Southern Blotting: A Definitive Guide to DNA Sequence Detection for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on Southern blotting, a foundational technique for specific DNA sequence detection.

Southern Blotting: A Definitive Guide to DNA Sequence Detection for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on Southern blotting, a foundational technique for specific DNA sequence detection. It covers core principles and the historical context of the method, details a step-by-step modern workflow including non-radioactive detection, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The content also validates the technique's ongoing relevance through a comparative analysis with PCR and next-generation sequencing, highlighting its critical applications in clinical diagnostics, genotyping, and cell line characterization.

The Foundation of Southern Blotting: Principles, History, and Core Concepts

Southern blotting, a seminal technique developed by Edwin Southern in 1975, revolutionized molecular biology by enabling specific detection of DNA sequences within complex samples. This method, which involves the transfer of electrophoretically separated DNA fragments to a membrane for hybridization with a labeled probe, remains a foundational procedure for analyzing gene structure, copy number, and organization. While newer technologies like PCR and next-generation sequencing have replaced it for many routine applications, Southern blotting retains unique utility for characterizing large genomic rearrangements and determining methylation status. This application note details the fundamental principles, provides optimized protocols, and contextualizes the ongoing relevance of Southern blotting in modern genomic research.

Southern blotting is a versatile molecular biology technique designed for the detection of specific DNA sequences within DNA samples. The method was invented by the British biologist Edwin Southern in 1975, from whom it derives its name [1] [2]. The core principle involves the identification of specific DNA fragments through hybridization—the process where complementary nucleotide sequences pair to form double-stranded molecules. This is achieved by using a labeled DNA probe that seeks out and binds to its complementary sequence on a membrane containing the target DNA fragments [1] [2].

The significance of Southern blotting lies in its ability to provide information not readily obtainable through other methods. It can determine the number of copies of a particular gene present in a genome, detect gene rearrangements, and identify specific DNA fragments for cloning purposes [2]. Although the technique has been largely superseded by PCR-based methods for many routine applications in clinical settings like the NHS Genomic Medicine Service, it retains important niche applications, particularly for diagnosing conditions caused by large expansions of tandemly repeated DNA sequences and for determining DNA methylation status [3].

The technique's name inspired a geographical naming convention for similar blotting methods: Northern blotting for RNA detection, Western blotting for protein detection, and even Southwestern blotting for DNA-protein interactions [2] [4].

Fundamental Methodology

The Southern blotting procedure consists of several sequential steps, each critical to the success of the experiment.

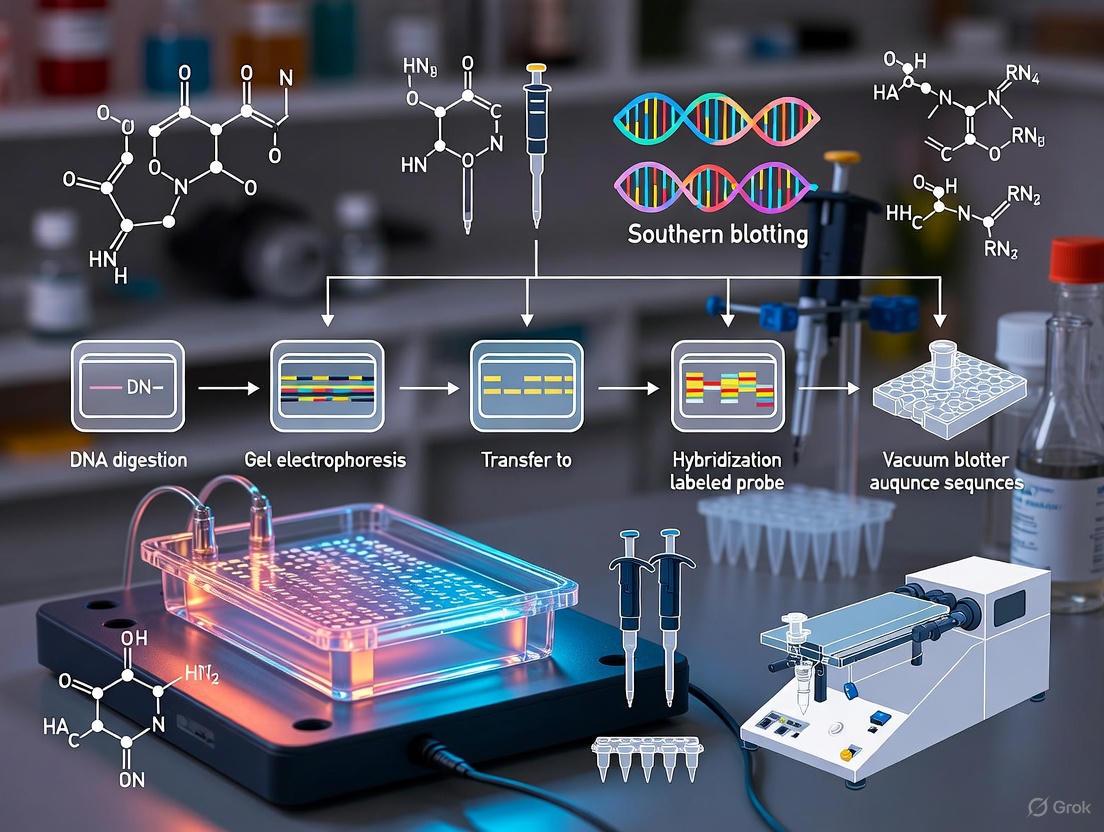

The diagram below illustrates the comprehensive Southern blotting workflow:

Key Procedural Steps

DNA Preparation and Digestion

The process begins with the extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from biological samples (tissues, cells, or blood). For complex genomic DNA, typically 5-10μg is required to ensure adequate signal detection [5]. The DNA is then digested into smaller fragments using restriction endonucleases, with complete digestion being crucial to avoid ambiguous results. For genomic DNA, digestion often requires an excess of enzyme (5-10×) and incubation overnight to ensure complete fragmentation [5] [4].

Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer

The digested DNA fragments are separated by size using agarose gel electrophoresis (typically 0.8%-1.0% agarose), which allows visualization of the fragmentation pattern [1] [6]. Following separation, the DNA is denatured into single strands using alkaline treatment, making it accessible for hybridization [6] [4]. The DNA fragments are then transferred from the gel onto a solid membrane (nitrocellulose or nylon) using capillary action, vacuum, or electrophoretic transfer [1] [6]. Capillary transfer, the original method, uses a stack of dry absorbent paper to draw transfer buffer through the gel and membrane, depositing the DNA onto the membrane surface [6] [5].

Hybridization and Detection

The membrane-bound DNA is fixed through baking or UV crosslinking, then incubated with a prehybridization solution containing blocking agents (such as Denhardt's solution or salmon sperm DNA) to minimize nonspecific probe binding [6] [4]. A labeled probe—complementary to the target sequence—is then hybridized to the membrane under controlled conditions. After hybridization, stringent washing removes non-specifically bound probes, and the specifically bound probe is detected through methods appropriate to its label (autoradiography for radioactive probes, chemiluminescence or colorimetry for non-radioactive alternatives) [1] [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful Southern blotting requires carefully selected reagents and materials, each serving specific functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Southern Blotting

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction Endonucleases | Cut DNA at specific sequences to generate defined fragments | Select enzymes based on target gene structure; use excess (5-10×) for complete digestion [5] |

| Agarose | Matrix for size-based separation of DNA fragments | Concentration (0.8-2.0%) determines resolution range for different fragment sizes [5] |

| Nylon/Nitrocellulose Membrane | Solid support for immobilized DNA | Nylon membranes offer superior durability and DNA binding capacity [1] |

| Transfer Buffer (20× SSC/SSPE) | Medium for capillary transfer of DNA from gel to membrane | Maintains ionic strength necessary for efficient DNA transfer [6] [4] |

| Blocking Agents | Reduce nonspecific probe binding | Denhardt's solution, salmon sperm DNA, or commercial blocking reagents [4] |

| Labeled DNA Probes | Hybridize to and detect specific target sequences | May be radioactive (³²P) or non-radioactive (digoxigenin, biotin) [1] |

| Hybridization Buffers | Create optimal environment for probe-target binding | PerfectHyb Plus offers optimized hybridization in 1-2 hours [4] |

Current Applications and Comparative Analysis

Contemporary Applications in Research and Diagnostics

Despite being developed nearly five decades ago, Southern blotting maintains relevance in specific research and diagnostic contexts:

Detection of Large Tandem Repeat Expansions: Southern blotting remains valuable for diagnosing disorders caused by expanded repetitive sequences (e.g., myotonic dystrophy type 1 and fragile X syndrome), as it can size fragments too large for PCR amplification [3].

