Sequencing Platform Accuracy in 2025: A Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research and Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform accuracy, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Sequencing Platform Accuracy in 2025: A Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform accuracy, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of short-read and long-read technologies, examines their specific applications in areas like pharmacogenomics and cancer research, and offers troubleshooting guidance for common accuracy challenges. The analysis includes a direct, evidence-based comparison of leading platforms—including Illumina, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore, and emerging competitors—evaluating their performance in variant calling, coverage of challenging genomic regions, and suitability for clinical validation. The goal is to empower professionals in selecting the optimal sequencing technology to ensure data integrity and reliability in research and diagnostic settings.

The Accuracy Landscape: Understanding Sequencing Generations and Core Technologies

The evolution of DNA sequencing technology represents one of the most transformative progressions in modern biological science. The journey from first-generation Sanger sequencing to massively parallel next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally reshaped research capabilities, diagnostic medicine, and our understanding of genomic complexity. This shift is not merely incremental but represents a fundamental paradigm change from linear, targeted analysis to comprehensive, genome-wide investigation. The transition between these technologies is characterized by dramatic improvements in throughput, cost-efficiency, and scalability, enabling research applications that were previously inconceivable. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the technical capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of each platform is crucial for experimental design, resource allocation, and accurate data interpretation in genomic medicine.

Technical Comparison: Mechanism, Scale, and Output

The core distinction between Sanger sequencing and NGS lies in their underlying biochemistry and detection architecture. Sanger sequencing, known as the chain-termination method, relies on dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs) to randomly terminate DNA synthesis during in vitro replication, producing fragments of varying lengths that are separated by capillary electrophoresis to reveal the DNA sequence [1]. This method generates a single, long contiguous read per reaction, with exceptional per-base accuracy for focused targets [1].

In contrast, massively parallel sequencing employs diverse chemistries to simultaneously sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments [2] [3]. The most prevalent approach is Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), which utilizes fluorescently-labeled, reversible terminators that are incorporated one nucleotide at a time across millions of clustered DNA fragments on a solid surface [1]. After each incorporation cycle, imaging captures the fluorescent signal, followed by cleavage of the terminator to enable the subsequent cycle [3]. This massively parallel approach generates enormous volumes of short-read data that computationally assemble into a comprehensive genomic picture.

Table 1: Fundamental Technical Specifications Comparing Sanger and NGS Platforms

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Method | Chain termination with ddNTPs [1] | Massively parallel sequencing (e.g., SBS, ligation, ion detection) [1] |

| Throughput | Low to medium (individual samples/small batches) [1] | Extremely high (entire genomes/exomes/multiplexed samples) [1] |

| Read Length | 500-1000 bp (long contiguous reads) [1] | 50-600 bp (typically shorter reads) [2] [1] |

| Output per Run | Single sequence per reaction [1] | Millions to billions of short reads [1] |

| Human Genome Cost | ~$3 billion (Human Genome Project) [2] | Under $1,000, approaching $100 [2] [4] |

| Time per Human Genome | 13 years (Human Genome Project) [2] | Hours to days [2] |

| Detection Sensitivity | Limited for variants >15-20% allele frequency [1] | Can detect variants at 1-5% allele frequency [1] |

Table 2: Accuracy Metrics and Quality Assessment

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Per-Base Accuracy | >99.999% (Q50) for central read region [1] | Varies by platform; ~99.9% (Q30) for Illumina SBS [5] |

| Error Profile | Minimal; primarily sample preparation artifacts | Platform-specific (e.g., substitution errors, homopolymer challenges) [3] |

| Overall Accuracy Method | Single read confidence [1] | Statistical confidence from deep coverage (e.g., 30x for WGS) [1] |

| Quality Score Definition | Phred score: Q20 = 1/100 error (99% accuracy) [5] | Phred-like algorithm: Q30 = 1/1000 error (99.9% accuracy) [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Data

Protocol for NGS Accuracy Assessment: The Correctable Decoding Sequencing Approach

Recent research has focused on overcoming inherent NGS error rates through innovative biochemical and computational approaches. The correctable decoding sequencing strategy exemplifies this effort, proposing a duplex sequencing protocol with a conservative theoretical error rate of 0.0009%, surpassing even traditional Sanger sequencing accuracy [6].

Methodology: This approach utilizes a dual-nucleotide sequencing-by-synthesis method employing both natural nucleotides and cyclic reversible terminators (CRTs) with blocked 3'-OH groups [6]. The template is sequenced in two parallel runs with different dual-nucleotide combinations (e.g., AT/CG, AC/GT). In each cycle, the number of incorporated nucleotides generates signal intensities proportional to incorporation events. The resulting two-digit code strings from both runs are computationally aligned and decoded to deduce the precise sequence [6].

Experimental Workflow:

- Library Preparation: DNA fragmentation and adapter ligation

- Cluster Generation: Bridge amplification on flow cell surface

- Sequencing Cycles: Sequential addition of dual-nucleotide mixtures (natural + CRT)

- Signal Detection: Imaging after each incorporation cycle

- Decoding Algorithm: Computational alignment of two encoding sets for error correction

This method effectively addresses homopolymer sequencing challenges and significantly improves raw accuracy, demonstrating the potential for identifying rare mutations in cancer and other biomedical applications [6].

Whole Exome Sequencing Platform Comparison

A 2024 study systematically evaluated the impact of sequencing platforms and bioinformatics pipelines on Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) results, providing critical benchmarking data for platform selection [7].

Experimental Design: Researchers utilized the reference standard HD832 (containing ~380 variants across 152 cancer genes) and normal sample HG001. The same libraries were split and sequenced across three platforms: NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina), NextSeq 550 (Illumina), and GenoLab M (GeneMind). Technical replicates assessed reproducibility, and seven variant-calling pipelines were evaluated [7].

Key Findings:

- Platform Performance: All platforms generated high-quality data suitable for variant detection, with minimal platform-specific biases

- Coverage Uniformity: Consistent coverage across target regions observed regardless of platform

- Variant Calling Concordance: High concordance for SNP calls across platforms (>99%), with greater variability in indel detection

- Pipeline Impact: Bioinformatics pipelines exerted greater influence on variant calling accuracy than platform choice itself

This comprehensive assessment highlights that while modern NGS platforms deliver comparable high-quality data, bioinformatics pipeline selection remains a critical factor in data interpretation accuracy [7].

Application-Based Platform Selection

The choice between Sanger and NGS technologies is primarily determined by the specific research question, scale of investigation, and required resolution. Each platform occupies distinct but complementary niches in modern genomic research and clinical diagnostics.

Table 3: Optimal Applications for Sanger vs. NGS Technologies

| Research Goal | Recommended Technology | Rationale | Typical Coverage/Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Gene Variant Confirmation | Sanger Sequencing [1] | Gold-standard accuracy for defined targets; operational simplicity [1] | Single read spanning entire amplicon |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | NGS [2] [1] | Comprehensive variant discovery; cost-effective at scale [2] | 30x mean coverage [1] |

| Rare Variant Detection (<5% AF) | NGS with deep coverage [1] | Statistical power from ultra-deep sequencing (>1000x) [1] | 500-1000x for liquid biopsies [2] |

| Whole Exome Sequencing | NGS [7] [1] | Focused analysis of coding regions; balance of cost and yield [7] | 100x mean coverage |

| RNA Expression (Transcriptomics) | NGS (RNA-Seq) [1] | Quantitative expression and splice variant analysis [1] | 20-50 million reads/sample |

| Clone Validation / QC | Sanger Sequencing [1] | Long reads verify plasmid constructs completely [1] | Single read per clone |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of sequencing technologies requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each platform and application. The following solutions represent core components of modern sequencing workflows.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sequencing Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Platform Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Reversible Terminators | Reversible termination for SBS; enables one-base incorporation per cycle [3] | NGS (Illumina, GenoLab M) |

| DNA Polymerase Enzymes | Catalyzes template-directed DNA synthesis during sequencing [3] | Sanger & NGS |

| Universal Adapters | Platform-specific sequences enabling fragment binding to flow cells [3] | NGS |

| Barcoded Adapters | Unique molecular identifiers for sample multiplexing [1] | NGS |

| Flow Cells | Solid surfaces with lawn of primers for cluster generation [3] | NGS |

| Exome Capture Kits | Solution-based hybridization to enrich coding regions (e.g., SureSelect) [7] | NGS (WES) |

| Emulsion PCR Reagents | Water-in-oil emulsion for clonal amplification on beads [3] | NGS (Ion Torrent, SOLiD) |

| Capillary Array Cartridges | Separation matrix for fragment size separation [1] | Sanger |

The generational shift from Sanger to massively parallel sequencing has provided researchers and drug development professionals with an unprecedented toolbox for genomic investigation. Rather than representing competing technologies, these platforms form a complementary ecosystem where Sanger sequencing provides the gold-standard validation for focused targets, while NGS enables unbiased discovery at genome-wide scale. The declining cost trajectory—from billions to under $1000 per genome—has democratized access to comprehensive genomic analysis, fueling advancements in personalized medicine, cancer genomics, and rare disease diagnosis [2] [4].

