- Peptides: Often derived from natural ligands or discovered through phage display screens.

- Aptamers: Short, structured oligonucleotides with selective binding capabilities.

- Small Molecules: Such as folate for targeting folate receptor-overexpressing cancers.

The binding process, mediated by these ligands, can trigger receptor-mediated endocytosis, enhancing cellular internalization and potentially influencing intracellular trafficking [21]. A prominent example is the development of Antibody-Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles (Ab-LNPs), where antibodies conjugated to the LNP surface redirect particles from the liver to specific cells, such as T cells (via CD4) or lung endothelium (via PECAM-1) [23].

The diagram below illustrates the core mechanistic differences between these two fundamental strategies.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The selection between targeted and non-targeted strategies involves trade-offs across multiple performance parameters. The following table synthesizes quantitative and qualitative data from preclinical and clinical studies to illustrate these key differences.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Delivery Systems

| Performance Parameter | Non-Targeted Systems | Targeted Systems | Experimental Evidence & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Accumulation Efficiency | Typically <1% of injected dose [22] | Can reach ~10% in optimized systems; AI-optimized LNPs showed up to 89% in preclinical models [24] | High variability observed; depends on tumor model and EPR heterogeneity [22] |

| Cellular Uptake Mechanism | Non-specific fluid-phase pinocytosis [21] | Receptor-mediated endocytosis [21] [23] | Active targeting enhances uptake by 30-fold in specific cells (e.g., CD4+ T cells) [23] |

| Liver Accumulation | High (35-40% hepatic sequestration) [24] | Significantly reduced with proper targeting | Anti-PECAM-1 Ab-LNPs inhibited hepatic uptake, redirecting to lungs [23] |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Moderate; improves pharmacokinetics [22] | Enhanced due to higher target site concentration | CPX-351 (passive) showed survival benefit in AML; Ab-LNPs enable in vivo CAR-T generation [22] [23] |

| Specificity & Off-Target Effects | Limited; relies on EPR effect only [22] | High for target cells; reduces systemic toxicity | Targeted LNPs reduce risks of acute liver toxicity and systemic side effects [23] |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Relatively simple [22] | Complex due to conjugation chemistry and characterization [22] | Scale-up challenges for actively targeted nanocarriers present translational hurdles [22] |

| Clinical Translation Status | Multiple FDA-approved products (e.g., Doxil, Onpattro) [22] [20] | Early clinical trials (e.g., Capstan's CPTX2309) [23] | No actively targeted NCs approved yet as of 2018; clinical progress emerging [22] [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluation

Protocol: Evaluating Passive Targeting via the EPR Effect

Objective: Quantify the tumor accumulation and biodistribution of non-targeted nanocarriers in a murine model.

Materials:

- Nanocarrier: PEGylated liposomes (~100 nm) loaded with a near-infrared fluorophore (e.g., DiR) [21].

- Animal Model: Mice bearing subcutaneous xenograft tumors.

- Imaging System: In vivo fluorescence imaging system (e.g., IVIS).

- Analytical Tools: HPLC or gamma counter if using radiolabeled carriers.

Methodology:

- Formulation & Characterization: Prepare and characterize liposomes for size (100 nm optimal), PDI, zeta potential, and dye encapsulation efficiency [21].

- Administration: Inject DiR-liposomes intravenously via the tail vein.

- Longitudinal Imaging: Anesthetize mice and image at predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 4, 24, 48 hours) to track biodistribution and tumor accumulation.

- Ex Vivo Analysis: At endpoint (e.g., 48 hours), euthanize animals, collect tumors and major organs, and image ex vivo to quantify fluorescence intensity per gram of tissue.

- Data Analysis: Calculate tumor-to-background ratios and % injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) [22].

Key Measurements:

- Blood Circulation Half-life: Determined by serial blood collection.

- Tumor Accumulation: Peak accumulation typically occurs between 24-48 hours [22].

- EPR Heterogeneity: Compare accumulation between different tumor models.

Protocol: Evaluating Active Targeting Efficiency

Objective: Compare the targeting efficiency and cellular uptake of ligand-functionalized vs. non-functionalized nanocarriers in vitro and in vivo.

Materials:

- Nanocarriers: Ligand-decorated LNPs (e.g., anti-CD4 Ab-LNPs) and non-targeted control LNPs [23].

