Spectrophotometry for DNA and RNA Analysis: A Complete Guide to Concentration, Purity, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using UV-Vis spectrophotometry for the quantification and purity assessment of DNA and RNA.

Spectrophotometry for DNA and RNA Analysis: A Complete Guide to Concentration, Purity, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using UV-Vis spectrophotometry for the quantification and purity assessment of DNA and RNA. It covers foundational principles, from the Beer-Lambert law to the significance of A260/A280 ratios, and delivers detailed, step-by-step protocols for reliable measurement. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, explores method validation parameters, and offers a comparative analysis with fluorometry to guide instrument selection. By synthesizing methodological guidance with quality control and advanced application insights, this resource aims to empower scientists to generate accurate, reproducible nucleic acid data crucial for downstream molecular biology techniques.

The Principles of Spectrophotometry: Mastering Nucleic Acid Absorbance Fundamentals

In molecular biology and pharmaceutical development, the accurate quantification of nucleic acids is a foundational step that directly influences the success of downstream applications, from basic PCR to cutting-edge mRNA vaccine production. At the heart of many quantification workflows lies the Beer-Lambert Law, a principle of spectroscopy that enables researchers to determine the concentration of molecules in solution. This law describes the linear relationship between the absorbance of light and the concentration of an absorbing substance. For DNA and RNA analysis, this translates to using absorbance at 260 nm to calculate nucleic acid concentration, a method valued for its simplicity and rapidity. However, the reliance on this principle also introduces specific limitations concerning sensitivity, specificity, and susceptibility to contaminants. This guide provides an objective comparison of quantification techniques rooted in the Beer-Lambert Law against modern fluorescence-based alternatives, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform the choices of researchers and drug development professionals.

The Fundamental Principle: The Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) is a fundamental principle in spectrophotometry that provides the mathematical basis for quantifying the concentration of a substance in a solution [1]. It states that the absorbance (A) of light by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species and the path length (l) the light takes through the solution [2] [1].

The law is expressed by the equation: A = ε * c * l

Where:

- A is the measured absorbance (no units).

- ε is the molar absorptivity or extinction coefficient (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹), a constant that indicates how strongly a specific chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [1].

- c is the concentration of the solution (mol/L).

- l is the path length of the cuvette or measurement vessel (cm) [1].

In practical terms for nucleic acid quantification, this equation is rearranged to solve for concentration. The extinction coefficient (ε) is well-established for nucleic acids, allowing instruments to calculate concentration directly from the absorbance reading at 260 nm [3]. An absorbance of 1.0 at 260 nm corresponds to approximately 50 µg/mL for double-stranded DNA, 33 µg/mL for single-stranded DNA, and 40 µg/mL for RNA [3] [4].

Application in RNA and DNA Quantification

UV spectrophotometry, powered by the Beer-Lambert Law, is a cornerstone technique for the initial assessment of nucleic acid samples.

- Concentration Measurement: The concentration of a DNA or RNA sample is directly determined by measuring its absorbance at 260 nm (A260) and applying the Beer-Lambert law [2] [4]. This simple calculation allows researchers to swiftly determine if a sample meets the concentration requirements for their next experiment.

- Purity Assessment: Spectrophotometers also measure absorbance at other wavelengths to assess sample purity through key ratios [2] [5] [6]:

- A260/A280 Ratio: This ratio assesses protein contamination. Pure DNA typically has a ratio of ~1.8, while pure RNA has a ratio of ~2.0 [2] [5]. Significantly lower ratios suggest residual protein, as proteins absorb light strongly at 280 nm due to aromatic amino acids [6].

- A260/A230 Ratio: This ratio assesses contamination from salts, solvents, or organic compounds like guanidine thiocyanate or phenol, which absorb at 230 nm [2] [5]. A ratio of >1.8 is generally considered acceptable for pure nucleic acids [2].

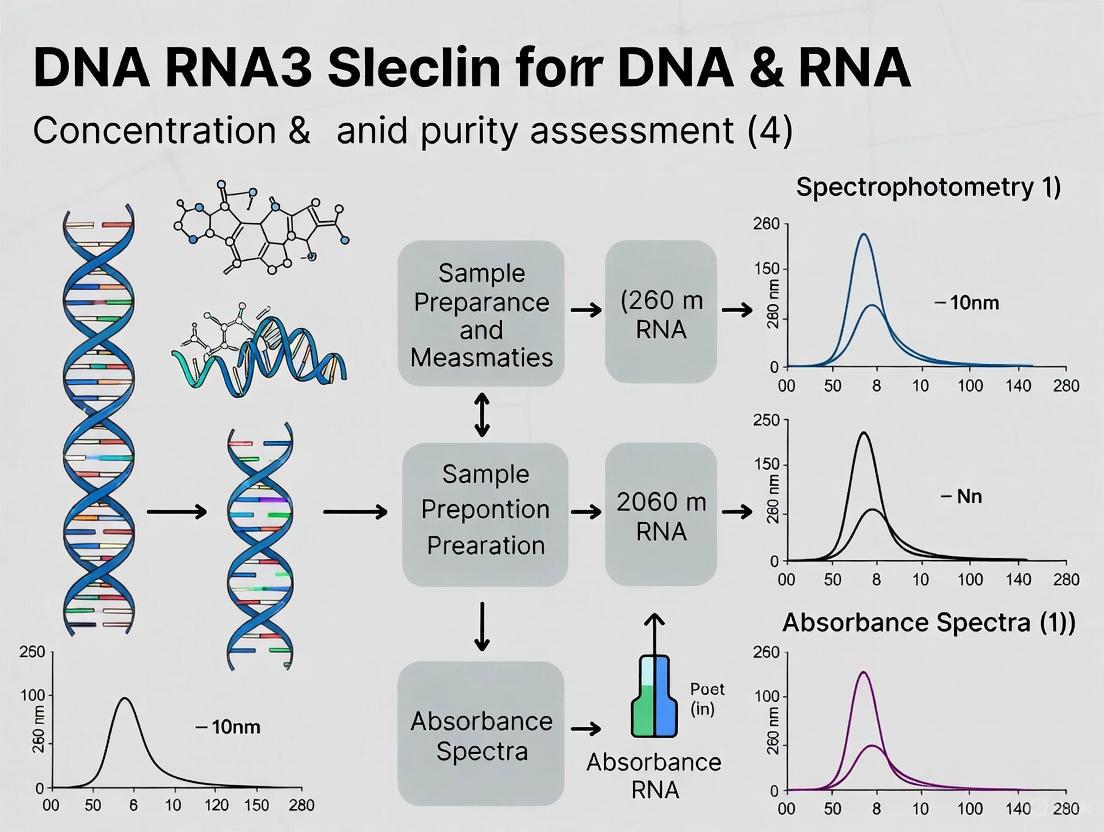

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and decision points for using this principle in nucleic acid analysis.

Comparative Analysis: Spectrophotometry vs. Fluorometry

While UV spectrophotometry is a versatile workhorse, fluorometry has emerged as a powerful alternative, especially for sensitive or demanding applications. The table below provides a direct, data-driven comparison of these two core techniques.

| Evaluation Criteria | UV Spectrophotometry | Fluorometry |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Beer-Lambert Law (light absorption) [2] [7] | Fluorescence emission from dye-bound nucleic acids [2] [5] |

| Specificity | Low; cannot distinguish between DNA, RNA, or free nucleotides [2] [7] | High; dyes can be specific for dsDNA, ssDNA, or RNA [2] [7] |

| Sensitivity Range | 2-2000 ng/µL (dsDNA) [7] | 0.01-100 ng/µL (dsDNA) [7] |

| Purity Assessment | Direct via A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios [2] [6] | Indirect; requires sample dilution which can dilute contaminants [7] |

| Key Advantage | Simple, rapid, and cost-effective; provides direct purity assessment [2] [7] | Superior sensitivity and specificity; ideal for low-concentration samples [2] [5] [7] |

| Main Limitation | Susceptible to interference from common contaminants [2] [6] | Requires specific, often expensive, fluorescent dyes [2] [7] |

| Ideal Use Case | Initial quality control of pure, concentrated samples [2] [7] | Quantifying low-abundance samples, NGS library prep, RNA/DNA mixtures [2] [7] |

Experimental Insight: The limitations of spectrophotometry are pronounced in modern therapeutics. A 2024 study highlighted that modified nucleosides (e.g., pseudouridine (Ψ) in mRNA vaccines) alter the spectrophotometric properties of RNA, leading to significant underestimation of concentration when using the standard Beer-Lambert calculation [8]. This necessitates advanced tools like the mRNACalc web server for accurate dosing, which is critical for clinical efficacy and safety [8].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The consistent execution of nucleic acid quantification relies on a suite of specific reagents and instruments. The following table catalogs key materials and their functions in standard experimental workflows.

| Reagent/Instrument | Function in Quantification |

|---|---|

| Microvolume Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) | Measures absorbance of tiny sample volumes (1-2 µL) without a cuvette, calculating concentration and purity ratios [6]. |

| Fluorometer | Excites fluorescent dyes bound to nucleic acids and measures the emitted light for highly sensitive and specific quantification [5] [7]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., PicoGreen, RiboGreen) | Bind selectively to specific nucleic acid types (dsDNA or RNA), enabling sensitive detection in fluorometry [5]. |

| TE Buffer (pH 8.0) | A slightly alkaline elution/buffer that provides stable pH for accurate and reproducible A260/A280 ratios [4]. |

| DNase or RNase Enzymes | Treat samples to remove contaminating DNA (from RNA preps) or RNA (from DNA preps) for accurate, specific quantification [4]. |

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Performs capillary electrophoresis to provide detailed information on RNA integrity and concentration, beyond simple absorbance [4]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Spectrophotometric RNA Quantification

This protocol outlines a standardized method for quantifying RNA using a microvolume spectrophotometer, incorporating best practices to mitigate common issues.