Strategic platform selection requires careful consideration of throughput requirements, target complexity, variant frequency, and bioinformatics capabilities. For clinical applications requiring the highest possible accuracy for defined regions, Sanger remains indispensable. For discovery-phase research, biomarker identification, or comprehensive genomic profiling, NGS provides unparalleled depth and breadth. As sequencing technologies continue evolving toward third-generation long-read platforms and emerging $100 genome solutions, this generational shift will continue to expand the boundaries of genomic medicine, enabling increasingly sophisticated research and therapeutic development [2] [4].

In the landscape of genomic research, the core chemistry principles behind DNA sequencing platforms directly determine their performance in accuracy, throughput, and application suitability. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate technology hinges on a clear understanding of three principal chemistries: Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), Sequencing by Ligation (SBL), and Sequencing by Binding (SBB). Each method employs a distinct biochemical mechanism to decode DNA, leading to trade-offs in read length, accuracy, cost, and the ability to resolve complex genomic regions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these chemistries, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform platform selection for accuracy-focused research within a broader thesis on sequencing technology evaluation.

Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS)

Sequencing by Synthesis is a foundational method used in many prevalent next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms. It determines the DNA sequence by monitoring the polymerase-mediated incorporation of nucleotides into a growing DNA strand in real-time or through cyclic reactions [8] [9].

Core Principle and Workflow

The SBS process involves synthesizing a complementary DNA strand one base at a time and detecting which base is incorporated at each step. Detection methods vary, primarily between optical and non-optical systems [10].

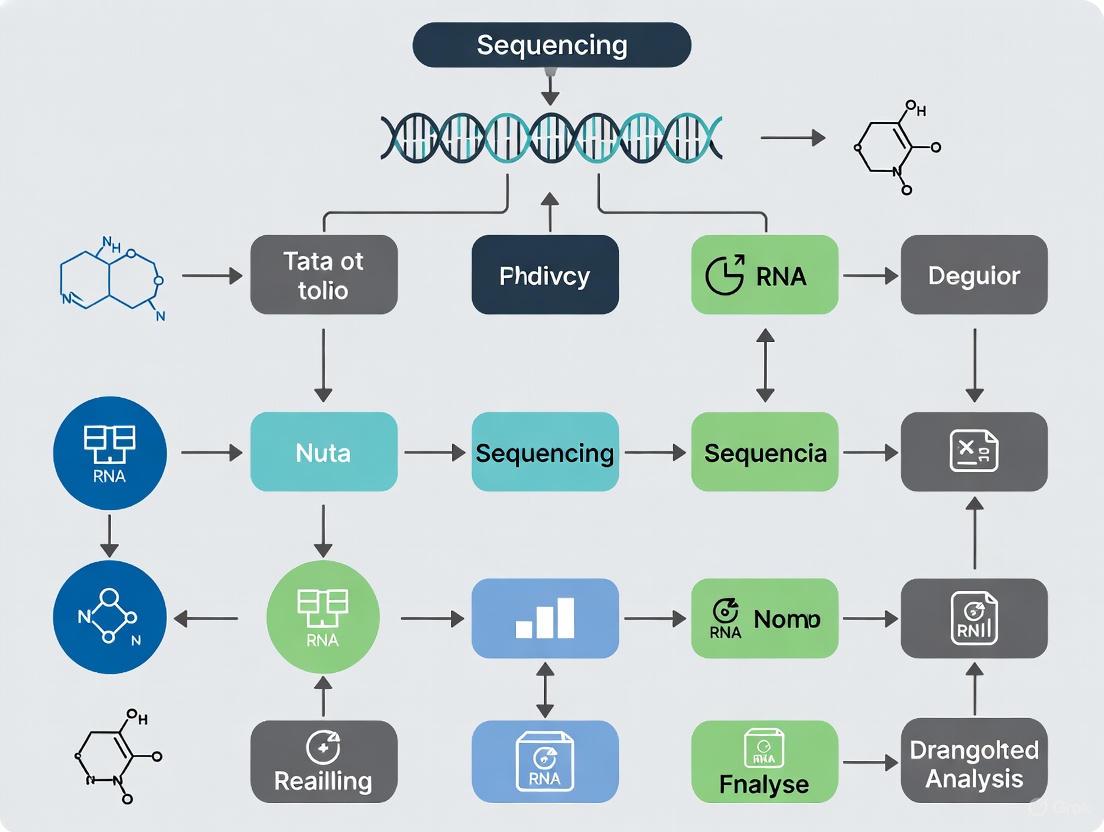

Diagram 1: Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) core workflow. The process cycles through nucleotide addition and detection, branching into optical (e.g., fluorescent dyes) or non-optical (e.g., ion detection) methods.

Key SBS Platforms and Performance

Different SBS platforms utilize unique approaches for signal detection during nucleotide incorporation.

Table 1: Key Sequencing by Synthesis Platforms and Specifications

| Platform | Core Detection Principle | Read Length | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina [11] [8] | Fluorescently-labeled, reversible terminator nucleotides | 36-300 bp | High accuracy (>99%), high throughput, cost-effective | Short reads struggle with repetitive regions |

| Ion Torrent [11] | Hydrogen ion (H+) release (semiconductor sequencing) | 200-400 bp | Rapid sequencing, no optical system needed | Homopolymer errors, signal decay in long homopolymers |

| 454 Pyrosequencing [11] | Pyrophosphate (PPi) release (bioluminescence) | 400-1000 bp | Longer reads than early SBS | Insertion/deletion errors in homopolymers |

| PacBio SMRT [11] [12] | Real-time fluorescence in zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) | 10,000-25,000 bp (long reads) | Very long reads, detects base modifications | Higher cost, historically higher error rates (improved with HiFi) |

Sequencing by Ligation (SBL)

Sequencing by Ligation employs DNA ligase, rather than polymerase, to identify the sequence of a DNA template. It relies on the specificity of ligase to join complementary oligonucleotides to the template [8] [9].

Core Principle and Workflow

This method uses a pool of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes that competitively bind and ligate to the sequencing primer. The identity of the base(s) is determined by the specific probe that is successfully ligated.

Diagram 2: Sequencing by Ligation (SBL) core workflow. The cycle involves probe hybridization, ligation, fluorescence detection, and cleavage to reset the template for the next round.

Key SBL Platforms and Performance

SBL is known for high accuracy in calling bases but typically produces shorter reads.

Table 2: Key Sequencing by Ligation Platforms and Specifications

| Platform | Core Technology | Read Length | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOLiD [11] | Sequencing by Oligonucleotide Ligation and Detection | ~75 bp | High accuracy due to two-base encoding | Very short reads, struggles with palindromic sequences |

| DNA Nanoball [10] [11] | Ligation-based sequencing on self-assembled DNA nanoballs | 50-150 bp | High data density on flow cell | Complex workflow, multiple PCR cycles required |

Sequencing by Binding (SBB)

Sequencing by Binding is a more recent chemistry that decouples the nucleotide binding and incorporation steps. This separation aims to enhance the accuracy of base identification [9].

Core Principle and Workflow

SBB involves cycles where fluorescently-labeled nucleotides bind transiently to the polymerase-DNA complex for detection but are not incorporated. This is followed by a separate step where unlabeled nucleotides are incorporated to extend the DNA strand.