DNA Methylation Analysis: Using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes, Southern blotting can determine the methylation status of DNA regions, providing clinically relevant information for conditions like fragile X syndrome where methylation correlates with gene silencing [3].

Gene Copy Number Verification: Southern blotting provides a direct method for determining transgene copy number in genetically modified organisms, as demonstrated in recent studies of GM crops [7].

Gene Rearrangement Studies: The technique detects chromosomal rearrangements and translocations in cancer cells, such as immunoglobulin gene rearrangements in lymphomas [2].

Comparative Analysis with Modern Techniques

Recent research directly compares Southern blotting with contemporary molecular analysis methods. A 2024 systematic comparison evaluated Southern blotting (SB), quantitative PCR (qPCR), digital PCR (dPCR), and paired-end whole-genome sequencing (PE-WGS) for determining gene copy numbers in transgenic plants [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Gene Copy Number Analysis Techniques

| Method | Accuracy for Single-Copy Genes | Accuracy for Multi-Copy Genes | DNA Requirement | Technical Expertise | Cost Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Blotting | Accurate [7] | Less accurate; often underestimates due to complex arrangements [7] | Substantial amount [7] | High technical skills required [7] | Relatively low reagent costs [7] |

| qPCR | Accurate [7] | Struggles with high-copy genes due to resolution limits [7] | Significantly less [7] | Understanding of primer design and qPCR setup [7] | Medium cost with moderate reagent expense [7] |

| dPCR | Accurate [7] | High accuracy due to partitioning capability [7] | Tolerant of DNA degradation [7] | Moderate expertise required [7] | Higher due to equipment costs [7] |

| PE-WGS | Accurate [7] | Precise quantification through adequate coverage [7] | Substantial amount [7] | Significant bioinformatics expertise [7] | Most expensive option [7] |

This comparative research highlights that while all four techniques can accurately quantify single-copy genes, significant discrepancies emerge for multi-copy genes [7]. Southern blotting often underestimates multi-copy genes due to complex arrangements like tandem repeats, while dPCR and PE-WGS provide more accurate quantification in these scenarios [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Genomic DNA Digestion and Electrophoresis

DNA Digestion: Set up restriction digests containing 5-10μg genomic DNA, appropriate restriction enzyme buffer, and 5-10× excess of restriction enzyme(s) in a total volume of 50-100μL. Incubate at 37°C overnight for complete digestion [5]. For complex genomic DNA, adding half the enzyme at the beginning and the remainder after several hours prevents enzyme "exhaustion" [5].

Gel Electrophoresis: Prepare a 0.8% agarose gel in 1× TAE or TBE buffer. Load digested DNA alongside appropriate molecular weight markers. Electrophorese at 1-5 V/cm until adequate separation is achieved [1] [5]. For genomic DNA, longer gels and extended run times improve resolution of similarly sized fragments.

Gel Staining and Documentation: Stain gel with ethidium bromide (0.5μg/mL) or alternative DNA stain and photograph under UV light with a ruler for size reference [6].

DNA Denaturation and Membrane Transfer

Denaturation: sequentially incubate the gel with gentle agitation in:

Capillary Transfer:

- Create a transfer stack with a glass plate bridging a reservoir containing 20× SSC buffer [6].

- Place three sheets of Whatman paper saturated with 20× SSC on the platform to form a "wick" [6].

- Place the gel on the wick, ensuring no air bubbles between layers.

- Place a pre-wetted nylon membrane (cut to gel size) on top of the gel.

- Add three more sheets of filter paper on the membrane, followed by a stack of absorbent paper towels (5-8cm high).

- Place a glass plate and 400-800g weight on top and allow transfer to proceed for 12-24 hours [6] [5].

DNA Fixation: After transfer, rinse membrane briefly in 2× SSC, air dry, and UV-crosslink (for nylon membranes) or bake at 80°C for 2 hours to permanently fix DNA [6] [4].

Hybridization and Detection

Prehybridization: Place membrane in hybridization tube with prewarmed prehybridization solution (e.g., 6× SSC, 0.5% SDS, 5× Denhardt's solution, and 100μg/mL denatured salmon sperm DNA) [5] [4]. Incubate with rotation at appropriate temperature (typically 60-68°C) for 4-6 hours [6].

Probe Preparation and Hybridization: Denature labeled probe (25-50ng for non-radioactive probes) by heating to 95°C for 5 minutes, then immediately cool on ice. Add denatured probe to fresh hybridization buffer, discard prehybridization solution from tube, and add probe/hybridization solution to membrane. Hybridize with rotation for 12-16 hours at appropriate temperature [6].

Post-Hybridization Washes: Perform sequential washes to remove non-specifically bound probe:

Signal Detection: For non-radioactive detection systems:

- Incubate membrane in blocking buffer (e.g., 1% blocking reagent in maleic acid buffer) for 30-60 minutes [6].

- Incubate with antibody conjugate (e.g., anti-digoxigenin-AP) for 30 minutes.

- Wash membrane to remove unbound antibody.

- Incubate with appropriate substrate (NBT/BCIP for colorimetric detection or CDP-Star for chemiluminescence) [6].

- For chemiluminescent detection, expose membrane to X-ray film or capture with digital imaging system.

Critical Technical Considerations

Factors Influencing Hybridization Efficiency

Several parameters significantly impact the specificity and sensitivity of Southern hybridization:

- Temperature: Optimal hybridization temperature is typically 20-25°C below the calculated Tm (melting temperature) of the probe-target duplex. Higher temperatures increase stringency but may reduce sensitivity [1].

- Ionic Strength: Hybridization rate increases with salt concentration due to neutralization of phosphate backbone charges. Low salt concentrations reduce hybridization efficiency [1].

- Probe Concentration: Higher probe concentrations increase hybridization rate but may elevate background signal. Typically 5-25ng/mL for DNA probes is optimal [6].

- Time: Hybridization is typically performed overnight for complex genomes, but shorter periods (2-4 hours) may suffice for high-copy targets with optimized buffers [4].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- High Background Signal: Can result from insufficient blocking, inadequate washing, or probe concentration too high. Increase blocking agent concentration, perform more stringent washes, or reduce probe concentration [6].

- Weak or No Signal: May indicate insufficient target DNA, inefficient transfer, probe degradation, or excessive washing. Verify DNA quantification, check transfer efficiency using gel staining after transfer, and ensure probe integrity [6].

- Bands Appear Smeared: Often caused by incomplete restriction digestion, DNA degradation, or overloading of gel wells. Ensure complete digestion with adequate enzyme, use high-quality DNA, and avoid overloading [5].

Southern blotting remains an important technique in the molecular biologist's toolkit, particularly for applications requiring direct visualization of DNA fragments without amplification. While largely superseded by PCR-based methods for routine analysis, its ability to characterize large structural variations, determine transgene copy number, and assess methylation status ensures its continued relevance in specialized research and diagnostic contexts. The detailed protocols and comparative analysis provided here offer researchers a comprehensive resource for implementing this classic technique, with understanding of both its capabilities and limitations relative to modern genomic analysis methods. As the 2024 comparative study demonstrates, methodological choice should be guided by specific experimental needs rather than technological novelty alone [7].

This application note details the seminal contributions of Professor Sir Edwin Southern, whose invention of the Southern blot in 1975 fundamentally transformed molecular biology. We explore the historical context, underlying principles, and detailed methodology of this technique, which enabled for the first time the specific detection of DNA sequences within complex genomes. Framed within a broader thesis on DNA sequence detection research, this document provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource, including modernized protocols, key reagent solutions, and data on the technique's enduring applications in genetics and molecular diagnostics.

The 1970s presented a significant challenge in molecular biology: the inability to identify specific DNA sequences within the vast complexity of an entire genome. Existing techniques could separate DNA fragments by size but lacked the specificity to pinpoint individual genes or sequences of interest. It was within this context that Edwin Southern, working at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Mammalian Genome unit in Edinburgh, devised a revolutionary method [8]. First published in 1975, the Southern blot technique combined three key innovations: restriction enzymes for cutting DNA, gel electrophoresis for size separation, and a blotting-transfer method to immobilize DNA for hybridization analysis [9].

The technique's impact was immediate and profound, allowing scientists to discern single-copy eukaryotic genes for the first time [8]. Its influence is further evidenced by the fact that it inadvertently established a naming convention for subsequent biomolecular blotting techniques—Northern (RNA), Western (protein), and Eastern (post-translational modifications)—as a pun on Southern's name [9] [10]. Southern's work, for which he received the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research in 2005, laid the essential methodological groundwork for the fields of genomics and molecular diagnostics [11].