Materials and Reagents

- Purified RNA sample

- Nuclease-free water or TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0)

- RNase-free microtubes

- Microvolume UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Thermo Scientific NanoDrop)

- Lint-free wipes for cleaning the instrument pedestal

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the spectrophotometer and its associated software. Initialize the nucleic acid quantification application.

- Blank Measurement: Using a lint-free wipe, thoroughly clean the upper and lower measurement pedestals. Pipette 1-2 µL of the chosen blank solution (nuclease-free water or TE buffer) onto the lower pedestal. Close the arm and execute the "Blank" measurement. Clean the pedestals after the measurement [6] [4].

- Sample Measurement: Clean the pedestals again. Pipette 1-2 µL of the RNA sample onto the lower pedestal. Close the arm and initiate the sample measurement. The instrument will display the absorbance spectrum and calculate the concentration and purity ratios automatically.

- Data Recording and Interpretation: Record the sample concentration (in ng/µL), the A260/A280 ratio, and the A260/A230 ratio. Clean the pedestals thoroughly before the next sample. For reliability, it is recommended to perform at least two technical replicates per sample [6].

- Troubleshooting and Optimization:

- Low A260/A280 Ratio (<1.8): Indicates protein contamination. Consider additional purification steps, such as phenol-chloroform extraction [2] [4].

- Low A260/A230 Ratio (<1.8): Suggests contamination with salts or organic compounds (e.g., guanidine thiocyanate, ethanol). Perform an additional precipitation and wash step with 70% ethanol [2] [6].

- Abnormal Spectral Peak: A peak shifted toward 270 nm may indicate phenol contamination [6].

- pH Sensitivity: For consistent A260/A280 ratios, always use a slightly alkaline buffer like TE (pH 8.0) instead of water, which can have an acidic pH and artificially depress the ratio [4].

The Beer-Lambert Law remains an indispensable principle for the initial quantification and purity assessment of nucleic acids, offering unparalleled speed and simplicity. However, a comparative analysis clearly shows that its utility is best leveraged in conjunction with other techniques. For high-concentration, pure samples, spectrophotometry provides a complete and rapid assessment. In contrast, for sensitive applications, complex sample matrices, or the precise quantification of modified RNAs used in modern therapeutics, fluorometry's superior specificity and sensitivity make it the indispensable tool. A robust quantification strategy often employs both methods: spectrophotometry for an initial quality check and fluorometry for final, precise measurement before critical downstream applications. This dual approach ensures the accuracy and reproducibility required for successful research and drug development.

The accurate quantification of nucleic acids is a cornerstone of molecular biology, with spectrophotometric absorbance at 260 nm serving as the fundamental principle for concentration determination. This guide details the photophysical properties of DNA and RNA that dictate this specific absorbance maximum, objectively compares spectrophotometric and fluorometric quantification technologies, and provides validated experimental protocols for researchers. Supporting data on instrument performance, purity assessments, and troubleshooting guidelines are synthesized to inform method selection for downstream applications in drug development and biomedical research.

The interaction of nucleic acids with ultraviolet (UV) light provides the basis for one of the most routinely performed measurements in molecular biology laboratories. The nitrogenous bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine, thymine, and uracil—that comprise DNA and RNA exhibit strong absorption of UV light due to their complex, conjugated ring structures [9]. These aromatic heterocycles undergo π→π* electronic transitions when exposed to UV radiation, with maximal absorption occurring at a characteristic wavelength of 260 nanometers (nm) [6] [9]. This specific photophysical property enables researchers to non-destructively determine nucleic acid concentration in solution using the Beer-Lambert law, which relates the absorbance of light to the concentration of the absorbing molecule [10] [9].

The consistent absorption maximum at 260 nm across different nucleic acid types and sources makes it a critical parameter for quantification. According to the Beer-Lambert law, A = εlc, where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient, l is the path length, and c is concentration [9]. For double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), an absorbance of 1.0 at 260 nm corresponds to approximately 50 μg/mL, while for RNA, the equivalent absorbance corresponds to 40 μg/mL [11] [12]. These conversion factors are standardized across the field, allowing for consistent concentration calculations regardless of the specific spectrophotometer instrument used.

Fundamental Principles of 260 nm Absorbance

Molecular Basis of UV Absorption

The exceptional absorbance of nucleic acids at 260 nm stems from the resonant structures of their purine (adenine, guanine) and pyrimidine (cytosine, thymine, uracil) bases. The delocalized π-electron systems within these heterocyclic rings can be excited to higher energy states by photons of specific energy, corresponding to the UV range of the electromagnetic spectrum. Each base has a slightly different absorption profile, but collectively they create the characteristic peak at 260 nm that is exploited for quantification purposes [9]. This property is so fundamental that it enables detection of nucleic acids at concentrations as low as 2-5 ng/μL in microvolume spectrophotometers [10].

Beer-Lambert Law and Concentration Calculations

The relationship between absorbance and nucleic acid concentration follows the Beer-Lambert law, expressed as A = εlc, where A is the measured absorbance, ε is the wavelength-dependent molar absorptivity coefficient, l is the path length through which light travels, and c is the molar concentration of the analyte [10] [9]. For practical laboratory applications, this is simplified to concentration calculations using established conversion factors:

- dsDNA concentration (μg/mL) = A260 × dilution factor × 50 μg/mL [12] [13]

- RNA concentration (μg/mL) = A260 × dilution factor × 40 μg/mL [12]

For accurate quantification, absorbance readings at 260 nm should fall between 0.1 and 1.0, which represents the linear range for most instruments [11] [13]. Samples falling outside this range should be diluted or concentrated accordingly to ensure measurement accuracy.

Comparative Analysis of Quantification Methods

Spectrophotometry vs. Fluorometry: Technical Comparison

While both methods quantify nucleic acids, they differ significantly in their underlying principles, sensitivity, and applications. The table below summarizes the key differences:

Table 1: Comparison of UV Spectrophotometry and Fluorometry for Nucleic Acid Quantification

| Parameter | UV Spectrophotometry | Fluorometry |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measures intrinsic absorbance of bases at 260 nm [10] | Measures fluorescence from dyes that selectively bind nucleic acids [10] |

| Sensitivity | 1-2 ng/μL (NanoDrop) [10] | 0.005-0.05 ng/μL (Qubit) [10] |

| Specificity | Low; cannot distinguish between DNA and RNA [10] [12] | High; dyes can be specific for dsDNA, ssDNA, or RNA [10] [13] |

| Purity Information | Provides A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios [10] | No purity information [10] |

| Sample Prep | Simple; no additional reagents [10] | Requires fluorescent dyes and standards [10] |

| Cost & Throughput | Lower cost per sample; high throughput [10] | Higher cost per sample; medium throughput [10] |

Instrument Performance Comparison

Different instruments offer varying performance characteristics for nucleic acid quantification. The following table compares detection limits and sample requirements across common platforms:

Table 2: Instrument Detection Limits and Sample Requirements

| Instrument | Method | Lower Detection Limit (dsDNA) | Sample Volume | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NanoDrop Ultra | UV Spectrophotometry | 1.0 ng/μL (pedestal) [10] | 1 μL [10] | Single sample [10] |

| NanoDrop Eight | UV Spectrophotometry | 2.0 ng/μL [10] | 1 μL [10] | 8 samples [10] |

| NanoDrop Ultra FL | Fluorometry | 0.05 ng/μL [10] | 1-10 μL [10] | Single sample [10] |

| Qubit 4 | Fluorometry | 0.005 ng/μL [10] | 1-20 μL [10] | Single sample [10] |

| Multiplate Readers | Both | Varies by format and assay [10] | As little as 2 μL [10] | 16-384 samples [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Absorbance Measurement

Standard Spectrophotometric Quantification Protocol

Materials Required:

- Purified DNA or RNA sample

- Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop, DeNovix) or UV-transparent cuvettes

- Appropriate blank solution (same as sample buffer, typically TE buffer or nuclease-free water)

- Micropipettes and tips

Procedure:

- Blank Measurement: Dispense 1-2 μL of the blank solution (the buffer used to elute or dilute the sample) onto the measurement pedestal or into a cuvette. Initiate the blank measurement [12] [6].