- Cell Model: CD4+ T cells for in vitro studies.

- Animal Model: Appropriate disease model.

- Flow Cytometer: For quantifying cellular uptake.

Methodology:

- In Vitro Binding and Uptake:

- Incubate targeted and non-targeted LNPs (loaded with a fluorescent reporter) with CD4+ T cells.

- Use flow cytometry to quantify mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) per cell after incubation.

- Perform competitive inhibition by pre-blocking receptors with free antibodies [23].

- In Vivo Targeting:

- Systemically administer both LNP formulations to animal models.

- After 24 hours, harvest target tissues/organs and process into single-cell suspensions.

- Use flow cytometry or confocal microscopy to quantify particle delivery to specific cell populations.

- Functional Assessment:

- Load LNPs with therapeutic mRNA (e.g., Cre recombinase).

- Measure functional output (e.g., gene recombination efficiency) versus non-targeted controls [23].

Key Measurements:

- Fold-Enhancement in Delivery: Targeted vs. non-targeted MFI.

- Specificity Index: Uptake in target cells vs. non-target cells.

- Functional Payload Delivery: Efficacy of delivered nucleic acids.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of delivery strategies requires specific reagents and materials. The following table catalogues key components for formulating and evaluating targeted and non-targeted systems.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Nucleic Acid Delivery Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Core component of LNPs; enables nucleic acid encapsulation and endosomal escape [24] | SM-102, DLin-MC3-DMA; pKa optimization critical for performance |

| PEGylated Lipids | Confers "stealth" properties, reduces MPS clearance, modulates particle size [21] [24] | DMG-PEG, DSPE-PEG; concentration and PEG chain length affect circulation time |

| Targeting Ligands | Confers specificity for active targeting strategies [21] [23] | Monoclonal antibodies (e.g., anti-PECAM-1, anti-CD4), peptides, aptamers |

| Fluorescent Probes | Tracking and quantifying biodistribution and cellular uptake [22] | Near-infrared dyes (DiR, Cy5.5); compatible with in vivo imaging |

| Characterization Instrumentation | Measuring critical quality attributes of nanocarriers [21] | Dynamic Light Scattering (size, PDI), Zetasizer (zeta potential), NMR/TLC (lipid quantification) |

| Specialized Lipids for Conjugation | Provides chemical handle for ligand attachment [23] | DSPE-PEG-Maleimide; reacts with thiol groups on antibodies or peptides |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of nucleic acid delivery is rapidly evolving, with several emerging technologies poised to address current limitations.

Artificial Intelligence in Formulation Design: Machine learning models, including graph neural networks (GNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs), are accelerating LNP optimization by virtually screening millions of lipid structures. These AI-driven approaches can predict structure-property relationships with R² > 0.85, significantly reducing development timelines [24]. For instance, GAN-generated lipids have demonstrated structural novelty while maintaining higher encapsulation efficiency compared to traditionally developed lipids.

Advanced Targeting Modalities: Bispecific antibodies and peptide conjugates are expanding the repertoire of targeting options. Furthermore, researchers are exploring "dual targeting" approaches that combine two different siRNA payloads or targeting ligands to achieve synergistic effects and address tumor heterogeneity [10] [23].

Novel Delivery Platforms: Beyond conventional LNPs, platforms such as extracellular vesicles, polymeric nanoparticles, and hybrid systems offer complementary advantages for specific applications. The integration of stimuli-responsive elements (e.g., pH-sensitive linkers) enables triggered payload release in the tumor microenvironment [22].

The convergence of these advanced technologies with a deeper understanding of biological barriers will continue to push the boundaries of what is achievable with nucleic acid therapeutics, potentially enabling effective treatment for a broader range of diseases.

The field of RNA therapeutics represents one of the most transformative advancements in modern medicine, fundamentally changing our approach to treating genetic disorders, infectious diseases, and cancer. This journey from conceptual foundations to clinical reality has been marked by key scientific breakthroughs that progressively addressed fundamental challenges of RNA instability, immunogenicity, and delivery. The evolution from first-generation antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to the sophisticated RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutics and mRNA vaccines of today illustrates a remarkable scientific trajectory spanning nearly five decades [25]. This progression has occurred within the broader context of evaluating targeted versus non-targeted nucleic acid drug delivery systems, a critical determinant of therapeutic efficacy and safety. The development of these modalities underscores a continuous refinement in our ability to precisely modulate gene expression for therapeutic benefit, moving from simple hybridization-based strategies to complex cellular machinery hijacking and genetic reprogramming [2]. As the field matures, understanding these historical milestones provides invaluable insights for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to advance the next generation of nucleic acid therapeutics.