The Southern Blot Methodology: Principles and Workflow

The core principle of Southern blotting is the separation of DNA fragments by gel electrophoresis followed by their identification through hybridization with a labeled, sequence-specific probe [12]. The process creates a permanent replica of the electrophoresis gel on a solid membrane, facilitating robust hybridization analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol is adapted from modernized laboratory procedures [12] [13] [14].

I. DNA Digestion and Gel Electrophoresis

- DNA Digestion: Incubate 10 µg of high-quality genomic DNA with an appropriate restriction enzyme (e.g., 5-10 units per µg DNA) in the recommended buffer at 37°C for a minimum of 2 hours; for complex genomic DNA, overnight digestion is standard [14]. The goal is complete digestion to ensure clear, reproducible fragments.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load the digested DNA onto a 0.5-1.2% agarose gel submerged in 1X TBE or TAE buffer. Include a DNA molecular weight ladder for size reference. Electrophorese at 1-10 V/cm until adequate separation is achieved. Visualize the DNA under UV light after staining with ethidium bromide to confirm digestion and separation [12] [13].

II. Gel Pretreatment and Blotting

- Depurination (Optional): For fragments larger than 15 kb, incubate the gel in 0.25 M HCl for 15 minutes with gentle shaking. This acid treatment breaks large DNA into smaller, more transferable pieces [9] [12].

- Denaturation: Soak the gel in a denaturing solution (e.g., 1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaOH) for 20-30 minutes. This process converts double-stranded DNA into single strands, a prerequisite for subsequent probe hybridization [9] [14].

- Neutralization: Immerse the gel in a neutralizing solution (e.g., 1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.0-7.5) for 20-30 minutes to prepare the gel for the transfer buffer [12] [14].

- Capillary Transfer:

- Assemble a transfer stack as illustrated in Figure 1. A reservoir is filled with 20X SSC or SSPE transfer buffer.

- A platform is placed in the reservoir and covered with a wick (e.g., Whatman 3MM paper) saturated with transfer buffer.

- The gel is placed on the wick, and any surrounding exposed wick is sealed with plastic wrap to prevent solvent short-circuiting.

- A pre-wetted nylon membrane (slightly larger than the gel) is carefully placed on top of the gel, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped.

- Several sheets of pre-wetted filter paper are placed on the membrane, followed by a stack of dry paper towels (4-6 cm high).

- A glass plate and a weight (~0.2-0.4 kg) are placed on top. Capillary action will draw the buffer through the gel, carrying the DNA and depositing it onto the membrane over 12-24 hours [12] [14].

III. Immobilization, Hybridization, and Detection

- Immobilization: After transfer, recover the membrane. For nylon membranes, UV cross-linking is used to covalently bind the DNA to the membrane. Alternatively, nitrocellulose membranes require baking at 80°C for 2 hours under vacuum [9] [14].

- Pre-hybridization: Place the membrane in a heat-sealable bag or hybridization tube with a pre-hybridization buffer (e.g., PerfectHyb Plus) containing blocking agents (like Denhardt's solution or salmon sperm DNA) at 42-65°C for 1-4 hours. This step blocks non-specific binding sites on the membrane to reduce background noise [12] [14].

- Hybridization: Replace the pre-hybridization buffer with fresh hybridization buffer containing the denatured, labeled probe. Incubate with continuous agitation at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 65°C for DNA probes) for 2 hours to overnight [13] [14].

- Washing and Detection:

- Washing: Perform a series of stringency washes to remove unbound and partially bound probe. Start with low-stringency washes (e.g., 2X SSC, 0.1% SDS) and progress to high-stringency washes (e.g., 0.1X SSC, 0.1% SDS at 65°C) [13].

- Detection: Visualize the hybridized probe based on its label. For radiolabeled probes, expose the membrane to X-ray film or a phosphorimager screen. For chemiluminescent labels, incubate with the appropriate substrate and expose to film [12] [13].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural stages of the Southern blot protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful Southern blotting relies on a suite of specific reagents and equipment. The table below catalogues the essential components and their functions within the protocol.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Southern Blotting

| Item | Function & Role in the Protocol | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | Sequence-specific endonucleases that fragment genomic DNA at defined sites, generating a reproducible fragment pattern. | EcoRI, HindIII; supplied with specific reaction buffers [13]. |

| Agarose Gel | Porous matrix that separates DNA fragments based on molecular size under an electric field. | 0.5-1.2% concentration; higher percentages resolve smaller fragments [12]. |

| Nylon Membrane | Positively charged solid support that binds negatively charged DNA fragments after transfer, creating a permanent blot. | BrightStar-Plus membranes; preferred over nitrocellulose for durability and higher DNA binding capacity [9] [13]. |

| Transfer Buffer | Ionic solution (e.g., SSC) used in capillary action to carry DNA from the gel onto the membrane. | 20X Saline Sodium Citrate (SSC) is standard [14]. |

| Labeled Probe | A defined, single-stranded DNA/RNA fragment complementary to the target sequence; its label enables detection. | Can be radiolabeled (²³P) or non-radioactive (biotin, digoxigenin) [9] [13]. |

| Hybridization Buffer | A solution optimized to promote specific binding between the probe and its target on the membrane while minimizing non-specific background. | ULTRAhyb or PerfectHyb Plus; contains salts, buffers, and blocking agents [13] [14]. |

Applications and Impact in Modern Research

Southern blotting remains a powerful tool with well-defined applications in both research and clinical diagnostics, despite the advent of PCR and next-generation sequencing.

Table 2: Enduring Applications of Southern Blotting

| Application Category | Specific Use Case | Technical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Mapping & Characterization | Determining gene copy number and identifying gene families [9]. | The intensity of the hybridization signal is proportional to the number of target sequences, allowing for gene quantification. |

| Mutation & Polymorphism Analysis | Detecting insertions, deletions, rearrangements, and point mutations that alter restriction sites (RFLP analysis) [9] [15]. | Altered restriction sites change the size of the DNA fragments detected by the probe, revealing sequence variations. |

| DNA Methylation Studies | Identifying methylated cytosine sites in specific genes [9]. | Uses methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (e.g., HpaII) whose cutting activity is blocked by methylated bases, yielding different fragment patterns. |

| Diagnostic & Forensic Science | Diagnosis of hereditary diseases (e.g., haemoglobinopathies), facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), and genetic fingerprinting [9] [15]. | Provides a direct, gel-based assessment of gene structure, capable of detecting large rearrangements and confirming integrations. |

Technical Considerations and Evolution

Limitations and Troubleshooting

The technique's main limitations include its requirement for a relatively large amount of high-quality DNA, its multi-step and time-consuming nature (often 2-3 days), and the use of hazardous materials (radioactivity, ethidium bromide) [9]. Modern solutions involve using sensitive non-radioactive detection kits (e.g., BrightStar BioDetect) and optimized hybridization buffers that can reduce hybridization time to just 2 hours [13].

Southern's Lasting Legacy: From Blots to Microarrays

The conceptual framework of Southern blotting—immobilizing nucleic acids on a solid support for parallel interrogation—directly inspired later technological revolutions. Edwin Southern himself was a key figure in this transition, founding Oxford Gene Technology and securing foundational patents for DNA microarray technology [16] [11]. This innovation allowed for the simultaneous expression monitoring of thousands of genes, a direct conceptual descendant of the blotting principle applied on a miniaturized, massive scale.

Southern blotting stands as a testament to methodological innovation in molecular biology. Conceived by Edwin Southern to solve a specific problem in gene analysis, its core principles of separation, transfer, and specific hybridization have proven to be remarkably durable and influential. While newer techniques may offer higher throughput for specific applications, the Southern blot remains a gold standard for the direct, size-based analysis of specific DNA sequences, particularly for validating gene copy number, large rearrangements, and integration events. Its historical and technical legacy continues to underpin modern genomic analysis, cementing Sir Edwin Southern's status as a pivotal figure in the field.

This document details the core experimental components—restriction enzymes, gel electrophoresis, and capillary transfer—that form the foundation of the Southern blotting technique. Southern blotting, developed by Edward M. Southern in the 1970s, is a seminal molecular biology method for detecting specific DNA sequences within a complex mixture, providing critical information on gene structure, organization, and methylation status [17] [18]. While newer technologies have replaced it for some high-throughput applications, Southern blotting remains indispensable for applications requiring accurate sizing of large DNA fragments, such as tandem repeat expansions in genetic disorders like myotonic dystrophy and fragile X syndrome, and for assessing DNA methylation [3]. The protocols herein are framed within a research context aimed at validating genomic integrity following genome editing, providing detailed methodologies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Component 1: Restriction Enzymes

Restriction enzymes, also known as restriction endonucleases, are bacterial-derived proteins that recognize and cut DNA at specific palindromic sequences, serving as the foundation for fragmenting genomic DNA prior to separation and analysis [19]. Their precise activity is the first critical step in generating a definable fragment pattern for downstream hybridization.

