Strategies for Improving Oligonucleotide Stability and Binding Affinity: From Chemical Design to Therapeutic Application

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and strategies for enhancing the stability and binding affinity of therapeutic oligonucleotides.

Strategies for Improving Oligonucleotide Stability and Binding Affinity: From Chemical Design to Therapeutic Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and strategies for enhancing the stability and binding affinity of therapeutic oligonucleotides. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of oligonucleotide degradation and molecular recognition. The scope ranges from foundational chemical modifications and backbone engineering to advanced in vitro assessment methodologies, practical troubleshooting for optimization, and comparative validation of different technological approaches. By synthesizing recent research and development trends, this resource aims to support the rational design of more effective and stable oligonucleotide-based therapeutics, particularly for challenging extrahepatic targets.

The Building Blocks: Understanding Oligonucleotide Degradation and Molecular Recognition

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Overcoming Nuclease Degradation

Nuclease degradation rapidly destroys oligonucleotides before they reach their cellular targets. Use this guide to diagnose and solve common issues.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short oligonucleotide half-life in serum/plasma assays | Presence of serum nucleases (e.g., 3'-exonuclease) | Incorporate phosphorothioate (PS) linkages at the 3' and 5' ends [1]. | Run analytical HPLC or capillary gel electrophoresis post-serum exposure to compare full-length oligonucleotide percentage [2]. |

| Multiple truncated sequences in QC analysis | Chemical degradation during synthesis or storage | Optimize synthesis cycle and use scavengers during deprotection. Store oligonucleotides in neutral pH buffers at -20°C [3]. | Use LC-MS to identify and characterize impurity sequences [2]. |

| Loss of activity in in vivo models despite cell culture success | Rapid clearance by nucleases in blood and tissues | Apply comprehensive chemical modification patterns (e.g., 2'-MOE, 2'-F, LNA) throughout the sequence [1]. | Measure bio-distribution and half-life using radiolabeled or fluorescently tagged oligonucleotides [2]. |

| Inconsistent results between batches | Variable nuclease contamination in reagents or buffers | Use nuclease-free reagents and include nuclease inhibitors (e.g., EDTA) in preparation buffers [4]. | Perform gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer run on reagents spiked with intact DNA to test for nuclease activity. |

Guide 2: Solving Poor Cellular Uptake and Endosomal Trapping

Inefficient cellular entry and failure to escape endosomes are major bottlenecks. This guide addresses these delivery barriers.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| High extracellular fluorescence, low intracellular signal (with labeled ON) | Poor internalization across cell membrane | Complex oligonucleotide with a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) like tri-cTatB [5] or use lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [3]. | Analyze cellular uptake via flow cytometry or confocal microscopy. |

| Colocalization of oligonucleotides with endosomal/lysosomal markers | Trapped in endosomes, lack of endosomal escape | Employ endosomolytic agents or strategies like Photochemical Internalization (PCI) [5]. | Measure functional gene knockdown (e.g., qPCR, Western blot) versus a control. Colocalization studies with Lysotracker. |

| Efficient liver uptake but poor delivery to other tissues | Reliance on passive targeting (e.g., GalNAc for hepatocytes) | Explore novel ligand conjugates (e.g., antibodies, peptides) for active targeting of other tissues [1]. | Conduct bio-distribution studies in relevant animal models. |

| Good uptake but low potency (no target engagement) | Inefficient release from delivery vehicle or intracellular sequestration | Optimize the chemical structure of the delivery vehicle (e.g., LNP lipid ratios) or oligonucleotide chemistry to promote release [3]. | Use techniques like FRET to monitor cargo release from the carrier inside the cell. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective chemical modifications to protect oligonucleotides from nuclease degradation without compromising binding affinity?

Combining different modifications is often most effective. Phosphorothioate (PS) linkages in the backbone dramatically increase nuclease resistance and improve pharmacokinetics. For the sugar moiety, 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) and 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) modifications both enhance nuclease stability and increase binding affinity to the target RNA. Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) modifications offer very high binding affinity and stability but require careful design to avoid off-target effects. A common strategy is a "gapmer" design for ASOs, with high-affinity modifications (e.g., 2'-MOE, LNA) on the ends and a central DNA "gap" to support RNase H activity [1].

Q2: Our siRNA shows excellent gene knockdown in vitro but is ineffective in our mouse model. What should we investigate first?

First, check the bio-distribution and delivery system. In vitro delivery often uses transfection reagents that are unsuitable for in vivo use. For in vivo applications, you need a robust delivery vehicle. If targeting the liver, GalNAc conjugation is the gold standard for siRNAs, enabling efficient hepatocyte uptake. For other tissues, investigate lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or other targeting ligands. Second, confirm that the oligonucleotide remains intact in vivo. Extract tissue samples and analyze the oligonucleotide integrity to rule out extensive nuclease degradation [1].

Q3: We observe high cellular uptake with a new CPP, but our oligonucleotide is still not functional. What is the most likely cause?

The most common cause is endosomal trapping. Cell-penetrating peptides are highly efficient at getting cargo into cells but often fail to release it from endosomes into the cytoplasm, where most oligonucleotides need to act. To confirm this, perform a colocalization experiment with an endosomal marker. To overcome this, you can explore strategies to promote endosomal escape. One promising method is Photochemical Internalization (PCI), which uses light to trigger the rupture of endosomal membranes and has been shown to increase functional delivery by over 90% with certain CPPs [5].

Q4: What critical quality attributes (CQAs) should we monitor for oligonucleotide stability during formulation development?

Beyond standard identity and purity assays, you should closely monitor:

- Diastereomeric Composition: PS linkages create diastereomers, which can have different properties [2].

- Impurity Profile: Identify and quantify key impurities like (n-1) truncations and depurination products [2].

- For AAV-delivered DNA: DNA integrity is a crucial CQA, as encapsidated DNA can degrade via pH-dependent depurination (acidic pH) or ejection (basic pH), leading to potency loss [6] [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Oligonucleotide Stability in Serum

Objective: To determine the half-life of an oligonucleotide in a biologically relevant nuclease-containing environment.

Materials:

- Oligonucleotide of interest (e.g., 20-mer ASO)

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS)

- Nuclease-Free Water

- 10X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0

- Heating block or water bath set to 37°C

- Proteinase K

- Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1)

- Equipment for HPLC or Capillary Gel Electrophoresis (CGE)

Method:

- Preparation: Dilute the oligonucleotide in nuclease-free water to a stock concentration of 100 µM. Pre-warm FBS to 37°C.

- Incubation Setup: In a microcentrifuge tube, create a reaction mixture containing 90% (v/v) FBS and 10% (v/v) oligonucleotide stock (final oligonucleotide concentration: 10 µM). Mix thoroughly and place immediately in the 37°C heating block.

- Time Points: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 24 h), remove a 20 µL aliquot from the mixture.

- Reaction Termination: Immediately add 2 µL of 0.5 M EDTA to the aliquot to chelate divalent cations and inhibit nuclease activity. Place on ice.

- Digestion and Extraction:

- Add 2 µL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL) to the aliquot and incubate at 50°C for 1 hour to digest serum proteins.

- Add an equal volume of Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol, vortex vigorously, and centrifuge at top speed for 5 minutes.

- Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube.

- Analysis: Analyze the extracted oligonucleotide using HPLC or CGE. Quantify the percentage of full-length oligonucleotide remaining at each time point.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural log of the % full-length oligonucleotide against time. The slope of the linear fit is -k (degradation rate constant). The half-life (t1/2) is calculated as ln(2)/k.

Protocol 2: Assessing Functional Delivery via Photochemical Internalization (PCI)

Objective: To enhance the functional endosomal escape of a CPP-complexed oligonucleotide using light-triggered membrane disruption [5].

Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., HeLa, MDA-MB-231)

- Cell culture media and reagents

- CPP (e.g., tri-cTatB peptide [5])

- Oligonucleotide (e.g., siRNA against GAPDH or PLK1)

- Photosensitizer (e.g., disulfonated tetraphenyl chlorin, TPCS2a)

- Light source for illumination (e.g., LumiSource lamp)

- Opti-MEM or serum-free medium

- Materials for downstream functional assay (e.g., qPCR primers, Western blot antibodies)

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in a 24-well or 96-well plate at an appropriate density and incubate for 24 hours to reach ~70% confluency.

- Photosensitizer Incubation: Add the photosensitizer (e.g., 0.2 µg/mL TPCS2a) to the cell culture medium and incubate for 18 hours. Include control wells without photosensitizer.

- Complex Formation: While cells are incubating with the photosensitizer, prepare complexes of the CPP and oligonucleotide in Opti-MEM. A typical mass ratio of 1:1 (CPP:Oligo) can be used. Incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature to allow complex formation.