Diagram 3: Sequencing by Binding (SBB) core workflow. The key distinction is the separation of the fluorescent binding/detection step from the actual nucleotide incorporation step.

Key SBB Platforms and Performance

SBB chemistry is designed to reduce incorporation errors and improve performance in repetitive sequences.

Table 3: Key Sequencing by Binding Platforms and Specifications

| Platform | Core Technology | Read Length | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio Onso [11] | Sequencing by Binding (SBB) | 100-200 bp (short reads) | High accuracy, uses native nucleotides | Higher cost compared to some SBS platforms |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Independent benchmarking studies and internal analyses by manufacturers provide critical data for comparative assessment. Key metrics include variant calling accuracy, coverage uniformity, and performance in challenging genomic regions.

Accuracy Benchmarking Against NIST Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) benchmarks provide a standard for evaluating sequencing platform accuracy [13].

Experimental Protocol: Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) Benchmarking

- Sample: GIAB HG002 reference genome (NIST v4.2.1 benchmark) [13].

- Platforms Compared: Illumina NovaSeq X Plus (SBS) vs. Ultima Genomics UG 100 (SBS) [13].

- Method: WGS data generated on each platform. Illumina data analyzed at 35x coverage with DRAGEN v4.3. Ultima data sourced from a public dataset at 40x coverage, analyzed with DeepVariant [13].

- Analysis: Variant calls (SNVs, indels) from each platform are compared against the high-confidence NIST benchmark to count false positives and false negatives. Performance is assessed across the entire genome and in challenging regions (e.g., homopolymers, GC-rich areas) [13].

Table 4: Comparative WGS Benchmarking Data (NovaSeq X vs. UG 100)

| Performance Metric | Illumina NovaSeq X Series (SBS) | Ultima UG 100 (SBS) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNV Errors [13] | Baseline (6x fewer) | 6x more | Compared against full NIST v4.2.1 benchmark |

| Indel Errors [13] | Baseline (22x fewer) | 22x more | Compared against full NIST v4.2.1 benchmark |

| Genome Coverage [13] | 100% of NIST benchmark | ~95.8% (HCR masks 4.2%) | UG "High-Confidence Region" (HCR) excludes low-performance areas |

| Challenging Regions [13] | Maintains high coverage/accuracy | Coverage drop in mid/high GC-rich regions; indel accuracy decreases in homopolymers >10 bp | HCR excludes homopolymers >12 bp |

Application-Based Performance

The choice of chemistry impacts success in specific research applications.

Table 5: Chemistry Performance by Research Application

| Application | Recommended Chemistry | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [9] | SBS | High throughput and low cost per base make it ideal for large-scale projects. |

| Targeted Gene Panels [9] | SBS | High accuracy for detecting SNVs and small indels in defined regions. |

| De Novo Genome Assembly [12] [9] | Long-Read SBS (e.g., PacBio) | Long reads span repetitive regions and resolve complex structural variations. |

| Epigenetics / Methylation [10] [12] | Long-Read SBS (PacBio) / Nanopore | PacBio detects kinetics changes; Nanopore detects base modifications directly. |

| Metagenomics [9] | Long-Read Sequencing | Long reads improve species classification and resolution of complex microbiomes. |

The Research Reagent Toolkit

Successful execution of sequencing experiments requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The core components are largely consistent across chemistries, though their specific formulations are platform-dependent.

Table 6: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for NGS

| Reagent / Material | Function | Chemistry Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kit [8] | Fragments DNA and ligates platform-specific adapter sequences. | Universal, but adapter sequences are unique to each platform. |

| Flow Cell [10] [8] | Solid surface where clonal amplification and sequencing occur. | Universal, but surface chemistry and architecture differ (e.g., patterned vs. non-patterned). |

| Polymerase Enzyme [9] | Catalyzes DNA strand synthesis during sequencing. | Critical for SBS and SBB; not used in SBL or Nanopore. |

| DNA Ligase Enzyme [8] | Joins DNA fragments during SBL and adapter ligation. | Critical for SBL; also used in library prep for all chemistries. |

| Fluorescent dNTPs / Probes [8] [9] | Labeled nucleotides or probes for optical base detection. | Used in SBS (reversible terminators), SBL (ligation probes), and SBB (binding probes). |

| Unmodified dNTPs [9] | Natural nucleotides for DNA strand extension. | Used in SBB incorporation step and non-optical SBS (Ion Torrent). |

The comparative analysis of Sequencing by Synthesis, Ligation, and Binding reveals a clear landscape: SBS, particularly the reversible terminator chemistry used by Illumina, remains the dominant workhorse for high-throughput, accurate short-read sequencing applicable to most WGS and targeted sequencing studies. SBL offers an alternative pathway with inherent strengths in base encoding but is limited by shorter reads. The emerging SBB chemistry promises high accuracy by separating binding from incorporation. For accuracy research, the selection is not a matter of identifying a single "best" chemistry but of matching the technology's strengths to the genomic target. Critical evaluation of benchmarking data, especially performance in challenging regions often excluded from simplified metrics, is essential for making an informed choice that ensures comprehensive and biologically relevant insights.

In next-generation sequencing (NGS), the quality of the generated data is paramount, as it directly impacts the reliability of downstream biological interpretations. The Q-score (Phred quality score) serves as the fundamental, standardized metric for quantifying sequencing accuracy. This integer value represents the probability that a given base has been called incorrectly by the sequencing instrument. Understanding Q-scores and the distinct error profiles of different sequencing platforms is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the appropriate technology for their specific applications, from variant discovery in oncology to rare disease diagnosis.

The relationship between Q-scores and base-call accuracy is logarithmic. A higher Q-score indicates a lower probability of error. For instance, the widely cited benchmark of Q30 denotes a 1 in 1,000 error probability, or 99.9% base-call accuracy. A growing number of platforms now achieve Q40, which indicates a 1 in 10,000 error probability, or 99.99% accuracy [14]. This tenfold improvement in accuracy is particularly crucial for detecting low-frequency somatic mutations in cancer research and for liquid biopsy applications.

oO0| Sequencing Platform Accuracy & Error Profiles |0Oo

Understanding Q-Scores and Error Profiles

The Fundamentals of Q-Scores

The Phred Q-score is calculated as Q = -10 log₁₀(P), where P is the estimated probability that a base was called incorrectly [15]. This logarithmic scale means that small increases in Q-score represent significant leaps in accuracy. For example, moving from Q30 to Q40 reduces the error rate by a factor of ten, a critical improvement when sequencing millions or billions of bases.

Different sequencing technologies exhibit characteristic error profiles—systematic patterns of mistakes. Short-read technologies, like Illumina's Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), typically demonstrate very low substitution error rates but can struggle in homopolymer regions and repetitive sequences [16]. In contrast, long-read technologies have historically had higher overall error rates, but these are often random and thus correctable through consensus strategies. Oxford Nanopore technologies, for instance, have traditionally shown strengths in detecting base modifications but faced challenges with indels in repetitive regions, though their latest duplex chemistry has substantially improved accuracy [17] [12].

Experimental Benchmarking for Accuracy Assessment

Robust comparison of sequencing platforms requires standardized benchmarking using well-established reference materials and validated bioinformatics pipelines. A common approach involves sequencing the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) reference genomes (e.g., HG002) and comparing variant calls to the high-confidence benchmarks provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [13].

Key metrics in these analyses include:

- False Positive Rate: Incorrectly identified variants.

- False Negative Rate: Missed true variants.

- Coverage Uniformity: Consistency of read depth across regions with varying GC content.

- Variant Calling Accuracy: Separate assessment for SNVs, indels, and SVs.

Experimental designs often involve downsampling sequence data to various coverage depths (e.g., 10× to 120×) to evaluate how efficiently each platform achieves accurate variant calling, which directly impacts project cost-effectiveness [14]. For microbiome studies, the same environmental sample is sequenced across different platforms, and the resulting community profiles are compared to evaluate taxonomic resolution and diversity metrics [18].

Comparative Performance of Sequencing Platforms

Short-Read Sequencing Platforms

Short-read platforms dominate high-throughput applications due to their cost-effectiveness and massive parallelization. However, significant performance differences exist.