Key Principles and Applications

Restriction enzymes function as molecular scissors, enabling the analysis of genomic structure. In the context of Southern blotting for genome editing validation, they are used to digest genomic DNA into fragments of predictable sizes, which, when probed, can reveal the structure of a locus and confirm the success of an edit [20].

Key applications include:

- Gene Mapping and Mutation Detection: Identifying genetic variations and mutations by analyzing changes in fragment lengths (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms, RFLPs) [19].

- Diagnostic Testing: Detecting genetic mutations linked to diseases, such as large repeat expansions in myotonic dystrophy type 1 or fragile X syndrome [3] [19].

- Methylation Analysis: Using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes that cannot cut methylated DNA to assess the epigenetic status of genomic regions [3].

Quantitative Data on Restriction Enzymes

Table 1: Common Restriction Enzymes and Their Characteristics

| Enzyme Name | Recognition Sequence (5'→3') | Standard Incubation Temperature | Common Applications in Southern Blotting |

|---|---|---|---|

| PvuII | CAG↓CTG | 37°C | Zygosity checks for PRKN X3DEL mutation [20]. |

| EcoNI | CCTNN↓N_NNAGG | 37°C | Zygosity checks for FBXO7 FS mutation [20]. |

| NdeI | CA↓TA_TG | 37°C | Zygosity checks for DJ1 X1-5DEL mutation [20]. |

| SphI | G CATG↓C | 37°C | Detection of SYNJ1 R258Q/FS mutation [20]. |

Detailed Protocol: gDNA Digestion

This protocol is adapted from a working method for validating genome editing in human pluripotent stem cells [20].

Initial Comments: Restriction digestion must be optimized for the specific enzyme and genomic locus. The following is a general guideline.

Materials:

- Purified genomic DNA (gDNA)

- Appropriate Restriction Enzyme (e.g., PvuII, NdeI)

- Compatible Restriction Enzyme Buffer (e.g., rCutSmart Buffer)

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a nuclease-free microcentrifuge tube, assemble the following components on ice:

- gDNA: 10-15 µg

- Restriction Enzyme: 4 units per 1 µg of DNA (do not exceed 5 µl of enzyme volume per reaction)

- 10X Buffer: 5 µl

- Nuclease-free water: to a final volume of 50 µl

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C for 6 hours to overnight. Some enzymes may require alternative temperature settings.

- Completion: Following incubation, the digested DNA is ready for separation by gel electrophoresis. It is not necessary to inactivate the enzyme if the entire sample will be loaded onto the gel.

Core Component 2: Gel Electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis is the technique for separating DNA fragments by size, a prerequisite for their analysis via Southern blotting [21] [22]. The principle involves applying an electric field to force negatively charged DNA molecules through a porous agarose gel matrix; smaller fragments migrate faster and farther than larger ones, resulting in distinct bands [21] [23].

Key Principles

The electrophoretic mobility of a DNA molecule is governed by its net charge, size, and the properties of the gel matrix [21]. For nucleic acids, the phosphate backbone confers a uniform negative charge, so separation occurs primarily based on fragment size [21]. The concentration of agarose determines the effective size range of separation; lower percentages (e.g., 0.8%) are better for resolving larger fragments typical of genomic Southern blots, while higher percentages resolve smaller fragments [22] [20].

Quantitative Data on Gel Electrophoresis

Table 2: Agarose Gel Specifications for Genomic DNA Separation

| Parameter | Specification/Range | Purpose/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose Concentration | 0.8% | Optimal for separating large DNA fragments (1-20+ kb) from genomic digests [20]. |

| Gel Buffer | TAE (Tris-Acetate-EDTA) or TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA) | Maintains stable pH and provides ions for electrical conductivity [21] [22]. |

| DNA Stain | Ethidium Bromide or SYBR Safe | Intercalates into DNA for visualization under UV light [22] [20]. |

| Voltage & Runtime | Low voltage, extended time (e.g., ~20 hours) | Ensures clear separation of large DNA fragments and prevents smearing [20]. |

| Molecular Weight Marker | 1 kb DNA ladder | Serves as a reference for estimating the size of unknown DNA fragments [20]. |

Detailed Protocol: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis and DNA Denaturation

This protocol follows genomic DNA digestion and precedes capillary transfer [20].

Materials:

- Agarose powder

- Electrophoresis buffer (TAE or TBE)

- DNA staining solution

- 1 kb DNA ladder

- Gel casting tray, comb, and electrophoresis tank

- Power supply

- Denaturation buffer: 0.5M NaOH, 1.5M NaCl [20]

Procedure:

- Gel Preparation: Dissolve 0.8 g of agarose in 100 ml of electrophoresis buffer. Heat until completely dissolved, allow to cool slightly, add DNA stain, then pour into a casting tray with a well-forming comb. Allow to solidify completely [20].

- Sample Loading: Mix the digested DNA samples with a loading dye containing glycerol and a tracking dye. Pipette the samples and a 1 kb ladder into the wells.

- Electrophoresis Run: Submerge the gel in the electrophoresis tank filled with buffer. Apply a low voltage (e.g., 30-40V) and run for an appropriate duration (e.g., ~20 hours) to achieve sufficient separation [20].

- DNA Denaturation: Following electrophoresis, soak the gel in denaturation buffer (0.5M NaOH, 1.5M NaCl) to convert the double-stranded DNA into single-stranded DNA, a necessary step for subsequent hybridization with the probe [17].

Core Component 3: Capillary Transfer

Capillary transfer is the classical method for efficiently and passively moving size-separated DNA fragments from the agarose gel onto a solid nylon or nitrocellulose membrane, where they become immobilized for probing [24] [17]. This process preserves the spatial distribution of DNA bands achieved through electrophoresis.

Key Principles

The transfer relies on capillary action, where a buffer drawn upward through the gel by a stack of dry absorbent paper towels passes through the membrane, carrying the denatured DNA fragments with it. The fragments bind to the membrane upon contact, creating a replica of the gel's band pattern [17]. Nylon membranes are often preferred for their higher binding capacity (∼500 µg/cm) and durability compared to nitrocellulose [17].

Detailed Protocol: Capillary Transfer of DNA

This protocol begins after the gel has been denatured and neutralized [17] [20].

Materials:

- Glass or plastic dish

- Support platform (e.g., a glass plate)

- Whatman filter paper (3MM)

- Nylon membrane (e.g., Amersham Hybond XL)

- Absorbent paper towels or blotting paper

- Weight

- 20X SSC buffer: 3M NaCl, 0.3M sodium citrate [20]

Procedure:

- Setup the Transfer Stack: In a dish, create a platform and cover it with a wick made of Whatman paper saturated with 20X SSC buffer. The wick should be long enough to dip into the reservoir of buffer at the bottom of the dish.

- Place the Gel: Place the denatured agarose gel on top of the wick, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped between them.

- Place the Membrane: Carefully place the pre-cut nylon membrane on top of the gel. Mark the orientation and wells with a pencil. Again, exclude all air bubbles.

- Complete the Stack: Place several sheets of Whatman paper pre-wet with 20X SSC on the membrane, followed by a stack of dry paper towels (5-10 cm high). Place a glass plate on top and add a weight (∼500 g) to ensure even contact.

- Transfer: Allow the capillary transfer to proceed for 6-18 hours (overnight), ensuring the wick remains wet.

- Cross-link DNA: After transfer, carefully disassemble the stack. Cross-link the DNA to the membrane using UV light or, for nitrocellulose, bake at 80°C for 2 hours [17] [20]. The membrane is now ready for pre-hybridization and probing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the key reagents and materials required to execute the Southern blotting protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Southern Blotting

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | Site-specific digestion of genomic DNA. | PvuII, NdeI, SphI [20]. |

| Agarose | Matrix for separating DNA fragments by size via gel electrophoresis. | Standard Low EEO Agarose [20]. |

| Nylon Membrane | Solid support for immobilizing denatured DNA after transfer for probing. | Amersham Hybond XL [20]. |

| DNA Molecular Weight Marker | Reference standard for estimating the size of unknown DNA fragments on the gel. | 1 kb DNA Ladder (NEB N3232) [20]. |

| 20X SSC Buffer | High-salt buffer used during capillary transfer of DNA. | 3M NaCl, 0.3M Sodium Citrate [20]. |

| Church Buffer | Hybridization buffer for incubating the membrane with the labeled probe. | Contains 0.5M NaPO4, 7% SDS, 1% BSA [20]. |

| Radiolabeled Nucleotide ([α-³²P]-dCTP) | Radioactive label incorporated into DNA probes for high-sensitivity detection. | dCTP, [α-³²P] [20]. |

| Imaging System | Detection and documentation of signal from labeled probes on the membrane. | Azure Sapphire FL Biomolecular Imager [18]. |

The three core components integrate sequentially to enable the detection of specific DNA sequences. The process begins with restriction enzyme digestion of DNA, followed by size separation via gel electrophoresis, and culminates in the immobilization of fragments through capillary transfer, which prepares the membrane for hybridization with a labeled probe.