- Sample Measurement: Wipe the pedestal clean and apply 1-2 μL of the nucleic acid sample. For cuvette-based systems, dilute the sample appropriately to ensure A260 readings fall between 0.1-1.0 [13].

- Data Recording: Record the A260 value for concentration calculation and the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios for purity assessment [13] [14].

- Concentration Calculation: Calculate nucleic acid concentration using the appropriate conversion factor (50 μg/mL for dsDNA, 40 μg/mL for RNA per 1 A260 unit) multiplied by any dilution factor [12] [13].

Validation Parameters:

- Linearity: Correlation coefficients should be R ≥ 0.9950 across the working range [15].

- Precision: Coefficient of variation (% CV) should be ≤2% for repeatability and reproducibility [15].

- Trueness: Bias values should be lower than Z-test with 95% confidence level, with recovery percentages within 100% ± 5% [15].

Method Validation and Quality Control

For rigorous scientific research and regulated environments, method validation should include:

- Linearity Assessment: Performed through calibration curves generated by serial dilution of Standard Reference Material DNA (e.g., NIST SRM 2372) [15].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ) Determination: Calculated from multiple measurements of blank samples [15].

- Precision Evaluation: Under both repeatability and reproducibility conditions using multiple DNA concentrations [15].

- Stability Testing: DNA samples typically show stability for 60 days at 2-4°C [15].

Purity Assessment and Contaminant Detection

Interpretation of Absorbance Ratios

The table below outlines expected purity ratios and deviations indicating contamination:

Table 3: Nucleic Acid Purity Ratios and Interpretation

| Ratio | Ideal Value | Low Value Indicates | High Value Indicates |

|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 | ~1.8 (DNA) [16] [14] ~2.0 (RNA) [14] | Protein or phenol contamination [16] [14] | RNA contamination in DNA samples [16] |

| A260/A230 | 2.0-2.2 [16] [14] | Organic compounds (phenol, guanidine), chaotropic salts, or carbohydrates [16] [12] [14] | - |

Contaminant Identification via Spectral Analysis

Different contaminants exhibit characteristic absorbance profiles that can be identified through full-spectrum analysis (220-350 nm):

- Protein Contamination: Shows increased absorbance at 280 nm due to aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine), depressing the A260/A280 ratio [6].

- Phenol Contamination: Absorbs strongly at ~270 nm, potentially shifting the absorption peak from 260 nm toward 270 nm [6].

- Guanidine Salts: Exhibit strong absorbance around 230 nm, significantly depressing the A260/A230 ratio even at low concentrations (as low as 10 μM) [6].

- Carbohydrate Contamination: Appears as elevated absorbance at 230 nm, lowering the A260/A230 ratio [16].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Nucleic Acid Quantification

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| NanoDrop Spectrophotometer | Microvolume nucleic acid quantification requiring only 1-2 μL sample [10] [6] |

| Qubit Fluorometer | Highly specific DNA or RNA quantification using fluorescent dyes [10] |

| UV-Transparent Cuvettes | Absorbance measurement in traditional spectrophotometers [12] |

| Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay | Fluorometric quantification specifically for double-stranded DNA [16] [13] |

| TE Buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.5) | Optimal DNA dilution and storage buffer for stable absorbance readings [11] [6] |

| Nuclease-Free Water | RNA dilution and blank measurements [12] |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Issues and Solutions

- Low A260/A280 Ratio (<1.8): Indicates protein contamination. Solution: Repeat purification using phenol:chloroform extraction or commercial cleanup kits [16] [9].

- Low A260/A230 Ratio (<2.0): Suggests carryover of purification reagents (guanidine, phenol, salts). Solution: Ethanol precipitation with additional wash steps or use of commercial cleanup kits [16] [6].

- Inconsistent Readings: Can result from improper blanking, air bubbles, or insufficient sample cleaning. Solution: Ensure consistent blank measurement using the same buffer as samples, take multiple readings, and clean pedestals between measurements [6].

- pH Sensitivity: Absorbance ratios are pH-dependent. Acidic solutions may under-represent the A260/A280 ratio by 0.2-0.3, while basic solutions may over-represent it. Solution: Use buffered solutions (e.g., TE buffer) rather than water for consistent measurements [16] [14].

Method Selection Guidelines

- For High-Purity, Concentrated Samples: UV spectrophotometry provides rapid, comprehensive data including purity assessment [10] [13].

- For Low-Abundance Samples or Specific Quantification: Fluorometry offers superior sensitivity and specificity [10] [13].

- For Integrity Assessment: Agarose gel electrophoresis complements absorbance data by visualizing DNA size and degradation [16] [13].

- For Sequence-Specific Quantification: qPCR provides the highest specificity and sensitivity for particular targets [12] [17].

The characteristic absorbance of nucleic acids at 260 nm remains a fundamental property exploited across molecular biology for reliable quantification. While UV spectrophotometry provides a rapid, straightforward method for concentration determination and purity assessment, researchers must understand its limitations regarding sensitivity and specificity. Fluorometric methods complement spectrophotometry when working with dilute samples or when distinguishing between DNA and RNA is essential. By selecting the appropriate quantification method based on sample characteristics and downstream applications, and by rigorously validating measurement protocols, researchers can ensure the accuracy and reproducibility essential for successful experimental outcomes in drug development and biomedical research.

Accurate assessment of nucleic acid concentration and purity is a foundational step in molecular biology. The spectrophotometric purity ratios A260/A280 and A260/230 serve as critical, initial indicators of sample quality, alerting researchers to the presence of contaminants that can compromise expensive and time-consuming downstream applications [5] [16] [2]. This guide delves into the interpretation of these ratios, provides standardized experimental protocols, and compares spectrophotometry with other quantification technologies.

The Fundamentals of Nucleic Acid Purity Assessment

Core Principles of Spectrophotometry

Spectrophotometric quantification of nucleic acids is based on the Beer-Lambert law, which states that the absorbance of light by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing substance [5] [2]. The aromatic rings in the nitrogenous bases of DNA and RNA absorb ultraviolet (UV) light most strongly at a wavelength of 260 nm [5] [2]. This intrinsic property allows scientists to calculate nucleic acid concentration by measuring the absorbance at this wavelength.

The assessment of purity relies on calculating ratios of absorbance at different wavelengths. This controls for overall concentration and identifies common contaminants that absorb light at characteristic wavelengths other than 260 nm. The two most critical ratios for routine analysis are the A260/A280 ratio, which primarily indicates protein or phenol contamination, and the A260/A230 ratio, which signals the presence of salts or organic compounds [5] [14].

The Critical Distinction Between DNA and RNA

While both DNA and RNA are nucleic acids, their differing chemical structures lead to different ideal purity ratios [5]. RNA contains a ribose sugar with a hydroxyl group at the 2' carbon position, making it more chemically reactive and less stable than DNA. Furthermore, RNA uses uracil instead of thymine. These differences affect how the molecules interact with UV light, resulting in different benchmark values for a "pure" sample [5] [2]. It is therefore essential to know whether you are quantifying DNA or RNA before interpreting the results.

Interpreting A260/A280 and A260/230 Ratios

The following table provides a clear reference for interpreting the purity ratios of DNA and RNA samples.

Table 1: Interpretation of Nucleic Acid Purity Ratios

| Ratio | Ideal Value (DNA) | Ideal Value (RNA) | Low Ratio Indicates | High Ratio Indicates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 | ~1.8 [5] [16] | ~2.0 [5] [14] [2] | Protein or phenolic contamination [5] [14] | Possible RNA contamination in DNA samples [5] |

| A260/A230 | 2.0 - 2.2 [14] [16] | 2.0 - 2.2 [14] | Contamination by salts, carbohydrates, guanidine, EDTA, or phenol [5] [14] [16] | May result from a dirty blank measurement [5] |

Troubleshooting Abnormal Ratios

Deviations from the ideal ratios are common and knowing their potential causes is key to rectifying sample quality issues.