Major Historical Breakthroughs in RNA Therapeutics

The development of RNA therapeutics has followed a defined pathway of discovery and innovation, with each milestone building upon previous insights to overcome specific biological challenges. The table below chronicles the pivotal moments that have shaped the current landscape.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in RNA Therapeutics Development

| Year | Breakthrough Discovery/Event | Key Researchers/Entities | Significance and Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | First ASO Concept | Zamecnik and Stephenson [25] | Pioneered use of synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide to inhibit Rous sarcoma virus replication; established antisense principle |

| 1998 | RNA Interference (RNAi) Discovery | Fire and Mello [2] | Discovered potent gene silencing by double-stranded RNA in C. elegans; unveiled new regulatory pathway |

| 2001 | siRNA in Mammalian Cells | Elbashir et al. [25] | Demonstrated siRNA could silence genes in mammalian cell lines; enabled therapeutic application |

| 2003 | First In Vivo siRNA Proof | — | Showed intravenous Fas siRNA protected mice from fulminant hepatitis [2] |

| 2005 | mRNA Nucleoside Modification | Karikó and Weissman [2] | Pseudouridine modification reduced mRNA immunogenicity; crucial for therapeutic application |

| 2006 | Nobel Prize for RNAi | Fire and Mello [1] | Recognized foundational importance of RNA interference discovery |

| 2016 | First SMA ASO Drug (Nusinersen) | Biogen/Ionis [25] | FDA approved splice-switching ASO for spinal muscular atrophy; validated steric-blocking mechanism |

| 2018 | First siRNA Drug (Patisiran) | Alnylam [25] | FDA approved LNP-formulated siRNA for hATTR amyloidosis; validated RNAi clinical application |

| 2020 | mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines | Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna [25] | Global validation of mRNA platform; demonstrated rapid vaccine development and scalability |

| 2023 | First CRISPR/Cas9 Therapy (Exa-cel) | Vertex/CRISPR Tx [25] | FDA approved for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia; inaugurated therapeutic gene editing |

| 2024+ | Emerging Modalities (saRNA, circRNA) | Multiple entities [25] | Investigation of self-amplifying and circular RNAs for enhanced stability and durability |

The initial concept of antisense therapeutics emerged from the straightforward principle of Watson-Crick base pairing, with synthetic oligonucleotides designed to bind complementary RNA sequences and physically block translation or induce degradation [2]. The discovery of RNA interference revealed a natural, potent cellular pathway for gene silencing that could be harnessed therapeutically with synthetic small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), offering greater potency and specificity than early ASOs [1]. Parallel work on mRNA therapeutics focused on overcoming inherent instability and immunogenicity through nucleoside modifications and delivery system optimization, culminating in the dramatic success of COVID-19 vaccines [26]. Most recently, CRISPR-based technologies have expanded the toolbox to include precise gene editing, while novel RNA structures like circular RNAs and self-amplifying RNAs promise further enhancements in stability and therapeutic duration [25].

Comparative Analysis of Approved RNA Therapeutics

The clinical translation of RNA therapeutics has yielded numerous approved drugs across different modalities, each with distinct mechanisms, chemical modifications, and delivery strategies. The following table provides a comprehensive comparison of selected approved RNA therapeutics, highlighting the evolution from early to modern approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Approved RNA Therapeutics Across Modalities

| Therapeutic (Brand Name) | RNA Modality | Target/Indication | Key Modifications | Delivery System | Year Approved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nusinersen (Spinraza) | ASO (splice-switching) | SMN2 gene / Spinal Muscular Atrophy [25] | 2'-MOE phosphorothioate [1] | Intrathecal injection (no carrier) [1] | 2016 |

| Patisiran (Onpattro) | siRNA | Transthyretin (hATTR amyloidosis) [25] | 2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro [1] | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) [25] | 2018 |

| Givosiran (Givlaari) | siRNA | ALAS1 / Acute Hepatic Porphyria [27] | Extensive chemical stabilization [1] | GalNAc conjugate (liver-targeted) [25] | 2019 |

| Inclisiran (Leqvio) | siRNA | PCSK9 / Hypercholesterolemia [25] | Stabilizing modifications | GalNAc conjugate (liver-targeted) [28] | 2021 |

| mRNA-1273 (Moderna) | mRNA vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein [25] | N1-methylpseudouridine [26] | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) [25] | 2020 (EUA) 2022 (full) |

| COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) | mRNA vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein [25] | N1-methylpseudouridine [26] | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) [25] | 2020 (EUA) 2022 (full) |