Table 1: Accuracy and Performance of Short-Read Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Reported Q-Score | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X [13] | ~Q30 (SBS method) [16] | High uniformity, low substitution errors, comprehensive genome coverage | Struggles with long homopolymers, large structural variants | Large-scale WGS, population studies, transcriptomics |

| Element AVITI [14] | Q40 (with Avidite chemistry); Q50+ (with UltraQ chemistry) | High accuracy for rare variants, lower required coverage | Newer platform with a smaller installed base | Precision oncology, liquid biopsy, rare variant detection |

| MGI DNBSEQ-T1+ [19] | Q40 | Competitive accuracy and throughput | Limited market presence outside China | General-purpose NGS applications requiring high accuracy |

Illumina's platform, when combined with its DRAGEN secondary analysis, demonstrates strong performance across the entire genome, including in challenging GC-rich regions where other technologies like the Ultima Genomics UG 100 show significant coverage drop-offs [13]. A key finding from comparative studies is that platforms with higher raw read accuracy (e.g., Q40) can achieve the same variant calling accuracy as Q30 platforms at substantially lower sequencing coverage (e.g., 66.6% of the coverage), leading to estimated cost savings of 30-50% per sample [14].

Long-Read Sequencing Platforms

Long-read sequencing technologies excel in resolving complex genomic regions and detecting large structural variations.

Table 2: Accuracy and Performance of Long-Read Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Technology | Reported Q-Score | Read Length | Key Error Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio Revio/Vega [17] [12] | HiFi (SMRT) | Q30 - Q40 (HiFi reads) | 10-25 kb | Very low, random errors (<0.1%) |

| Oxford Nanopore [17] [12] | Nanopore (Simplex) | ~Q20 (Simplex, ~99%) | 20 kb -> 4 Mb | Higher indel errors in repeats |

| Oxford Nanopore [12] | Nanopore (Duplex) | >Q30 (Duplex, >99.9%) | Ultra-long | Improved accuracy, lower throughput |

PacBio's HiFi sequencing generates highly accurate long reads by repeatedly sequencing the same circularized DNA molecule to produce a consensus sequence. This method achieves a compelling combination of long read lengths and high base-level accuracy (exceeding 99.9%), making it suitable for applications requiring both attributes, such as de novo genome assembly and phased variant detection [17] [12].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies has dramatically improved its accuracy with the introduction of duplex sequencing, where both strands of a DNA molecule are sequenced. This allows the basecaller to correct random errors, pushing accuracy above Q30 [12]. However, its unique error profile and capacity for ultra-long reads make it ideal for real-time pathogen surveillance and detecting base modifications directly, without bisulfite conversion [17].

oO0| Experimental Benchmarking Workflow |0Oo

Experimental Data and Benchmarking Studies

Whole-Genome Sequencing Benchmark (Illumina vs. Ultima)

An internal comparative analysis by Illumina evaluated its NovaSeq X Series against the Ultima Genomics UG 100 platform for whole-genome sequencing [13]. The study highlighted critical methodological differences: Illumina measured accuracy against the full NIST v4.2.1 benchmark, while Ultima used a defined "high-confidence region" (HCR) that masks 4.2% of the genome, including challenging homopolymers and repetitive sequences.

The results demonstrated that, when assessed against the complete benchmark, the NovaSeq X Series produced 6× fewer SNV errors and 22× fewer indel errors than the UG 100 platform. Furthermore, the NovaSeq X Series maintained high coverage and variant-calling accuracy in repetitive regions and GC-rich sequences, whereas the UG 100 platform exhibited significant coverage drops in mid-to-high GC-rich regions, potentially excluding disease-associated genes like B3GALT6 and FMR1 from reliable analysis [13].

The Impact of Q40 on Rare Variant Detection (Element AVITI)

A preprint study from Fudan University provided a comprehensive evaluation of Q40 sequencing using the Element AVITI system [14]. Researchers performed germline and somatic variant calling on reference standards, comparing AVITI's Q40 data to Illumina Q30 data. The key finding was that AVITI Q40 data achieved equivalent accuracy to Illumina Q30 data at only 66.6% of the relative coverage.

This enhanced efficiency translates directly into cost savings of 30-50% per sample, as less sequencing depth is required to achieve the same analytical precision. For somatic variant detection, the study found that Q40 accuracy provided superior detection of low-frequency mutations, a critical advantage for oncology applications like liquid biopsy and minimal residual disease monitoring, where sensitivity to rare variants is paramount [14].

Microbiome Profiling Comparison (PacBio, ONT, Illumina)

A 2025 study compared 16S rRNA gene sequencing across Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore Technologies for soil microbiome analysis [18]. After normalizing sequencing depth, the study found that ONT and PacBio provided comparable assessments of bacterial diversity, with PacBio showing a slight advantage in detecting low-abundance taxa. Despite ONT's inherently higher sequencing error rate, its errors did not significantly distort the interpretation of well-represented microbial taxa, and all technologies enabled clear clustering of samples by soil type.

This demonstrates that for applications like microbiome profiling, where the goal is community-level analysis rather than single-base precision, the longer read lengths providing superior taxonomic resolution can outweigh the importance of raw base-level accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sequencing Benchmarking

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| NIST RM 8398 (DNA) [14] | Reference material for germline variant calling | Benchmarking SNV/InDel accuracy in human genomes |

| HCC1295/BL Mixed Cell Line [14] | Reference for somatic variant detection | Evaluating sensitivity for low-frequency tumor variants |

| Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microprep Kit [18] | DNA extraction from complex samples | Standardizing input DNA for microbiome studies |

| ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbiome Standard [18] | Defined microbial community control | Assessing taxonomic classification accuracy |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 [18] | Library preparation for PacBio HiFi sequencing | Generating long-read libraries from dsDNA |

| Native Barcoding Kit 96 [18] | Multiplexed library prep for ONT | Preparing 96 samples for simultaneous sequencing on MinION/PromethION |

| NovaSeq X Series 10B Reagent Kit [13] | High-throughput sequencing on Illumina | Producing ~35x WGS data on NovaSeq X Plus |

The choice of a sequencing platform involves a careful balance of accuracy, cost, throughput, and application-specific needs. Q-scores provide a crucial universal metric for comparing base-calling accuracy, but the complete picture requires an understanding of platform-specific error profiles. Short-read platforms from Illumina and Element Biosciences offer very high accuracy (Q30-Q40+) and are well-suited for large-scale variant discovery projects. In contrast, long-read platforms from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore provide unparalleled resolution in complex genomic regions, with PacBio's HiFi reads offering a unique combination of length and high accuracy.

For precision oncology and rare variant detection, the leap from Q30 to Q40+ accuracy can significantly reduce the sequencing depth required, thereby lowering costs and improving sensitivity [14]. For clinical genetics, comprehensive coverage of the entire genome, including challenging regions often masked by some platforms, is essential to avoid missing pathogenic variants [13]. In microbiome and metagenomic studies, the taxonomic resolution offered by long reads can be more impactful than raw base-level accuracy [18].

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, the benchmarks for accuracy will become even more stringent. Emerging chemistries promising Q50 and beyond, along with novel approaches like Roche's SBX technology, will further push the boundaries of what is detectable. Researchers must therefore stay informed through independent, rigorous benchmarking studies to make optimal platform selections that ensure the biological validity and reproducibility of their findings.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized genomic research, yet each platform introduces distinct artifacts that can impact data interpretation. Understanding these technology-specific error patterns is crucial for selecting the appropriate sequencing platform and designing robust bioinformatics pipelines. Among the most well-documented inherent error patterns are the substitution errors predominant in Illumina sequencing data and the insertion-deletion (indel) errors within homopolymer regions characteristic of Ion Torrent technology. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these error profiles, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies from controlled studies, to inform researchers and sequencing professionals in their platform selection and data analysis strategies.

The fundamental differences in detection chemistry between Illumina and Ion Torrent sequencing platforms are the root cause of their distinct error profiles.

Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis technology utilizes fluorescently labeled, reversible-terminator nucleotides. During each cycle, a single nucleotide is incorporated, its fluorescent signal is detected, and the terminator is chemically cleaved to allow the next incorporation. This step-wise process is highly accurate for determining base identity but is susceptible to phasing and fading effects that can lead to substitution errors, particularly in later cycles [20] [21].

In contrast, Ion Torrent's semiconductor sequencing detects the hydrogen ions (pH change) released during nucleotide incorporation. Nucleotides flow sequentially over the DNA templates. If a nucleotide is complementary to the template, it is incorporated, releasing a number of protons proportional to the number of bases added. A key distinction is that multiple identical nucleotides in a homopolymer tract can be incorporated in a single flow. The challenge lies in accurately estimating the number of incorporations from the analog pH signal, which becomes increasingly difficult as homopolymer length increases, leading to indel errors [20] [22] [23].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Illumina and Ion Torrent Sequencing Technologies

| Feature | Illumina | Ion Torrent |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Fluorescent signal from reversible terminators | pH change (ion release) from polymerization |

| Nucleotide Incorporation | Single base per cycle | Multiple identical bases possible per flow |

| Primary Error Mode | Substitutions | Insertions/Deletions (Indels) |

| Primary Error Context | Specific sequence motifs (e.g., GGC), post-homopolymer bases | Homopolymer regions |

| Typical Workflow | Bridge amplification on flowcell | Emulsion PCR on beads |

Experimental Data and Quantitative Comparison

Controlled studies using microbial genomes and mock communities have quantitatively characterized the error profiles of both platforms.

Error Rates and Types

A foundational study comparing three NGS platforms sequenced a set of four microbial genomes with varying GC content. The analysis revealed that while both platforms produced usable sequence, their error patterns were distinct. The study found that variant calling from Ion Torrent data could yield a slightly higher number of variants but at the expense of a significantly higher false positive rate compared to Illumina's MiSeq [20].

A focused comparison of the platforms for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing further highlighted these differences. The Ion Torrent PGM demonstrated higher overall error rates and a specific pattern of premature sequence truncation that was dependent on both sequencing direction and the target species. This led to organism-specific biases in resulting community profiles. A key finding was that the majority of errors on the Ion Torrent platform were indels, while Illumina errors were predominantly substitutions [21].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Error Profiles from Experimental Studies

| Parameter | Illumina | Ion Torrent | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Indel Error Rate | Low | ~2.84% (OneTouch 200 bp kit) [22] | Re-sequencing of bacterial genomes |

| Indel Error Rate (after QC) | Low | ~1.38% (OneTouch 200 bp kit) [22] | Re-sequencing of bacterial genomes |

| Primary Error Type | Substitutions | Insertions/Deletions (Indels) [20] [21] | Microbial genome & 16S rRNA sequencing |

| Homopolymer Error Source | Incorrect base call after a run [24] | Inaccurate length calling within a run [22] [23] | Controlled experiments & E. coli re-sequencing |

| GC-rich Genome Bias | Near-perfect coverage on GC-rich, neutral, and moderately AT-rich genomes [20] | Profound bias and ~30% no-coverage in extremely AT-rich genomes [20] | Sequencing of Plasmodium falciparum (19.3% GC) |

Context-Specific Errors

The errors for both platforms are not random but occur in specific sequence contexts.

For Ion Torrent, the dominant issue is homopolymer length. Inaccurate "flow-calls" typically result in the over-calling of short homopolymers and under-calling of long homopolymers [22] [23]. This is a direct consequence of the non-linear pH response when multiple identical bases are incorporated simultaneously. Furthermore, flow-call accuracy decreases with consecutive flow cycles [22].

For Illumina, a significant source of substitution errors occurs immediately after homopolymer runs. An application note from Ion Torrent highlighted that in an E. coli dataset, approximately half of all base substitution errors were attributable to miscalling the base following a homopolymer, with the effect being strand-specific [24]. Other studies have identified specific GC-rich motifs like GGT and GGC as having increased substitution error frequencies [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the data, here are the methodologies from key studies cited in this guide.

- Library Preparation: Platform-specific libraries were constructed for four microbial genomes: Bordetella pertussis (67.7% GC), Salmonella Pullorum (52% GC), Staphylococcus aureus (33% GC), and Plasmodium falciparum (19.3% GC).

- Illumina Sequencing: PCR-free libraries were uniquely barcoded, pooled, and run on both an Illumina MiSeq (paired-end 150-bp reads) and an Illumina HiSeq (paired-end 75-bp reads).

- Ion Torrent Sequencing: Libraries were run on a single Ion 316 chip for 65 cycles.

- Pacific Biosciences Sequencing: Standard libraries with ~2 kb inserts were run on multiple SMRT cells to provide coverage.

- Data Analysis: All sequence datasets were randomly down-sampled to a 15x average genome coverage for a fair comparison. Reads were mapped to the corresponding reference genome, and coverage distribution, GC bias, and variant calling were analyzed.

- Sample Types: A 20-organism mock bacterial community (BEI Resources) and a collection of primary human specimens.

- Library Preparation: 16S rRNA V1-V2 regions were amplified using primers incorporating Illumina- or Ion Torrent-compatible adapters. For Ion Torrent, DNA was amplified in two separate reactions to enable bidirectional sequencing of the amplicon.

- Sequencing:

- Illumina: Performed on a MiSeq platform with a 500-cycle kit, using custom primers and spiked-in PhiX control.

- Ion Torrent: Templating and enrichment were performed with the OneTouch 2 system. Sequencing was on an Ion PGM using 400-bp sequencing kits with both default and an alternative flow order.

- Data Processing: Ion Torrent reads were subjected to run-length encoding to optimize alignment in homopolymer regions. Primer sequences were trimmed, and reads were classified to specific taxa.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential reagents and their functions as identified in the experimental studies cited in this guide. The choice of enzyme, in particular, can significantly impact error rates and bias.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials from Featured Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Significance in Error Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Kapa HiFi Polymerase | A high-fidelity DNA polymerase used for library amplification. | Substituting the standard Platinum Taq with Kapa HiFi during Ion Torrent library prep profoundly reduced the extreme coverage bias observed with the AT-rich P. falciparum genome [20]. |

| Ion Xpress Fragment Library Kit | An Ion Torrent kit featuring an enzymatic "Fragmentase" for DNA shearing. | Streamlines library preparation by avoiding physical shearing. Found to provide equal genomic representation compared to physical shearing methods [20]. |

| Ion Xpress Barcodes | 10- to 12-bp sequences optimized for the Ion Torrent platform. | Used for sample multiplexing. These barcodes are optimized for maximal error correction, average sequence content, and the specific nucleotide flow order of the platform [21]. |

| PhiX Control Library | A known, small viral genome used as a sequencing control. | Spiked into Illumina runs (often at 1%) to allow proper focusing, matrix calculation, and calibration of base calling, thereby improving overall run accuracy [21] [26]. |

| Alternative Flow Order | A modified sequence of nucleotide flows for Ion Torrent. | More aggressive phase correction can improve sequencing of difficult templates (e.g., with biased base usage) compared to the default flow order, though it may be less efficient at overall extension [21]. |

Analysis and Mitigation Strategies

Understanding these error patterns enables researchers to develop strategies to mitigate their impact.

For Ion Torrent data, the homopolymer issue is systematic. bioinformatics approaches that model the flowgram values and incorporate knowledge of the sequencing process, such as the state machine model proposed by Golan and Medvedev, can significantly improve read error rates by better interpreting ambiguous flow signals [27]. For applications like 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, employing bidirectional amplicon sequencing and optimized flow orders can minimize artifacts and organism-specific biases [21].

For Illumina data, quality filtering is essential to reduce downstream artifacts. This can lower error rates significantly, albeit at the expense of discarding some alignable bases [26]. The strand-specificity of the post-homopolymer error can be used as a criterion to distinguish true low-abundance polymorphisms from sequencing errors, as errors will appear predominantly in reads sequenced from one direction [24]. Furthermore, error correction tools like BrownieCorrector have been developed specifically to address errors in reads overlapping highly repetitive DNA regions, including homopolymers, which can improve de novo genome assembly results [28].