- Complex Transfection:

- After the 18-hour incubation, carefully wash the cells twice with PBS to remove unincorporated photosensitizer.

- Add the CPP/oligonucleotide complexes to the cells in fresh, serum-free medium.

- Incubate for 4 hours to allow for cellular uptake.

- Light Illumination:

- After the 4-hour transfection, wash the cells once with PBS and add fresh, complete medium.

- Expose the cells to light from the LumiSource lamp (e.g., blue or red light depending on the photosensitizer) for a specific duration (e.g., 30-180 seconds). Keep control plates in the dark.

- Post-Illumination Incubation: Return all plates to the incubator and culture for an additional 44-48 hours to allow for gene expression changes.

- Functional Analysis: Harvest cells and assess the functional outcome of the oligonucleotide delivery.

- For siRNA: Measure mRNA levels by qRT-PCR or protein levels by Western blot for the target gene (e.g., GAPDH).

- Compare the knockdown efficiency in the "Light" group versus the "No Light" and "No Oligo" control groups.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

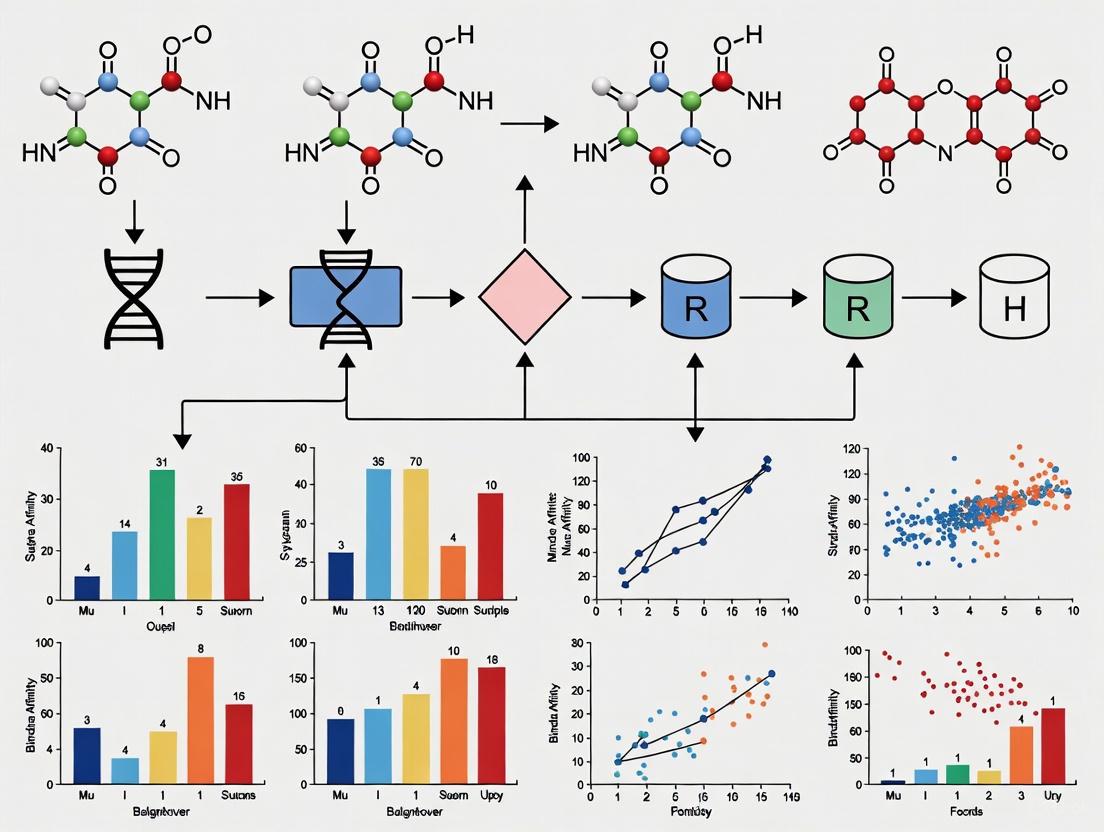

Oligonucleotide Intracellular Trafficking

This diagram illustrates the major pathways and bottlenecks an oligonucleotide faces after administration, from circulation to target engagement.

Photochemical Internalization (PCI) Workflow

This flowchart details the experimental steps for implementing PCI to enhance endosomal escape, as described in the protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Addressing Core Challenges |

|---|---|

| Phosphoramidites (2'-MOE, 2'-F, LNA) | Chemically modified building blocks for oligonucleotide synthesis that enhance nuclease resistance and binding affinity [3] [1]. |

| Phosphorothioate (PS) Linkages | Backbone modifications where a sulfur atom replaces a non-bridging oxygen, drastically increasing resistance to nuclease degradation and improving pharmacokinetics [3] [1]. |

| N-Acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) | A targeting ligand conjugated to oligonucleotides (especially siRNAs) that enables highly efficient uptake by hepatocytes via the asialoglycoprotein receptor, solving liver-specific delivery [3] [1]. |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) | Short peptides (e.g., tri-cTatB) that facilitate cellular internalization of complexed oligonucleotides, overcoming the poor permeability of the cellular membrane [5]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Advanced delivery vehicles that encapsulate oligonucleotides, protecting them from nucleases and promoting cellular uptake through endocytosis [3]. |

| Photosensitizers (e.g., TPCS₂a) | Molecules used in Photochemical Internalization (PCI) that, upon light activation, generate reactive oxygen species to disrupt endosomal membranes, promoting endosomal escape [5]. |

| Capillary Gel Electrophoresis (CGE) | An analytical technique used for high-resolution separation and quantification of full-length oligonucleotides from truncated impurities, essential for stability testing and quality control [6] [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary function of the phosphorothioate (PS) backbone modification in first-generation oligonucleotides? The phosphorothioate (PS) backbone modification, in which a sulfur atom replaces one of the non-bridging oxygen atoms in the phosphate group, serves two primary functions [8]:

- Nuclease Resistance: It protects the oligonucleotide from degradation by nucleases, thereby increasing its stability in biological environments.

- Improved Pharmacokinetics: It enhances the binding of oligonucleotides to plasma proteins, which reduces renal excretion and increases half-life, improving tissue distribution and cellular uptake [8].

Q2: What are the main limitations of fully phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides (first-generation) that led to the development of newer chemistries? While PS modifications provided a crucial foundation, first-generation ASOs (fully PS-modified DNA) had several key limitations [8]:

- Reduced Binding Affinity: PS modifications decrease the oligonucleotide's affinity for its complementary RNA target.

- High Dose Requirements: Early clinical trials required repeated administration of high doses, leading to toxicity concerns and limited efficacy.

- Protein Binding-Mediated Toxicity: Nonspecific binding to proteins was associated with certain toxicities, including immune stimulation and thrombocytopenia.

Q3: My fully PS-modified antisense oligonucleotide shows poor target engagement in vitro. What could be the reason? Poor target engagement can stem from the inherently lower binding affinity of the PS DNA backbone for its RNA target compared to an unmodified phosphodiester backbone [8]. Furthermore, the specific sequence might be prone to forming self-dimers or secondary structures that hinder hybridization. To troubleshoot:

- Check Sequence Design: Use predictive software to analyze secondary structure and self-complementarity.

- Consider a Gapmer Design: Move away from the fully PS-modified first-generation design. Incorporate high-affinity sugar modifications (like 2'-MOE or LNA) in the flanks while retaining a central PS DNA "gap" to enable RNase H activity [8].

- Verify Purity: Use analytical techniques like ion-exchange chromatography or capillary electrophoresis to ensure the product is not compromised by truncated sequences or impurities [9].

Q4: What analytical techniques are critical for characterizing and troubleshooting the purity and stability of PS-modified oligonucleotides? The complex impurity profiles of synthetic oligonucleotides necessitate robust analytical methods [9] [10]. Key techniques include:

- Anion-Exchange Chromatography (AEX): Separates oligonucleotides based on charge (length and modification level), ideal for resolving PS-backbone impurities.

- Reversed-Phase Chromatography (RP-HPLC): Useful for separating oligonucleotides with hydrophobic tags (like the 5'-DMT group) or certain conjugates.

- Capillary Electrophoresis (CE): Provides high-resolution separation based on size and charge, excellent for detecting length-based impurities.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Essential for confirming identity, detecting modifications, and characterizing degradation products.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Phosphorothioate-Modified Oligonucleotide via Solid-Phase Phosphoramidite Chemistry

This is the industry-standard method for synthesizing PS-modified oligonucleotides [11].

Principle: Nucleoside phosphoramidites are sequentially added to a growing oligonucleotide chain attached to a solid support (e.g., controlled-pore glass or polystyrene). The key step for PS incorporation is the sulfurization of the phosphite triester linkage [11].

Materials:

- Solid Support: CPG or polystyrene with the first nucleoside attached.