- Abnormal A260/A280: A ratio significantly lower than 1.8 for DNA or 2.0 for RNA is a strong indicator of protein contamination, a frequent carryover from the extraction process [5] [14]. Acidic or basic solutions can also skew this ratio; acidic solutions may under-represent the ratio by 0.2–0.3, while basic solutions can over-represent it [14] [16].

- Abnormal A260/A230: A low A260/230 ratio is a valuable red flag for the presence of common laboratory contaminants such as guanidine salts (used in many extraction kits), EDTA, carbohydrates, or Triton-based buffers [14] [16] [2]. The impact of these contaminants is more pronounced in dilute samples, as the contaminant's absorbance makes up a larger portion of the total signal [2].

Standardized Experimental Protocol for Accurate Measurement

Consistency in methodology is paramount for obtaining reliable and reproducible purity ratios.

Workflow for Spectrophotometric Analysis

The diagram below outlines the key steps for proper sample measurement and data interpretation.

Detailed Methodology

- Instrument Blanking: Always use the same elution buffer in which your nucleic acids are suspended (e.g., Tris-HCl, TE buffer) as the blank [5] [16]. Using water can lead to inaccurate ratios due to differences in pH and ionic strength [16].

- Sample Measurement: Pipette 1-2 µL of the sample onto the measurement pedestal for microvolume instruments, or load the solution into a quartz cuvette. Ensure the sample covers the light path completely.

- Data Collection: The instrument will measure the absorbance at 230 nm, 260 nm, and 280 nm. Most modern spectrophotometers automatically calculate the sample concentration (using the A260 reading) and the A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios.

- Concentration Range: For reliable absorbance readings, ensure the A260 value falls within the instrument's linear range, typically between 0.1 and 1.0 [16]. Samples that are too concentrated should be diluted with the same elution buffer and re-measured.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Nucleic Acid Quantification and Quality Control

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| UV-Transparent Elution Buffer (e.g., Tris-EDTA, Tris-HCl) | A low-salt buffer at neutral pH used to suspend nucleic acids, ensuring accurate spectrophotometric measurements and stable ratios [16]. |

| Fluorometric Dyes (e.g., PicoGreen for dsDNA, RiboGreen for RNA) | Dyes that bind specifically to nucleic acids, enabling highly sensitive and specific quantification, free from interference from common contaminants [5] [16]. |

| Agarose Gel | A matrix used in electrophoresis to visually assess nucleic acid integrity and confirm the presence of high-molecular-weight DNA or intact rRNA bands [5] [16]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Certified materials with known absorbance values used to check the photometric and wavelength accuracy of spectrophotometers [18]. |

Comparative Analysis of Quantification Technologies

While UV spectrophotometry is ubiquitous for its speed and simplicity, it is one of several tools available for quality control. The table below compares its performance against other common methods.

Table 3: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Quantification and Quality Assessment Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | Measures absorbance of UV light at 260 nm [5] | Simple, quick, non-destructive, provides purity ratios (A260/A280, A260/230) [5] [2] | Non-specific (cannot differentiate DNA/RNA); sensitive to contaminants; less reliable for very low or high concentrations [5] [2] |

| Fluorometry | Fluorescent dyes (e.g., PicoGreen, RiboGreen) bind specifically to nucleic acids [5] | Highly specific and sensitive; not affected by common contaminants; ideal for low-concentration samples [5] [16] [2] | Requires specific dyes and calibration; cannot provide purity ratios for salts/organics; results depend on standard curve [5] |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis | Separates nucleic acids by size using an electric field [5] [16] | Low-cost; visual assessment of integrity and degradation; confirms high molecular weight [5] [16] | Semi-quantitative at best; time-consuming and labor-intensive; not effective for very small fragments [5] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (e.g., TapeStation, Bioanalyzer) | Separates nucleic acids by size in a capillary [5] [19] | High accuracy; provides an integrity number (e.g., RINe, DIN); suitable for high-throughput [5] [19] | Expensive instrumentation; requires specialized chips/reagents; higher per-sample cost [5] |

The Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive Quality Control

For critical downstream applications like next-generation sequencing (NGS) or quantitative PCR (qPCR), relying on a single method is insufficient. A robust, multi-technique approach is recommended.

- Step 1: Rapid Assessment: Use UV spectrophotometry for an initial check of concentration and to screen for protein or salt contamination via A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios [5] [2].

- Step 2: Specific Quantification: For precise quantification, especially with low-yield samples or those with abnormal ratios, use a fluorometric assay [16]. This provides a contaminant-resistant concentration value.

- Step 3: Integrity Verification: Finally, assess sample integrity using capillary electrophoresis (providing a numerical RINe or DIN score) or agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the nucleic acids are not degraded [19] [16] [2]. A sample with good purity ratios but a poor integrity number is still unsuitable for many applications.

In conclusion, mastering the interpretation of A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios is an essential skill for any researcher working with nucleic acids. While spectrophotometry is an powerful first-line tool, it is most effective when used as part of an integrated quality control strategy that includes fluorometry and integrity analysis, ensuring that your samples are of sufficient quality to yield reliable and reproducible scientific data.

The accurate quantification of nucleic acids is a cornerstone procedure in molecular biology, essential for the success of downstream applications from quantitative PCR (qPCR) to next-generation sequencing (NGS) [5]. For decades, this fundamental task was performed using traditional cuvette-based spectrophotometers, which required relatively large sample volumes and often involved time-consuming dilutions. The advent of microvolume spectrophotometry has revolutionized this process, enabling researchers to obtain rapid concentration and purity measurements from just 1-2 µL of sample [20] [21]. This guide traces the instrumental evolution from traditional cuvettes to modern systems, with a focused comparison on leading microvolume platforms. We will objectively compare the performance of traditional systems against modern microvolume alternatives, providing experimental data and detailed methodologies to frame their capabilities within the context of DNA and RNA concentration and purity assessment for research and drug development.

Traditional Cuvette-Based Spectrophotometry

Principles and Limitations

Traditional UV-Vis spectrophotometry operates on the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorbance of light by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length of the light through the solution [5]. In cuvette-based systems, this path length is fixed, typically at 10 mm (1 cm).

- Sample Volume Requirements: These systems traditionally require large sample volumes, often ranging from 50 µL to 1 mL, depending on the cuvette type [20]. This presented a significant bottleneck for samples with limited yield, such as those from needle biopsies or laser-capture microdissection.

- Dilution Necessity: The broad dynamic range of nucleic acid concentrations often necessitates sample dilution to fall within the instrument's linear range, introducing additional steps and potential for error.

- Consumables Dependency: The requirement for cuvettes adds ongoing consumable costs and introduces risks associated with cuvette cleanliness and handling.

The limitations of traditional systems, particularly for low-volume or high-concentration samples, created a clear need for a more efficient and sample-conserving technology.

The Microvolume Revolution

Core Technological Innovation

Microvolume spectrophotometers, pioneered by systems like the NanoDrop, overcame the limitations of cuvettes through a novel sample retention system [20]. This technology leverages fiber optics and natural surface tension properties to capture and retain a small droplet of sample (0.5-2 µL) between two optical surfaces, forming a liquid column without the need for traditional containment apparatus [20]. A key advancement is the use of shorter, automatically adjusted path lengths (e.g., 0.03–1.0 mm), which prevent signal saturation and allow for the measurement of highly concentrated samples without dilution [20] [22]. This innovation dramatically expands the dynamic range of measurable concentrations.

Workflow and Practical Advantages

The microvolume workflow is significantly streamlined. A user simply dispenses a 1-2 µL droplet onto the measurement pedestal, lowers the arm, and initiates measurement, with results displayed in seconds [23]. This process eliminates the need for cuvettes and dilutions, saving both time and precious sample material. The integrated software automatically calculates nucleic acid concentration using pre-programmed algorithms and provides key purity ratios (A260/A280 and A260/A230), enabling rapid assessment of sample quality [20] [5].

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for microvolume spectrophotometer measurement, illustrating the rapid and simple process.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Microvolume Systems

Technical Specifications of Leading Platforms

The microvolume spectrophotometer market includes several key players, primarily Thermo Fisher Scientific with its NanoDrop line, DeNovix with the DS-11 Series, and Blue-Ray Biotech with the EzDrop series. The table below summarizes the key specifications for a direct comparison.