The comparison reveals a clear evolutionary trajectory in delivery strategies. Early approved ASOs like Nusinersen utilized local administration (intrathecal) without complex delivery systems, bypassing distribution challenges [1]. The first siRNA drug, Patisiran, required sophisticated lipid nanoparticles for systemic administration and tissue penetration [25]. Subsequent siRNA therapeutics (Givosiran, Inclisiran) adopted more precise GalNAc conjugation for efficient liver targeting without the complexity of nanoparticles, reflecting a trend toward targeted delivery approaches [25] [28]. Meanwhile, mRNA vaccines necessitated comprehensive LNP formulations to protect the large, fragile mRNA molecules and facilitate cellular uptake and endosomal escape [6]. The chemical modification strategies have also evolved, with early ASOs relying predominantly on phosphorothioate backbones and 2'-sugar modifications, while siRNAs and mRNA incorporate more diverse modifications including 2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro, and pseudouridine derivatives to enhance stability, reduce immunogenicity, and improve translational efficiency [26].

Delivery Systems: Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Approaches

The efficacy of RNA therapeutics is inextricably linked to delivery strategies, which have evolved from simple local administration to sophisticated targeted systems. The primary challenge remains overcoming multiple biological barriers: protection from nucleases, clearance by renal filtration and mononuclear phagocyte system, cellular uptake, endosomal escape, and intracellular trafficking to the correct subcellular compartment [6]. Different RNA modalities have distinct subcellular destinations—siRNA and mRNA function in the cytoplasm, while ASOs targeting nuclear pre-mRNA and CRISPR systems require nuclear access [6].

Non-Targeted Delivery Systems often rely on physical or chemical methods to enhance cellular uptake. Cationic lipids and polymers form nanoparticles through electrostatic interactions with negatively charged nucleic acids, protecting them and promoting cellular entry via endocytosis [6]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), used in Patisiran and mRNA vaccines, represent the most clinically advanced non-targeted approach, offering robust encapsulation and endosomal escape capabilities but predominantly accumulating in the liver and spleen after systemic administration [25]. While effective for hepatocyte targets and intramuscular vaccines, this limited tropism restricts applications for extrahepatic diseases.

Targeted Delivery Systems employ specific ligands to direct therapeutics to particular cell types or tissues. The most successful example is GalNAc conjugation, which leverages high-affinity binding to the asialoglycoprotein receptor abundantly expressed on hepatocytes [29]. This approach has revolutionized siRNA therapeutics for liver diseases, enabling subcutaneous administration with efficient, specific uptake at lower doses and reduced off-target effects [28]. Emerging targeting strategies include cell-penetrating peptides, antibody conjugates, and ligand-modified LNPs directed to extrahepatic tissues like muscle, CNS, and tumors [29]. For instance, ASOs conjugated to muscle-targeting ligands have shown improved delivery in preclinical models of myotonic dystrophy [29].

The choice between targeted and non-targeted approaches involves trade-offs between specificity, complexity, manufacturing, and therapeutic application. Targeted systems generally offer superior pharmacokinetics and reduced side effects but require identification of appropriate receptors and ligand conjugation. Non-targeted systems provide broader applicability and easier formulation but may necessitate local administration or tolerate wider tissue distribution.

Figure 1: Pharmacological Barriers and Delivery Strategies for RNA Therapeutics. The diagram illustrates the sequential biological barriers that RNA therapeutics encounter and how targeted and non-targeted delivery systems employ different mechanisms to overcome them, resulting in distinct distribution outcomes [6].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Delivery Systems

Robust experimental methodologies are essential for evaluating the efficacy of nucleic acid delivery systems. The following protocols represent standard approaches used in the field to assess key parameters from in vitro characterization to in vivo performance.