The choice between Illumina and Ion Torrent sequencing platforms involves a direct trade-off between their inherent error patterns. Illumina platforms, with their lower overall error rate and predisposition toward substitution errors, are often preferred for applications requiring high single-base accuracy, such as single-nucleotide variant (SNV) discovery and quantitative genotyping. Conversely, Ion Torrent platforms, with their higher indel rates in homopolymer regions, require careful consideration for applications like amplicon sequencing or variant calling in repetitive genomic regions. A comprehensive understanding of these biases, coupled with the implementation of appropriate experimental and bioinformatics mitigation strategies, is fundamental to generating robust and reliable genomic data. The comparative data and methodologies outlined in this guide provide a framework for researchers to make informed decisions.

Third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies, characterized by their ability to sequence single DNA or RNA molecules and generate long reads spanning thousands to tens of thousands of bases, have fundamentally transformed genomic research. Unlike second-generation short-read technologies that require DNA fragmentation and PCR amplification, TGS platforms analyze native nucleic acids, preserving epigenetic information and enabling the resolution of complex genomic regions. As of 2025, the landscape is dominated by two principal technologies: Pacific Biosciences' (PacBio) Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technologies' (ONT) nanopore sequencing [12] [10]. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal platform for accuracy-focused research.

The two leading TGS technologies operate on fundamentally different physical principles to achieve long-read sequencing.

PacBio SMRT Sequencing utilizes an optical detection system. DNA polymerase enzymes are anchored at the bottom of tiny wells called zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs). As the polymerase incorporates fluorescently-labeled nucleotides into the growing DNA strand, each base addition emits a flash of light characteristic of the base type, which is detected in real-time [12] [17]. Its hallmark HiFi (High-Fidelity) mode circularizes DNA fragments, allowing the polymerase to read the same molecule multiple times (typically 10-20 passes) to generate a highly accurate circular consensus sequence (CCS) with reported accuracy exceeding 99.9% [12] [17].

Oxford Nanopore Sequencing employs an electrical detection system. A single strand of DNA is threaded through a biological protein nanopore embedded in a membrane. An applied voltage drives an ionic current through the pore, and as different nucleotides pass through, they cause characteristic disruptions in the current. These signal changes are interpreted by sophisticated basecalling algorithms to determine the DNA sequence [17]. A significant advancement is duplex sequencing, where both strands of a DNA molecule are sequenced, pushing accuracy to over Q30 (>99.9%) and rivaling short-read platforms [12].

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflows of these two technologies.

Performance Comparison: A Data-Driven Analysis

A multi-dimensional comparison of key performance metrics is essential for platform selection. The following table synthesizes data from recent instrument specifications and benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Leading TGS Platforms

| Feature | PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | Optical (SMRT) | Electrical (Nanopore) |

| Typical Read Length | 500 bp - 20+ kb [17] | 20 kb - >4 Mb (Ultra-long) [17] |

| Single-Read Accuracy | Q33 (99.95%) [17] | ~Q20 (99%) to Q30+ (>99.9% with duplex) [12] [17] |

| Typical Run Time | ~24 hours [17] | ~72 hours [17] |

| DNA Modification Detection | 5mC, 6mA (native) [29] [17] | 5mC, 5hmC, 6mA (native) [17] |

| Variant Calling (Indels) | Yes (Strong in homopolymers) [17] | Limited (Challenged in homopolymers) [17] |

| Data Output per Flow Cell/Chip | 60-120 Gb [17] | 50-100 Gb [17] |

| Raw Data File Size | ~30-60 GB (BAM) [17] | ~1300 GB (FAST5/POD5) [17] |

Experimental Evidence in Application

Recent independent studies highlight the performance characteristics of these platforms in real-world research scenarios:

Bacterial Epigenetics (6mA Detection): A 2025 comprehensive comparison evaluated eight tools for profiling bacterial DNA N6-methyladenine (6mA) using Nanopore (R9/R10) and SMRT sequencing. The study found that while most tools could identify methylation motifs, their performance at single-base resolution varied significantly. SMRT sequencing and the Dorado basecaller for Nanopore consistently delivered strong performance. The study also noted that existing tools, regardless of the platform, struggle to accurately detect low-abundance methylation sites [29] [30].

Microbial Pathogen Epidemiology: A 2025 benchmark study compared Illumina short-reads and ONT long-reads for genome assembly and variant calling of phytopathogenic bacteria. It concluded that assemblies from long reads were more complete than those from short-read data. For variant calling, an optimized approach where long reads were computationally fragmented before analysis with short-read pipelines proved most accurate. This demonstrates that ONT data, with appropriate processing, is of sufficient quality for epidemiological studies [31].

SARS-CoV-2 Genotyping: A study published in 2025 evaluated PacBio SMRT sequencing for typing SARS-CoV-2. On 1,646 clinical samples, SMRT sequencing demonstrated 83.6% sensitivity, which was correlated with viral load. While its overall sensitivity was lower than Illumina short-read sequencing (90.8%), SMRT was more efficient at identifying the two lineages in a co-infection case due to its ability to amplify long fragments. Consensus sequences from both methods were highly similar, with a maximum of 4 nucleotide differences, confirming both provide accurate typing [32].

Human Cancer Genomics: Research published in 2025 used ONT R10.4.1 long-read sequencing to investigate high-grade serous ovarian cancer. The technology successfully uncovered novel genomic and epigenomic alterations in repetitive regions like centromeres and transposable elements, which are largely inaccessible to short-read sequencing. This included the discovery of centromeric hypomethylation patterns that distinguished tumors with homologous recombination deficiency [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental design for third-generation sequencing requires specific reagents and materials to ensure high-quality results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Third-Generation Sequencing

| Item | Function | Considerations for Platform Choice |

|---|---|---|

| High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate long, intact DNA strands preserving native modifications. | Critical for both platforms; input DNA quality directly influences read length. |

| Methylation Control DNA (e.g., from defined bacteria strains) | To benchmark and validate the detection of epigenetic marks like 6mA and 5mC. | Essential for epigenetic studies; both platforms detect modifications natively [29]. |

| SMRTbell Adapters (PacBio) | Hairpin adapters to create circular templates for HiFi CCS sequencing. | Specific to PacBio's HiFi mode, enabling multiple passes of the same molecule [17]. |

| Native Barcoding Kit (ONT) | To tag samples uniquely for multiplexing before library preparation. | Preserves native DNA and allows for direct methylation detection. |

| Flow Cell (R10.4.1 for ONT; SMRT Cell for PacBio) | The consumable containing nanopores or ZMWs where sequencing occurs. | ONT's R10.4.1 offers improved accuracy over previous versions [29]. |

| Basecalling & Analysis Software (e.g., Dorado for ONT) | Converts raw signals (current/light) into nucleotide sequences. | Choice of model balances accuracy, speed, and sensitivity to modifications [29] [17]. |

Experimental Workflow for a Comparative Study

A robust protocol for comparing sequencing platform performance, particularly for accuracy in variant and modification detection, is outlined below. This methodology is adapted from recent benchmarking publications [29] [31].

1. Sample Selection and Preparation:

- Biological Material: Select a well-characterized sample with a known truth set. Common choices include a bacterial strain with a defined methylation system (e.g., Pseudomonas syringae with a known 6mA MTase) [29] or a human reference cell line (e.g., HG002 for the Genome in a Bottle consortium).

- DNA Extraction: Perform High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA extraction using a kit designed for long-read sequencing to maximize read length and integrity.

- Control Groups: Include a modification-deficient control. For bacterial epigenetics, this could be a ΔMTase knockout strain [29]. For human genomics, whole-genome amplified (WGA) DNA can serve as a non-methylated control.

2. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- PacBio HiFi Library: Use the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit. This involves DNA shearing, end-repair, A-tailing, and ligation of SMRTbell adapters to create circularizable templates. Sequence on a Revio or Sequel IIe system to generate HiFi reads [17] [32].

- ONT Library: Use the Ligation Sequencing Kit with native barcoding. This involves DNA repair, dA-tailing, and ligation of sequencing adapters. Sequence on a PromethION platform with R10.4.1 flow cells. For maximum accuracy, consider using the Q20+ duplex chemistry [12] [33].

