siRNA for Targeted Gene Knockdown: From Design Principles to Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of small interfering RNA (siRNA) for targeted gene silencing.

siRNA for Targeted Gene Knockdown: From Design Principles to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of small interfering RNA (siRNA) for targeted gene silencing. It covers the foundational mechanism of RNA interference and explores the latest advances in siRNA design, delivery platforms, and optimization strategies to enhance efficacy and minimize off-target effects. A strong emphasis is placed on robust validation methodologies and comparative analysis of different siRNA formats. The content also discusses the translation of siRNA technology from a research tool to a growing class of therapeutics, addressing both current successes and ongoing challenges in the field.

The siRNA Revolution: Understanding the Core Mechanism and Therapeutic Potential

RNA interference (RNAi) is a highly conserved biological mechanism that facilitates post-transcriptional gene silencing across diverse eukaryotic organisms, including plants, insects, and mammals [1] [2]. This pathway utilizes small non-coding RNA molecules to direct the sequence-specific silencing of complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) targets. The most well-studied RNAi molecules are small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), which operate through related but distinct pathways to regulate gene expression [1]. Since the initial discovery of RNAi in Caenorhabditis elegans in 1998, and the subsequent awarding of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2006 to the scientists who elucidated this mechanism, RNAi technology has evolved into a powerful tool for genetic research and therapeutic development [3] [2].

Therapeutically, siRNA-based approaches have gained significant momentum following regulatory approval of the first siRNA drug, patisiran, in 2018 for the treatment of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis [3]. Since then, several additional siRNA therapeutics have received approval (givosiran, lumasiran, inclisiran, vutrisiran, and nedosiran), with over 260 siRNA drug candidates currently in preclinical or clinical development across therapeutic areas including cancer, infectious diseases, neurological conditions, cardiovascular disorders, and diabetes [3] [1]. The programmable nature of siRNA molecules, where target specificity is determined primarily by the guide strand sequence, makes them exceptionally versatile tools for selectively silencing disease-associated genes previously considered "undruggable" [4].

The Core Mechanism: From siRNA Delivery to mRNA Degradation

siRNA Structure and Cellular Uptake

Synthetic siRNAs are typically 21-25 nucleotide double-stranded RNA duplexes with 3' dinucleotide overhangs on both strands [3] [5]. The duplex consists of two complementary strands: the antisense (guide) strand, which ultimately directs target recognition, and the sense (passenger) strand, which is degraded during RISC activation [5]. For experimental applications, siRNAs are most commonly generated through solid-phase chemical synthesis methods that yield highly pure, stable oligonucleotides that can be readily chemically modified to enhance their properties [5].

A critical challenge in siRNA applications lies in achieving efficient intracellular delivery. Naked, unmodified siRNAs face substantial barriers including rapid degradation by ubiquitous ribonucleases in biological fluids, renal clearance, inefficient cellular uptake due to their negative charge, and potential immunogenicity [3] [2]. Multiple delivery strategies have been developed to overcome these limitations:

- Transfection: Cationic liposomes or polymers form complexes with negatively charged siRNA, facilitating cellular uptake through endocytosis. While effective for many cell types, not all cells are amenable to transfection reagents [5].

- Electroporation: Application of an electrical pulse creates temporary pores in the cell membrane, allowing siRNA entry. This method is effective for difficult-to-transfect cells but may increase cell death [5].

- Viral-Mediated Delivery: Engineered viral vectors (lentivirus, retrovirus, adeno-associated virus) enable efficient delivery and stable expression in difficult-to-transfect cells and in vivo applications, though they may trigger antiviral responses and require specialized facilities [5].

- Chemically Modified siRNA: Incorporation of strategic chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro groups) can enhance nuclease resistance and enable passive cellular uptake in some cases without transfection reagents [3] [5].

RISC Assembly and Activation

Once inside the cytoplasm, the siRNA duplex undergoes a carefully orchestrated process of RISC assembly and activation [6]. The double-stranded siRNA is recognized and loaded into the multi-protein RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Central to RISC function is the Argonaute 2 (AGO2) protein, an endonuclease that serves as the catalytic engine of the complex [3] [6] [7].

During RISC activation, the siRNA duplex is unwound in an ATP-independent manner, and the passenger strand is selectively ejected and degraded. The guide strand is retained by AGO2 to form the mature, single-stranded siRNA-RISC complex [3] [1]. The selection of which strand serves as the guide is influenced by the relative thermodynamic stability of the duplex ends, with the strand whose 5' end is less stably paired preferentially loaded as the guide [1]. Recent research has highlighted that the specific guide-RNA sequence can significantly impact the kinetics of RISC activation and subsequent target cleavage, with different sequences exhibiting up to 250-fold variations in slicing rates [8].

Target Recognition and mRNA Cleavage

The mature RISC complex, guided by the siRNA strand, scans cellular mRNAs for complementary sequences [6]. When the guide RNA pairs with its target mRNA through Watson-Crick base pairing, predominantly within the seed region (nucleotides 2-8), the AGO2 protein catalyzes site-specific endonucleolytic cleavage of the mRNA [3]. This cleavage occurs between nucleotides corresponding to positions 10 and 11 relative to the 5' end of the guide strand [3].

The cleaved mRNA fragments are then rapidly degraded by cytoplasmic exonucleases, effectively preventing translation and abrogating protein synthesis [3]. The RISC complex itself can subsequently engage in multiple rounds of target identification and cleavage, amplifying the gene silencing effect from a single siRNA-RISC complex [6].

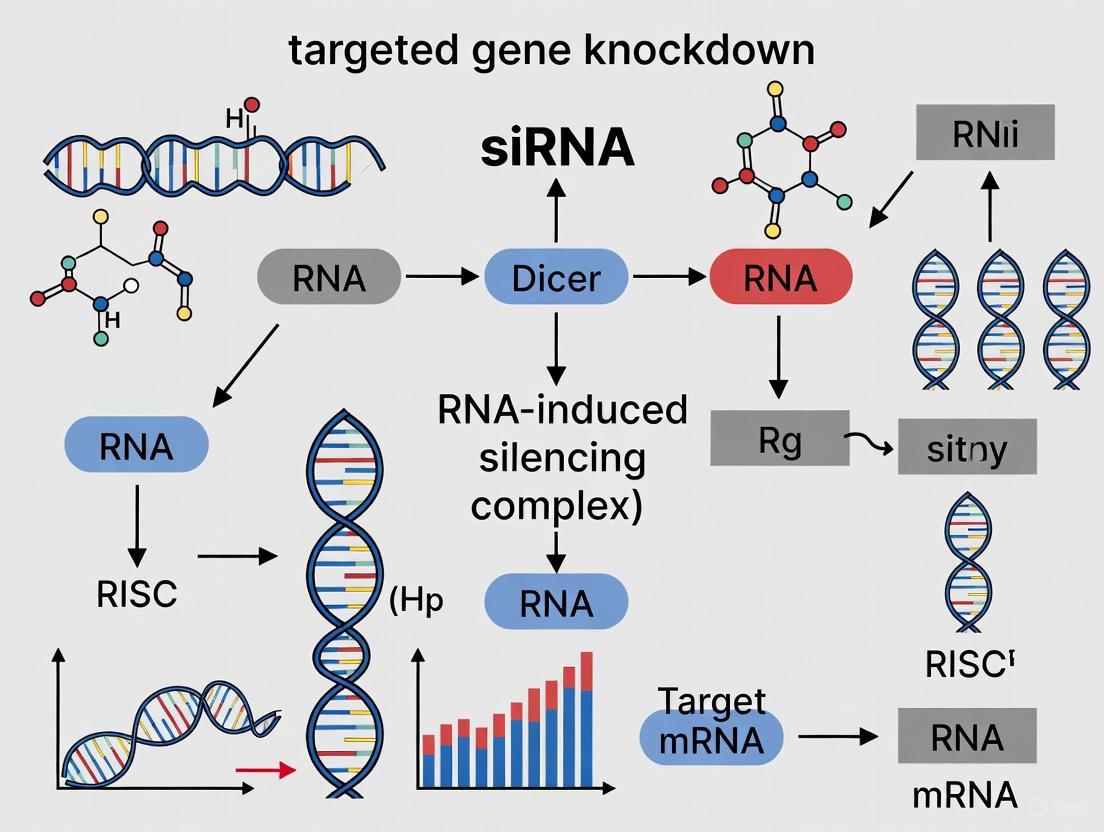

The following diagram illustrates the complete siRNA-mediated gene silencing pathway:

Quantitative Analysis of siRNA Efficacy Factors

Multiple factors influence the efficacy of siRNA-mediated gene silencing. The following table summarizes key sequence and structural features that impact silencing efficiency, based on systematic analyses:

Table 1: Key Features Impacting siRNA Efficacy and Specificity

| Feature | Impact on Efficacy | Optimal Characteristics | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guide Strand Sequence | High variation in silencing efficiency [8] | Sequences enabling faster RISC slicing kinetics [8] | Different guide sequences alter slicing rates by >250-fold; faster slicing improves knockdown [8] |

| Central Pairing Stability | Impacts 3'-mismatch tolerance [8] | Moderate stability; AU-rich centers have weak activity and require extensive 3' complementarity [8] | Guides with weak central pairing require extensive 3' complementarity to populate slicing-competent conformation [8] |

| Seed Region (nt 2-8) | Critical for target recognition; major source of off-target effects [5] | Avoid high complementarity to non-target transcripts [5] | Seed region homology can cause unintended silencing of transcripts with partial complementarity [5] |

| GC Content | Moderate impact [4] | <60% [4] | High GC content can negatively impact silencing efficiency and increase off-target effects [4] |

| Chemical Modification Pattern | Significant impact on stability and activity [4] | High 2'-O-methyl content improves nuclease resistance [4] | Modification pattern significantly impacts efficacy more than structural features; essential for in vivo stability [4] |

| Duplex Structure | Limited impact [4] | Asymmetric (3' overhangs) or blunt; sequence-dependent effects [4] | Structural features (symmetric vs. asymmetric) show minimal impact on efficacy compared to sequence and modification [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing

This protocol describes a standardized methodology for evaluating siRNA efficacy in mammalian cell cultures, incorporating design considerations, delivery optimization, and functional validation.

siRNA Design and Preparation

Target Sequence Selection:

- Identify 19-21 nucleotide target sequences within the mRNA of interest, typically within the open reading frame (ORF) or 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) [4].

- Apply design algorithms (e.g., SMARTselection) that incorporate rules for minimizing off-target effects: avoid sequences with ≥60% GC content, exclude CCCC or GGGG stretches, and avoid high-frequency seed sequences from known mammalian microRNAs [4] [5].

- BLAST potential sequences against the appropriate genome database to ensure specificity for the target gene.

- Recommendation: Design and test 3-4 individual siRNAs targeting different regions of the mRNA to identify the most effective sequence [5].

Control siRNAs:

- Positive Control: A well-characterized siRNA targeting a ubiquitously expressed gene (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) to validate delivery efficiency and silencing capability [5].

- Negative Control: A scrambled sequence siRNA with no significant homology to any known genes in the target organism, or a siRNA targeting a non-human gene (e.g., GFP) [5].

- Untreated Control: Cells receiving transfection reagent alone to establish baseline gene expression and assess potential cytotoxicity of the transfection process [5].

Cell Seeding and Transfection

Cell Preparation:

- Culture appropriate cell lines (e.g., HeLa, HEK293) under standard conditions.

- Seed cells in 24-well or 12-well plates at 30-50% confluence in antibiotic-free medium 18-24 hours before transfection to ensure active cell division at the time of transfection.

Transfection Complex Formation:

- For a single well of a 24-well plate, dilute 20-50 nM siRNA in 50 µL of serum-free Opti-MEM medium. Gently mix.

- In a separate tube, dilute 1-2 µL of a cationic lipid-based transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine RNAiMAX) in 50 µL of serum-free Opti-MEM. Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Combine the diluted siRNA with the diluted transfection reagent. Mix gently and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature to allow siRNA-lipid complex formation.

Transfection:

- Add the 100 µL siRNA-lipid complex dropwise to cells containing fresh, complete growth medium.

- Gently swirl the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Incubate cells at 37°C in a CO₂ incubator for 24-72 hours before analysis.

Functional Validation and Analysis

mRNA Knockdown Assessment (qRT-PCR):

- Timepoint: Harvest cells 48 hours post-transfection for optimal mRNA knockdown analysis.

- Procedure: Isolate total RNA using a commercial kit. Perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA. Conduct quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using primers specific for the target gene and housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) for normalization.

- Analysis: Calculate percentage knockdown using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method relative to negative control siRNA-treated cells.

Protein Knockdown Assessment (Western Blot):

- Timepoint: Harvest cells 72 hours post-transfection for optimal protein-level analysis, accounting for protein half-life.

- Procedure: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer, separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to a membrane, and probe with antibodies against the target protein and a loading control (e.g., β-tubulin, GAPDH).

- Analysis: Quantify band intensity using densitometry software and normalize to loading controls to determine percentage protein reduction.

Phenotypic Analysis (If Applicable):

- Depending on the target gene, perform functional assays (e.g., proliferation, apoptosis, migration) at relevant timepoints to correlate gene silencing with biological effects.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for siRNA Experiments

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Predesigned siRNA Libraries (e.g., siGENOME, ON-TARGETplus) [5] | Target-specific gene silencing | Expert-designed sequences; available with chemical modifications to reduce off-target effects; often available in pooled formats (SMARTpools) [5] |

| Cationic Lipid-Based Transfection Reagents [5] | Deliver siRNA into cells | Form complexes with siRNA via electrostatic interactions; suitable for many standard cell lines; optimization of lipid:siRNA ratio is critical for efficiency and minimizing cytotoxicity |

| Accell siRNA [5] | Delivery to difficult-to-transfect cells | Chemically modified for passive uptake without transfection reagents; enables gene silencing in sensitive primary cells and neurons; serum can inhibit delivery efficiency |

| Validated Positive Control siRNAs [5] | Experimental control | Target essential, ubiquitously expressed genes (e.g., GAPDH, Polo-like Kinase 1); verify transfection efficiency and silencing capability in each experiment |

| Scrambled Negative Control siRNAs [5] | Experimental control | No significant sequence identity to any known gene; distinguishes sequence-specific silencing from non-specific effects of transfection or cellular stress |

| qRT-PCR Assays | Quantify mRNA knockdown | Gene-specific primers/probes; require stable housekeeping genes for normalization; critical for validating target engagement at the mRNA level |

| Validated Antibodies | Quantify protein knockdown | Target-specific antibodies with demonstrated specificity for Western blot; required to confirm functional silencing at the protein level |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for siRNA Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Silencing Efficiency | Ineffective transfection; poor siRNA design; insufficient incubation time | Optimize transfection conditions (reagent concentration, complexation time); test alternative siRNAs targeting different regions; extend time between transfection and analysis (up to 72-96 hours) [5] |

| High Cell Toxicity | Transfection reagent cytotoxicity; excessive siRNA concentration | Titrate down transfection reagent and siRNA concentrations; try less cytotoxic delivery methods (e.g., polymer-based reagents, Accell siRNA) [5] |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Uneven cell seeding; improper transfection complex formation | Ensure homogeneous cell suspension when seeding; mix transfection complexes thoroughly before addition; add complexes dropwise across the well surface |

| Off-Target Effects | Seed region homology; passenger strand activity | Use siRNAs with validated specificity; employ pooled siRNA designs; utilize siRNAs with chemical modifications that reduce passenger strand loading and seed-mediated off-targets [5] |

| Inefficient Delivery in Difficult Cells | Low division rate; primary cells; complex morphology | Utilize specialized delivery methods (e.g., Accell siRNA, electroporation, viral delivery) optimized for challenging cell types [5] |

The discovery of RNA interference (RNAi) represents a paradigm shift in molecular biology, providing researchers with a powerful tool for targeted gene knockdown. This phenomenon, first identified in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, has evolved from a fundamental biological curiosity to a revolutionary therapeutic platform. The translation of this natural gene silencing mechanism into clinically approved medicines marks one of the most significant advancements in modern pharmacotherapy, enabling the precise targeting of previously undruggable genes [3]. This Application Note details the key historical milestones in siRNA therapeutics, providing experimental context and methodological frameworks that have facilitated this remarkable journey from basic research to clinical application, with particular emphasis on the foundational discoveries made in C. elegans.

Historical Timeline and Foundational Discovery in C. elegans

The RNAi timeline began with pivotal basic research in a model organism, which ultimately unlocked a new therapeutic modality. The following table summarizes the major historical milestones:

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in siRNA Therapeutics

| Year | Milestone | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Discovery of RNAi in C. elegans [3] | Foundational research by Fire and Mello demonstrated that double-stranded RNA could potently and specifically silence gene expression in C. elegans. |

| 2006 | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine [3] | Andrew Fire and Craig C. Mello were awarded the Nobel Prize for their discovery of RNA interference. |

| 2018 | First FDA-approved siRNA drug, Patisiran [9] [10] [11] | Patisiran (ONPATTRO) was approved for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis with polyneuropathy, validating siRNA as a human therapeutic. |

| 2019-2023 | Approval of five additional siRNA drugs [9] [10] [11] | Givosiran (2019), Lumasiran (2020), Inclisiran (2021), Vutrisiran (2022), and Nedosiran (2023) were approved, expanding the scope of treatable diseases. |

The initial discovery was made in C. elegans, a small, transparent nematode that is a premier model organism in biological research due to its simplicity, short life cycle, and completely mapped cell lineage [12] [13]. Its anatomical simplicity—about 1000 somatic cells and a fully sequenced genome—made it an ideal system for uncovering fundamental genetic mechanisms [13] [14]. This discovery illuminated a conserved gene regulatory pathway that would later be exploited for therapeutic development.