Table 1: Technical specification comparison of leading microvolume UV-Vis spectrophotometers.

| Feature | NanoDrop One | NanoDrop 2000 | DeNovix DS-11 Series | EzDrop 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Sample Volume | 1–2 µL [21] | 1–2 µL [24] | 1 µL (approx.) [22] | 1 µL [24] |

| dsDNA Dynamic Range | 0.2–27,500 ng/µL (pedestal) [21] [23] | 2–15,000 ng/µL [23] | Information Missing | Up to 20,000 ng/µL [24] |

| Wavelength Range | 190–850 nm [21] | 190–850 nm (from context) | Information Missing | 190–1000 nm [24] |

| Pathlength Control | Auto-adjusting (0.03–1.0 mm) [22] | Fixed short path | SmartPath technology (starts at 0.5mm) [22] | Low pathlength design [24] |

| Key Technology | Acclaro Sample Intelligence [21] | Standard microvolume | Bridge Testing verification [22] | Wide wavelength range [24] |

| Fluorometer Option | No (separate fluorometer models) [22] | No | Yes, integrated (on select models) [22] | Not specified |

Experimental Data on Accuracy and Precision

Objective performance comparisons often rely on measuring serially diluted samples of known concentration to assess accuracy and repeating measurements on a single sample to determine precision (reproducibility).

- Accuracy Comparison: A study comparing the EzDrop 1000, NanoDrop One, and NanoDrop 2000 using a two-fold serial dilution of a known-concentration salmon sperm DNA sample demonstrated a high degree of accuracy across all platforms. The correlation coefficients (R²) for the measured versus expected concentrations were above 0.99 for all instruments, indicating that their readings closely matched the true concentration of the analyte [24].

- Precision Comparison: A direct precision test between the EzDrop 1000 and the DS-11 involved measuring the same sample (at 2,500 ng/µL and 312 ng/µL) three times each. The reported results showed that the EzDrop 1000 exhibited a more stable Coefficient of Variation (CV value) across these replicates, suggesting better reproducibility under the tested conditions [24].

These experimental findings indicate that while newer instruments like the EzDrop and DS-11 are strong competitors, established models like the NanoDrop maintain a high standard of analytical accuracy.

Essential Protocols for Quantification and Quality Assessment

Protocol 1: Direct Absorbance Measurement with a Microvolume Spectrophotometer

This protocol is adapted from established methodologies for instruments like the NanoDrop 2000c and is universally applicable to similar microvolume systems [20].

- System Initialization: Power on the instrument and computer. Launch the associated software and select the "Nucleic Acid" application.

- Pedestal Cleaning: Pipette 2–3 µL of clean deionized water onto the lower optical pedestal. Close and then open the lever arm. Thoroughly wipe both the upper and lower optical surfaces with a clean, dry, lint-free lab wipe to remove any residue [20].

- Blank Measurement: Dispense 1–2 µL of the buffer used to suspend your sample (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water) onto the center of the lower pedestal. Close the lever arm and select "Blank" in the software. Once the measurement is complete, lift the arm and wipe both surfaces clean [20] [23].

- Sample Measurement: Choose the appropriate constant for your sample type in the software (e.g., "dsDNA" for double-stranded DNA, which uses a factor of 50) [20]. Dispense 1–2 µL of your nucleic acid sample onto the lower pedestal. Close the lever arm and select "Measure." The software will automatically display the concentration (in ng/µL) and calculate the A260/A280 and A260/A230 purity ratios.

- Post-Measurement Cleaning: After the measurement, lift the arm and thoroughly wipe both optical surfaces clean with a lint-free wipe before proceeding to the next sample.

Protocol 2: High-Sensitivity Quantitation via Fluorescence

For samples too dilute for accurate UV absorbance measurement (e.g., below 2 ng/µL), a fluorescence-based method using a dye like PicoGreen is recommended [20] [21]. This protocol can be performed on a dedicated microvolume fluorospectrometer.

- Reagent Preparation: Equilibrate the PicoGreen kit reagents and all samples to room temperature. Prepare a 1X TE buffer by diluting a 20X stock with nuclease-free water. Prepare the PicoGreen working solution according to the manufacturer's protocol. Keep all fluorescent reagents in amber or foil-wrapped tubes to protect from light [20].

- Standard and Sample Preparation: Prepare serially diluted dsDNA standards in nuclease-free tubes at 2x the final desired concentration. Aliquot 5 µL of each standard and 5 µL of each unknown sample into labeled, light-safe tubes. Add an equal volume (5 µL) of the PicoGreen working solution to each tube, mixing gently by pipetting. Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes [20].

- Instrument Measurement: Clean the pedestal surfaces with deionized water and a lint-free wipe. In the fluorospectrometer software, select the "Nucleic Acids" application and the "PicoGreen-dsDNA" option. Blank the instrument using 2 µL of 1X TE buffer. Measure 2 µL of the reference solution (1X TE + PicoGreen working solution) and then all standards to build a standard curve. Finally, measure each of your unknown samples. The software will automatically determine sample concentrations based on the standard curve [20].

Diagram 2: A decision workflow to guide the choice between absorbance and fluorescence quantification methods based on sample properties.

Data Interpretation and Purity Ratios

Regardless of the instrument, interpreting the results correctly is critical.

- Purity Ratios: The A260/A280 ratio assesses protein contamination. Pure DNA typically has a ratio of ~1.8, while pure RNA is ~2.0 [5] [23]. The A260/A230 ratio assesses contamination by salts, EDTA, or carbohydrates; a value for a "pure" nucleic acid is commonly in the range of 1.8–2.2 [20] [5]. Significantly lower values indicate contamination that may inhibit downstream applications.

- Spectral Analysis: Always examine the spectral curve. A typical pure nucleic acid sample has a smooth peak at 260 nm. Abnormal shoulders or shifts in the curve can indicate the presence of contaminants like phenol (around 270 nm) or guanidine (peak near 230 nm) [20].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Quantification.

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TE Buffer (Tris-EDTA) | A common suspension buffer for nucleic acids; provides a stable pH, while EDTA inhibits nucleases. | Often used for long-term storage of DNA. Its absorbance should be considered when used as a blank. |

| Nuclease-free Water | Purified water certified to be free of nucleases, preventing degradation of RNA and DNA samples. | The most common blanking solution for samples suspended in water. Ideal for downstream enzymatic applications. |

| PicoGreen Assay | A fluorescent dye that binds specifically to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), enabling high-sensitivity quantification. | Used for fluorometric protocols. Highly specific and sensitive for low-concentration dsDNA samples (1 pg/µL to 1,000 ng/µL) [20] [21]. |

| RiboGreen Assay | A fluorescent dye for quantifying RNA in the presence of DNA, or for total nucleic acid quantification. | Used for fluorometric protocols. Provides high sensitivity for RNA quantification [5]. |

| Pedestal Cleaning Solution | Deionized water is standard; specific reconditioning compounds are available for stubborn contaminants. | Essential for preventing cross-contamination. Detergents and isopropyl alcohol are not recommended as they can uncondition the pedestal surface [20]. |

| Lint-free Lab Wipes | For cleaning and drying the optical pedestals between measurements. | Critical for maintaining optical clarity and preventing scratches. Lint from standard wipes can interfere with measurements [20]. |

The transition from traditional cuvette-based spectrophotometers to modern microvolume systems represents a significant leap forward in efficiency and practicality for life science research. These instruments conserve precious samples, accelerate workflows, and provide a broad dynamic range that often eliminates the need for dilutions. As the experimental data shows, current market leaders like the NanoDrop One, DeNovix DS-11, and EzDrop 1000 all deliver high accuracy, with distinctions often lying in specific features like integrated fluorometry, proprietary sample intelligence software, or unique pathlength technologies.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of instrument will depend on specific application needs, required throughput, and budget. However, the underlying microvolume technology has unequivocally become the standard for nucleic acid quantification and quality assessment, enabling greater confidence and success in downstream molecular applications.

Ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometry remains a foundational technique in molecular biology for the rapid assessment of nucleic acid concentration and purity. This method leverages the intrinsic property of DNA and RNA bases to absorb light at a specific wavelength (260 nm), allowing researchers to quantify genetic material without additional labels or reagents. For scientists and drug development professionals, understanding the expected values for pure preparations is critical for downstream applications ranging from routine PCR to cutting-edge sequencing technologies. The accuracy of these spectrophotometric measurements directly influences experimental success, as impurities or incorrect quantification can compromise enzymatic reactions, skew results, and waste valuable resources [25] [26].

This guide provides a definitive comparison of the expected absorbance ratios and conversion factors for DNA and RNA, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols. Within the broader context of spectrophotometry research, we objectively examine the performance of different measurement approaches, from traditional cuvette-based systems to modern microplate readers and specialized instruments like the NanoDrop. The guidelines presented here are synthesized from manufacturer specifications, peer-reviewed validation studies, and established laboratory manuals to create an authoritative reference for life science researchers [26] [15] [27].