- Phosphoramidites: Protected nucleoside phosphoramidite monomers (e.g., DMT-protected 5'-OH).

- Activator Solution: An acidic azole catalyst (e.g., 1H-tetrazole) to activate the phosphoramidite.

- Oxidizing/Sulfurizing Reagent: For PS backbone, a sulfur transfer reagent (e.g., DDTT, PADS) is used instead of an iodine-based oxidizer.

- Capping Reagents: A mixture of acetic anhydride and 1-methylimidazole to cap unreacted chains.

- Detritylation Reagent: An acid (e.g., dichloroacetic acid in toluene) to remove the 5'-DMT protecting group.

Procedure:

- Detritylation: Flush the column with dichloroacetic acid in toluene to remove the 5'-DMT group from the support-bound nucleoside, freeing the 5'-OH for coupling.

- Coupling: Deliver the desired phosphoramidite and activator solution to the column. The activated phosphoramidite couples to the free 5'-OH group, forming a phosphite triester linkage.

- Sulfurization: Flush the column with the sulfurizing reagent (e.g., DDTT solution). This replaces one oxygen atom in the phosphite group with sulfur, creating a phosphorothioate linkage.

- Capping: Introduce the capping reagents to acetylate any unreacted 5'-OH groups (~1-2% per cycle), preventing them from elongating in subsequent cycles and forming deletion sequences.

- Washing: Wash the support with solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) between each step to remove excess reagents.

- Cycle Repetition: Repeat steps 1-5 for each subsequent nucleotide in the sequence.

- Cleavage and Deprotection: After full sequence assembly, treat the support with concentrated ammonium hydroxide at elevated temperature. This cleaves the oligonucleotide from the support and removes base-labile protecting groups (e.g., benzoyl from adenine, cytosine).

Protocol 2: Purification of Crude PS-Modified Oligonucleotides by Anion-Exchange Chromatography

Principle: AEX chromatography separates oligonucleotides based on their negative charge, which is proportional to length and the number of PS groups. This effectively resolves the full-length product from shorter failure sequences [11].

Materials:

- Stationary Phase: Quaternary ammonium-functionalized resin (e.g., Dionex DNAPac or similar).

- Mobile Phase A: Low-salt buffer (e.g., 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8).

- Mobile Phase B: High-salt buffer (e.g., 20 mM sodium phosphate, 1.0 M NaClO4, pH 8).

- HPLC System: Equipped with a UV detector (λ = 260 nm).

- Preparative AEX column.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the crude oligonucleotide solution obtained after cleavage/deprotection in Mobile Phase A and filter.

- Chromatographic Run:

- Load the sample onto the equilibrated AEX column.

- Elute using a linear gradient from 0% to 100% Mobile Phase B over 30-60 minutes.

- Monitor the UV trace at 260 nm.

- Fraction Collection: The full-length product will elute at a higher salt concentration than shorter failure sequences. Collect the peak corresponding to the full-length product.

- Desalting: Desalt the collected fraction using tangential flow filtration (TFF) or ethanol precipitation.

- Lyophilization: Isolate the purified oligonucleotide as a solid by lyophilization.

Table 1: Impact of Chemical Modifications on Oligonucleotide Properties [8]

| Modification Type | Key Feature | Impact on Binding Affinity (ΔTm/mod) | Primary Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorothioate (PS) | Sulfur substitution in backbone | Slight decrease | Nuclease stability, improved PK/PD (protein binding) |

| 2'-O-Methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) | 2'-O-methoxyethyl ribose | +0.9°C to +1.7°C | Nuclease resistance, increased binding affinity |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) | Bridged 2'-O and 4'-C | +4.0°C to +8.0°C | Very high binding affinity, allows for shorter ASOs |

| Constrained Ethyl (cEt) | Methylated LNA analog | Similar to LNA | Very high binding affinity, improved potency |

Table 2: Common Analytical Techniques for PS-Modified Oligonucleotide Quality Control [9]

| Technique | Separation Principle | Best Suited for Detecting |

|---|---|---|

| Anion-Exchange Chromatography (AEX) | Charge (length/backbone) | Failure sequences (n-1, n-2), backbone impurity profiles |

| Reversed-Phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) | Hydrophobicity | DMT-on vs. DMT-off impurities, certain conjugates |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | Size/Charge | Short and long sequence variants, stereoisomer separation |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Workflow for Synthesis and QC of PS-Modified Oligonucleotides.

Diagram 2: Legacy and Evolution from First-Generation PS-Modified Oligonucleotides.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for PS-Oligonucleotide Work

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside Phosphoramidites | Building blocks for synthesis | DMT-protected 5'-OH, appropriate base protection (e.g., Bz for A, C). |

| Solid Support (CPG/Polystyrene) | Matrix for chain assembly | Pore size, loading capacity, compatibility with UnyLinker for milder cleavage. |

| Sulfurizing Reagent (e.g., DDTT) | Converts phosphite to PS linkage | Efficiency, stability, and byproduct formation. Newer reagents offer faster reaction times. |

| Anion-Exchange Resins | Purification of crude product | Resolution, capacity, and recovery for full-length PS-oligonucleotides. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) | Desalting and concentration | Membrane molecular weight cutoff (MWCO), scalability, and yield. |

Technical Support Center

This support center provides troubleshooting and FAQs for researchers working with 2'OMe, 2'F, and LNA-modified oligonucleotides, framed within the thesis of enhancing oligonucleotide stability and binding affinity for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Solubility or Aqueous Buffer Compatibility

- Problem: Oligonucleotide precipitates or forms aggregates upon resuspension.

- Cause: High levels of hydrophobic bases or long sequences can reduce solubility, especially in LNA-rich designs.

- Solution:

- Resuspend in a small volume of nuclease-free water, then dilute to the final desired concentration with the appropriate buffer.

- Heat the oligo at 55-65°C for 1-5 minutes, then vortex thoroughly.

- For problematic LNA oligos, consider adding a 5' or 3' hydrophilic spacer (e.g., hexa-ethyleneglycol) during synthesis.

Issue 2: Reduced PCR Efficiency or Specificity

- Problem: LNA-modified primers yield no product, non-specific bands, or lower yield.

- Cause: Excessively high melting temperature (Tm) leading to mis-priming or inefficient enzyme binding.

- Solution:

- Redesign Primer: Follow the rule of thumb: for a standard 18-24 bp primer, incorporate 3-5 LNA monomers and avoid placing them at the 3'-end.

- Optimize Protocol: Increase annealing temperature in a gradient PCR. Adjust Mg²⁺ concentration.

- Use a DNA polymerase specifically validated for modified nucleotides.

Issue 3: Inconsistent or Weak In Situ Hybridization Signal

- Problem: Faint or patchy signal in fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) experiments using 2'OMe or 2'F RNA probes.

- Cause: Inefficient penetration into the fixed tissue or cells; suboptimal hybridization stringency.

- Solution:

- Permeabilization: Titrate the concentration and time of permeabilization agents (e.g., Triton X-100, pepsin).

- Hybridization Buffer: Ensure the buffer contains denaturants (e.g., formamide) and salts to control stringency.

- Wash Stringency: Increase wash temperature and/or decrease salt concentration in wash buffers to reduce background.

Issue 4: Unexpected Toxicity or Cellular Stress in Cell Culture

- Problem: Cell death or altered morphology observed after transfection of modified oligonucleotides.

- Cause: Non-specific immune activation (e.g., by certain sequences) or chemical toxicity from impurities.

- Solution:

- HPLC Purification: Ensure oligonucleotides are purified via Reverse-Phase or Ion-Exchange HPLC to remove truncated failure sequences and organic salts.

- Sequence Check: Screen sequences for potential immunostimulatory motifs using specialized software.

- Dose Titration: Perform a careful dose-response curve to find the minimal effective dose.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which modification offers the highest binding affinity (Tm increase) for my antisense oligonucleotide? A: LNA provides the most significant per-modification increase in Tm (+2 to +8 °C per monomer). 2'F provides a moderate increase (+1.5 to +3 °C per monomer), while 2'OMe offers a smaller increase (+0.5 to +1.5 °C per monomer). The choice depends on the balance between affinity, nuclease resistance, and cost.

Q2: How do I choose between 2'OMe, 2'F, and LNA for nuclease resistance? A: All three confer high nuclease resistance compared to DNA or RNA. 2'F is generally considered the most resistant to nucleases, followed by LNA and then 2'OMe. For in vivo applications where serum stability is paramount, 2'F modifications are often preferred in the "gapmer" design.

Q3: What is the recommended maximum number of consecutive LNA monomers? A: Avoid stretches of more than 4-5 consecutive LNAs. Long LNA stretches can lead to severe off-target binding due to excessive affinity and may also increase the risk of solubility issues and non-specific toxicity.