Currently Approved siRNA Therapeutics

Since the 2018 approval of Patisiran, the siRNA therapeutic landscape has expanded rapidly. All approved agents are double-stranded RNAs designed to target specific mRNA sequences in hepatocytes, facilitated by advanced delivery systems [10] [11]. The following table provides a detailed comparison of the currently approved siRNA drugs.

Table 2: FDA-Approved siRNA Therapeutics (as of 2025)

| Brand Name (Generic) | Approval Year | Indication | Molecular Target | Delivery System | Dosing Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONPATTRO (Patisiran) [9] [10] [11] | 2018 | Hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR) with polyneuropathy | Transthyretin (TTR) mRNA | Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) | IV infusion every 3 weeks |

| GIVLAARI (Givosiran) [9] [10] [11] | 2019 | Acute Hepatic Porphyria (AHP) | Aminolevulinate synthase 1 (ALAS1) mRNA | GalNAc conjugate | Subcutaneous injection monthly |

| OXLUMO (Lumasiran) [9] [10] [11] | 2020 | Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1 (PH1) | Hydroxyacid oxidase 1 (HAO1) mRNA | GalNAc conjugate | Subcutaneous injection (initial 3 monthly, then quarterly) |

| LEQVIO (Inclisiran) [9] [10] [11] | 2021 | Hypercholesterolemia | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) mRNA | GalNAc conjugate | Subcutaneous injection (at 0, 3 months, then every 6 months) |

| AMVUTTRA (Vutrisiran) [9] [10] | 2022 | hATTR with polyneuropathy | Transthyretin (TTR) mRNA | GalNAc conjugate | Subcutaneous injection every 3 months |

| RIVFLOZA (Nedosiran) [9] [10] | 2023 | Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1 (PH1) | Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) mRNA | GalNAc conjugate | Subcutaneous injection monthly |

A critical differentiator among these therapies is their delivery technology. Patisiran utilizes a lipid nanoparticle (LNP) system for encapsulation and delivery to hepatocytes. In contrast, the other five approved drugs employ N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) conjugation, which facilitates highly efficient uptake by hepatocytes through binding to the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) on the cell surface [10] [11] [3]. This targeted delivery approach minimizes systemic exposure and enhances therapeutic efficacy.

Core Mechanism of Action and Experimental Workflow

The RNAi Pathway

The therapeutic action of siRNAs harnesses the endogenous RNA interference pathway. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of siRNA-mediated gene silencing after cellular uptake.

The mechanism involves a conserved, multi-step pathway [9] [3]:

- Cytosolic Entry and RISC Loading: The synthetic siRNA duplex is introduced into the cell cytoplasm, aided by its delivery system (LNP or GalNAc). The RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), particularly the Argonaute-2 (AGO2) endonuclease, incorporates the siRNA.

- Strand Separation and Activation: The siRNA duplex is unwound, the passenger (sense) strand is ejected and degraded, and the guide (antisense) strand remains bound to RISC, forming the active complex.

- Target Recognition and Cleavage: The guide strand directs the activated RISC to its complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) target via Watson-Crick base pairing. The AGO2 enzyme within RISC catalyzes the endonucleolytic cleavage of the target mRNA.

- Gene Silencing: The cleaved mRNA fragments are rapidly degraded by cellular exonucleases, preventing translation into the target protein and effectively silencing gene expression. The activated RISC can catalyze multiple rounds of mRNA cleavage, providing sustained effect.

Protocol: In Vitro Assessment of siRNA Efficacy

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for validating siRNA efficacy and cytotoxicity in cell culture models, a critical step in therapeutic development.

Title: Basic Workflow for In Vitro siRNA Screening

Objective: To transfert siRNA into cultured cells and evaluate its target knockdown efficiency and potential cytotoxicity.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 3.

- Equipment: Cell culture hood, CO2 incubator, micropipettes, centrifuge, multi-well plates, real-time PCR system, spectrophotometer/fluorometer.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for In Vitro siRNA Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Validated siRNA | The active molecule for gene knockdown. | Include both target-specific and non-targeting negative control siRNAs. |

| Transfection Reagent | Facilitates siRNA entry into cells. | Cationic lipids or polymers (e.g., Lipofectamine RNAiMAX [15]). |

| Cell Line | Model system for testing. | Should express the target mRNA; can be a stable overexpression line [15]. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Supports cell growth and health. | Serum-free medium (e.g., Opti-MEM) is often used during transfection. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Quantifies mRNA levels post-transfection. | Probes or dyes specific for the target and housekeeping genes. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kit | Measures cytotoxicity. | MTT, MTS, or similar assays [15]. |

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells in a multi-well plate at 30-50% confluence in appropriate growth medium and allow to adhere for 24 hours [15].

- siRNA-Transfection Complex Preparation:

- Dilute the siRNA (e.g., 5-50 nM final concentration) in a serum-free medium (e.g., Opti-MEM).

- Dilute the transfection reagent separately in the same medium.

- Combine the diluted siRNA and transfection reagent, mix gently, and incubate for 15-20 minutes at room temperature to allow complex formation.

- Transfection: Add the siRNA-transfection complexes directly to the cells in a drop-wise manner. Gently swirl the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for 24-48 hours at 37°C in a CO2 incubator.

- Harvest and Analysis:

- Viability Assay: At 24 hours post-transfection, perform an MTT assay. Incubate cells with MTT reagent for several hours, then measure absorbance at 570 nm to determine cell viability relative to controls [15].

- Knockdown Efficiency: At 48 hours post-transfection, harvest cells for RNA extraction. Perform quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using primers specific to the target gene. Normalize target mRNA levels to a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) and calculate percentage knockdown relative to cells treated with a non-targeting control siRNA [15].

Key Technological Breakthroughs: Delivery and Stabilization

The clinical translation of siRNA faced significant hurdles, including rapid degradation in serum, inefficient cellular uptake, and potential immunogenicity. Key innovations overcame these barriers:

Chemical Modifications: Strategic modifications to the siRNA backbone dramatically improved stability and pharmacokinetics. Common modifications include [3]:

- Sugar Modifications: 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-fluoro (2'-F), and Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) in the ribose ring to enhance nuclease resistance and binding affinity.

- Backbone Modifications: Phosphorothioate (PS) linkages, which replace a non-bridging oxygen with sulfur, increasing stability against nucleases and promoting protein binding for improved tissue distribution.

- Terminal Modifications: Conjugation of ligands like GalNAc for targeted delivery.

Advanced Delivery Systems: Two primary delivery platforms have been successfully implemented in the clinic [10] [11] [3]:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): As used in Patisiran, LNPs protect the siRNA from degradation, facilitate endosomal escape, and are efficiently taken up by hepatocytes.

- GalNAc Conjugation: A trivalent N-acetylgalactosamine molecule conjugated to the siRNA enables high-affinity binding to the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) on hepatocytes, triggering rapid receptor-mediated internalization. This efficient targeting allows for subcutaneous administration and less frequent dosing [10].

The journey of siRNA from its serendipitous discovery in C. elegans to a robust therapeutic platform exemplifies the power of basic biological research to fuel clinical innovation. The six currently approved drugs, with their durable effects and novel targeting mechanisms, have established RNAi as a distinct and valuable drug class, particularly for rare genetic liver disorders [11]. The experimental protocols and tools outlined in this Application Note provide a framework for researchers to explore new applications.

The future of siRNA therapeutics is expansive. Ongoing research focuses on overcoming remaining challenges, such as delivery to tissues beyond the liver. Advances in novel conjugation strategies, lipid and polymer nanoparticles, and innovative chemical modifications are actively being pursued to target the central nervous system, ocular tissues, and tumors [15] [3]. Furthermore, the exploration of siRNA for highly prevalent conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, with Inclisiran as a pioneer, opens the door for a significant expansion of its impact on public health. As delivery technologies mature, the siRNA pipeline is poised to silence previously unreachable genetic drivers of disease, solidifying its role in the next generation of precision medicines.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) is a foundational tool in molecular biology for achieving targeted gene knockdown via the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. This application note details the core structural components of siRNA—the guide and passenger strands—and elucidates the critical role of the Dicer enzyme in their biogenesis and function. Framed within the context of gene knockdown research, this document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with structured data, experimental protocols, and key resource information to support the design and implementation of effective siRNA-based experiments.