Mastering these foundational components is critical for generating robust and interpretable Southern blot data. This technique remains a powerful tool for detailed genomic analysis, particularly where PCR-based methods fall short, such as in sizing large structural variations and determining methylation status, thereby ensuring accurate validation in advanced genetic research and diagnostics.

The Critical Role of Probe Hybridization in Detecting Specific DNA Sequences

Southern blotting, a technique pioneered by Edwin Southern in 1975, remains a foundational method in molecular biology for detecting specific DNA sequences within complex samples [2] [18]. At the heart of this technique lies probe hybridization, a process that enables researchers to identify specific genes, analyze genomic structure, and validate genetic modifications with high specificity. The method combines gel electrophoresis with nucleic acid hybridization to create a powerful analytical tool that provides information about DNA identity, size, and abundance [25]. Despite the advent of PCR-based methods, Southern blotting maintains its relevance in applications requiring definitive validation of gene structure, including mutation detection, gene mapping, and confirmation of homologous recombination events in genetically engineered organisms [2] [26] [27].

The critical importance of probe hybridization extends across multiple research domains. In functional genetics, it serves as the definitive method for validating the structure of targeted alleles produced by homologous recombination [26]. In disease research, it facilitates the detection of gene rearrangements, deletions, and amplifications relevant to cancer studies and heritable disorders [2] [18]. For forensic applications and diagnostic testing, Southern blotting provides reliable DNA fingerprinting and mutation detection capabilities [27]. The technique's ability to deliver quantitative results reflecting the amounts of digested and undigested DNA molecules further enhances its utility in rigorous scientific applications [18].

Fundamental Principles of Southern Blot Hybridization

Molecular Basis of Specific Hybridization

The specificity of Southern blotting hinges on the complementary base pairing between the probe and target DNA sequences. Under appropriate conditions, single-stranded probe molecules form stable hydrogen bonds with their complementary sequences on the membrane-bound DNA [2]. This molecular recognition process is remarkably precise, allowing researchers to distinguish between sequences with high similarity. The stringency of hybridization—controlled by factors such as temperature, ionic strength, and solvent composition—determines the degree of sequence matching required for stable duplex formation [25]. High-stringency conditions demand perfect or near-perfect complementarity, while lower stringency permits hybridization between similar but not identical sequences, which is useful for detecting homologous genes across species [2].

The hybridization process follows predictable kinetics and thermodynamics influenced by multiple factors. Probe length significantly impacts hybridization efficiency, with longer probes (typically 500-1000 bp) providing stronger signals but potentially reduced specificity compared to shorter probes [27]. The GC content of both probe and target affects duplex stability due to the triple hydrogen bonds between guanine and cytosine versus the double bonds between adenine and thymine. Additionally, probe concentration and hybridization duration must be optimized to ensure sufficient signal intensity without excessive background [28] [20].

Critical Experimental Parameters

Several technical parameters must be carefully controlled to ensure successful hybridization outcomes. Temperature is perhaps the most critical factor, with most DNA-DNA hybridizations performed at 65°C or higher to promote specificity [28] [20]. The hybridization solution composition plays a vital role in facilitating probe-target interactions while minimizing non-specific binding. Commercial hybridization buffers like ULTRAhyb can increase sensitivity up to 100-fold compared to standard solutions by pushing hybridization to completion without increasing background [25]. Time represents another crucial parameter, with hybridization typically requiring several hours to overnight incubation to reach completion, though specialized buffers can reduce this to approximately two hours for many targets [25].

Post-hybridization washing conditions are equally important for achieving specific detection. Initial low-stringency washes with solutions such as 2X SSC remove hybridization solution and unhybridized probe, while subsequent high-stringency washes with 0.1X SSC or SSPE remove partially hybridized probe molecules [25]. The result is that only fully hybridized labeled probe molecules with complementary sequence to the region of interest remain bound to the membrane [25]. This stepwise reduction in ionic strength and potential increase in temperature effectively discriminates between perfectly matched and mismatched duplexes, ensuring that detected signals derive specifically from the target sequence.

Probe Design and Preparation Methodologies

Strategic Probe Design Considerations

Effective probe design is paramount for successful Southern blot hybridization. The fundamental requirement is that the probe sequence must be unique within the genome for the gene or locus of interest to prevent cross-hybridization with other endogenous DNA sequences [27]. Bioinformatic tools have been developed to automate this process, generating candidate probes and evaluating their potential for cross-hybridization through genome-wide similarity searches [27]. These tools employ a brute-force strategy of generating many candidate probes of acceptable length in a user-specified design window, searching all against the target genome, then scoring and ranking the candidates by uniqueness and repetitive DNA element content [27].

Several specific criteria must be considered during probe design. Probe length significantly impacts performance, with fragments of at least 300 bp required for efficient labeling in random priming reactions, though 500-1000 bp probes are typically employed in practice [27]. Repetitive elements within candidate probe sequences must be minimized or eliminated, as these can result in intense background smears upon hybridization that obscure single-copy gene hybridization signals [27]. The genomic context of the target sequence influences probe selection, with external probes (corresponding to genomic sequences adjacent to homology arms but not contained in targeting constructs) used to validate homologous recombination events, while internal probes (within the targeting construct) can serve as universal reagents for assessing allelic integrity [26].

Probe Labeling Techniques

Various labeling methods enable detection of hybridized probes, each with distinct advantages and applications. Radioactive labeling using [α-32P] dCTP provides high sensitivity and remains widely used, particularly for detecting low-abundance targets [28] [20]. However, safety concerns and regulatory restrictions associated with radioactive materials have driven the development of robust non-radioactive alternatives [26]. These include digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes detected by enzyme-linked immunoassays, biotinylated probes detected with streptavidin-enzyme conjugates, and directly fluorophore-labeled probes for immediate detection without secondary reagents [26] [18].

The selection of appropriate labeling methodology depends on multiple factors. Sensitivity requirements dictate choice, with radioactive and chemiluminescent detection generally offering the highest sensitivity. Experimental timeframe influences selection, as non-radioactive methods typically provide more rapid results without extended exposure times. Equipment availability may determine feasibility, as fluorescent detection requires appropriate imaging systems. Probe stability considerations favor non-radioactive methods, which avoid isotope decay issues. Recent advances in fluorescent detection methods, particularly near-infrared (NIR) fluorophores, offer sensitivity approaching radioactive methods with the convenience of stable reagents and direct imaging capabilities [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Southern Blot Probe Labeling and Detection Methods

| Label Type | Detection Method | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioactive ([α-32P] dCTP) | X-ray film or phosphorimaging [28] [20] | High | Maximum sensitivity; well-established protocols | Safety concerns; short probe half-life; regulatory requirements |

| Digoxigenin (DIG) | Enzyme-conjugated anti-DIG antibody + chemiluminescent substrate [26] [18] | High | Stable probes; safe handling; cost-effective | Requires optimization; multiple steps |

| Biotin | Enzyme-conjugated streptavidin + chemiluminescent substrate [18] | High | Stable probes; versatile detection | Endogenous biotin may cause background |

| Fluorescent dyes | Direct imaging with laser scanner [18] | Moderate | Rapid detection; no additional reagents | Requires specialized imaging equipment |

Experimental Protocols for Probe Hybridization

Standardized Southern Blot Protocol

The following protocol outlines a robust approach for Southern blot hybridization, adaptable for both radioactive and non-radioactive detection methods [20] [26]:

A. DNA Digestion and Electrophoresis

- Digest genomic DNA (10-15 μg) with appropriate restriction enzyme (4 U per 1 μg DNA) in recommended buffer at 37°C for 6 hours to overnight [20].

- Separate digested DNA fragments by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis at low voltage to ensure proper resolution [20].

- Include appropriate DNA size markers (e.g., 1 kb ladder) for subsequent fragment size determination [20].

B. Membrane Transfer

- Depurinate DNA in gel by incubation in 0.25M HCl for 15 minutes [20].