Q4: Can these modifications be used in CRISPR guide RNAs? A: Yes. 2'OMe and 2'F modifications, particularly at the 5' and 3' ends of sgRNA, are widely used to protect against exonucleases and reduce immune responses without significantly compromising Cas9 cleavage activity. LNA is less common in this context.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Oligonucleotide Modifications

| Property | DNA (Control) | 2'-O-Methyl (2'OMe) | 2'-Fluoro (2'F) | Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tm Increase/Mod. | Baseline | +0.5 to +1.5 °C | +1.5 to +3.0 °C | +2.0 to +8.0 °C |

| Nuclease Resistance | Low | High | Very High | High |

| RNAse H Recruitment | Yes | No | No | No |

| Synthesis Cost | Low | Moderate | Moderate-High | High |

| Toxicity/Immunogenicity | Low | Low | Low | Moderate (sequence-dependent) |

| Primary Backbone | Phosphodiester | Phosphodiester | Phosphodiester | Phosphodiester |

Table 2: Recommended Application-Based Modification Strategies

| Application | Recommended Modifications | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Antisense (RNAse H) | Gapmer: LNA/2'OMe wings, DNA gap | Wings provide affinity & stability; DNA gap allows RNAse H cleavage. |

| siRNA (Passenger Strand) | 2'OMe or 2'F on passenger strand | Blocks RISC loading, enhances nuclease resistance, reduces off-targets. |

| Antagomirs / miRNA Inhibitors | Full LNA or LNA/DNA mix | Maximizes affinity and in vivo stability for target sequestration. |

| FISH Probes | 2'OMe, 2'F RNA, or LNA | Increases brightness and specificity of hybridization signal. |

| PCR Primers/Probes | LNA at critical positions | Increases specificity and allows for shorter primer/probe design. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Melting Temperature (Tm) for Modified Duplexes

Objective: To quantify the binding affinity enhancement provided by 2'OMe, 2'F, or LNA modifications.

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute the complementary strands (modified and unmodified) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 10 mM Sodium Phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0).

- Mix strands in a 1:1 ratio. The final concentration of each strand should be 2-4 µM.

- Denature at 95°C for 5 minutes and slowly cool to room temperature to anneal.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy:

- Load the annealed duplex into a quartz cuvette in a spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature controller.

- Set the method to monitor absorbance at 260 nm while ramping the temperature from 25°C to 95°C at a rate of 0.5°C/min.

Data Analysis:

- Plot absorbance (A260) vs. Temperature. The Tm is the temperature at the midpoint of the melting transition (where 50% of the duplex is dissociated).

- Compare the Tm of the modified duplex with the unmodified control.

Protocol 2: Serum Stability Assay

Objective: To evaluate the resistance of modified oligonucleotides to nucleases in biological fluids.

Incubation Setup:

- Dilute the oligonucleotide (2-5 µg) in 90 µL of nuclease-free buffer.

- Add 10 µL of fetal bovine serum (FBS) to start the reaction. Incubate at 37°C.

- Prepare a T=0 control by adding serum after the reaction is stopped.

Sampling:

- Withdraw 15 µL aliquots at time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- Immediately mix each aliquot with 15 µL of formamide/EDTA loading dye and heat at 95°C for 5 minutes to denature proteins and stop the reaction.

Analysis:

- Load samples onto a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (15-20%) or analyze by capillary electrophoresis.

- Visualize and quantify the intact full-length oligonucleotide band. Plot % full-length remaining vs. time to determine the half-life.

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Oligo Mod Stability Workflow

Diagram 2: Gapmer Design Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| HPLC-Purified Oligos | Essential for obtaining high-purity, full-length modified oligonucleotides free from failure sequences that can confound results. |

| Nuclease-Free Water/Buffers | Prevents degradation of oligonucleotides during storage and experimental setup. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Used in serum stability assays as a source of nucleases to simulate in vivo degradation. |

| Transfection Reagent | For delivering charged, modified oligonucleotides into cells; must be compatible with the oligo chemistry. |

| Denaturing PAGE Gel Kit | For analyzing oligonucleotide integrity and length after synthesis or stability assays. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | For accurately quantifying oligonucleotide concentration and performing Tm analysis. |

| Thermocycler with Gradient | Crucial for optimizing annealing temperatures in PCR or hybridization assays using high-Tm LNA primers/probes. |

FAQ: Resolving Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My oligonucleotides show rapid degradation in serum. How can backbone modifications improve nuclease resistance?

Rapid degradation is often due to the unmodified phosphodiester (PO) backbone being recognized by nucleases. Incorporating phosphorothioate (PS) linkages, where a non-bridging oxygen is replaced with sulfur, is a primary strategy to enhance stability [12]. PS modifications increase resistance to nuclease digestion and improve pharmacokinetics by enhancing binding to serum proteins [12]. For further stability, combine PS backbones with 2'-ribose modifications (e.g., 2'-O-Methyl, 2'-Fluoro, 2'-MOE) which also improve affinity for complementary RNA targets [12].

Q2: How do I address poor cellular uptake of my therapeutic oligonucleotides?

The polyanionic nature of oligonucleotides hinders cell membrane crossing. Solution strategies include:

- Backbone Modifications: Incorporate phosphorothioate (PS) linkages in the backbone. This not only improves stability but also enhances cellular association and uptake, partly by increasing protein binding [12].

- Bioconjugation: Covalently link oligonucleotides to targeting ligands. A prominent example is GalNAc conjugation for targeted delivery to hepatocytes via the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR), which has led to multiple approved therapies [13]. Other options include lipid or peptide conjugates to improve membrane interaction and uptake [13].

- Nanoparticle Formulation: Encapsulate oligonucleotides in Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) or other carrier systems to protect them and facilitate endocytosis [14].

Q3: What are the critical analytical challenges for characterizing modified oligonucleotides, and how can they be overcome?

Modified oligonucleotides present unique analytical hurdles due to their high molecular weight, complex impurity profiles, and the presence of diastereomers (e.g., from PS linkages) [15] [2].

- Challenge: Resolving near-isobaric impurities (differing by ±1 Da) and truncated sequences.

- Solution: Use advanced liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Careful selection of ion-pairing reagents in chromatography is critical to achieve the necessary peak resolution [15].

- Challenge: Characterizing the diastereomeric composition of phosphorothioate-linked oligonucleotides.

- Solution: While stereopure synthesis is an area of active research, current analytical methods often focus on monitoring consistency in manufacturing rather than fully characterizing all diastereomers due to the vast number of possible variants [15].

Q4: My oligonucleotide candidate exhibits unexpected cellular toxicity. What are potential causes related to chemical modifications?

Toxicity can arise from several modification-related factors:

- Protein Interactions: Phosphorothioate (PS) linkages can, in some cases, lead to cellular toxicity by interacting with cellular proteins beyond the intended target (e.g., RNase H1 or paraspeckle proteins), potentially altering their localization and function [12].

- Mitigation Strategy: Tailoring the chemical design, such as incorporating 2'-ribose modifications, can help reduce these off-target protein interactions and associated toxicities [12].

- Immunogenicity: Unmodified nucleic acids can provoke immune responses; however, chemical modifications like 2'-ribose modifications and PS linkages generally help mitigate this risk [12].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Backbone-Modified Oligonucleotides

Protocol: Assessing Nuclease Stability via LC-MS

Objective: To evaluate the resistance of a backbone-modified oligonucleotide to nuclease degradation compared to an unmodified control.

Materials:

- Test oligonucleotides (modified and unmodified control)

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) or specific nucleases (e.g., S1 Nuclease, DNase I)

- Incubation buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-HCl)

- Heating block or water bath

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) system

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) cartridges for sample cleanup

Method:

- Preparation: Dilute oligonucleotides in an appropriate incubation buffer to a final concentration of 1-10 µM.

- Incubation: Add 20% (v/v) FBS to the oligonucleotide solution. Mix gently and incubate at 37°C.

- Sampling: Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- Reaction Termination: Immediately heat samples to 95°C for 5 minutes to denature enzymes, or add a chelating agent like EDTA if using metal-dependent nucleases.

- Sample Cleanup: Purify samples using SPE to remove proteins and salts that interfere with LC-MS analysis.

- Analysis: Inject cleaned samples into the LC-MS system.

- Use ion-pair reversed-phase chromatography for separation.

- Monitor the intact mass of the parent oligonucleotide and identify metabolite peaks corresponding to truncated sequences.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of intact oligonucleotide remaining at each time point. Plot the degradation curve and determine the half-life.

Protocol: Measuring Binding Affinity Using Melting Temperature (Tm) Analysis

Objective: To determine the change in melting temperature (ΔTm) conferred by a backbone modification, indicating its effect on binding affinity to a complementary RNA strand.