Core Components of siRNA

Structural Anatomy of siRNA

siRNA is a synthetic RNA duplex typically 21–23 nucleotides (nt) in length, designed to specifically target a particular mRNA for degradation [5]. Its canonical structure consists of several key features:

- Double-Stranded Duplex: Two RNA strands form a duplex 19 to 25 base pairs (bp) in length [5] [16].

- 3' Overhangs: The duplex often features 2-nt 3' overhangs on both ends, a characteristic inherited from its processing by Dicer [16].

- Strand Asymmetry: The two strands are functionally distinct:

- Guide Strand (Antisense Strand): This strand is selectively loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and serves as the sequence-specific guide for identifying complementary mRNA targets [5].

- Passenger Strand (Sense Strand): This strand is displaced and degraded during RISC activation [17].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Canonical siRNA

| Feature | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 21–23 nt duplex; 19–25 bp | Optimal for RISC loading and function [5] [16] |

| Overhangs | 2-nt 3' overhangs | Facilitates recognition by Dicer and Argonaute proteins [16] |

| Strand Identity | Guide (antisense) and Passenger (sense) | Determines which strand is used for target recognition [5] |

| Thermodynamic Asymmetry | Difference in base-pairing stability at the 5' ends of the duplex | A key determinant for guide strand selection; the strand with the less stable 5' end is preferentially loaded [17] |

The Role of Dicer in siRNA Biogenesis and Function

Dicer is a specialized RNase III enzyme that initiates the RNAi pathway. Its primary function is to cleave long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) precursors into mature siRNA duplexes [17] [18]. In humans, Dicer functions in concert with double-stranded RNA-binding proteins (dsRBPs) like TRBP and PACT [17].

The mechanism of Dicer involves two distinct RNA binding sites:

- A catalytic site for processing long dsRNA substrates into siRNAs.

- A sensing site on its helicase domain that binds the siRNA product and helps sense its thermodynamic asymmetry [17].

Following dicing, the siRNA undergoes repositioning within the Dicer complex. The initial dsRNA substrate binds to the catalytic arm, but after cleavage, the nascent siRNA product re-localizes to the helicase domain of Dicer. This repositioning is crucial for directional binding and subsequent guide strand selection [17]. In organisms like Drosophila, the Dicer-2–R2D2 heterodimer senses siRNA asymmetry, with R2D2 binding the more stable end and Dicer-2 binding the less stable end, which dictates the orientation for RISC loading [18].

siRNA Mechanism and Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core pathway of siRNA-mediated gene silencing, from dicing to target mRNA degradation.

Diagram 1: The siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing Pathway. This workflow outlines the key steps from long double-stranded RNA processing to mRNA cleavage by the activated RISC.

Guide Strand Selection Mechanism

A critical step in RNAi is the selective loading of the correct guide strand into RISC. The following diagram details the molecular mechanism of strand selection based on thermodynamic asymmetry.

Diagram 2: Mechanism of Guide Strand Selection. Dicer senses the difference in thermodynamic stability at the 5' ends of the siRNA duplex, determining which strand is loaded into RISC as the guide.

Experimental Protocols and Design Considerations

Protocol for In Vitro siRNA-Mediated Gene Knockdown

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for transient gene knockdown in cultured mammalian cells using synthetic siRNA.

Materials:

- Cultured mammalian cells

- Synthetic siRNA (e.g., ON-TARGETplus, Accell)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., cationic lipid-based)

- Opti-MEM or similar serum-free medium

- Normal growth medium

- RNA extraction kit

- qRT-PCR reagents for knockdown validation

Procedure:

- siRNA Design and Preparation: Design siRNA sequences targeting your gene of interest. Follow design rules in Section 4.2. Resuspend synthetic siRNA in provided buffer to create a stock solution (e.g., 20 µM).

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in a 24-well plate at 50–70% confluence in normal growth medium without antibiotics. Incubate at 37°C for 24 hours.

- Transfection Complex Formation:

- Tube A: Dilute 5 µL of 20 µM siRNA stock (final 100 pmol) in 50 µL Opti-MEM.

- Tube B: Dilute 1–2 µL of transfection reagent in 50 µL Opti-MEM. Incubate for 5 minutes.

- Combine solutions from Tubes A and B. Mix gently and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature to allow complex formation.

- Transfection: Add the 100 µL transfection complex dropwise to cells. Gently swirl the plate to distribute evenly.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate cells for 48–72 hours at 37°C.

- Knockdown Validation (48-72 hours): Extract total RNA and perform qRT-PCR to assess target mRNA levels.

- Phenotypic Analysis (72+ hours): Proceed with functional assays (e.g., Western blot, viability, apoptosis) to assess the biological impact of knockdown.

Key Design Considerations for Effective siRNA

Effective siRNA design is critical for maximizing gene silencing and minimizing off-target effects. Modern algorithms (e.g., SMARTselection) use rules derived from large-scale functional studies [5].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Rational siRNA Design

| Parameter | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Target Sequence | Select a region within the mRNA coding sequence or 3' UTR. Avoid regions with high homology to other genes. | Maximizes specificity and reduces off-target silencing [5]. |

| GC Content | Maintain between 30–50%. | Extremely high or low GC content can reduce silencing efficiency and specificity [19]. |

| Thermodynamic Profile | Ensure the 5' end of the intended guide strand has lower binding stability than its 3' end. | Promotes preferential loading of the intended guide strand into RISC [17] [5]. |

| Seed Region (nt 2-8) | Avoid complementarity to off-target transcripts. Use chemical modifications if necessary. | The seed region is critical for initial target binding; managing its sequence reduces off-target effects [5]. |

| Chemical Modifications | Incorporate modifications like 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe) or phosphorothioate (PS). | Enhances nuclease resistance, improves specificity, and reduces immune stimulation [20] [21]. |

Advanced siRNA Structural Variants

While the 21-nt siRNA with 3' overhangs is standard, research has identified potent non-classical structures.

Table 3: Structural Variants of siRNA

| Variant | Structure | Advantages and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Dicer-Substrate siRNA (dsiRNA) | 27-bp duplex with asymmetric design (e.g., 25-nt sense/27-nt antisense strand). | Increased potency as it is processed by Dicer, leading to more efficient RISC loading [16]. |

| Blunt siRNA | 19–25 bp duplex without overhangs. | Can trigger efficient gene silencing, demonstrating flexibility in structural requirements [16]. |

| Asymmetric Design | Structurally asymmetric overhangs (e.g., DNA substitutions in one strand). | Promotes preferential incorporation of the antisense strand into RISC, enhancing specificity [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for siRNA Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Predesigned siRNA (e.g., ON-TARGETplus) | High-quality, chemically modified siRNAs for high-throughput gene silencing. | Rapid knockdown of a single gene or a gene family with minimized off-target effects [5]. |

| Custom siRNA Synthesis | Synthesis of specific siRNA sequences tailored to unique targets. | Targeting specific SNPs, novel transcripts, or non-coding RNAs not covered by predesigned libraries [5]. |

| Transfection Reagents (Cationic Lipids/Polymers) | Form complexes with siRNA to facilitate cellular uptake. | Delivering siRNA into standard cell lines (e.g., HEK-293, HeLa) [5]. |

| Accell siRNA | Chemically modified siRNA for delivery without transfection reagents. | Gene silencing in difficult-to-transfect cells (e.g., primary neurons, immune cells) [5]. |

| siRNA Libraries | Genome-wide or pathway-focused collections of siRNAs. | Large-scale functional genomic screens to identify novel genes involved in a biological process [5]. |

| Positive & Negative Control siRNAs | Validated siRNA against a housekeeping gene and non-targeting sequence. | Optimizing transfection efficiency and controlling for non-sequence-specific effects [5]. |

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) therapeutics represent a revolutionary class of gene-targeted medicines that operate through the natural cellular process of RNA interference (RNAi). These double-stranded RNA molecules, typically 21–23 nucleotides in length, offer a fundamentally distinct mechanism of action compared to traditional small molecules and antibody-based therapeutics [22] [23]. By specifically targeting and silencing disease-causing genes at the post-transcriptional level, siRNA drugs provide researchers with an unprecedented ability to modulate previously inaccessible biological pathways [24]. The core advantages of this technology—exceptional specificity, modular programmability, and the capacity to target "undruggable" genes—are reshaping therapeutic development across diverse disease areas, from genetic disorders to cancer and viral infections [22] [24] [25].