Fundamental Conversion Factors and Molecular Weights

Key Conversion Factors for Concentration Calculation

The concentration of nucleic acids in a solution is calculated using established conversion factors based on their absorbance at 260 nm. These factors represent the concentration (in µg/mL) that produces an absorbance of 1.0 in a 1-cm pathlength cuvette. The table below summarizes the standard conversion factors for different nucleic acid types.

Table 1: Standard conversion factors for nucleic acid quantification using A260 measurements.

| Nucleic Acid Type | Conversion Factor (µg/mL per 1 A260 unit) | Notes and Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | 50 µg/mL | Standard for dsDNA in high-salt buffers [26] [28]. |

| Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | 37 µg/mL | Applicable for oligonucleotides and denatured DNA [26]. |

| RNA | 40 µg/mL | Standard for most RNA transcripts [26]. |

It is crucial to note that these conversion factors are dependent on the solvent's ionic strength. DNA dissolved in deionized water has approximately 15% lower absorbance than in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and 23% lower absorbance than in TE buffer with saline (TES). Consequently, the effective conversion factor for dsDNA can vary from 38 µg/mL in water to 50 µg/mL in TES [27]. This underscores the importance of using the same diluent for both blanks and samples and being consistent with buffer conditions when comparing results.

Nucleotide Molecular Weights

For precise calculations, especially when working with synthetic oligonucleotides or when molar concentration is required, the molecular weights of individual nucleotides are essential. The following table provides the exact molecular weights for ribonucleotide and deoxyribonucleotide mono- and triphosphates.

Table 2: Molecular weights of nucleotides used for exact calculation of nucleic acid molecular weights [29].

| Nucleotide | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|

| Ribonucleotide Monophosphates (Avg. MW = 339.5) | |

| AMP | 347.2 |

| CMP | 323.2 |

| GMP | 363.2 |

| UMP | 324.2 |

| Deoxyribonucleotide Monophosphates (Avg. MW = 327.0) | |

| dAMP | 331.2 |

| dCMP | 307.2 |

| dGMP | 347.2 |

| dTMP | 322.2 |

The molecular weight of a single-stranded oligonucleotide can be calculated precisely using the formula: M.W. = (An x 313.2) + (Tn x 304.2) + (Cn x 289.2) + (Gn x 329.2) + 79.0, where An, Tn, Cn, and Gn are the number of each respective nucleotide, and 79.0 accounts for the 5' monophosphate [29].

Defining Purity: Expected Absorbance Ratios

The purity of nucleic acid preparations is assessed using absorbance ratios, which help identify common contaminants that can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions.

Standard Absorbance Ratios for DNA and RNA

Table 3: Expected absorbance ratios for pure DNA and RNA and interpretations of deviations [30] [26] [15].

| Absorbance Ratio | Expected Value for Pure DNA | Expected Value for Pure RNA | Indication of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 | ~1.8 | ~2.0 | Lower ratio: Potential protein or phenol contamination. Higher ratio (DNA): Indicates RNA contamination. |

| A260/A230 | 2.0 – 2.2 | 2.0 – 2.2 | Lower ratio: Contamination by chaotropic salts, carbohydrates, phenol, or EDTA. |

These ratios are a cornerstone of nucleic acid QC. A study validating NanoDrop quantification confirmed that pure DNA from standard reference material (NIST SRM 2372) consistently yields these expected ratios, establishing the method's reliability for microvolume measurements [15]. Furthermore, in DNA storage research, these ratios are critical for monitoring the integrity of retrieved DNA, ensuring that the dehydration/rehydration process does not introduce contaminants [25].

Experimental Protocols for Accurate Measurement

Validated DNA Quantification Protocol Using a Microvolume Spectrophotometer

The following protocol, adapted from a peer-reviewed validation study, ensures accurate and reproducible DNA quantification [15].

- Instrument Calibration: Initialize the spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop 2000) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Use the same solvent for the blank as the sample diluent (e.g., nuclease-free water or TE buffer).

- Sample Preparation: Dilute samples if necessary to fall within the instrument's linear range. For the NanoDrop, 1-2 µL is sufficient. For microplate readers, use a larger volume (250-300 µL) to maximize the optical pathlength and sensitivity [27].

- Measurement: Wipe the sampling pedestals clean. Apply 1 µL of blank solution to take the baseline measurement. Carefully clean the surface and apply 1 µL of sample for measurement. Perform technical replicates for reliability (n=3 is standard).

- Data Analysis: Record the concentration (in ng/µL) calculated from the A260 value and the purity ratios (A260/A280 and A260/A230). The method validation demonstrated linearity with correlation coefficients of R ≥ 0.9950 and a precision of ≤2% coefficient of variation (CV) [15].

Workflow for Nucleic Acid Quality Control

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision-making process for assessing nucleic acid quality using spectrophotometry.

Diagram 1: A logical workflow for interpreting nucleic acid concentration and purity metrics from UV spectrophotometry. Deviations from expected values flag potential contaminants that may require further sample purification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 4: Key equipment and reagents required for spectrophotometric analysis of nucleic acids.

| Item | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microvolume Spectrophotometer | Measures concentration and purity of 1-2 µL samples. | E.g., Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000. Validated for DNA quantification with high precision (% CV ≤ 2) [15]. |

| UV-Transparent Microplate | Holds samples for higher-throughput analysis in a plate reader. | E.g., Corning #3635 or Greiner #655801. Essential for microplate readers; background OD must be accounted for [27]. |

| Fluorometer (Qubit) | Provides highly specific quantification of dsDNA mass, unaffected by contaminants. | Recommended for accurate quantification before library preparation for sequencing [26]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Primary diluent for blanks and samples. | Minimizes interference. Using a consistent diluent is critical for accuracy [25] [27]. |

| Standard Reference Material DNA | Validates instrument and method performance. | E.g., NIST SRM 2372. Used in method validation to establish trueness [15]. |

| Bioanalyzer / Femto Pulse System | Assesses size distribution and integrity of nucleic acids. | Critical for verifying fragment size for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) applications [26]. |

Comparative Performance of Measurement Techniques

While UV absorbance is ubiquitous, it is one of several methods for nucleic acid quantification. The table below compares its performance with other common techniques.

Table 5: Comparison of nucleic acid quantification and quality control methods.

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV Absorbance (NanoDrop, cuvette) | Measures absorbance at 260 nm. | Fast, simple, provides purity ratios (A260/280, A260/230), requires minimal sample [15]. | Lower sensitivity; non-specific (cannot distinguish between DNA, RNA, free nucleotides); affected by chemical contaminants [26] [28]. |

| Fluorometry (Qubit) | Fluorescent dye binding specifically to dsDNA/RNA. | Highly specific for target nucleic acid, insensitive to contaminants, very sensitive [26]. | Requires standard curve; does not provide purity information; more expensive per sample. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) | Electrokinetic separation of nucleic acids by size. | Provides detailed information on size distribution and integrity (RIN/DIN) [30] [26]. | Higher cost, more complex operation, longer analysis time. |

The choice of method depends on the application. For routine checks of concentration and purity where some RNA or salt contamination is not a concern, UV absorbance is sufficient. However, for critical applications like next-generation sequencing library preparation, a combination of methods is strongly recommended: Qubit for accurate mass quantification, NanoDrop for purity screening, and Bioanalyzer for size and integrity assessment [26]. This multi-faceted QC approach ensures optimal performance in downstream enzymatic steps and maximizes sequencing success.

Advanced Considerations and Data Interpretation

Impact of Sample Characteristics

The accuracy of UV spectrophotometry can be compromised by several factors. The presence of particulate matter or air bubbles in the sample is a common cause of spurious absorbance readings. It is therefore essential to use particle-free solutions and to centrifuge samples if necessary [27]. Furthermore, the homogeneity of the sample is critical, especially for high molecular weight DNA preparations, which can be viscous and unevenly distributed, leading to inaccurate quantification [26].

As highlighted in the workflow diagram, deviations from expected purity ratios provide diagnostic power:

- An A260/A280 ratio below 1.7-1.8 for DNA often indicates contamination by proteins or phenol, which absorb strongly at 280 nm [26] [28].

- A significantly low A260/A230 ratio is a common indicator of contamination by chaotropic salts, carbohydrates, or EDTA, which absorb around 230 nm [26] [15].

- For DNA samples, an A260/A280 ratio significantly above 1.8 suggests the presence of RNA, which has a higher expected ratio [26].