- Denature DNA by incubating gel in denaturation buffer (0.5M NaOH, 1.5M NaCl) for 30 minutes [20].

- Transfer DNA to positively charged nylon membrane using capillary or electrophoretic transfer methods [25].

- Immobilize DNA on membrane by UV cross-linking or baking [28].

C. Probe Preparation

- Generate probe by PCR amplification using AccuPrime Taq DNA Polymerase or similar high-fidelity enzyme [20].

- Purify PCR product using gel extraction kit to ensure probe specificity [20].

- Label probe using random primer labeling method with [α-32P] dCTP for radioactive detection or DIG/biotin labeling kits for non-radioactive detection [28] [26].

- Purify labeled probe using illustra ProbeQuant G-50 Micro Columns or similar to remove unincorporated nucleotides [20].

D. Hybridization and Detection

- Prehybridize membrane with Church buffer (1 mM EDTA, 0.5M NaPO4 pH 7.2, 7% SDS, 1% BSA) or commercial hybridization buffer (e.g., ULTRAhyb) at 65°C for 30 minutes [20] [25].

- Add labeled probe to hybridization solution at appropriate concentration (e.g., 25 ng/mL for DIG-labeled probes) and incubate at 65°C for 2 hours to overnight [28] [20] [25].

- Perform post-hybridization washes: initial wash with 2X SSC, 0.1% SDS followed by stringent wash with 0.5X SSC, 0.1% SDS at 65°C for 15 minutes each [28] [25].

- Detect hybridized probe using appropriate method: X-ray film or phosphorimager for radioactive probes, chemiluminescent substrate with X-ray film for enzyme-based detection, or direct scanning for fluorescent probes [20] [25] [18].

Critical Control Experiments

Proper experimental design includes control reactions to validate hybridization specificity and assay performance. Positive controls consisting of known restriction fragments containing the target sequence confirm probe functionality and hybridization efficiency. Negative controls with DNA samples lacking the target sequence (e.g., wild-type genomic DNA when detecting a specific mutation) verify probe specificity and identify potential cross-hybridization. Restriction digestion controls assess completion of DNA digestion, which is critical for accurate fragment size determination and interpretation [2].

For quantitative applications, standard curves generated from serial dilutions of target DNA enable quantification of target abundance in test samples. When analyzing genetically modified cells or tissues, germline controls (unmodified counterparts) provide reference bands for distinguishing between wild-type and modified alleles [2] [26]. In gene targeting experiments, both external probes (homologous to sequences outside the targeting construct) and internal probes (homologous to sequences within the targeting construct) provide complementary information about targeted integration and allele structure [26].

Diagram 1: Southern Blot Workflow with Highlighted Hybridization Steps. The critical hybridization phase encompasses membrane blocking, probe hybridization, stringent washing, and signal detection stages.

Research Reagent Solutions for Hybridization Experiments

Successful Southern blot hybridization requires specific reagents optimized for each procedural step. The following table details essential materials and their functions in hybridization experiments:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Southern Blot Hybridization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Hybridization | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, PvuII, NdeI, AseI [20] | Generate specific DNA fragments for analysis | Selection depends on restriction map of target locus; 4 U/μg DNA recommended [20] |

| Membrane Systems | Hybond-N+, Amersham Hybond XL, BrightStar-Plus [28] [20] [25] | Immobilize target DNA for hybridization | Positively charged nylon membranes preferred for DNA binding capacity [25] |

| Hybridization Buffers | Church buffer, DIG Easy Hyb, ULTRAhyb [28] [20] [25] | Create environment promoting specific probe binding | ULTRAhyb can increase sensitivity 100-fold vs. standard buffers [25] |

| Labeling Systems | [α-32P] dCTP, Prime-It II Random Primer Labeling, PCR DIG Probe Synthesis [28] [20] | Incorporate detectable tags into hybridization probes | Random primer labeling efficient for probes >300 bp [27] |

| Detection Reagents | CDP-Star, BrightStar BioDetect, radiographic film [20] [25] | Visualize hybridized probes | Chemiluminescent substrates enable non-radioactive detection with high sensitivity [25] |

Applications in Genetic Research and Validation

Gene Targeting and Validation

Southern blotting with specific probe hybridization serves as the definitive method for validating targeted genetic modifications in embryonic stem cells and genetically engineered organisms [26] [27]. This application is particularly crucial for functional genetics studies, where precise allele structure must be confirmed before phenotypic analysis. When characterizing gene-targeted events, Southern blotting reveals both the presence of the targeted allele and the number of integrations of the targeting construct into the genome [26]. The technique can distinguish between homologous recombination events (which produce a single novel band of expected size in addition to the wild-type band) and random integration events (which typically generate multiple novel bands of varying sizes) [26].

In the context of large-scale genetic engineering projects such as the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC), Southern blotting with universal probes targeting common elements in targeting constructs (e.g., lacZ or neo selectable marker sequences) has enabled high-throughput validation of targeted alleles across multiple genomic loci [26]. This approach significantly streamlines the validation process by eliminating the need for locus-specific probe design and optimization for each target gene. The reliability of Southern blotting for detecting homologous recombination events makes it indispensable for gene knockout validation, conditional allele verification, and confirmation of transgene integration patterns [27].

Mutation Detection and Genomic Rearrangements

Probe hybridization in Southern blotting enables sensitive detection of structural variations in genomic DNA, including large deletions, duplications, rearrangements, and translocations [2] [18]. In diagnostic applications, this capability permits identification of disease-associated mutations that alter restriction fragment patterns. For example, in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH), Southern blotting detects CYP21A2 gene deletions present in 25-30% of patients, which is crucial for accurate molecular diagnosis [2]. Similarly, in cancer research, Southern blotting identifies oncogene rearrangements and translocations, such as BCR/ABL translocations in hematological malignancies, providing important diagnostic and prognostic information [2].

The technique's ability to provide quantitative information about gene copy number makes it valuable for identifying gene amplifications associated with certain cancers and drug resistance mechanisms [18]. Unlike PCR-based methods, Southern blotting can detect rearrangements regardless of the specific breakpoint location within a large genomic region, making it particularly useful for analyzing genes with distributed breakpoints [2]. However, a significant limitation is that Southern blotting generally requires a relatively high proportion (5-10%) of mutant cells in the analyzed sample, making it less sensitive than some PCR-based methods for detecting minimal residual disease [2].

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

Addressing Common Hybridization Challenges

Several technical issues can compromise Southern blot hybridization results, each with specific diagnostic features and corrective approaches:

High Background Signal typically results from incomplete blocking, insufficient washing, or probe overlabeling. Remedial actions include increasing the stringency of post-hybridization washes (e.g., using 0.1X SSC with 0.1% SDS at 65°C), optimizing blocking conditions with fresh BSA (1% in Church buffer), or repurifying the labeled probe to remove unincorporated nucleotides [20] [25]. Weak or Absent Signal may indicate poor probe labeling, insufficient target DNA, or excessive stringency. Solutions include verifying probe labeling efficiency, increasing the amount of target DNA (up to 15-20 μg per lane), reducing hybridization stringency (e.g., lowering temperature to 60°C), or extending hybridization time to overnight [20] [25].

Non-specific Bands suggest cross-hybridization to related sequences or partial probe complementarity. This can be addressed by increasing hybridization stringency, using more specific probe sequences verified by bioinformatic analysis, or employing cross-species hybridization under reduced stringency conditions when studying homologous genes [2] [27]. Uneven Background often indicates improper membrane handling or uneven hybridization. Prevention methods include ensuring consistent membrane wetting before hybridization, using sufficient hybridization volume with continuous agitation, and avoiding membrane drying during processing [25].

Quantitative Optimization Approaches

Systematic optimization of key parameters significantly enhances hybridization performance:

Probe Concentration Optimization involves testing a range from 10-50 ng/mL for non-radioactive probes or 1-10 × 10^6 cpm/mL for radioactive probes to identify the concentration providing optimal signal-to-noise ratio [20] [25]. Hybridization Time Optimization balances signal intensity with practicality, with minimum times of 2 hours using specialized buffers like ULTRAhyb and maximum benefit reached by 16-18 hours for standard buffers [28] [25].

Temperature Optimization considers both hybridization and washing steps. Standard DNA-DNA hybridizations perform well at 65°C, but adjustment may be necessary for targets with atypical GC content. Similarly, wash temperature significantly impacts stringency, with increases of 5-10°C dramatically enhancing specificity for high-GC targets [28] [25]. Membrane Selection influences sensitivity and background, with positively charged nylon membranes generally preferred over nitrocellulose for their superior DNA binding capacity and mechanical strength [25].