Materials:

- Modified oligonucleotide and unmodified control

- Complementary RNA target strand

- Buffer (commonly 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate buffer, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with a temperature-controlled Peltier cell

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Combine the oligonucleotide and its complementary RNA target in a 1:1 ratio in buffer. Use a concentration where the absorbance falls within the linear range of the instrument (typically 2-4 µM).

- Denaturation and Renaturation: Heat the sample to 90°C for 5 minutes and then cool slowly to room temperature to ensure proper duplex formation.

- Tm Run: Place the sample in a quartz cuvette in the spectrophotometer. Set the program to cool from 80°C to 20°C at a slow rate (e.g., 0.5°C per minute).

- Data Collection: Monitor the UV absorbance at 260 nm. As the temperature decreases and the duplex forms, the absorbance (hyperchromicity) will decrease.

- Data Analysis: Plot the absorbance against temperature. The melting temperature (Tm) is defined as the temperature at which 50% of the duplex is dissociated, corresponding to the midpoint of the transition curve in the first derivative of the plot. A higher Tm for the modified oligonucleotide indicates increased binding affinity.

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Oligonucleotide Mechanism of Action

Backbone Modification Development Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Oligonucleotide Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphoramidites (e.g., 2'-O-Me, 2'-F, LNA) | Chemical building blocks for solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis. Introduce modifications primarily at the 2'-sugar position to enhance nuclease resistance and binding affinity [12]. | Purity is critical for synthesis efficiency. Chiral phosphoramidites are needed for stereopure PS synthesis. |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents (e.g., HFIP, TEA) | Critical mobile phase components in Reversed-Phase LC-MS analysis. Enable separation and purification of oligonucleotides from complex mixtures and impurities [15]. | Selection and concentration dramatically impact peak shape, resolution, and sensitivity for detecting impurities. |

| GalNAc Conjugation Reagents | Enable targeted delivery of oligonucleotides to hepatocytes. Linkage to sugars like N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) facilitates uptake via the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) [13]. | Conjugation chemistry must be efficient and not impair oligonucleotide activity. A well-established strategy for liver targets. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery platform for encapsulating oligonucleotides (especially siRNA). Protects from degradation, improves pharmacokinetics, and facilitates cellular uptake via endocytosis [14]. | Composition (ionizable lipid, PEG-lipid, etc.) must be optimized for efficacy, stability, and tolerability. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Sample cleanup prior to analysis (e.g., LC-MS). Remove salts, proteins, and other contaminants from biological samples (serum, tissue homogenates) [13]. | Selection of sorbent chemistry is key for high recovery of the specific oligonucleotide. |

Quantitative Data on Oligonucleotide Modifications

Table: Impact of Common Chemical Modifications on Oligonucleotide Properties

| Modification Type | Location | Key Functional Benefits | Potential Drawbacks / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorothioate (PS) | Backbone (non-bridging oxygen) | Increased nuclease resistance, improved pharmacokinetics (PK), enhanced cellular uptake [12]. | Introduction of chirality (diastereomers), potential for off-target protein interactions and toxicity [12]. |

| 2'-O-Methyl (2'-O-Me) | Sugar (2' position) | Enhanced nuclease resistance, increased binding affinity (ΔTm ~ +1.5 to +2.0 °C per mod), reduced immunogenicity [12]. | Not compatible with RNase H1 activation in the modified region [12]. |

| 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) | Sugar (2' position) | Strong nuclease resistance, high binding affinity (ΔTm ~ +2.0 to +2.5 °C per mod) [12]. | Not compatible with RNase H1 activation in the modified region [12]. |

| 2'-O-Methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) | Sugar (2' position) | Very high binding affinity (ΔTm ~ +2.0 to +3.0 °C per mod), strong nuclease resistance [12]. | Not compatible with RNase H1 activation in the modified region [12]. |

| GalNAc Conjugation | Terminal (3' or 5' end) | Enables potent receptor-mediated uptake into hepatocytes, dramatically improving potency for liver targets (>10-fold increase), allows for subcutaneous administration with extended duration [13]. | Primarily effective for liver targets; limited utility for extra-hepatic tissues. |

The Impact of Modifications on Pharmacokinetics and Specificity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do chemical modifications improve the stability of therapeutic oligonucleotides? Chemical modifications enhance oligonucleotide stability by protecting them from degradation by nucleases, which are abundant in biological systems. The most common stability-inducing modifications include:

- Phosphorothioate (PS) Backbone: Replaces a non-bridging oxygen atom in the phosphate backbone with sulfur. This increases resistance to nucleases and improves binding to plasma proteins, which reduces renal clearance and increases tissue bioavailability [16] [17].

- Sugar Modifications (2'-substituents): Incorporating groups like 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), or 2'-fluoro (2'-F) at the sugar moiety alters the sugar conformation, increasing nuclease resistance and enhancing binding affinity to the target RNA [8] [16].

- Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA): This modification locks the sugar into a rigid C3'-endo conformation, leading to a significant increase in target affinity (ΔTm of +4°C to +8°C per modification) and metabolic stability [8] [16].

Q2: What is the impact of plasma protein binding on oligonucleotide pharmacokinetics? Plasma protein binding is a critical factor that shapes the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of oligonucleotides [18].

- For PS-modified ASOs: High binding to plasma proteins like albumin limits glomerular filtration, reducing renal excretion and increasing the drug's half-life in circulation. This protein binding provides a reservoir effect, facilitating broader tissue distribution, particularly to the liver, kidney, spleen, and lymph nodes [17] [18].

- For Hydrophilic Modifications (e.g., PMO): Oligonucleotides like Phosphorodiamidate Morpholino Oligomers (PMOs) have lower plasma protein binding (around or below 40%), leading to higher renal clearance and different distribution patterns [18].

Q3: How do modifications influence the specificity of therapeutic oligonucleotides? Modifications can be strategically used to fine-tune specificity and minimize off-target effects:

- High-Affinity Modifications and Toxicity: Gapmer ASOs using high-affinity modifications like LNA can sometimes cause hepatotoxicity by directing off-target RNase H cleavage of mismatched transcripts. This risk is sequence-dependent and can be mitigated through careful sequence design and computational tools to minimize complementarity to off-target RNAs [8].

- Sugar Modifications: Modifications like 2'-O-methyl not only improve stability and affinity but can also help reduce immune stimulation, thereby increasing the therapeutic window and specificity of action [8].

Q4: What are the key formulation and handling practices for modified oligonucleotides? Proper handling is essential to maintain the integrity and activity of oligonucleotides [19]:

- Storage: For long-term stability, store oligonucleotides dry at -20°C. When in solution, resuspend in a neutral buffer like TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and store at -20°C in aliquots to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [19].

- Light-Sensitive Modifications: Oligonucleotides conjugated with fluorescent dyes (e.g., Cy3, FAM) are light-sensitive. They must be stored in the dark at -20°C, and the reconstitution buffer pH should be adjusted accordingly (e.g., pH 7.0-7.5 for Cy dyes) to prevent dye degradation [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Efficacy of Oligonucleotide In Vivo

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid degradation in serum | Perform serum stability assay (see Protocol below). Analyze degradation fragments via gel electrophoresis [20]. | Incorporate stabilizing modifications (e.g., 2'-OMe, 2'-MOE, 2'-F, PS backbone, LNA) based on stability assay results [8] [20]. |

| Insufficient tissue uptake | Evaluate biodistribution pattern in preclinical models. Measure tissue concentrations [17] [18]. | Consider conjugating a targeting ligand (e.g., GalNAc for hepatocyte targeting) to enhance cellular uptake in the target tissue [8]. |

| Inadequate plasma half-life | Determine PK parameters (half-life, clearance) from plasma concentration-time data [17] [18]. | Optimize plasma protein binding by using PS modifications or lipophilic conjugates to reduce renal clearance and increase systemic exposure [17] [18]. |

Problem 2: Undesired Toxicity or Off-Target Effects

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence-dependent off-target RNA cleavage | Use bioinformatics tools to screen for complementary sequences in the transcriptome, particularly intronic regions [8]. | Redesign the oligonucleotide sequence to minimize complementarity to off-target transcripts. Avoid "seed" regions with high propensity for mismatch hybridization [8]. |

| Overly high affinity leading to non-specific binding | Evaluate specificity using microarray or RNA-Seq analysis. | Use a chimeric design (e.g., gapmer) that balances high-affinity flanking regions with a central DNA gap for RNase H activity, or consider lower-affinity modifications [8]. |

| Excessive accumulation in non-target tissues | Conduct quantitative whole-body biodistribution studies [17] [18]. | Adjust the chemical architecture (e.g., reducing PS content) or employ a tissue-specific targeting ligand to redirect the oligonucleotide away from sites of toxicity [8] [18]. |