Method Validation and Quality Assurance

For diagnostic service laboratories, validating the DNA quantification method is a requirement of good laboratory practices. A comprehensive validation of the NanoDrop method demonstrated excellent linearity (R ≥ 0.9950) and precision (% CV ≤ 2). The study also confirmed trueness, showing bias values lower than the Z-test with a 95% confidence level and a recovery percentage within the acceptable range of 100% ± 5% [15]. This level of validation ensures that measurements are not only precise but also accurate, forming a reliable basis for downstream molecular analyses.

From Theory to Bench: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Accurate DNA/RNA Measurement

In molecular biology research, the accuracy of DNA and RNA analysis is fundamentally rooted in the preliminary steps of sample preparation. Spectrophotometry, a cornerstone technique for quantifying nucleic acid concentration and assessing purity, is entirely dependent on the integrity of the sample presented to it. Buffer composition and dilution techniques are not merely supportive steps but are critical determinants of experimental success, influencing everything from nucleic acid stability to the accuracy of absorbance readings. This guide explores the foundational principles and optimized protocols that ensure sample preparation meets the rigorous demands of modern drug development and scientific research.

The Impact of Buffer Composition on Nucleic Acid Integrity

The buffer environment is crucial for stabilizing nucleic acids, facilitating their binding to purification matrices, and preventing degradation. Its specific chemical composition can significantly impact the yield, purity, and subsequent analytical results.

Key Buffer Components and Their Functions

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG): This neutral, water-soluble polymer creates a macromolecular crowding environment. This crowding increases the effective concentration of DNA molecules, promoting their aggregation and precipitation onto solid surfaces, such as nanoparticles used in extraction protocols [31].

- Salt Concentration (e.g., NaCl): Ions in the buffer modulate the electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged phosphate backbone of nucleic acids and positively charged surfaces. At low ionic strengths, electrostatic attraction is strong, facilitating binding. Higher salt concentrations introduce a shielding effect that can neutralize these attractive forces, potentially reducing adsorption efficiency [31].

- pH: The pH level influences the charge states of the functional groups on both the nucleic acids and the binding matrix. Optimizing the pH ensures maximum electrostatic interaction; for instance, a pH of 4 was found optimal for DNA binding to polyethyleneimine-coated iron oxide nanoparticles (PEI-IONPs) [31].

- Buffering Agents (e.g., Histidine, Tris, Citrate): These agents maintain a stable pH, which is vital for nucleic acid stability. Recent advances show that mildly acidic, histidine-containing buffers can markedly improve the room-temperature stability of siRNA-lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) by mitigating lipid oxidation and preventing the formation of RNA-lipid adducts [32].

Experimental Data: Buffer Optimization for DNA Extraction

A 2024 study systematically optimized the binding buffer for DNA extraction using PEI-IONPs. The results below demonstrate how buffer components directly affect DNA recovery metrics [31].

Table 1: Impact of Binding Buffer Composition on DNA Yield and Purity Using PEI-IONPs

| PEG-6000 Concentration | NaCl Concentration | pH | DNA Concentration (ng/μL) | A260/A280 Purity Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30% | 0 M | 4 | 34.0 ± 1.2 | 1.81 |

| 20% | 0 M | 4 | 29.5 ± 0.9 | 1.78 |

| 30% | 0.5 M | 4 | 25.1 ± 1.5 | 1.70 |

| 30% | 0 M | 7 | 20.3 ± 0.7 | 1.65 |

This data underscores that an optimized buffer consisting of 30% PEG-6000, 0M NaCl, and pH 4 yielded the highest DNA concentration and optimal purity, highlighting the delicate balance required between components [31].

Dilution Methodologies for Accurate Spectrophotometry

Precise dilution is fundamental for obtaining analyte concentrations within the detectable range of a spectrophotometer. The two primary methods, serial and independent dilution, offer different advantages and potential pitfalls.

Serial vs. Independent Dilution: A Comparative Analysis

- Serial Dilution: This process involves sequentially diluting a solution multiple times, using the diluted material from one step to prepare the next. It is efficient and conserves precious samples. However, a key drawback is that any error in an early dilution step is systematically propagated through the entire series, compromising the entire calibration curve [33] [34].

- Independent Dilution: In this method, each standard or sample is prepared by making a separate dilution directly from a single, concentrated stock solution. The primary advantage is that an error in preparing one standard does not affect the accuracy of the others. A noted disadvantage is that it can require large volumes of stock solution and solvent, and using different micropipette volumes for different standards can introduce a "kink" in the calibration curve due to varying volumetric errors [34].

Table 2: Comparison of Serial and Independent Dilution Methods

| Feature | Serial Dilution | Independent Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Step-wise dilution from the previous, less concentrated solution | Each standard is diluted directly from a single stock solution |

| Pros | Efficient use of stock solution and materials | Errors are isolated and not propagated; mistakes are more evident |

| Cons | Errors are compounded throughout the series | Can be wasteful of solvent and stock; may introduce volumetric kinks |

| Best Used For | Creating a logarithmic concentration gradient; when sample is limited | Preparing a small number of standards; when using a single micropipette volume |

Best Practices for Accurate Dilutions

- Use a Single Micropipette: Where possible, use one microsyringe or micropipette for a dilution series to avoid inconsistencies in void volume and calibration between different instruments [34].

- Maintain Solvent Consistency: The stock solution should be in the same solvent as the final standards to prevent bias from varying solvent concentrations in the absorbance reading [34].

- Check-Weigh Volumes: For the highest accuracy, particularly at very low concentrations (ng/μL or pg/μL), check-weighing the masses of the added solute and solvent can correct for inaccuracies in volumetric measurements [34].

Integrated Workflow: From Sample to Reliable Spectrophotometric Data

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow that integrates optimized buffer use and precise dilution to ensure the integrity of nucleic acid analysis via spectrophotometry.

Essential Reagents and Materials for Nucleic Acid Workflows

A well-equipped lab relies on specific reagents and kits tailored for different sample types and downstream applications.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| PEI-IONP Binding Buffer [31] | Optimized buffer (30% PEG, 0M NaCl, pH 4) for high-efficiency DNA binding to magnetic nanoparticles | DNA extraction from biological fluids (e.g., blood) for diagnostics and genomics. |

| Phenol-Chloroform Reagents [35] [36] | Organic extraction to separate DNA, RNA, and proteins into different phases. | Traditional, cost-effective nucleic acid isolation; often used for challenging samples. |

| Silica-Based Kits [35] | Bind nucleic acids under high-salt conditions; elute under low-salt conditions. | Plasmid, genomic DNA, and RNA purification via spin columns or high-throughput plates. |

| Magnetic Bead Kits [35] | Paramagnetic beads bind nucleic acids for magnetic separation and washing. | Automated, high-throughput DNA/RNA extraction (e.g., MagMAX kits). |

| TRIzol Reagent [36] | Monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for effective cell lysis. | Simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA, and proteins from a single sample. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized DNA Extraction Using PEI-IONPs

This protocol, adapted from recent research, is designed for maximum DNA recovery from biological fluids like blood [31].

- Synthesis of PEI-IONPs: Iron oxide nanoparticles are synthesized via co-precipitation of Fe(II) and Fe(III) salts in an alkaline medium under an inert atmosphere, with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) as a stabilizer. The particles are then functionalized by coating with branched polyethyleneimine (PEI, 25 kDa) [31].

- Sample Lysis: Mix the biological sample (e.g., blood) with a lysis buffer containing a detergent (e.g., Triton X-100) and Proteinase K to disrupt cells and degrade proteins.

- DNA Binding: Add the PEI-IONPs to the lysate along with the optimized binding buffer (30% PEG-6000, 0M NaCl, pH 4). Incubate with agitation to allow DNA to bind to the nanoparticles via electrostatic interactions [31].

- Magnetic Separation: Place the tube on a strong magnet. The nanoparticles (with bound DNA) will be attracted to the magnet. Carefully remove and discard the supernatant.

- Washing: Resuspend the pellet in a wash buffer (often ethanol-based) to remove impurities. Repeat the magnetic separation and supernatant removal.

- Elution: Resuspend the nanoparticle pellet in a low-salt buffer (e.g., Tris-EDTA) or nuclease-free water at room temperature. The change in ionic strength and pH releases the pure DNA, which is then separated from the nanoparticles via magnetic separation [31].

Protocol 2: Accurate Dilution for Spectrophotometric Calibration

This protocol outlines best practices for preparing standards, crucial for building a reliable calibration curve.

- Planning: Determine the required concentration range for your standards. Plan the dilution scheme, aiming to use a single, appropriately sized micropipette for all transfers to minimize volumetric error [34].

- Preparation: Allow all solutions (stock and solvent) to reach room temperature. Ensure all volumetric flasks or tubes are clean.