- Cross-Platform Validation: Sequence the same sample using a gold-standard method for validation, such as SMRT sequencing for methylation or Illumina short-reads for small variants, if applicable [29] [32].

3. Data Processing and Analysis:

- Basecalling: For ONT data, use the latest basecaller (e.g., Dorado) with a model that includes modification calling. PacBio HiFi reads are basecalled directly on the instrument [29] [17].

- Alignment: Map reads from both platforms to the reference genome using aligners like minimap2 [33].

- Variant/Modification Calling:

- For PacBio: Use platform-specific tools or integrated pipelines for variant and modification calling.

- For ONT: Apply specialized tools for bacterial 6mA detection (e.g., Dorado, Nanodisco, mCaller) and compare their performance against the known ground truth [29].

- Performance Metrics: Calculate sensitivity, precision, and F1-score at the single-base level for variant and modification calls. For assembly, assess contiguity (N50) and completeness [31].

The following diagram visualizes this comparative experimental workflow.

Both PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore TGS technologies offer powerful capabilities that overcome the limitations of short-read sequencing. The choice between them is not a matter of absolute superiority but depends on the specific research goals.

PacBio HiFi sequencing is the leading choice for applications demanding the highest single-read accuracy, such as small variant discovery (SNVs and indels) in complex regions, haplotyping, and building high-quality reference genomes. Its consistent >99.9% accuracy provides high confidence for clinical and diagnostic research [17].

Oxford Nanopore sequencing offers unparalleled advantages in read length, portability, and real-time data streamings. Its ability to directly detect a broad range of epigenetic marks and its lower instrument cost make it ideal for metagenomics, assembly of highly repetitive genomes, rapid pathogen surveillance in the field, and comprehensive epigenomic profiling [12] [33].

For researchers focused on accuracy, the decision hinges on the required context: PacBio delivers base-level precision out-of-the-box, while Nanopore, especially with duplex sequencing and advanced bioinformatics, provides a flexible and powerful platform for exploring previously intractable regions of the genome. As both technologies continue to evolve, their complementary strengths will further empower scientists to unravel the complexities of genomics and epigenomics.

Matching Platform to Purpose: Accuracy-Driven Applications in Research and Diagnostics

High-throughput population studies represent a cornerstone of modern genomics, enabling the discovery of genetic variants associated with diseases, evolutionary history, and population structure. The successful execution of these studies hinges on a critical balance between sequencing scale and base-calling accuracy. Short-read sequencing technologies, dominated by sequencing-by-synthesis platforms, have emerged as the primary engine for these initiatives due to their unparalleled throughput and cost-effectiveness. These technologies enable the processing of thousands of samples simultaneously, generating terabytes of data per instrument run [34] [35]. However, this massive scale must be reconciled with stringent accuracy requirements for reliable variant discovery, particularly for detecting low-frequency alleles that may have significant biological implications [36]. This comparative analysis examines the performance characteristics of short-read sequencing platforms in the context of high-throughput population studies, evaluating their capabilities against emerging long-read technologies and providing a framework for platform selection based on specific research objectives.

The fundamental challenge in population genomics lies in distinguishing true biological variation from sequencing artifacts, a task complicated by the inherent error profiles of different sequencing chemistries. While short-read platforms achieve impressive aggregate accuracy, their error rates are not uniformly distributed across the genome, with specific sequence contexts such as homopolymer regions presenting particular challenges [20] [35]. Understanding these platform-specific characteristics is essential for designing robust population studies and accurately interpreting resulting data. Furthermore, the continuous innovation in sequencing technologies has blurred the historical distinction between short- and long-read platforms, with newer synthetic long-read approaches bridging the gap between these modalities [12]. This guide provides an objective comparison of current sequencing platforms through the lens of population study requirements, focusing on the critical metrics of accuracy, throughput, cost, and applicability to large-scale genetic analysis.

The current sequencing ecosystem encompasses multiple technology generations, each with distinct operational principles and performance characteristics. Second-generation or short-read platforms utilize sequencing-by-synthesis approaches that generate massive volumes of data through parallel processing of clonally amplified DNA fragments. These systems form the workhorse for most high-throughput population studies due to their maturity, established analytical pipelines, and continually reducing costs [37] [35]. Third-generation or long-read technologies sequence single DNA molecules in real time, producing significantly longer reads that are particularly valuable for resolving complex genomic regions and structural variations [12]. A more recent development includes synthetic long-read technologies that combine short-read accuracy with enhanced phasing capabilities through specialized library preparation methods.

Table 1: Sequencing Platform Classification and Key Characteristics

| Platform Category | Technology Examples | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations | Primary Population Study Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read Sequencing | Illumina NovaSeq, HiSeq, MiSeq | High throughput, low cost per base, established analytical methods | Limited read length, amplification bias, GC-coverage bias | Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), population variant cataloging, large-scale resequencing |

| Long-Read Sequencing | PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore | Resolves complex regions, detects structural variants, direct methylation detection | Higher cost per base, lower throughput for some applications, specialized infrastructure requirements | Reference genome improvement, structural variant discovery, haplotype phasing in populations |

| Emerging/Hybrid Approaches | Illumina Complete Long Reads, PacBio Revio | Combination of accuracy and long-range information, improving cost-effectiveness | Evolving analytical methods, intermediate cost structure | Population-scale de novo assembly, comprehensive variant discovery |

For high-throughput population studies, short-read platforms currently dominate due to their ability to generate consistent, accurate data across thousands of samples at a manageable cost. The Illumina ecosystem, in particular, has established itself as the industry standard, with platforms ranging from the benchtop MiSeq to the production-scale NovaSeq X series capable of outputting up to 16 terabases per run [12]. This massive throughput enables population studies at unprecedented scale, with projects now routinely sequencing tens to hundreds of thousands of individuals. The key technological differentiators between platforms include read length (typically 50-300 base pairs for short-read systems), accuracy profiles, throughput per run, and cost per gigabase [35]. Understanding these specifications is crucial for matching platform capabilities to the specific requirements of a population study.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Accuracy, Throughput and Cost

Direct comparison of sequencing platforms requires examination of multiple quantitative metrics that collectively determine their suitability for population studies. Accuracy, typically expressed as Phred-scaled quality scores (Q-scores), represents the probability of an incorrect base call and is fundamental for reliable variant detection [5]. Throughput, measured in gigabases (Gb) or terabases (Tb) per run, determines the scaling potential for large studies. Cost per gigabase directly impacts study design and sample size, with both instrument and consumable expenses contributing to the total expenditure.

Table 2: Sequencing Platform Performance Metrics Comparison

| Platform/Technology | Typical Read Length | Raw Accuracy (Q-score) | Maximum Output per Run | Estimated Cost per Gb* | Variant Calling Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | 2x150 bp | ≥Q30 (99.9%) | 16 Tb | $0.07-$0.15 | SNVs, small indels, common structural variants |

| Illumina HiSeq 3000/4000 | 2x150 bp | ≥Q30 (99.9%) | 1.5 Tb | $0.10-$0.20 | SNVs, small indels, population frequency analysis |

| Illumina MiSeq | 2x300 bp | ≥Q30 (99.9%) | 15 Gb | $0.50-$1.00 | Targeted regions, validation studies, method development |

| PacBio HiFi | 10-25 kb | ≥Q30 (99.9%) | 360 Gb (Revio) | $5-$15 | Structural variants, complex regions, haplotype phasing |

| Oxford Nanopore (duplex) | 10-100+ kb | ≥Q30 (99.9%) | 100-200 Gb (PromethION) | $5-$20 | Structural variants, epigenomic modifications, rapid screening |

*Cost estimates vary based on institutional agreements, utilization rates, and ancillary expenses. Values represent approximate range for reagents and consumables.

The data reveals a clear distinction between platform classes. Short-read technologies provide superior throughput and cost-efficiency for base-level variant discovery, while long-read platforms excel in resolving complex genomic regions despite higher costs. For population studies focused on single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) at population scale, short-read platforms offer an optimal balance of accuracy and throughput. The consistency of Illumina's Q30+ scores across platforms ensures high base-calling accuracy, with error rates below 0.1% [5]. This level of accuracy is particularly important for population studies where false positive variant calls can lead to incorrect associations, while false negatives can cause researchers to miss biologically significant findings.