The molecular specificity of siRNA stems from Watson-Crick base pairing, wherein the antisense (guide) strand directs the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences for precise cleavage and degradation [22] [23]. This mechanism enables researchers to target individual gene isoforms with nucleotide-level precision, a capability that remains challenging for conventional small-molecule drugs that typically target protein active sites [24]. The programmable nature of siRNA design allows for rapid development against new targets simply by modifying the oligonucleotide sequence, significantly accelerating the therapeutic discovery pipeline compared to traditional drug modalities [23].

Key Advantages: Quantitative Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of siRNA Therapeutics Versus Traditional Modalities

| Feature | siRNA Therapeutics | Small Molecule Drugs | Monoclonal Antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Specificity | Gene-level specificity via complementary base pairing | Binds protein active sites; limited by protein structure | Binds specific epitopes; limited to extracellular targets |

| Development Timeline | Shorter R&D cycles due to programmable design [26] | Lengthy optimization of chemical structures | Complex development of biological production |

| Druggable Target Space | Targets "undruggable" genes including transcription factors [24] [25] | ~15% of the human genome [22] | Limited to extracellular and cell surface targets |

| Duration of Action | Sustained effects (weeks to months) due to catalytic RISC activity [26] | Short duration (hours to days) requiring frequent dosing | Moderate duration (days to weeks) |

| Therapeutic Applicability | Broad: genetic disorders, cancers, viral infections, metabolic diseases [22] [26] | Extensive but limited by target chemistry | Primarily inflammatory diseases, oncology |

Table 2: Clinical-Stage Examples Demonstrating siRNA Advantages

| siRNA Drug (Target) | Indication | Key Advantage Demonstrated | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patisiran (TTR) | Hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis | First FDA-approved RNAi therapeutic; targets disease-causing gene [22] | Approved (2018) |

| siG12D-LODER (KRAS G12D) | Pancreatic cancer | Targets "undruggable" KRAS mutation [23] | Clinical trials |

| Dual-targeting anti-KRAS/MYC | Solid tumors | Co-silencing of two undruggable oncogenes [25] | Preclinical development |

| Inclisiran (PCSK9) | Hypercholesterolemia | Sustained effects with infrequent dosing [26] | Approved |

| Cond-siRNA (CaN) | Heart failure | Conditionally activated only in diseased cardiomyocytes [27] | Preclinical development |

Application Note 1: Targeting "Undruggable" Oncogenes

Background and Significance

The ability to target traditionally "undruggable" genes represents one of the most significant advantages of siRNA therapeutics. In oncology, key drivers like KRAS and MYC have eluded successful targeting by small molecules for decades due to their protein structures and intracellular locations [25]. KRAS mutations are present in approximately 25% of all human cancers, while MYC is dysfunctional in 50-70% of cancers, making them highly prioritized but challenging therapeutic targets [25].

Experimental Approach: Dual-Targeting Strategy

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate the power of siRNA to simultaneously silence multiple oncogenes. Pecot and colleagues developed a novel "two-in-one" inverted RNAi molecule capable of co-silencing both mutated KRAS and overexpressed MYC [25]. This approach resulted in a remarkable 40-fold improvement in inhibition of cancer cell viability compared to individual siRNA targeting, demonstrating synergistic effects against these critical oncogenic drivers [25].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Oncogene-Targeted siRNA Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Example in Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol-enriched exosomes (Chol/MEs) | Enhanced siRNA delivery via membrane fusion | PLK1 siRNA delivery in colorectal cancer models [24] |

| Inverted RNAi molecules | Enable simultaneous silencing of multiple genes | Dual targeting of KRAS and MYC oncogenes [25] |

| LODER polymers | Localized sustained release of siRNA | siG12D-LODER for KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer [23] |

| GalNAc conjugates | Hepatocyte-specific siRNA delivery | Approved siRNAs for hepatic conditions [22] |

| Electroporation frameworks | Scalable loading of siRNA into exosomes | Capricor's systematic loading approach [28] |

Protocol: Dual-Targeting siRNA Design and Validation

Step 1: Target Sequence Selection

- Identify unique 21-23 nucleotide sequences within KRAS (e.g., mutation hotspots like G12D, G12V) and MYC mRNA

- Verify specificity using NCBI BLAST against human transcriptome to minimize off-target effects [23]

- Select sequences with ~50% GC content, avoiding problematic motifs (e.g., GGGG repeats) [27]

Step 2: Molecular Assembly

- Design inverted siRNA architecture with complementary regions enabling single-molecule assembly

- Incorporate chemical modifications (2'-O-methyl, LNA) to enhance stability and reduce immunostimulation [27]

- Synthesize and purify using standard oligonucleotide synthesis methods

Step 3: In Vitro Validation

- Transfect cancer cell lines (e.g., HCT116 colorectal, pancreatic cancer lines) using appropriate delivery systems

- Assess gene silencing efficiency via RT-qPCR at 48-72 hours post-transfection

- Evaluate functional effects using cell viability assays (MTT, CellTiter-Glo) and apoptosis detection (annexin V staining)

- Confirm pathway modulation through Western blotting for KRAS, MYC, and downstream effectors

Step 4: In Vivo Evaluation

- Formulate siRNA for in vivo delivery (e.g., lipid nanoparticles, exosomal systems)

- Administer to xenograft mouse models via appropriate routes (IV, localized)

- Monitor tumor growth inhibition and assess target engagement in excised tumors

- Evaluate safety profile through histological examination of major organs

Diagram 1: Dual-targeting siRNA mechanism for undruggable oncogenes.

Application Note 2: Conditional siRNA for Cell-Type Specific Silencing

Background and Significance

A critical challenge in therapeutic siRNA development is achieving cell-type specific silencing to minimize off-target effects in healthy tissues. Conditional siRNA (Cond-siRNA) technology addresses this limitation by creating "smart" therapeutics activated only in diseased cells [27]. This approach represents the pinnacle of siRNA programmability, leveraging disease-specific biomarkers to trigger therapeutic activity precisely where needed.

Experimental Approach: Cardiac Hypertrophy Targeting

Gokulnath and colleagues developed a novel Cond-siRNA construct activated by Nppa mRNA, which is specifically upregulated in cardiomyocytes under pathological stress but exhibits low baseline expression in healthy hearts [27]. This Cond-siRNA silences the key pro-hypertrophic gene calcineurin (CaN) only when activated by the Nppa biomarker, creating a feedback loop that automatically attenuates hypertrophic signaling in stressed cardiomyocytes while sparing other cell types [27].

Protocol: Conditional siRNA Design and Implementation

Step 1: Disease-Specific Sensor Identification

- Screen potential sensor mRNAs using disease models (e.g., phenylephrine treatment in cardiomyocytes)

- Validate biomarker specificity through RT-qPCR in diseased vs. healthy tissues

- Select sensor with maximal disease-to-healthy expression ratio (Nppa demonstrated >10-fold induction) [27]

Step 2: Riboswitch Assembly

- Design sensor strand complementary to 31-33 nucleotide segment of biomarker 3' UTR

- Create core strand with complementary segments (11-12 bases) for sensor interaction

- Incorporate therapeutic guide strand targeting gene of interest (e.g., CaN for hypertrophy)

- Optimize thermodynamic properties using Nupack software for nucleic acid structure prediction [27]

Step 3: Specificity Validation

- Transfert Cond-siRNA into target (cardiomyocytes) and non-target (cardiac fibroblasts, T cells) populations

- Induce disease state (phenylephrine treatment) in target cells

- Assess CaN silencing specifically in activated cardiomyocytes via RT-qPCR and Western blot

- Confirm minimal baseline activity in unstimulated cells and non-target cell types

Step 4: Functional Efficacy Assessment

- Measure hypertrophy markers (cell size, ANP secretion) in disease models

- Evaluate NFATc1 nuclear translocation as indicator of CaN pathway activity

- Validate in tissue-on-chip models simulating pathological stress (pressure overload)

Diagram 2: Conditional siRNA mechanism for tissue-specific gene silencing.

Application Note 3: Advanced Delivery Systems for Enhanced Specificity

Background and Significance

The programmability of siRNA extends beyond sequence design to include delivery system engineering, enabling tissue-specific targeting and improved therapeutic indices. Recent advances in delivery platforms have dramatically enhanced the specificity and efficacy of siRNA therapeutics by facilitating targeted cytosolic delivery while minimizing off-target effects [24] [28].

Experimental Approach: Cholesterol-Enriched Exosomes

Zhang et al. engineered cholesterol-enriched exosomes (Chol/MEs) that enable siRNA to bypass endosomal entrapment and directly enter the cytosol via membrane fusion [24]. This delivery platform demonstrated superior gene silencing efficiency compared to conventional transfection agents (Lipofectamine 2000, RNAiMAX), reducing PLK1 expression and achieving remarkable tumor growth inhibition (0.05-fold of PBS control) in preclinical colorectal cancer models [24].