Polyplex Formation and Stability Analysis

This protocol evaluates the formation and stability of nucleic acid-carrier complexes ("polyplexes"), a critical determinant of delivery efficiency [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Nucleic Acid Cargo: siRNA, ASO, or mRNA diluted in nuclease-free buffer

- Delivery Carrier: Cationic polymer (e.g., PEI), lipid nanoparticle formulation, or GalNAc-conjugate

- Gel Electrophoresis System: Agarose, loading dye, ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe stain

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument: For particle size and zeta potential measurement

- Heparin Sulfate Solution: For polyplex stability challenge

Procedure:

- Polyplex Formation: Prepare polyplexes at various carrier:nucleic acid weight or charge (N:P) ratios by adding the carrier solution to nucleic acid with gentle vortexing. Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Gel Retardation Assay: Load polyplexes onto 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Run gel at 100V for 45 minutes. Visualize under UV light—complete nucleic acid retention in wells indicates efficient complexation.

- Particle Characterization: Dilute polyplexes in distilled water or specific buffer. Measure hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) by DLS. Determine zeta potential using laser Doppler anemometry.

- Heparin Competition Assay: Incubate pre-formed polyplexes with increasing concentrations of heparin sulfate (a polyanion) for 30 minutes. Run on agarose gel to determine the minimum heparin concentration that dissociates polyplexes, indicating complex stability.

In Vitro Transfection Efficiency and Gene Silencing

This protocol assesses the functional delivery of RNA therapeutics in cell culture models, quantifying target gene modulation [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: Relevant to disease model (e.g., hepatocytes for liver-targeted therapeutics)

- Transfection Medium: Serum-free or reduced-serum medium appropriate for cell type

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR) System: Primers for target mRNA, reverse transcription kit, SYBR Green master mix

- Western Blot System: Antibodies against target protein and loading control

- Cell Viability Assay: MTT, MTS, or CellTiter-Glo reagents

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells in 24- or 96-well plates at appropriate density to reach 60-80% confluency at time of transfection.

- Treatment Application: Dilute nucleic acid polyplexes in serum-free medium. Replace cell culture medium with polyplex-containing medium. For GalNAc-conjugates, add directly to culture medium containing serum.

- Incubation and Harvest: Incubate cells for 24-72 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Harvest cells for RNA extraction (qPCR) or protein extraction (Western blot) at appropriate timepoints.

- Gene Expression Analysis:

- Extract total RNA and synthesize cDNA.

- Perform qPCR with target-specific primers and normalize to housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin).

- Calculate percentage gene silencing relative to untreated controls.

- Protein Expression Analysis:

- Perform Western blotting with target-specific antibodies.

- Quantify band intensity normalized to loading control.

- Viability Assessment: Treat parallel wells with identical formulations. After 24-48 hours, add MTT reagent and measure absorbance according to manufacturer's protocol. Express viability as percentage of untreated controls.

In Vivo Biodistribution and Efficacy

This protocol evaluates the tissue distribution and pharmacological activity of RNA therapeutics in animal models, providing critical preclinical data [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Animal Model: Appropriate disease model (e.g., transgenic mice for human target)

- Formulation: RNA therapeutic in final delivery system (LNP, conjugate) in appropriate buffer for injection

- IVIS Imaging System (if using labeled formulations) or qPCR equipment for biodistribution

- Sample Collection: Tubes for tissue and blood collection, RNA stabilization reagents

- Clinical Chemistry Analyzer: For relevant disease biomarkers (e.g., serum TTR for amyloidosis models)

Procedure:

- Dosing Groups: Randomize animals into groups (n=5-8): untreated control, vehicle control, and treated groups with various doses/formulations.

- Administration: Administer formulation via relevant route (intravenous, subcutaneous, intrathecal). For biodistribution studies, use fluorescently labeled RNA (e.g., Cy5) or carrier.

- Biodistribution Analysis:

- At predetermined timepoints (e.g., 1, 4, 24 hours), euthanize animals and collect tissues (liver, spleen, kidney, lung, target tissue).

- For fluorescent imaging, image intact organs using IVIS system and quantify fluorescence intensity.

- For qPCR-based biodistribution, extract tissue RNA and quantify therapeutic RNA levels using specific probes.

- Pharmacodynamic Assessment:

- At therapeutic timepoints (days to weeks post-dose), collect tissue and blood samples.

- Isolate target tissue RNA and measure target mRNA reduction by qPCR.