The throughput advantage of short-read platforms becomes particularly evident when considering population-scale projects. The latest short-read instruments can sequence hundreds of human genomes at >30x coverage in a single run, dramatically reducing per-sample costs and processing time [34] [12]. This scaling capability has been a critical enabler for initiatives like the UK Biobank, All of Us, and other large biobanks that aim to sequence hundreds of thousands of participants. While long-read technologies have made significant progress in both accuracy and throughput, their current cost structure and operational requirements still present challenges for the largest population studies, though they play an increasingly important role in complementary applications such as reference genome improvement and complex variant validation.

Experimental Benchmarking: Methodologies for Platform Assessment

Rigorous benchmarking of sequencing platform performance requires standardized experimental designs that eliminate confounding variables while capturing metrics relevant to population studies. Optimal benchmarking methodologies utilize well-characterized reference samples, standardized library preparation protocols, and orthogonal validation to establish ground truth for performance assessment. The increasing complexity of sequencing technologies demands more sophisticated evaluation frameworks that go beyond simple accuracy metrics to include factors such as reproducibility, GC-bias, and variant detection performance across different genomic contexts.

Reference Materials and Study Design

Comprehensive platform comparisons typically employ reference materials with established "ground truth" genotypes, such as the Genome in a Bottle Consortium samples (e.g., NA12878) or commercially available multiplex reference standards [20]. These materials enable precise measurement of platform-specific error rates and bias. For population study applications, benchmarking should include diverse samples representing different ancestral backgrounds to identify potential platform-specific biases that might affect variant discovery across populations. Experimental design must control for potential batch effects by processing all samples through identical library preparation, sequencing, and analysis workflows wherever possible. The use of technical replicates across sequencing runs provides essential data on platform reproducibility, a critical factor for studies conducted over extended periods or across multiple sequencing centers.

Analysis Pipelines and Performance Metrics

Standardized bioinformatic processing is essential for meaningful platform comparisons. The benchmarking workflow typically includes raw data quality assessment, adapter trimming, alignment to reference genomes, duplicate marking, base quality recalibration, and variant calling using standardized parameters. Key performance metrics include:

- Base-level accuracy: Measured as Q-scores against known reference bases [5]

- Variant detection sensitivity and precision: For SNVs and indels across different frequency spectra

- Coverage uniformity: Across genomic regions with varying GC content and other challenging contexts

- Allele-specific bias: Particularly important for heterozygous variant detection

- Reproducibility: Concordance between technical replicates processed independently through the entire workflow

Different sequencing chemistries demonstrate distinctive error profiles that must be considered in analysis. Short-read technologies typically exhibit substitution errors that vary by specific sequence context, while early long-read technologies showed higher rates of insertion-deletion errors, particularly in homopolymer regions [20] [35]. These platform-specific error patterns directly impact the optimal choice of variant calling algorithms and filtering strategies for population studies.

Figure 1: Experimental Benchmarking Workflow for Sequencing Platform Comparison

Comparative Analysis in Practice: Key Benchmarking Studies

Recent comprehensive benchmarking studies provide critical empirical data on the performance of contemporary sequencing platforms in realistic research scenarios. These studies highlight the continuing evolution of sequencing technologies and their implications for population genomics. A 2025 benchmarking of imaging spatial transcriptomics platforms on FFPE tissues compared three commercial platforms—10X Xenium, Vizgen MERSCOPE, and Nanostring CosMx—across multiple tissue types [38]. While focused on spatial applications, this study demonstrated important differences in sensitivity and specificity between platforms that parallel findings from DNA sequencing comparisons. The research found that Xenium consistently generated higher transcript counts per gene without sacrificing specificity, and both Xenium and CosMx showed strong concordance with orthogonal single-cell transcriptomics methods [38].

For DNA sequencing specifically, studies comparing short-read and long-read technologies for microbial community profiling provide insights into platform performance in complex mixtures of genomes—a scenario analogous to certain population study designs. A 2025 comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequencing using Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore technologies found that despite differences in sequencing accuracy, both long-read platforms produced comparable assessments of bacterial diversity, with PacBio showing slightly higher efficiency in detecting low-abundance taxa [18]. This finding has significant implications for population studies focusing on microbiomes or other complex cellular mixtures.

Historical comparisons remain informative for understanding the fundamental tradeoffs in sequencing technologies. A seminal 2012 comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences, and Illumina MiSeq sequencers revealed profound platform-specific biases, such as Ion Torrent's severe coverage dropouts in extremely AT-rich regions of the Plasmodium falciparum genome [20]. While specific technologies have evolved, these findings underscore the importance of understanding platform-specific limitations when designing population studies, particularly for genomes with extreme composition or complex architecture. More recent evaluations confirm that short-read technologies continue to demonstrate coverage bias in high-GC and repetitive regions, though improved library preparation methods have mitigated these effects to some extent [20] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Successful execution of high-throughput population studies requires careful selection of reagents and supporting technologies that ensure data quality and reproducibility. The following table outlines key solutions and their applications in sequencing-based population studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Population Sequencing Studies

| Reagent/Technology Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations for Population Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Kapa HyperPrep | Fragment DNA, add platform-specific adapters | Throughput, automation compatibility, hands-on time, bias introduction |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Illumina Exome Panel, IDT xGen Panels | Select genomic regions of interest | Capture efficiency, uniformity, off-target rate, compatibility with population samples |

| Quality Control Tools | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Qubit Fluorometer | Quantify and qualify nucleic acids | Accuracy, sensitivity, throughput, impact on library complexity estimation |

| Reference Standards | Genome in a Bottle, Seracare Reference Materials | Platform calibration and QC | Availability for diverse populations, comprehensive characterization |

| Automation Platforms | Hamilton STAR, Tecan Freedom EVO | Standardize liquid handling | Throughput, cross-contamination prevention, walk-away time |

| Unique Dual Indexes | Illumina IDT UDIs | Sample multiplexing and demultiplexing | Index hopping rate, complexity, cost per sample |

The selection of appropriate library preparation methods is particularly critical for population studies, as different approaches can introduce specific biases that affect variant discovery. PCR-free library preparation methods significantly reduce coverage bias in GC-rich regions compared to traditional PCR-based approaches [20]. For whole-genome sequencing studies, PCR-free protocols are increasingly considered the gold standard, though their higher DNA input requirements may present challenges for certain sample types. For whole-exome or targeted sequencing, capture efficiency and uniformity directly impact the power to detect variants across the targeted regions, with newer hybridization-based methods showing improved performance over earlier amplification-based approaches.

Quality control represents another essential component of the population genomics toolkit. Accurate quantification of input DNA ensures optimal library complexity, preventing batch effects that can arise from varying sample quality across large studies. The integration of unique dual indexes (UDIs) has become particularly important for large-scale multiplexing, as these molecular barcodes enable precise sample identification while minimizing index hopping artifacts that can compromise data integrity in high-throughput sequencing runs. These technical considerations, while sometimes overlooked in study design, fundamentally impact data quality and subsequent biological interpretations in population genomics.

The comparative analysis of sequencing platforms reveals a nuanced landscape for high-throughput population studies. Short-read sequencing technologies, particularly the Illumina ecosystem, maintain a dominant position for large-scale variant discovery due to their unparalleled combination of accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness. The established analytical pipelines and continuous improvements in data quality make these platforms particularly suitable for genome-wide association studies and population variant cataloging involving thousands of samples. The Q30+ base-calling accuracy provides sufficient confidence for single nucleotide variant discovery, while the massive throughput of contemporary instruments enables studies at unprecedented scale [34] [5].

Long-read technologies have evolved from niche applications to viable options for specific population genomics applications, particularly when resolving structural variations or complex genomic regions is a primary objective. The convergence of accuracy between short-read and long-read platforms, with both now achieving Q30+ scores, has narrowed the performance gap for basic variant discovery [12]. However, significant differences remain in cost structure and operational requirements that continue to favor short-read technologies for the largest population studies. Emerging hybrid approaches that combine short-read data with long-range information show particular promise for comprehensive variant discovery across all classes of genetic variation.