Protocol: Engineered Exosome Production and Application

Step 1: Exosome Engineering

- Transfert 293F cells with plasmids for exosome production

- Modulate cholesterol content in exosomal membranes through metabolic engineering

- Harvest exosomes from cell culture supernatants via differential centrifugation

- Characterize using nanoparticle tracking analysis and Western blotting for exosomal markers

Step 2: siRNA Loading Optimization

- Implement electroporation parameters optimized for siRNA loading

- Assess both scale-up and scale-out strategies for clinical translation [28]

- Determine loading efficiency using fluorescently labeled siRNA and quantification methods

- Validate siRNA integrity post-loading through gel electrophoresis

Step 3: Functional Delivery Validation

- Test cellular uptake in target vs. non-target cell lines using flow cytometry

- Confirm endosomal bypass and direct cytosolic delivery via confocal microscopy

- Evaluate gene silencing potency across multiple siRNA targets

- Compare to commercial transfection reagents for benchmarking performance

Step 4: In Vivo Application

- Administer siRNA-loaded Chol/MEs via appropriate routes (IV, oral for GI cancers)

- Assess biodistribution using near-infrared imaging

- Quantify target engagement in tumors and major organs

- Evaluate safety profile through comprehensive histopathological analysis

Table 4: Advanced Delivery Platforms for Enhanced siRNA Specificity

| Delivery Platform | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol-enriched Exosomes (Chol/MEs) | Membrane fusion enabling direct cytosolic delivery [24] | Bypasses endosomal trapping; reduced immunogenicity; enables oral delivery [24] | PLK1 silencing in colorectal cancer; oral siRNA delivery |

| GalNAc Conjugates | Receptor-mediated endocytosis via asialoglycoprotein receptor | Hepatocyte-specific targeting; clinical validation [22] | Liver-directed therapies (PCSK9, TTR) |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Endocytosis and endosomal release | Broad applicability; FDA-approved formulations | Systemic siRNA delivery; vaccine applications |

| Targeted RNAi Molecules (TRiM) | Component-based modular targeting | Tunable pharmacokinetics and biodistribution | Tissue-specific silencing beyond liver |

Technical Considerations and Troubleshooting

Optimizing Specificity and Reducing Off-Target Effects

Despite the inherent specificity of siRNA, off-target effects remain a significant consideration in experimental design. These primarily occur through two mechanisms: immune stimulation through interferon response and miRNA-like effects due to partial complementarity to untargeted transcripts [22]. To minimize these effects:

- Seed Region Analysis: Utilize BLAST and other computational tools to identify and avoid 7-nucleotide matches within the seed region (positions 2-8) of the guide strand to untargeted mRNAs [23]

- Chemical Modifications: Incorporate 2'-O-methyl modifications particularly in the guide strand seed region to reduce off-target silencing while maintaining on-target activity [27]

- Asymmetric Design: Favor asymmetric duplexes with thermodynamically less stable 5' end of the antisense strand to ensure proper RISC loading [22]

- Concentration Optimization: Identify the lowest effective concentration that induces target gene silencing to minimize nonspecific effects [22]

Protocol: Specificity Validation Workflow

Step 1: In Silico Specificity Screening

- Perform comprehensive BLAST analysis against human transcriptome

- Identify and redesign siRNAs with significant off-target potential

- Utilize prediction algorithms (e.g., Smith-Waterman) for enhanced specificity profiling

Step 2: Transcriptomic Assessment

- Conduct RNA-seq of treated vs. untreated cells

- Analyze differential expression beyond target gene

- Validate potential off-targets through RT-qPCR

- Compare to non-targeting control siRNA treatments

Step 3: Functional Confirmation

- Employ rescue experiments with modified target sequences

- Validate phenotype specificity using orthogonal approaches (CRISPR, antibodies)

- Assess immune activation through interferon-responsive gene expression panels

The unique advantages of siRNA therapeutics—exceptional specificity, modular programmability, and access to previously "undruggable" targets—position this technology as a transformative modality in biomedical research and therapeutic development. The experimental approaches and protocols detailed herein provide researchers with robust frameworks for leveraging these advantages across diverse applications, from oncology to cardiology.

Future directions in siRNA research will likely focus on expanding tissue targeting beyond the liver, enhancing conditional activation strategies for unprecedented specificity, and developing multi-targeting approaches for complex disease pathways. The continued evolution of delivery platforms, combined with increasingly sophisticated siRNA design principles, promises to unlock new therapeutic possibilities and accelerate the translation of siRNA discoveries from bench to bedside.

As the field advances, the integration of siRNA tools with other emerging technologies—including CRISPR-based screening for target identification [29] and organ-on-chip systems for functional validation [27]—will further enhance our ability to precisely modulate disease-relevant genes with minimal off-target effects, ultimately enabling more effective and safer therapeutic interventions for challenging diseases.

Designing and Delivering siRNA: From Rational Sequence Selection to Advanced Delivery Systems

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology has emerged as a powerful tool for targeted gene knockdown in research and therapeutic development. The efficacy of siRNA-mediated silencing is not uniform; it critically depends on the intelligent selection of the target site within the mRNA and the inherent biochemical properties of the siRNA molecule itself. Among these properties, the accessibility of the target mRNA region and the guanine-cytosine (GC) content of the siRNA are two of the most pivotal factors determining success. This application note details evidence-based protocols for identifying accessible mRNA regions and optimizing siRNA GC content, framed within the broader context of a research thesis on siRNA for targeted gene knockdown. The guidance is structured to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with actionable methodologies to enhance the efficiency and specificity of their gene silencing experiments.

The fundamental mechanism of RNA interference (RNAi) begins with the loading of the siRNA guide strand into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The activated RISC then scans the cytosolic mRNA pool to find and cleave a perfectly complementary target sequence [21]. However, the inherent structure of the mRNA presents a significant barrier. Stable secondary structures, such as hairpins and stem-loops, can shield potential target sites, making them inaccessible to RISC binding [30]. Furthermore, the GC content of the siRNA duplex influences its thermodynamic stability and its correct loading into RISC. An overly stable duplex (high GC content) can impede strand separation, a necessary step for RISC activation, while a very unstable duplex (low GC content) may not form properly [31] [32].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the critical decision points and their relationships in the optimal siRNA design process.

Core Design Parameters and Quantitative Criteria

A systematic approach to siRNA design requires adherence to a set of well-established, quantitative sequence and thermodynamic parameters. The table below summarizes the key criteria that should be evaluated for each candidate siRNA sequence.

Table 1: Key Criteria for Effective siRNA Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Feature | Rationale & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 30% - 52% [33] | Balances duplex stability; >60% GC negatively impacts silencing [4]. |

| Sequence Length | 21-23 nucleotides [19] | Standard length for RISC incorporation and target recognition. |

| Thermodynamic Asymmetry | Unstable 5' end (A/U-rich) of the guide strand [30] | Promotes correct guide strand loading into RISC, improving efficiency by 2-5 fold. |

| Position-Specific Nucleotides | 'A' at position 19, 'U' at position 10 [33] | Position-specific preferences correlated with high silencing efficacy. |

| Avoidance of Repeats | No CCCC or GGGG stretches [4] | Prevents synthetic challenges and potential structural issues. |

| Off-Target Filtering | < 78% query coverage with other genes via BLAST [33] | Minimizes homology-driven off-target effects. |

Adhering to these parameters during the initial design phase significantly increases the probability of identifying highly functional siRNAs. It is recommended to design and synthesize multiple siRNA candidates targeting different regions of the same mRNA to empirically confirm the robustness of the knockdown [31].

Protocol: Computational Screening for Optimal siRNA

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for the in-silico design and selection of siRNA candidates, integrating the criteria from Table 1.

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| NCBI Nucleotide Database | Repository for retrieving the target mRNA sequence in FASTA format [19]. |

| siRNA Design Software (e.g., siDirect, Ambion/Invitrogen Designer, GenScript's tool) | Algorithms to generate candidate siRNA sequences based on established rules [30] [33]. |

| Secondary Structure Prediction Tool (e.g., RNAfold, OligoWalk) | Predicts mRNA target site accessibility and local free energy (ΔG) [30] [34]. |

| BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) | Checks sequence specificity to minimize off-target effects [31] [33]. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock, GROMACS) | Models siRNA interaction with Argonaute-2 (AGO2) to predict binding affinity and silencing potential [19] [34]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

mRNA Sequence Retrieval:

- Obtain the complete coding DNA sequence (CDS) of your target gene in FASTA format from a reliable database such as the NCBI Nucleotide Database (e.g., Accession Number: NM_004248.3) [19].

Initial siRNA Candidate Generation:

- Input the FASTA sequence into a specialized siRNA design software.