- Measure relevant protein biomarkers in serum or tissue by ELISA or Western blot.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare results using appropriate tests (t-test, ANOVA) with significance at p<0.05.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research in RNA therapeutics relies on specialized reagents and materials that enable the design, production, and evaluation of novel therapeutic candidates. The following table catalogizes key solutions essential for working in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RNA Therapeutics Development

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Primary Function and Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Nucleotides | TriLink BioTechnologies, Thermo Fisher | N1-methylpseudouridine, 2'-fluoro, 2'-O-methyl ribose substitutions; reduce immunogenicity, enhance stability [26] |

| Cationic Lipids/Polymers | Avanti Polar Lipids, Sigma-Aldrich | DOTAP, MC3, PEI; form nanostructured complexes with nucleic acids for cellular delivery [6] |

| GalNAc Conjugation Reagents | BroadPharm, Sigma-Aldrich | N-Acetylgalactosamine derivatives with activated esters; create liver-targeted oligonucleotide conjugates [29] |

| In Vitro Transcription Kits | New England Biolabs, Thermo Fisher | T7 polymerase, capping enzymes, nucleotide mixes; produce research-grade mRNA [2] |

| Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation Systems | Precision NanoSystems | Microfluidic chips and instruments; manufacture reproducible, size-controlled LNPs [25] |

| RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC) Loading Assays | Reaction Biology, Eurofins | Components to monitor siRNA strand loading into RISC; assess functional potential [1] |

| Endosomal Escape Reporters | Thermo Fisher, ATCC | Galectin-8-GFP, fluorescent dyes with pH-sensitive properties; quantify endosomal release efficiency [6] |

These specialized research tools address the unique challenges of RNA therapeutic development. Modified nucleotides are fundamental for overcoming the inherent instability and immunogenicity of natural RNA, with specific modifications like N1-methylpseudouridine proven critical for therapeutic mRNA applications [26]. Cationic lipids and polymers serve as building blocks for non-viral delivery systems, enabling researchers to formulate and screen nanocarriers for specific applications [6]. The availability of GalNAc conjugation reagents has democratized the development of targeted siRNA therapeutics, mirroring the approach used in clinically approved products [29]. Sophisticated formulation systems allow laboratories to produce clinical-grade nanoparticles at benchtop scale, while functional assays for RISC loading and endosomal escape provide critical insights into the intracellular trafficking and mechanism of action beyond simple gene expression changes.

Figure 2: RNA Therapeutic Development Workflow. The diagram outlines the key stages in the research and development of RNA therapeutics, from initial design to clinical translation, highlighting essential tools and assays employed at each stage [25] [6] [26].

The journey from first-generation ASOs to modern RNAi therapeutics and mRNA vaccines represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical development, demonstrating the power of leveraging natural biological processes for therapeutic benefit. This evolution has been characterized by successive innovations addressing the fundamental challenges of nucleic acid delivery, with a clear trend toward increasingly sophisticated targeted approaches. The historical progression from simple antisense principles to the complex orchestration of RNA interference and genetic reprogramming underscores the remarkable acceleration of this field [25]. The critical importance of delivery systems is evident throughout this history, with breakthroughs in GalNAc conjugation and lipid nanoparticle formulation enabling the transition from laboratory concepts to clinical medicines [29] [6].

Future developments in RNA therapeutics will likely focus on expanding beyond current limitations, particularly the challenge of extrahepatic delivery [28]. Next-generation delivery technologies targeting the central nervous system, muscle, and other tissues are already in development, promising to broaden the therapeutic landscape [29]. Emerging modalities such as circular RNAs, self-amplifying RNAs, and RNA editing technologies represent the next frontier, offering potential solutions for enhanced durability, reduced dosing, and expanded therapeutic applications [25]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into RNA design and delivery optimization promises to accelerate the development process and enhance the precision of future therapeutics [28]. As the field continues to mature, the historical milestones chronicled in this review serve as both foundation and inspiration for the next generation of innovations that will further expand the boundaries of what is possible with RNA-targeted medicines.