Quantitative Data on Modifications

Table 1: Impact of Common Sugar Modifications on Oligonucleotide Properties [8]

| Modification | Binding Affinity (ΔTm/modification) | Key Properties and Clinical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 2'-O-Methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) | +0.9°C to +1.7°C | Improved nuclease resistance. Used in Mipomersen and Nusinersen [8]. |

| 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) | ~ +2.5°C | High binding affinity, good nuclease resistance [8]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) | +4°C to +8°C | Very high affinity and stability. Requires careful sequence design to avoid toxicity [8]. |

| Constrained Ethyl (cEt) | Similar to LNA | High affinity, often used in chimeric gapmer designs [8]. |

Table 2: Pharmacokinetic Differences Driven by Oligonucleotide Chemistry [17] [18]

| Property | Phosphorothioate (PS) ASOs (e.g., Inotersen) | Phosphorodiamidate Morpholino (PMO) (e.g., Eteplirsen) |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma Protein Binding | High (>90%) | Low (around or below 40%) [18]. |

| Primary Clearance Route | Metabolism by nucleases, limited renal clearance | Predominantly renal excretion [18]. |

| Tissue Bioavailability | High (often >90% of dose), broad systemic distribution | Lower, more restricted distribution [17] [18]. |

| Tissues with Highest Uptake | Liver, kidney, bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen [17]. | Varies, but generally lower non-specific tissue accumulation [18]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Serum Stability Assay for Oligonucleotides

Background: This protocol assesses the resistance of oligonucleotides to nuclease degradation in serum, a critical step in predicting in vivo stability [20].

Graphical Overview of Workflow:

Materials and Reagents [20]:

- Oligonucleotides: Modified or unmodified sense and antisense strands.

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS): Source of nucleases.

- 10× Annealing Buffer: 100 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5-8.0.

- Nuclease-free water.

- Equipment: Dry block heater, gel electrophoresis apparatus, UV transilluminator or imaging system.

Step-by-Step Methodology [20]:

- Oligo Duplex Preparation:

- Resuspend single-stranded oligos to a high concentration (e.g., 200 µM) in nuclease-free water.

- Combine equal amounts of sense and antisense strands with 10× annealing buffer.

- Incubate the mixture for 5 minutes at 95°C, then allow it to cool slowly to room temperature to form the duplex.

- Serum Incubation:

- Dilute the prepared duplex in FBS to a final concentration suitable for detection (e.g., 1-5 µM).

- Incubate the mixture at 37°C.

- Remove aliquots (e.g., 5 µL) at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours). Immediately freeze aliquots or proceed to analysis to stop the reaction.

- Sample Analysis:

- Analyze the aliquots using gel electrophoresis (e.g., polyacrylamide or agarose gel).

- Stain the gel with a nucleic acid stain (e.g., GelRed) and visualize under UV light.

- Use software like ImageJ to quantify the band intensity of the intact oligonucleotide duplex over time.

Data Interpretation:

- Plot the percentage of intact oligonucleotide remaining versus time to determine the degradation half-life.

- Compare the degradation kinetics of differently modified oligonucleotides to rank their relative stabilities. A slower rate of degradation indicates a more stable oligonucleotide construct.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Oligonucleotide Stability and PK Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Modified Oligonucleotides | The test articles for evaluating the impact of chemistry on stability, PK, and efficacy [8] [20]. | Include a panel of oligos with different modifications (PS, 2'-OMe, LNA, etc.) and a fully unmodified control for comparison. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Provides a complex mixture of nucleases for in vitro stability testing, simulating the in vivo circulatory environment [20]. | Use the same batch of FBS across an experiment for consistency due to potential lot-to-lay variability in nuclease activity. |

| Gel Electrophoresis System | Separates and visualizes intact oligonucleotides from their degradation fragments [20]. | Glycerol-tolerant polyacrylamide gels can provide better resolution for analyzing complex samples from serum incubations [20]. |

| Ultrafiltration Devices | Used to separate plasma protein-bound oligonucleotides from unbound (free) oligonucleotides for protein binding studies [18]. | Must pre-treat devices with detergent (e.g., Tween-20) and use low-adsorption plates to minimize non-specific binding of oligos. |

| TE Buffer (pH 7.0-8.0) | Standard buffer for resuspending and storing oligonucleotides; the EDTA chelates metal ions to inhibit metal-catalyzed degradation [19]. | Adjust pH based on modifications: use pH 7.0-7.5 for Cy dyes and pH 7.5-8.0 for DNA and many other modified oligos [19]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Assessing Stability and Engineering Delivery

For researchers focused on improving oligonucleotide stability and binding affinity, understanding metabolic fate is paramount. In vitro metabolic stability assays using systems like plasma, liver homogenate, and S9 fractions provide critical early data on how quickly your oligonucleotide candidate might be degraded or eliminated. These assays are a cornerstone of discovery, enabling you to identify metabolic soft spots, compare analogues, and select leads with the highest probability of success before committing to costly in vivo studies. This guide provides troubleshooting and procedural specifics to integrate these assays seamlessly into your oligonucleotide research workflow.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Plasma Stability Assay Protocol

This protocol assesses the stability of your oligonucleotide in plasma, predicting susceptibility to nucleases and plasma esterases, a key first step for compounds intended for systemic administration.

Detailed Methodology:

- Preparation: Thaw pooled plasma (from human or relevant animal species) and keep on ice. Centrifuge briefly to remove particulates.

- Incubation Setup: Pre-warm a water bath or heating block to 37°C. In a microcentrifuge tube, add plasma to achieve a final volume of 100 µL per time point. Add your oligonucleotide test compound (from a DMSO stock) to a final concentration of 1 µM, ensuring the organic solvent concentration does not exceed 0.1% [21].

- Time Points: Initiate the reaction by transferring the tube to the 37°C incubator. Remove 50 µL aliquots at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes) and immediately mix with a quenching solvent (e.g., 100 µL of ice-cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard) [21].

- Termination and Analysis: Vortex the quenched samples and centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 14,000 rpm) for 10 minutes to precipitate proteins. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to determine the percentage of parent oligonucleotide remaining at each time point [22].

S9 Fraction Metabolic Stability Assay Protocol

The liver S9 fraction offers a balanced view of both Phase I (e.g., cytochrome P450) and Phase II (e.g., UGTs, SULTs) metabolism, making it highly valuable for a comprehensive stability profile [23] [22].

Detailed Methodology:

- Reagent Preparation: Thaw liver S9 fraction (e.g., 20 mg/mL protein concentration) on ice and dilute in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to a working concentration of 1 mg/mL [22]. Prepare a cofactor solution containing NADPH (for Phase I), UDPGA (for glucuronidation), and PAPS (for sulfation) in the same buffer.

- Incubation Setup: In a 96-well plate, combine the diluted S9 fraction, cofactor solution, and your oligonucleotide test compound (1 µM final concentration). The final incubation volume is typically 100 µL [22].

- Time Points: Place the plate in a 37°C incubator. Remove aliquots at specific time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes) and quench them with two volumes of ice-cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard [22].

- Termination and Analysis: Centrifuge the quenched plates to pellet precipitated proteins and analyze the supernatant via LC-MS/MS to quantify the disappearance of the parent compound over time [22].

Diagram 1: S9 Fraction Assay Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in a standard S9 fraction metabolic stability assay.

Liver Homogenate (Full) Assay Protocol

A full liver homogenate contains all soluble and membrane-bound enzymes and organelles, providing the most complete in vitro representation of hepatic metabolism, though it is less commonly used than S9 or microsomes.

Detailed Methodology:

- Preparation: Thaw liver homogenate on ice. The homogenate is typically used at a protein concentration higher than S9, often between 1-2 mg/mL.

- Incubation Setup: The setup is identical to the S9 assay. Combine homogenate, necessary cofactors (NADPH, UDPGA, etc.), and test compound (1 µM) in a suitable buffer.

- Time Points and Quenching: Follow the same procedure as the S9 assay, taking aliquots at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes and quenching with acetonitrile.

- Analysis: After centrifugation, analyze the supernatant by LC-MS/MS to track parent compound depletion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Stability Assays.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Assay | Key Considerations for Oligonucleotides |

|---|---|---|

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes [21] | Intact cells containing full complement of Phase I/II enzymes; considered the "gold standard" for hepatic metabolism. | Assess stability against nucleases and conjugating enzymes; monitor for cellular uptake. |

| Liver S9 Fraction [23] [22] | Supernatant from liver homogenate containing both microsomal & cytosolic enzymes. | Ideal for detecting both oxidative and conjugative metabolism in a single, cost-effective system. |

| Liver Microsomes [23] | Subcellular fraction rich in endoplasmic reticulum; contains CYP450 & UGT enzymes. | Primarily informs on Phase I oxidation; may miss key cytosolic degradation pathways. |

| NADPH Regenerating System [21] [22] | Cofactor essential for cytochrome P450 (CYP)-mediated Phase I oxidation. | Critical if oxidative metabolism is a suspected clearance route for modified oligonucleotides. |

| UDPGA & PAPS [22] | Cofactors for Phase II glucuronidation and sulfation reactions, respectively. | Important for studying conjugation of novel oligonucleotide structures or attached small molecules. |

| Plasma (Human/Animal) | Matrix to assess stability against circulating nucleases and esterases. | Crucial first assay for oligonucleotides to predict stability in bloodstream. |

| Positive Control Compounds (e.g., Midazolam, Verapamil) [21] [22] | Verify metabolic activity of the biological system (e.g., S9, microsomes). | Ensure system functionality before running valuable oligonucleotide test compounds. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between hepatocyte, S9, and microsomal stability assays, and which should I use first for my oligonucleotide program?