- The software will scan the mRNA, typically identifying 21-nucleotide sequences that start with an "AA" dinucleotide and filtering them based on GC content (aim for 30-52%) [31] [33].

- The output will be a list of potential siRNA candidate sequences.

Refinement Based on Target Site Accessibility:

- To prioritize candidates, analyze the predicted accessibility of their target sites on the mRNA.

- Use tools like OligoWalk (part of the RNAstructure package) or RNAfold.

- Action: Calculate the hybridization energy (ΔG) between the siRNA guide strand and its target mRNA. Favorable (more negative) ΔG values (e.g., -31.1 to -37.3 kcal/mol) indicate stronger and more accessible binding [34].

- Action: Visually inspect the predicted secondary structure of the mRNA. Prioritize target sites located in regions with low local free energy, which are likely to be open and unstructured, rather than within stable hairpins or stem-loops [30].

Specificity and Off-Target Assessment:

- Perform a BLAST search of both the sense and antisense strands of each candidate siRNA against the appropriate genome database (e.g., human, mouse, rat).

- Action: Exclude any sequences with >16-17 contiguous base pairs of homology to other coding sequences or a query coverage of 78% or higher with non-target genes [31] [33].

Advanced Computational Validation (Optional but Recommended):

- For high-confidence leads, use molecular docking to simulate the interaction between the siRNA guide strand and the human Argonaute-2 (AGO2) protein.

- Action: Retrieve the 3D structure of AGO2 from a database like the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Action: Docking scores (e.g., between -330 and -351 kcal/mol) indicate efficient RISC loading. Follow this with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., using GROMACS) to confirm the structural stability of the siRNA-AGO2 complex over time, with stable Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values (e.g., 2.1–2.6 Å) being a positive indicator [19] [34].

Protocol: Experimental Validation of siRNA Efficacy

After in-silico selection, experimental validation is essential to confirm silencing efficiency and specificity.

Materials

- Cell Line: Relevant to your research (e.g., A549 for lung cancer studies [33]).

- siRNA Transfection Reagent: Such as RNAiMax or other lipid-based agents [35].

- Validated siRNA Sequences: Synthesized candidate siRNAs, a non-targeting scrambled negative control siRNA, and a positive control siRNA (e.g., against a housekeeping gene) [35] [33].

- qRT-PCR Kit: For quantifying mRNA knockdown.

- Western Blot Equipment: For assessing protein-level knockdown.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Plate cells at 40-80% confluency in appropriate growth media without antibiotics 24 hours before transfection [35].

- Complex the candidate siRNAs with the transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. A reverse transfection protocol, where cells are plated directly onto the siRNA-reagent complexes, can save time and sometimes improve efficiency [35].

- Critical: Transfect multiple siRNA candidates (2-4) targeting different regions of the same mRNA to ensure consistent biological effects and confirm on-target activity [31].

- Include both negative control (scrambled sequence) and positive control siRNAs in every experiment.

Optimization of Transfection Conditions:

- Titrate the siRNA concentration (e.g., 1-50 nM) to find the lowest dose that achieves maximal knockdown, thereby minimizing potential off-target effects and cytotoxicity [35].

- If cytotoxicity is observed, consider replacing the transfection media with fresh growth media 8-24 hours post-transfection.

Efficiency Measurement:

- mRNA Knockdown: Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-transfection. Isolate total RNA and perform quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to measure remaining target mRNA levels, normalized to a housekeeping gene. Effective siRNAs should achieve ≥70% knockdown of the target mRNA [35].

- Protein Knockdown: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection. Analyze protein expression levels via Western blot or other immunoassays. The time to maximal protein knockdown depends on the protein's half-life [35].

The relationship between optimal design, successful RISC loading, and mRNA cleavage is summarized in the following pathway diagram.

The strategic selection of accessible mRNA target sites and the careful management of siRNA GC content are foundational to successful gene silencing. By following the detailed protocols and adhering to the quantitative design criteria outlined in this application note, researchers can systematically enhance the efficacy and reliability of their siRNA-based experiments. This structured approach, which integrates robust computational screening with rigorous experimental validation, is essential for generating high-quality data, advancing functional genomics research, and accelerating the development of siRNA therapeutics.

Within the realm of targeted gene knockdown research, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) represent a powerful therapeutic tool. However, their application is contingent upon overcoming inherent challenges related to stability and bioavailability. Nuclease degradation and off-target effects can significantly hinder their efficacy. Consequently, strategic chemical modification is not merely an enhancement but a fundamental requirement for developing viable siRNA-based therapeutics. This Application Note delineates the critical roles of three cornerstone chemical modifications—2'-O-Methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-Fluoro (2'-F), and phosphorothioate (PS) linkages—in optimizing siRNA performance. We provide a synthesized overview of quantitative findings, detailed protocols for introducing these modifications, and essential resources for the scientific practitioner, all framed within the context of a robust research and development workflow.

Modification Profiles and Quantitative Impact

Extensive research has been dedicated to understanding how specific chemical modifications influence the stability, potency, and specificity of siRNAs. The data summarized in the following tables provide a comparative overview of the key modifications discussed in this note.

Table 1: Comparison of Key siRNA Chemical Modifications

| Modification | Primary Function | Impact on Stability | Impact on Potency | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2'-O-Methyl (2'-OMe) | Ribose modification; enhances nuclease resistance [36]. | Significantly improves serum stability; increasing 2'-OMe content enhances potency and duration in vivo [37]. | Can negatively impact activity at specific positions (e.g., guide strand position 14, 3' terminus of 20-mer guides) [37]. | Tolerability is highly position-dependent [37] [38]. |

| 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) | Ribose modification; confers nuclease resistance [36]. | Improves stability against nucleases [37]. | Generally well-tolerated; can partially compensate for negative effects of 3' terminal 2'-OMe in 20-mer guides when placed at position 5 [37]. | Often used in an alternating pattern with 2'-OMe [37]. |

| Phosphorothioate (PS) | Backbone modification; replaces non-bridging oxygen with sulfur [36]. | Improves resistance to nucleases, particularly exonucleases; enhances cellular uptake via hydrophobicity [39] [36]. | Extensive modification can reduce gene-silencing activity and increase cytotoxicity [36]. | Chirality matters: Rp at 5' end and Sp at 3' end of guide strand improve Ago2 loading and pharmacokinetics [39]. |

The quantitative impact of these modifications is critical for rational design. The table below consolidates key experimental findings on their effect on siRNA stability.

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Modification Efficacy

| Modification / Combination | Experimental Context | Key Quantitative Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3' Terminal 2'-OMe (vs. 2'-F) | Fully modified, asymmetric siRNAs with 20-mer guide strands. | Reduced activity for >60% of sequences tested; IC50 increased up to 7.3-fold [37]. | Davis et al., 2020 |

| 2'-OMe + Cationic Oligosaccharide (ODAGal4) | Serum degradation assay with HPRT1-targeting siRNA. | Half-life increased from 5.50 h (unmodified) to 9.98 h [36]. | Sasaki et al., 2020 |

| PS + Cationic Oligosaccharide (ODAGal4) | Serum degradation assay with fully PS-modified siRNA and ODAGal4. | Half-life >15 times longer than unmodified siRNA without ODAGal4 [36]. | Sasaki et al., 2020 |

| Combined 2'-OMe & PS (MS) | CRISPR gRNA for co-electroporation with Cas9 mRNA. | Enabled efficient gene editing where unmodified gRNAs failed; increased nuclease resistance [40]. | Basila et al., 2017 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Introducing 2'-O-Methyl and 2'-Fluoro Modifications via Solid-Phase Synthesis

This protocol outlines the procedure for synthesizing oligonucleotides with site-specific 2'-OMe and 2'-F modifications using solid-phase phosphoramidite chemistry, which is suitable for producing siRNAs and guide RNAs up to approximately 100 nucleotides [41] [40].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Phosphoramidites: Standard 2'-ACE-protected ribo-, 2'-O-methyl-, and 2'-fluoro-phosphoramidites (e.g., from Glen Research or ChemGenes).

- Solid Support: Controlled-pore glass (CPG) or polystyrene support with the first nucleoside attached.

- Activating Agent: 0.25 M 5-Benzylthio-1H-tetrazole (BTT) in acetonitrile (ACN).

- Oxidizer Solution: 0.02 M Iodine in THF/Pyridine/Water.

- Capping Solutions: Cap A (Acetic Anhydride/Pyridine/THF) & Cap B (1-Methylimidazole/Pyridine/THF).

- Deprotection Reagent: Methylamine in aqueous ethanol or AMA (Ammonium Hydroxide / 40% Aqueous Methylamine).

- Solvents: Anhydrous acetonitrile, Dichloromethane (DCM).