Delivery Platform Architectures: From Passive Carriers to Active Targeting

The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect represents a cornerstone principle in cancer nanomedicine, enabling the passive targeting of therapeutic agents to tumor tissues without requiring specific molecular ligands. This phenomenon leverages the distinctive pathophysiology of solid tumors, which exhibit leaky vasculature with gaps between endothelial cells ranging from 100 nm to 2 μm, and impaired lymphatic drainage that reduces the clearance of accumulated particles [30]. Non-targeted lipid and polymer nanoparticles systematically exploit these anatomical abnormalities to achieve higher drug concentrations at tumor sites while minimizing damage to healthy tissues. For researchers evaluating targeted versus non-targeted delivery systems, understanding the capabilities and limitations of EPR-based strategies provides a crucial baseline for assessing the incremental value of active targeting approaches. While contemporary research increasingly focuses on ligand-functionalized nanoparticles, EPR-mediated delivery continues to offer substantial advantages in simplicity, manufacturability, and regulatory pathway familiarity, with several FDA-approved formulations relying exclusively on this passive targeting mechanism [31].

The clinical relevance of EPR-driven delivery systems continues to evolve, particularly as researchers develop more sophisticated nanoparticle designs that optimize EPR exploitation. Current estimates suggest that nanoparticles leveraging the EPR effect can achieve tumor drug concentrations representing 1–5% of the injected dose per gram of tumor tissue, a significant improvement over the less than 0.1% typically achieved with free-form chemotherapeutic drugs [31]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of lipid and polymer nanoparticle platforms for non-targeted systemic delivery, examining their respective capabilities for harnessing the EPR effect, with specific attention to design parameters that maximize passive accumulation in malignant tissues.

Comparative Analysis of Nanoparticle Platforms for EPR Exploitation

Structural and Functional Characteristics

Different nanoparticle classes exhibit distinct advantages for EPR-mediated delivery based on their structural properties, composition, and drug release kinetics. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major nanoparticle platforms used in non-targeted drug delivery.

Table 1: Comparison of Lipid and Polymer Nanoparticle Platforms for EPR-Based Delivery

| Nanoparticle Type | Optimal Size Range (nm) | Surface Charge Optimization | Drug Loading Capacity | Circulation Half-Life | Key Advantages for EPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | 80-150 | Neutral to slightly negative | High for hydrophilic drugs (aqueous core) and hydrophobic drugs (lipid bilayer) | Moderate to long (PEGylation extends circulation) | Excellent biocompatibility; tunable surface properties; established clinical translation |

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) | 50-150 | Negative | Moderate for lipophilic drugs | Moderate | Enhanced stability over liposomes; controlled release; protection of encapsulated drugs from degradation |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA) | 20-150 | Adjustable (positive for cancer cell targeting) | High for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs | Moderate (depends on polymer biodegradation rate) | Precise controlled release kinetics; mechanical robustness; versatile surface functionalization potential |

| Lipid-Polymer Hybrid NPs (LPHNPs) | 70-130 | Tunable via shell composition | High for diverse drug types | Prolonged (combines advantages of both systems) | Synergistic benefits: stability of polymers + biocompatibility of lipids; core-shell structure for sequential release |

Quantitative Performance Metrics in EPR Exploitation

The effectiveness of nanoparticle systems in leveraging the EPR effect can be quantified through specific performance parameters established in preclinical studies. The following table compares key metrics across different nanoparticle platforms based on experimental data.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Nanoparticle Platforms in Preclinical Models

| Nanoparticle Platform | Tumor Accumulation (% Injected Dose/g) | Peak Accumulation Time Post-Injection | Tumor-to-Normal Tissue Ratio | Key Evidence and Model System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEGylated Liposomes (Doxil) | 3-5% | 24-48 hours | 5-10:1 | FDA-approved; human clinical data; accumulates in various solid tumors via EPR [31] |

| PLGA Nanoparticles | 2-4% | 12-24 hours | 4-8:1 | Demonstrated in lung cancer models; size-dependent accumulation with optimal range of 70-150 nm [30] |

| Lipid-Polymer Hybrid NPs | 3-6% | 24-72 hours | 8-15:1 | Shown in colorectal cancer and melanoma models; enhanced retention due to structural stability [32] [33] |

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles | 1.5-3% | 12-24 hours | 3-6:1 | Documented in breast cancer models; slower release kinetics moderate tumor exposure levels |

Critical Design Parameters for Maximizing EPR Efficacy

Optimizing nanoparticles for EPR-mediated delivery requires careful consideration of several physicochemical parameters that collectively determine in vivo behavior and tumor accumulation:

Size Optimization: Nanoparticles in the 20-150 nm range demonstrate optimal EPR exploitation, as they are small enough to extravasate through leaky tumor vasculature yet large enough to avoid rapid renal clearance. Particles smaller than 5-10 nm are rapidly cleared by renal filtration, while those exceeding 200 nm may be sequestered by the spleen and liver [30]. Liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles can be precisely engineered within this optimal size window through manufacturing control of composition and formulation parameters.