Probe hybridization represents the definitive specificity-determining step in Southern blot analysis, enabling researchers to detect specific DNA sequences within complex genomic backgrounds. The continued relevance of this decades-old technique stems from its unique ability to provide comprehensive information about DNA identity, size, and abundance in a single assay [25] [18]. While PCR-based methods have replaced Southern blotting for some applications, the technique maintains its position as the gold standard for validating gene targeting events, detecting genomic rearrangements, and analyzing complex genetic loci [2] [26] [27].

Future directions in Southern blot hybridization include increased automation of both probe design and detection phases, enhanced sensitivity through improved labeling and detection chemistries, and integration with complementary molecular analysis techniques [18] [27]. The development of bioinformatic tools for automated probe design has already significantly reduced the time and expertise required to develop effective hybridization probes [27]. Similarly, advances in non-radioactive detection methods have addressed safety concerns while maintaining the sensitivity required for demanding applications [26] [18]. These ongoing refinements ensure that Southern blotting with specific probe hybridization will remain an essential technique in the molecular biology toolkit, providing definitive answers to critical questions about genome structure and function.

Mastering the Southern Blot Workflow: From DNA to Detection

High-Quality DNA Preparation and Restriction Enzyme Digestion

Within the framework of research aimed at detecting specific DNA sequences via Southern blotting, the initial steps of High-Quality DNA Preparation and Restriction Enzyme Digestion are critically important. The reliability and interpretability of the entire assay depend on the integrity of the genomic DNA and its complete digestion into predictable fragments [25]. This protocol details the methodologies for obtaining high-molecular-weight DNA and performing its restriction digest, forming the foundational steps for subsequent electrophoresis, transfer, and hybridization analyses [29] [15].

The process of preparing DNA for Southern blot analysis involves a sequence of key steps, from cell lysis to the final digested DNA product ready for electrophoresis.

Protocol: DNA Extraction and Purification

Cell Lysis

Initiate the protocol by lysing cells to liberate genomic DNA. For mammalian cells or tissues, use a lysis buffer containing 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.5), 5 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.2% SDS, supplemented with 100 µg/mL Proteinase K [20]. Incubate the mixture for several hours to overnight at 37°C to ensure complete digestion of cellular proteins and nucleases [20].

DNA Precipitation and Purification

Following lysis, precipitate the DNA by adding an equal volume of isopropanol and mixing vigorously until a white, filamentous DNA pellet is visible [20]. Centrifuge the sample at maximum speed (≥13,000 x g) for 5 minutes at room temperature to pellet the DNA [20]. Decant the supernatant and wash the pellet with 1 mL of 70% ethanol to remove residual salts, followed by another centrifugation step [20]. Carefully aspirate the ethanol and allow the pellet to air-dry for 10-20 minutes until it becomes translucent, ensuring it is not overdried as this hinders resuspension [20].

DNA Resuspension and Storage

Resuspend the purified DNA pellet in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and allow it to solubilize completely over 12-24 hours at 56°C [20]. Store the high-quality DNA at 4°C for immediate use or at -20°C for long-term storage.

Protocol: Restriction Enzyme Digestion

Restriction Enzyme Selection

The choice of restriction enzyme is determined by the specific experimental goal. For standard fragment analysis, frequently used enzymes include EcoRI, HindIII, and BamHI [25]. For specialized applications like methylation studies, methylation-sensitive enzymes (e.g., HpaII) are required [3]. The probe and target sequence determine the optimal enzyme choice [20].

Digestion Reaction Setup

A standard digestion reaction is assembled on ice as detailed in Table 1. Using a 4-unit excess of enzyme per µg of DNA is recommended for complete genomic DNA digestion, which is crucial for detecting single-copy genes [29] [15].

Table 1: Restriction Digestion Reaction Setup

| Component | Volume | Final Amount/Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA | Variable | 10-15 µg |

| 10X Restriction Enzyme Buffer | 5 µL | 1X |

| Restriction Enzyme | 4 U/µg DNA (max 5 µL) | 16-60 U |

| Nuclease-free Water | To 50 µL | - |

Incubation and Completion

Incubate the reaction mixture at the enzyme's optimal temperature, typically 37°C, for 6 hours to overnight [20]. Extended incubation with an enzyme excess ensures complete digestion, especially for complex genomic DNA [29]. After digestion, the DNA can be used directly for electrophoresis or concentrated by ethanol precipitation if necessary [29].

Quantitative Data and Quality Control

Successful Southern blotting requires careful quantification and quality control at each step. Key parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters for DNA Preparation and Digestion

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Quality Control Method |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Purity (A260/A280 ratio) | 1.8 - 2.0 [20] | Spectrophotometry |

| DNA Concentration | 10-15 µg per digestion [20] | Spectrophotometry or Fluorometry |

| DNA Integrity | High molecular weight (>20 kb) | Agarose Gel Electrophoresis |

| Enzyme-to-DNA Ratio | 4 U/µg DNA [20] | Calculation |

| Digestion Incubation Time | 6 hours to overnight [20] | - |

| Digestion Temperature | 37°C (for most enzymes) [20] | - |

| Complete Digestion Indicator | Smear of fragments on gel [15] | Agarose Gel Electrophoresis |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential reagents and their specific functions in the DNA preparation and digestion workflow are cataloged in Table 3.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer | Disrupts cell membranes and inactivates nucleases. | Tris-Cl, EDTA, NaCl, SDS [20] |

| Proteinase K | Digests proteins and degrades nucleases. | Added fresh to lysis buffer [20] |

| Restriction Enzymes | Sequence-specific endonucleases that cut DNA at defined sites. | EcoRI, HindIII, PvuII [20] [25] |

| Restriction Buffer | Provides optimal salt and pH conditions for enzyme activity. | rCutSmart Buffer [20] |

| TE Buffer | Stable, neutral pH buffer for DNA resuspension and storage. | 10 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA [20] |

| UltraPure Agarose | Matrix for separating DNA fragments by size via electrophoresis. | - |

Within the Southern blotting workflow, agarose gel electrophoresis is a critical separation step that occurs after DNA digestion with restriction enzymes and before membrane transfer [3] [25]. This procedure resolves the complex mixture of DNA fragments by size, forming the foundation for subsequent hybridization and detection of specific sequences. The goal of this step is to produce a gel with sharp, well-resolved DNA bands that accurately reflect the fragment sizes present in the sample, enabling reliable analysis in diagnostic and research applications, such as detecting large tandem repeat expansions in genetic disorders [3].

Principle of Separation

Agarose gel electrophoresis separates DNA fragments based on their size by applying an electric field to a gel matrix. DNA molecules, being negatively charged due to their phosphate backbone, migrate toward the positive anode [30]. The agarose gel acts as a molecular sieve; smaller fragments navigate the porous network more easily and travel faster, while larger fragments are impeded and migrate more slowly [30] [31]. The distance a DNA fragment travels is inversely proportional to the logarithm of its molecular weight [30]. For Southern blotting, this separation allows a DNA ladder of known sizes to be used as a reference for estimating the size of unknown restriction fragments in the patient's sample [3].

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for successful agarose gel electrophoresis:

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose | Forms the porous gel matrix for separation. | Standard or high-resolution grades (e.g., MetaPhor) for fragments <20 bp apart [32]. |

| Running Buffer (1X TAE or TBE) | Conducts current and maintains stable pH. | TAE is preferred for longer fragments (>1 kb) and downstream enzymatic steps; TBE offers better buffering capacity for long runs and resolution of smaller fragments [33] [31]. |

| DNA Ladder | Provides molecular weight standards for sizing unknown fragments. | Select a ladder with bands in the expected size range; chromatography-purified ladders ensure accuracy [33]. |

| Loading Dye | Adds density for well-loading and contains tracking dyes to monitor migration. | Contains dyes like bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol; avoid dyes that comigrate with bands of interest [33] [30]. |

| Staining Agent (e.g., Ethidium Bromide) | Intercalates with DNA for visualization under UV light. | Ethidium bromide is a known mutagen; handle with care. Safer, non-carcinogenic alternatives include SYBR Safe, SYBR Gold, Crystal Violet, or Methyl Blue [30]. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Cut genomic DNA into specific fragments for analysis. | High-quality enzymes ensure complete digestion. Validation for use with universal buffers is recommended [25]. |

Equipment

- Gel casting apparatus (tray and combs)

- Horizontal gel electrophoresis chamber and power supply

- Microwave or hot plate for melting agarose

- UV transilluminator or gel documentation system

- Pipettes and tips

Protocol

Gel Preparation

- Calculate Gel Concentration: Choose an agarose percentage based on the expected size of your DNA fragments to achieve optimal separation. Refer to Table 1 for guidance.