- Synthesis Equipment: Automated DNA/RNA synthesizer.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Preparation: Prime the synthesizer and reagent lines with anhydrous acetonitrile. Load the appropriate phosphoramidites and the solid support containing the 3'-terminal nucleoside into the instrument.

- Detritylation: Flush the column with 3% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) in DCM for 25-35 seconds to remove the 5'-DMT protecting group, then wash with ACN.

- Coupling: Deliver the designated phosphoramidite (standard, 2'-OMe, or 2'-F) and the activating agent (BTT) simultaneously to the column. Couple for 2-5 minutes depending on the specific phosphoramidite and sequence.

- Oxidation: Flush the column with the standard iodine oxidizer for 15-30 seconds to convert the phosphite triester to a phosphate triester. For a Phosphorothioate (PS) linkage, substitute the oxidizer with a sulfurization reagent (e.g., 0.05 M solution of DDTT in ACN).

- Capping: Flush the column with Cap A and Cap B solutions simultaneously for 10-15 seconds each to block unreacted 5'-OH groups from further elongation.

- Cycle Completion: Repeat steps 2-5 for each subsequent nucleotide until the full sequence is assembled.

- Cleavage and Deprotection: Cleave the oligonucleotide from the support and remove the base and 2'-ACE protecting groups by treating the controlled-pore glass with methylamine/AMM at a specific temperature (e.g., 65°C for 15-30 minutes) [40].

- Purification and Analysis: Desalt the crude oligonucleotide (e.g., via size-exclusion chromatography). For higher purity, purify by preparative anion-exchange HPLC or reverse-phase HPLC. Analyze the final product by LC-MS or MALDI-TOF for identity and purity confirmation [41] [40].

Protocol: Serum Stability Assay for Modified siRNAs

This protocol describes a standard method for evaluating the nuclease resistance of chemically modified siRNAs in serum, a critical test for predicting in vivo performance [36].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Test siRNA: Chemically modified siRNA duplex, resuspended in nuclease-free buffer.

- Control siRNA: Unmodified or differently modified siRNA duplex of the same sequence.

- Serum: Mouse, human, or fetal bovine serum (FBS).

- Stop Solution: 8 M Urea, 50 mM EDTA, 0.05% Bromophenol Blue, 0.05% Xylene Cyanol.

- Proteinase K

- Equipment: Water bath or incubator (37°C), gel electrophoresis system, gel imager.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a mixture containing serum (e.g., 90% final concentration) and pre-warm it to 37°C. Add the siRNA duplex to a final concentration of 0.5-1 µM to initiate the degradation reaction. Incubate at 37°C.

- Time-Point Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 hours), withdraw an aliquot of the reaction mixture.

- Reaction Termination: Immediately mix the aliquot with an equal volume of Stop Solution. Add Proteinase K (e.g., 1 mg/mL final concentration) and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to digest serum proteins.

- Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis: Load the processed samples onto a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 15%) or an agarose gel. Run the gel at a constant voltage until sufficient separation of intact siRNA from degradation products is achieved.

- Visualization and Quantification: Stain the gel with a nucleic acid stain (e.g., SYBR Gold) and image using a gel documentation system. Quantify the band intensity of the intact siRNA duplex.

- Data Analysis: Plot the percentage of remaining intact siRNA against time. Calculate the half-life of the siRNA by fitting the data to a first-order decay model or an exponential decay function.

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing, creating, and testing chemically modified siRNAs, as detailed in the protocols above.

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing chemically modified siRNAs.

The strategic placement of modifications is critical for success. The subsequent diagram outlines a decision pathway for selecting the appropriate modification based on the desired outcome, incorporating findings on positional tolerability.

Diagram 2: Decision pathway for selecting chemical modifications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the protocols and strategies outlined in this note relies on access to high-quality, specialized reagents. The following table lists key resources for siRNA modification research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for siRNA Modification

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| 2'-OMe & 2'-F Phosphoramidites | Building blocks for solid-phase synthesis of modified RNA oligonucleotides. | Commercially available from vendors like Glen Research, ChemGenes, and Sigma-Aldrich. |

| Cationic Oligosaccharide (ODAGal4) | Binds major groove of siRNA duplex; synergistically enhances stability, especially with PS modifications [36]. | Synthesized as described in Sasaki et al., 2020 [36]. |

| Chiral (stereodefined) PS Reagents | For introducing phosphorothioate linkages with specific Rp or Sp configuration to improve Ago2 loading and pharmacokinetics [39]. | Specialized phosphoramidites or sulfurizing agents (e.g., DDTT). |

| Automated Oligonucleotide Synthesizer | Instrument for automated solid-phase synthesis of modified and unmodified oligonucleotides. | Instruments from vendors like Biolytic, GE Healthcare, and K&A Labs. |

| Stability Assay Components | For evaluating nuclease resistance of modified siRNAs in biologically relevant conditions. | Commercial sera (e.g., FBS from Gibco), Proteinase K (e.g., from Roche). |

The therapeutic application of small interfering RNA (siRNA) for targeted gene knockdown represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research and drug development. siRNA operates by harnessing the endogenous RNA interference (RNAi) pathway, where the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) is guided by the siRNA to complementary mRNA sequences, resulting in their cleavage and degradation, thereby preventing translation of the target protein [42] [43]. However, the major hurdle confronting siRNA therapeutics is the efficient and specific delivery of these nucleic acids to target cells and tissues. Naked siRNA is susceptible to rapid nuclease degradation, suffers from poor cellular uptake, and can elicit unintended immune responses [44] [43] [45]. Consequently, the development of sophisticated delivery platforms is paramount to the success of RNAi-based therapies. This application note details the core delivery strategies—Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), GalNAc conjugates, and Viral Vectors—framed within the context of siRNA research for targeted gene knockdown.

The three primary delivery platforms offer distinct mechanisms for siRNA delivery, each with unique advantages and limitations. Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) are multi-component, spherical nanoscale carriers that encapsulate and protect siRNA, facilitating cellular uptake and endosomal escape [42] [43]. GalNAc (N-acetylgalactosamine) conjugates represent a ligand-based approach, where siRNA is directly conjugated to a trivalent GalNAc moiety that selectively targets the Asialoglycoprotein Receptor (ASGPR) highly expressed on hepatocytes [44]. Viral Vectors, such as those based on Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV), are engineered viruses designed to deliver genetic material encoding for short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that are processed into siRNAs inside the cell [46].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key siRNA Delivery Platforms

| Feature | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | GalNAc Conjugates | Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Nanoparticle encapsulation and cellular endocytosis [43] | Receptor-mediated endocytosis via ASGPR [44] | Viral infection and transduction leading to sustained shRNA expression [46] |

| Primary Application | Hepatocyte & non-hepatocyte targets (e.g., HSCs); vaccines [42] [47] | Highly specific hepatocyte delivery [44] [48] | Long-term gene silencing; research applications [46] |

| Key Advantage | Versatility in targeting; high payload capacity; proven clinical success [42] [43] | Exceptional hepatocyte specificity; simple, well-defined chemistry; subcutaneous administration [44] | Potentially durable, long-lasting silencing effect from a single dose [46] |

| Key Limitation | Potential for off-target accumulation; complex formulation [42] [49] | Restricted primarily to liver hepatocytes [49] [45] | Risk of immunogenicity; limited payload capacity; potential for genomic integration [43] [46] |

| Clinical Status | Multiple approved drugs (e.g., Patisiran) and vaccines [42] [43] | Multiple approved drugs (e.g., Givosiran) and late-stage candidates [44] [42] | Widely used in gene therapy; some concerns for RNAi applications (e.g., oncogenesis) [50] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Delivery Platforms from Preclinical Studies

| Platform / Specific Technology | Target Gene / Model | Key Efficacy Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| LNP (AA-T3A-C12 lipidoid) | HSP47 / CCl4-induced mouse liver fibrosis model [47] | Gene Silencing (HSP47 protein) | ~65% knockdown [47] |

| LNP (AA-T3A-C12 lipidoid) | HSP47 / CCl4-induced mouse liver fibrosis model [47] | Collagen Deposition Reduction | Significant reduction vs. MC3 LNP [47] |

| GalNAc-LNP (GL6 Design) | ANGPTL3 / LDLR-deficient NHP [48] | Liver Editing Efficiency (CRISPR) | 61% editing (vs. 5% without ligand) [48] |

| GalNAc-LNP (GL6 Design) | ANGPTL3 / Wild-type NHP [48] | Protein Reduction (ANGPTL3) | 89% reduction at 6 months [48] |

| Galactose-Liposome (Gal-LipoNP) | Fas / ConA-induced mouse hepatitis model [50] | Hepatoprotection (Serum ALT/AST) | Significant reduction vs. controls [50] |

Key Principles and Mechanisms

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) and Targeted Delivery