Surface Charge and Functionalization: Cationic nanoparticles typically exhibit higher nonspecific cellular uptake but also increased clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, reducing circulation time and EPR-mediated tumor accumulation. Neutral or slightly negative surfaces (approximately -10 to -15 mV) optimize circulation half-life, while cationic surfaces (positive zeta potential) can enhance cancer cell interaction due to the net negative charge of cancer cell membranes resulting from the Warburg effect [30]. PEGylation creates a steric barrier that reduces opsonization and extends circulation time, enhancing EPR-mediated accumulation.

Drug Release Kinetics: Effective EPR exploitation requires a balance between circulation stability and timely drug release at the tumor site. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPs) exemplify this balance with a core-shell architecture where the polymeric core provides sustained release properties while the lipid shell offers biocompatibility and enhanced stability during circulation [32]. Premature drug release during circulation severely diminishes therapeutic efficacy despite successful tumor accumulation of the carrier itself.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Evaluating EPR

Standardized Protocols for Assessing Nanoparticle Distribution

Establishing robust experimental methodologies is essential for accurately evaluating the EPR effect and comparing nanoparticle performance. The following protocols represent standardized approaches used in preclinical studies:

Protocol 1: Quantitative Biodistribution Analysis Using Radiolabeling

- Nanoparticle Labeling: Incorporate gamma-emitting radioisotopes (e.g., 111In, 99mTc) or fluorescent dyes (e.g., DiR, Cy5.5) into nanoparticle formulations during synthesis. For lipid nanoparticles, incorporate 3H-labeled phospholipids; for polymeric nanoparticles, use 14C-labeled polymers or encapsulate near-infrared fluorophores [31].

- Animal Models: Utilize murine models with subcutaneously implanted xenograft tumors (typically 500-800 mm3 in volume) or genetically engineered spontaneous tumor models. Orthotopic models may provide more realistic vascularization patterns.

- Administration and Tracking: Administer labeled nanoparticles via tail vein injection (dose: 5-20 mg nanoparticles/kg body weight). At predetermined time points (1, 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours), euthanize animals (n=5-8 per time point) and collect tumors and major organs [30].

- Quantification: Measure radioactivity using a gamma counter or fluorescence intensity with an in vivo imaging system. Calculate percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) and tumor-to-normal tissue ratios for comparative analysis.

Protocol 2: Pharmacokinetic and Tumor Accumulation Profiling

- Blood Circulation Kinetics: Collect blood samples (50-100 μL) at serial time points post-injection (5, 15, 30 minutes; 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours). Separate plasma and quantify nanoparticle concentration using appropriate analytical methods (HPLC, fluorescence measurement, or radioactivity counting) [32].

- Data Analysis: Fit plasma concentration-time data to a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model to determine key parameters: elimination half-life (t1/2β), area under the curve (AUC), and clearance (CL). Correlate pharmacokinetic parameters with tumor accumulation metrics.

- Histological Validation: Process tumor tissues for cryosectioning and fluorescence microscopy to visualize nanoparticle distribution within tumor regions. Co-staining with endothelial markers (CD31) assesses perivascular distribution, while staining for hypoxic regions reveals penetration to avascular areas [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for EPR and Nanoparticle Delivery Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315 | Enable efficient nucleic acid encapsulation and endosomal escape | pKa range of 6.2-6.5 optimizes endosomal escape; biodegradable variants reduce accumulation concerns [33] |

| Structural Lipids | DSPC, Cholesterol, DOPE | Form nanoparticle backbone and enhance membrane stability | Cholesterol content (30-50%) modulates membrane rigidity and drug release kinetics [34] |

| PEGylated Lipids | DMG-PEG2000, DSPE-PEG2000 | Provide steric stabilization, reduce protein opsonization, extend circulation | Optimal PEG density (1.5-5 mol%) balances circulation time and cellular uptake; PEG shedding strategies can improve target cell interaction [33] |