- Hepatocytes are intact cells and represent the most physiologically relevant system, containing a full suite of metabolic enzymes and cellular compartments [23]. However, they are more expensive and labor-intensive.

- Liver S9 fractions contain both microsomal (Phase I) and cytosolic (Phase II) enzymes, offering a comprehensive profile at a lower cost and higher throughput than hepatocytes [23] [22].

- Liver microsomes are limited to enzymes found in the endoplasmic reticulum, primarily CYP450s and UGTs, and lack cytosolic enzymes [23].

Recommendation: For a new oligonucleotide series, begin with a plasma stability assay to gauge nuclease susceptibility. Follow with an S9 assay to get a balanced, cost-effective overview of both Phase I and II hepatic metabolic pathways [23].

Q2: My metabolic stability data shows a poor correlation with in vivo clearance. What could be the reason? Several factors can cause this disconnect:

- Extrahepatic Metabolism: Your compound may be significantly metabolized in tissues like the kidneys, lungs, or intestines, which are not represented in standard liver-based assays [24].

- Transporters: Active uptake or efflux by transporters in vivo can significantly influence hepatic exposure, a factor absent in cell-free systems (S9, microsomes) [23].

- Protein Binding: High plasma protein binding can reduce the free fraction of drug available for metabolism in vivo, an effect not fully captured in vitro.

- Vendor Differences: Different vendors' liver preparations (e.g., microsomes) can have varying enzyme activities and profiles, leading to different stability results. It is critical to use consistent and well-characterized lots [25].

Q3: What controls are essential for a reliable S9 or microsomal stability assay? Always include:

- Positive Control: A compound with known high metabolic turnover (e.g., verapamil, midazolam) to confirm the metabolic activity of your S9/microsomal preparation is adequate [21] [22].

- Negative Control without Cofactor: An incubation without the NADPH cofactor. If the parent compound depletes without NADPH, it suggests non-enzymatic degradation or metabolism by non-P450 enzymes, which is a critical observation [22].

- Blank Control: Contains only vehicle (e.g., 0.1% DMSO) to monitor for any interfering peaks in the analytical method [22].

Q4: The turnaround time for metabolic stability assays is bottlenecking my project. Are there high-throughput options? Yes. The field is moving towards high-throughput automation. Assays can be run in 384-well formats with robotic liquid handling systems for incubation and sample cleanup [26]. Furthermore, fast UPLC/MS methods and automated data analysis pipelines can significantly reduce the time from experiment to data delivery, allowing for the screening of thousands of compounds [26].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Depletion of Parent Compound | Inactive biological system. Incorrect cofactor. Compound not a substrate for hepatic enzymes. | - Run a positive control (e.g., Verapamil) to verify system activity [22].- Confirm cofactor (NADPH) was added and is fresh.- Investigate extrahepatic metabolism or non-metabolic clearance (e.g., biliary, renal). |

| Extremely Rapid Depletion at Time Zero | Non-enzymatic degradation. Instability in assay buffer. Precipitation. | - Include a negative control without cofactors to identify non-enzymatic loss [22].- Check compound solubility in aqueous buffer; consider alternative solvent vehicles, keeping DMSO ≤0.1% [21]. |

| High Variability Between Replicates | Poor pipetting accuracy. Inconsistent cell or protein concentration. Clogged LC-MS/MS inlet. | - Use calibrated pipettes and practice good liquid handling technique.- Ensure S9/hepatocyte suspensions are homogenous before aliquoting.- Centrifuge or filter samples prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. |

| Poor LC-MS/MS Chromatography | Matrix effect from plasma/S9. Ion suppression. Co-eluting metabolites. | - Improve sample cleanup/extraction protocols (e.g., protein precipitation, solid-phase extraction).- Optimize LC gradient and column for your specific compound class. |

| Discrepancy Between S9 and Hepatocyte Data | Permeability barrier in hepatocytes limiting intracellular access. Differences in cofactor levels. | - If stable in S9 but not in hepatocytes, consider low cellular permeability.- If unstable in S9 but stable in hepatocytes, it could be due to saturated transport or differing cofactor concentrations [23]. |

Diagram 2: No Depletion Troubleshooting Path. A logical flowchart to diagnose an experiment where the test compound shows no metabolic depletion.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Synthesis & Deprotection

Q: My oligonucleotide synthesis yields are low, and coupling efficiency seems poor. What could be the cause? A: This is frequently caused by water contamination in moisture-sensitive reagents like phosphoramidites. Water hydrolyzes phosphoramidites, rendering them inactive for coupling.

- Solution: Ensure absolute anhydrous conditions for all synthesis reagents. Treat phosphoramidites and other moisture-sensitive reagents with activated 3Å molecular sieves for at least 48 hours before use to scavenge trace water [27].

Q: I observe multiple bands or incomplete deprotection in my synthetic RNA, especially in pyrimidine-rich sequences. How can I fix this? A: This is a classic symptom of incomplete removal of 2'-O-silyl protecting groups due to wet deprotection reagents. The reaction is highly sensitive to water content in the defluorination agent, tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) [27].

- Solution: Ensure your TBAF is dry. Upon receipt, treat TBAF with 3Å molecular sieves to reduce water content to below 5%. Use fresh, small bottles of TBAF to minimize exposure to atmospheric moisture over time [27].

Analysis & Characterization

Q: My MALDI-TOF MS spectra for oligonucleotides have poor signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios and inconsistent results. How can I improve reproducibility? A: Reproducibility in MALDI-TOF MS is highly dependent on matrix selection, solvent composition, and spotting technique [28].

- Solution:

- Matrix Selection: For a broad mass range (4-10 kDa), use the ionic matrix 6-aza-2-thiothymine (ATT) with 1-methylimidazole (1-MI). This combination provides high mass precision and reduced standard deviation [28].

- Additives: Incorporate the additive 1-methylimidazole to improve spot homogeneity and signal quality [28].

- Spotting Method: The two-layer method (matrix first, then sample) can yield more homogeneous crystals and better reproducibility than the dried droplet method [28].

Q: Which LC technique should I choose for analyzing therapeutic oligonucleotides and their impurities? A: The choice depends on your analyte length and goal [29] [9].

- Anion-Exchange Chromatography (AEC): Ideal for separating oligonucleotides by length, providing single-nucleotide resolution for sequences up to 50-100 nucleotides. Best for process-scale purification and analyzing n-1 impurities [29].

- Ion-Pair Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (IP-RPLC): Often coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) for its excellent selectivity and sensitivity in detecting metabolites and impurities, especially for shorter sequences [29] [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized MALDI-TOF MS Sample Preparation for Oligonucleotides

This protocol is designed to enhance signal intensity, mass precision, and reproducibility for oligonucleotide analysis [28].

1. Materials and Reagents:

- Matrix: 6-Aza-2-thiothymine (ATT), ≥98%

- Organic Base: 1-Methylimidazole (1-MI), 99%

- Solvents: Acetonitrile (ACN, LC/MS grade), Water (HPLC grade)

- Additive: Diammonium hydrogen citrate (DAC)

- Oligonucleotide sample, desalted

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Prepare Ionic Liquid Matrix.

- Dissolve ATT in methanol (20 mg/mL).

- Add an equimolar amount of 1-Methylimidazole.

- Vortex the mixture for 5 minutes.

- Evaporate the solvent to dryness under a stream of nitrogen or in a vacuum concentrator.

- Redissolve the resulting organic salt in a 1:1 (vol/vol) ACN/H₂O solution containing 10 mg/mL DAC to a final concentration of 75 mg/mL [28].

- Step 2: Prepare Sample Solution. Dilute the oligonucleotide to a concentration of 10-50 µM in nuclease-free water.

- Step 3: Apply Sample to MALDI Target (Two-Layer Method).

- Spot 0.5 µL of the prepared ionic matrix solution onto the target plate and allow it to dry completely at room temperature.

- Once the matrix layer is dry, overlay it with 0.5 µL of the diluted oligonucleotide sample [28].