- Independent Dilution Method:

- For each standard, pipette a precise volume of the stock solution directly into a volumetric flask.

- Dilute to the mark with the appropriate solvent (the same as the stock's solvent). Mix thoroughly [34].

- Serial Dilution Method:

- Prepare the first standard by diluting the stock solution.

- Take a precise volume from this first dilution to prepare the second standard.

- Continue this process sequentially to create the entire concentration series [33].

- Blank Preparation: Prepare a blank solution containing only the solvent used to dissolve the analyte. This blank is essential for calibrating the spectrophotometer to zero absorbance before measuring standards and unknowns [37].

The journey to reliable and reproducible spectrophotometric data in nucleic acid research is paved with meticulous attention to sample preparation. As demonstrated, the choice of buffer components like PEG, NaCl, and pH can dramatically influence DNA binding efficiency and purity. Furthermore, the selection between serial and independent dilution strategies involves a critical trade-off between efficiency and error control. By integrating optimized buffers and rigorous dilution practices into a standardized workflow, researchers can significantly enhance the accuracy of DNA and RNA quantification, thereby ensuring the success of downstream applications in molecular biology, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

In spectrophotometric analysis for nucleic acid research, the process of "blanking" the instrument is a critical foundational step. A blank is an analyte-free sample, typically the solvent in which the nucleic acid is dissolved, used to calibrate the spectrophotometer and establish a baseline absorbance reading. The primary function of the blank is to account for the absorbance contributed by the cuvette, the solvent, and any reagents present, thereby ensuring that the subsequent sample measurement reflects only the absorbance of the DNA or RNA itself. Proper blanking is indispensable for obtaining accurate and reproducible concentration and purity measurements, which are crucial for the success of downstream molecular applications such as PCR, sequencing, and cloning [38].

This article provides a detailed, step-by-step workflow for blanking and sample measurement, objectively comparing the performance of single beam and double beam spectrophotometers. The protocols and data presented are framed within the context of DNA and RNA concentration and purity assessment, a common requirement in biopharmaceutical and academic research settings.

Single Beam vs. Double Beam Spectrophotometers: A Technical Comparison

The fundamental difference between single and double beam spectrophotometers lies in their optical layouts, which directly impacts the blanking workflow and data stability.

- Single Beam Design: A single beam instrument utilizes one light path. The blank measurement is taken first by placing the blank solution in the light path. The instrument is calibrated to this reference, and the sample is then measured separately. This design measures the ratio of the incident beam energy to the transmitted beam energy by taking sequential readings [39] [40].

- Double Beam Design: A double beam instrument splits the incident light into two beams: one passes through the sample and the other simultaneously passes through the blank reference. The detector then records the ratio of the two beams in real-time [39] [40].

The table below summarizes the key performance differences relevant to nucleic acid quantification:

Table 1: Comparison of Single Beam and Double Beam Spectrophotometers

| Feature | Single Beam Spectrophotometer | Double Beam Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Path | Single path; sequential measurement of blank and sample [40] | Two paths; simultaneous measurement of blank and sample [39] |

| Blanking Workflow | Requires manual calibration with blank before sample measurement [40] | Real-time, continuous correction against the blank during sample measurement [39] |

| Correction for Instability | Does not compensate for drift in lamp intensity or electronics between blank and sample readings [40] | Actively corrects for fluctuations in lamp intensity, stray light, and electronic noise [39] [40] |

| Typical Sensitivity | Higher light throughput due to fewer optical components [39] [40] | Slightly reduced light throughput due to the beam splitter [39] |

| Typical Stability & Reliability | Lower; susceptible to drift after initial blanking [40] | Higher; provides more stable and reliable absorbance readings [39] [40] |

| Cost | Generally more cost-effective [39] | Higher cost due to more complex optics [39] |

The following diagram illustrates the operational workflows of both instruments, highlighting how the blank is integrated into the measurement process.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure: Blanking and Sample Measurement

This protocol is applicable to both cuvette-based and microvolume spectrophotometers. The example assumes the use of a Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, a common solvent for nucleic acids.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Power On and Initialize: Turn on the spectrophotometer and allow the lamp to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer (typically 15-30 minutes) to ensure stable light output [41].

- Select Application: On the instrument's software, select the "Nucleic Acid" application. For DNA, choose the "dsDNA" option.

- Clean the Measurement Surface:

- For cuvette instruments: Use a lint-free lab wipe to clean the exterior of a spectrophotometer-grade quartz cuvette.

- For microvolume instruments: Pipette 1-2 µL of deionized water onto the lower measurement pedestal. Lower the arm, then raise it and wipe both pedestals thoroughly with a dry, lint-free lab wipe [41] [42].

- Load the Blank:

- Pipette the blank solution (e.g., TE buffer) into a clean cuvette or directly onto the measurement pedestal. The volume must be sufficient to form a stable liquid column (microvolume) or fill the cuvette.

- Ensure no air bubbles are present, as they can scatter light and cause inaccurate readings.

- Perform the Blank Measurement:

- Insert the cuvette into the compartment or close the arm on the microvolume pedestal.

- Execute the "Blank," "Zero," or "Reference" command in the software. The instrument will measure the absorbance of the blank and set it as the baseline, effectively subtracting its contribution from subsequent sample readings [38] [42].

- Clean the System: After blanking, remove the blank solution. For cuvettes, rinse thoroughly with deionized water. For microvolume systems, wipe the pedestals clean with a lint-free wipe.

- Load and Measure the Sample:

- Pipette your nucleic acid sample into a clean cuvette or onto the cleaned pedestal.

- Initiate the measurement. The instrument will display the absorbance values at the selected wavelengths (e.g., A260, A280, A230).

- For microvolume systems, clean the pedestals immediately after measurement to prevent sample carryover [42].

- Data Recording: Record the concentration (calculated from A260) and the purity ratios (A260/A280 and A260/A230). The software typically calculates these values automatically.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials required for accurate spectrophotometric analysis of nucleic acids.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvent (e.g., TE Buffer, Nuclease-free Water) | Serves as the blank solution and diluent for nucleic acid samples. Its high purity ensures low background absorbance, which is critical for accurate baseline calibration [38]. |

| Spectrophotometer Cuvettes | Specialized quartz cuvettes are transparent to UV light and are used to hold samples in traditional spectrophotometers. Their optical quality is vital for measurement accuracy [38]. |

| Lint-Free Laboratory Wipes | Essential for cleaning cuvette exteriors and microvolume pedestals without leaving fibers, which can scatter light and introduce significant errors [42]. |

| Certified DNA/RNA Standards | Solutions with known concentrations are used for periodic validation and quality control of the spectrophotometer to ensure the instrument is providing accurate readings over time. |

Data Interpretation and Quality Control

Assessing Nucleic Acid Purity and Concentration

Following measurement, the absorbance data is used to determine the concentration and purity of the nucleic acid sample.

- Concentration: The concentration of double-stranded DNA is calculated using the formula: Concentration (µg/mL) = A260 reading × 50 (dilution factor). For RNA, the conversion factor is 40 [42].

- Purity Ratios: The ratios of absorbance at different wavelengths indicate the presence of common contaminants.

- A260/A280 Ratio: This is the primary indicator of protein contamination. Pure DNA typically has a ratio of ~1.8, while pure RNA has a ratio of ~2.0. A ratio significantly lower than expected suggests contamination with proteins or phenol [14] [42].

- A260/A230 Ratio: This is a secondary indicator of contamination by organic compounds such as chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine thiocyanate), phenol, or EDTA. A pure sample generally has a ratio in the range of 2.0–2.2. A low A260/A230 ratio indicates the presence of such contaminants [14].

Table 3: Interpretation of Nucleic Acid Absorbance Ratios and Concentrations

| Parameter | Ideal Value (DNA) | Ideal Value (RNA) | Deviation & Probable Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 Ratio | ~1.8 [14] | ~2.0 [14] | Low Value (<1.6-1.8): Protein or phenol contamination [14] [41]. High Value (>2.0-2.2): RNA contamination in DNA samples, or degradation of RNA [41]. |

| A260/A230 Ratio | 2.0 - 2.2 [14] | 2.0 - 2.2 [14] | Low Value (<2.0): Contamination with salts, EDTA, carbohydrates, or residual phenol [14] [42]. |

| Concentration Calculation | A260 × 50 µg/mL × Dilution Factor [42] | A260 × 40 µg/mL × Dilution Factor [42] | Inaccurate Concentration: Improper blanking, use of incorrect conversion factor, or significant contamination affecting A260 absorbance. |

Instrument Selection Guide for Specific Research Needs

The choice between a single beam and a double beam instrument depends on the specific requirements of the research project.