- Dissolve Agarose: Weigh the appropriate amount of agarose and mix with the desired volume of 1X TAE or TBE buffer in a heat-resistant flask. The buffer must match the one used in the electrophoresis tank [34].

- Heat the Mixture: Heat the mixture in a microwave oven using short bursts, swirling intermittently, until the agarose is completely dissolved and the solution is clear. Avoid vigorous boiling to prevent evaporation that alters gel concentration [34] [30].

- Cool Agarose: Allow the molten agarose to cool to approximately 50-55°C to prevent warping of the casting tray [34] [35]. Swirl the flask occasionally to ensure even cooling.

- Add Stain (Optional): If incorporating stain directly into the gel, add the appropriate volume (e.g., ethidium bromide to a final concentration of 0.2-0.5 μg/mL) and mix thoroughly [34] [30]. Always wear personal protective equipment when handling mutagens.

- Cast the Gel: Place the comb in the gel tray on a level surface. Pour the cooled agarose solution into the tray, avoiding air bubbles. If bubbles form, remove them with a pipette tip. Let the gel solidify completely at room temperature for 20-30 minutes [34] [30].

Sample Preparation and Loading

- Prepare DNA Samples: Mix DNA samples with a loading dye containing glycerol or Ficoll. A typical ratio is 5 μL of loading dye per 25 μL of DNA sample [34]. For Southern blotting, the DNA is already digested with restriction enzymes in the previous step [3] [25].

- Prepare DNA Ladder: Dilute the DNA ladder as recommended by the manufacturer and mix it with the same loading dye.

- Set Up Gel Box: Once solidified, carefully remove the comb and place the gel in the electrophoresis chamber. Submerge the gel completely with 1X running buffer, ensuring the gel is covered by about 3-5 mm of buffer [33] [34].

- Load Samples: Using a pipette, slowly load the prepared DNA ladder and samples into the wells. Maintain positive pressure to prevent buffer from entering the pipette tip and load steadily to ensure the sample sinks to the bottom of the well [34].

Electrophoresis Conditions

- Connect Power Supply: Ensure the electrodes are correctly connected—the DNA, being negatively charged, will migrate toward the positive anode (red). "Always Run to Red" [34].

- Set Voltage and Run: Apply a voltage of 1-5 V per cm of gel length [30]. For a standard mini-gel, 80-150 V is common. Run the gel until the dye front has migrated 75-80% of the way down the gel [34]. Lower voltages run for longer times often improve band resolution.

- Post-Run Visualization: After turning off the power, carefully remove the gel. If the stain was not added during gel preparation, perform post-staining by soaking the gel in a staining solution (e.g., EtBr in TAE buffer) for 15-30 minutes, followed by a destaining step in water if necessary [34] [30]. Visualize the DNA bands using a UV transilluminator or blue light system.

Expected Results and Analysis

A successful electrophoresis run will display sharp, well-defined DNA bands. The DNA ladder will show a series of distinct bands corresponding to known fragment sizes, against which the sizes of the sample fragments can be estimated [3] [30]. In Southern blotting for conditions like myotonic dystrophy, the size of the fragments is critical, as the severity of the phenotype can depend on the size of a repeat expansion [3]. The separated DNA fragments are now ready for the subsequent transfer step in the Southern blotting workflow.

Agarose Concentration Guidelines

Table 1: Guidelines for agarose gel concentration based on DNA fragment size. Adapted from [32].

| Target DNA Size Range | Recommended Agarose Concentration |

|---|---|

| 500 bp - 25 kb | 0.7% - 1.0% |

| 750 bp - 2,000 bp | 1.3% |

| 500 bp - 750 bp | 1.7% - 2.0% |

| 250 bp - 500 bp | 2.5% - 3.0% |

| < 250 bp | 3.0% - 4.0% |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 2: Common issues, their causes, and solutions in agarose gel electrophoresis.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Faint or No Bands | Insufficient DNA loaded, sample degradation, incorrect electrode connection, or stain sensitivity [36]. | Load 0.1-0.2 μg of DNA per mm of well width; ensure reagents are nuclease-free; check that the negative electrode (black) is at the well end; use fresh stain or increase staining time [36]. |

| Smeared Bands | Sample overloaded, DNA degradation, gel too thick (>5 mm), or voltage too high [36]. | Reduce the amount of DNA loaded; practice good aseptic technique to avoid nucleases; cast gels 3-4 mm thick; run the gel at a lower voltage [36]. |

| Poor Band Resolution | Incorrect agarose percentage, voltage too high, or poorly formed wells [36] [34]. | Use a higher percentage agarose for smaller fragments; lower the voltage for longer run times; ensure the comb is clean and not pushed to the very bottom of the tray [36]. |

| "Smiling" Effect (bands curve upward) | Uneven heating across the gel, typically from excessively high voltage [33]. | Reduce the voltage during the run and ensure the electrophoresis tank is functioning properly with good contact [33]. |

Workflow Integration

The following diagram illustrates the position of gel electrophoresis within the complete Southern blot analysis workflow.

Following DNA digestion and gel electrophoresis, the efficient transfer of separated DNA fragments from the gel to a solid membrane is a critical step in Southern blotting. This process creates a permanent replica of the fragment pattern for subsequent hybridization and analysis. The two principal methods for this transfer are capillary and vacuum blotting. This application note details the protocols for both, providing researchers with the information needed to achieve consistent, high-quality results.

Principles of Membrane Transfer

After electrophoresis, DNA fragments are immobilized within the gel matrix, making them inaccessible for hybridization with labeled probes. Transfer moves these fragments onto a thin, porous membrane, which provides a durable and accessible support. The DNA is typically denatured into single strands before or during transfer to facilitate later binding to the probe [17].

The choice of membrane is crucial. While nitrocellulose was used traditionally, positively charged nylon membranes are now widely preferred due to their higher tensile strength and greater DNA binding capacity, approximately 500 µg/cm compared to nitrocellulose's 100 µg/cm [17]. These membranes are ideal for use with both radioactive and non-isotopic probes to achieve a strong hybridization signal with minimal background [25].

Comparative Analysis of Transfer Methods

The two most common transfer techniques are capillary action and vacuum blotting. The table below summarizes their key characteristics for easy comparison.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Capillary and Vacuum Blotting Methods

| Characteristic | Capillary (Upward) Blotting | Vacuum Blotting |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Passive transfer via capillary action, drawing buffer upward through the gel and membrane into a stack of dry absorbent paper [17]. | Active transfer where a vacuum sucks buffer downward through the gel and membrane into an absorbent material [37] [38]. |

| Typical Duration | Several hours to overnight [17] [25]. | About 1 hour [17]. |

| Simplicity & Cost | Simple setup, requires no special equipment other than a stack of paper towels and a weight. | Requires a vacuum blotting apparatus and a regulated vacuum source [17]. |

| Efficiency & Consistency | Reliable but slow; efficiency can be lower for larger fragments (>15 kb) without a depurination step [17]. | Faster and more consistent transfer; efficient for a range of fragment sizes [39]. |

| Risk of Gel Collapse | Low risk. | Moderate risk; a strong vacuum can collapse the gel, blocking transfer [37]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Capillary Transfer

This traditional method is valued for its simplicity and minimal equipment requirements.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- Membrane: Positively charged nylon membrane (e.g., Invitrogen BrightStar-Plus) [25].

- Transfer Buffer: High-salt buffer, typically 20X SSC (3 M Sodium Chloride, 0.3 M Sodium Citrate) [17].

- Absorbent Stack: A stack of paper towels or other dry absorbent papers.

- Whatman 3MM Paper: For creating the wick and the gel/membrane sandwich.

- Weight: A lightweight object (approx. 200 g) to place on top of the stack.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Post-Electrophoresis Treatment:

- Depurination (Optional): For DNA fragments larger than 15 kb, soak the gel in 0.25 M HCl for 15-30 minutes with gentle agitation. This acid depurination step cleaves the DNA into smaller, more easily transferable fragments. Rinse the gel thoroughly with deionized water after this step [17].

- Denaturation: Submerge the gel in a denaturing solution (e.g., 0.5 M NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl) for 30 minutes with gentle agitation. This converts double-stranded DNA into single strands [17].

- Neutralization: Soak the gel in a neutralizing solution (e.g., 0.5 M Tris-HCl, 3 M NaCl, pH 7.4) for 30 minutes with gentle agitation [17].

Assembly of the Transfer Stack:

- Fill a glass or plastic dish with a sufficient volume of 20X SSC transfer buffer.

- Place a platform over the buffer and lay a wick of Whatman 3MM paper over it, with both ends submerged in the buffer to draw it upward.

- Place the gel on the wick, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped between them.