- Step 4: Mass Spectrometry Analysis. Acquire data in linear negative ion mode for oligonucleotides.

The workflow for this optimized protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: In Vitro Metabolic Stability Assay in Biological Matrices

This protocol helps predict the in vivo stability of oligonucleotides by assessing their resistance to nucleases in serum or liver homogenate [30] [31].

1. Materials and Reagents:

- Oligonucleotide test compound

- Biological matrix (e.g., mouse or human plasma/serum, mouse liver homogenate)

- Incubation buffer (e.g., Tris-based, with MgCl₂ for certain nucleases)

- Stopping solution (e.g., proteinase K, organic solvents, or specific chelating agents like EDTA)

- LC-MS or gel electrophoresis equipment for analysis

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Preparation. Pre-incubate the biological matrix (e.g., 95 µL of mouse serum) at 37°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Step 2: Initiation. Add 5 µL of the oligonucleotide working solution to the pre-warmed matrix to start the reaction. Mix gently and immediately.

- Step 3: Incubation. Maintain the reaction mixture at 37°C. Withdraw aliquots (e.g., 20 µL) at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes). For highly stable oligonucleotides, extend time points to several hours [30].

- Step 4: Termination. Immediately mix each withdrawn aliquot with a stopping solution. For serum incubations, a common method is to add 80 µL of a solution containing 2.5 mg/mL proteinase K and incubate at 50°C for 30 minutes to digest proteins, followed by solid-phase extraction (SPE) to isolate the oligonucleotide [31].

- Step 5: Analysis. Analyze the samples using a validated LC-UV/MS method or gel electrophoresis to quantify the remaining intact oligonucleotide and identify degradation products [31].

3. Data Analysis:

- Plot the percentage of intact oligonucleotide remaining versus time.

- Calculate the half-life (t₁/₂) of the oligonucleotide using a non-compartmental analysis or by fitting to an appropriate decay model.

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in selecting and executing a stability assay:

Structured Data for Experimental Optimization

| Matrix | Additive / Solvent System | Key Performance Characteristics | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATT (Ionic) | 1-MI / ACN:H₂O (1:1) with DAC | High mass precision; Reduced standard deviation; Homogeneous spots | General purpose, especially for high precision mass measurement |

| 3-HPA | DAC / ACN:H₂O (1:1) | Performance highly variable with solvent/additive; Moderate S/N | Use with caution; requires in-lab optimization |

| 2,4,6-THAP | DAC / ACN:H₂O (1:1) | Suppresses alkali adducts; Good resolution for smaller oligos | Analysis where salt adduction is a primary concern |

| Method / Matrix | Incubation Conditions | Key Measured Outcomes | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum Stability | 37°C; Aliquots taken from minutes to hours | Half-life (t₁/₂); Metabolite ID via LC-MS | Advantage: High physiological relevance. Limitation: Species-specific nuclease variation. |

| Liver Homogenate Stability | 37°C; Extended time points (hours) | Tissue-specific degradation profile; Major metabolites | Advantage: Models hepatic clearance. Limitation: Complex matrix. |

| Specific Nuclease (e.g., PDEI) | Buffer with Mg²⁺; Short incubation (mins) | Rate of exonuclease cleavage; Effect of backbone modifications | Advantage: Mechanistic insight. Limitation: Low physiological complexity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside Phosphoramidites | Building blocks for solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis. | Require strict anhydrous handling; use with 3Å molecular sieves to maintain efficacy [3] [27]. |

| 3Å Molecular Sieves | Desiccant for scavenging water from moisture-sensitive reagents. | Essential for maintaining anhydrous conditions for phosphoramidites and TBAF; activate before use [27]. |

| Tetrabutylammonium Fluoride (TBAF) | Reagent for deprotecting 2'-O-silyl groups in RNA synthesis. | Water content is critical; must be kept <5% for complete deprotection of pyrimidines [27]. |

| Ionic MALDI Matrices (e.g., ATT + 1-MI) | Matrix for MALDI-TOF MS analysis of oligonucleotides. | Improves spot homogeneity, signal reproducibility, and mass precision compared to conventional matrices [28]. |

| Diammonium Hydrogen Citrate (DAC) | Additive for MALDI matrix solutions. | Suppresses the formation of alkali metal adducts ([M+Na]⁺, [M+K]⁺), leading to cleaner spectra [28]. |

| Triethylamine / Hexafluoroisopropanol | Ion-pairing reagents for LC-MS analysis of oligonucleotides. | Critical for achieving good chromatographic separation and peak shape in reversed-phase LC-MS methods [9] [30]. |

Validating In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) for Predictive Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the different levels of IVIVC, and which is most valuable for regulatory purposes? IVIVCs are categorized into several levels based on their predictive power. Level A is the most comprehensive and valuable for regulatory submissions, as it represents a point-to-point correlation between the in vitro dissolution profile and the in vivo input rate of the drug [32]. Level B compares mean in vitro dissolution time to mean in vivo residence time, while Level C correlates a single dissolution time point with a pharmacokinetic parameter like AUC or Cmax. Multiple Level C correlates several dissolution time points with pharmacokinetic parameters. Level D is a qualitative analysis with no regulatory value [32] [33].

Q2: Our oligonucleotide conjugate (AOC) is a complex molecule. What are the main challenges in developing a predictive IVIVC for such therapeutics? For novel therapeutics like Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs), development is challenging due to their structural complexity and mechanistic diversity [34]. These factors contribute directly to manufacturing and quality control challenges. Ensuring therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity requires rigorous strategies for the design, manufacturing, and quality control of AOCs [34]. Furthermore, analytical separation and purification of oligonucleotides are complex bioanalytical challenges due to their intricate impurity profiles, necessitating custom analytical protocols for each molecule [9].

Q3: When is it inappropriate to use mean data for IVIVC development? Using mean in vivo data can be inappropriate when there is significant variability in key pharmacokinetic parameters between subjects. Specifically, if the lag time (Tlag) and time to maximum concentration (Tmax) vary significantly across individuals, the mean curve will not accurately reflect individual behaviors [35]. This is often the case for formulations whose performance is heavily influenced by physiology, such as enteric-coated products. For drugs with high intra-subject variability, IVIVCs are generally discouraged as the study power and predictability are low [35].

Q4: Can a validated IVIVC replace a bioequivalence study for a formulation change? Yes, a validated IVIVC can serve as a surrogate for in vivo bioequivalence studies in certain circumstances, such as for scale-up and post-approval changes (SUPAC) [36]. When an IVIVC has been established and validated for internal and external predictability, it can be used to set dissolution specifications and justify that formulation changes will not impact the in vivo performance, thereby obtaining a biowaiver [37] [35] [33].

Troubleshooting Common IVIVC Challenges

Issue 1: Poor Correlation BetweenIn VitroDissolution andIn VivoAbsorption

| Potential Cause | Investigation Approach | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Non-biorelevant dissolution method | Compare dissolution in compendial media (e.g., USP buffers) versus biorelevant media (e.g., FaSSIF/FeSSIF) [36]. | Develop a biopredictive dissolution method that mimics the gastrointestinal environment, including pH gradients and surfactant content. |

| Formulation behavior is physiology-dependent | Review physiology (e.g., gastric emptying, GI transit times) and its impact on drug release. | For complex formulations like lipids, use advanced in vitro models (e.g., lipolysis assays) that simulate digestion [32]. |

| Drug permeability is rate-limiting | Determine the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) class of the drug. | IVIVC is most feasible when dissolution is the rate-limiting step (e.g., BCS Class II drugs). It is difficult to establish for permeability-limited drugs [33]. |

Issue 2: Failure in Predictability During IVIVC Validation

| Potential Cause | Investigation Approach | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in in vivo data | Assess the inter- and intra-subject variability of key PK parameters (Cmax, AUC). | If intra-subject variability is high, IVIVC may not be feasible. For low variability, ensure individual subject profiles are analyzed [35]. |

| Incorrect deconvolution method | Compare different methods for estimating the in vivo absorption profile (e.g., numerical deconvolution vs. Wagner-Nelson) [37]. | Use a deconvolution method that is appropriate for the drug's pharmacokinetics (e.g., compartmental model). |

| Invalid mathematical model | Check the regression parameters of the correlation model (e.g., linear, nonlinear). | Ensure the model structure is sound. Explore time-scaling or other transformations to improve the relationship between in vitro and in vivo profiles [35]. |

Issue 3: Inability to Establish IVIVC for Lipid-Based Formulations (LBFs)

| Potential Cause | Investigation Approach | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Standard dissolution tests ignore lipid digestion | Use an in vitro lipolysis model to simulate the dynamic process of lipid digestion [32]. | Integrate lipolysis assays and permeation studies into the in vitro test to better capture the in vivo dynamics of LBFs. |