Preserving Biomolecular Integrity: Advanced Methods for Long-Term RNA and Extracellular Vesicle Storage

This comprehensive guide details evidence-based protocols for preserving the structural and functional integrity of RNA and extracellular vesicles (EVs) during long-term storage.

Preserving Biomolecular Integrity: Advanced Methods for Long-Term RNA and Extracellular Vesicle Storage

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details evidence-based protocols for preserving the structural and functional integrity of RNA and extracellular vesicles (EVs) during long-term storage. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles of biomolecular degradation, step-by-step methodological applications for diverse sample types, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this article provides a critical resource for ensuring sample quality, enhancing experimental reproducibility, and supporting reliable diagnostic and therapeutic applications in biomedical research.

Understanding the Enemies of Stability: Why RNA and EVs Degrade

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What makes RNA inherently less stable than DNA? The primary reason for RNA's inherent instability compared to DNA is the presence of a reactive 2'-hydroxyl (2'-OH) group on the ribose sugar. This group can act as a nucleophile, attacking the adjacent phosphodiester bond, especially under alkaline conditions, leading to strand cleavage. This process is known as in-line hydrolysis. In contrast, DNA lacks this 2'-OH group, making its phosphodiester bonds significantly more stable—approximately 200 times more stable under neutral pH and physiological magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) concentrations [1].

FAQ 2: Besides its structure, what are the key enemies of RNA in the lab? RNA faces two major categories of threats:

- Ribonucleases (RNases): These enzymes specifically catalyze the degradation of RNA. They are ubiquitous in the environment, found on skin, in dust, and on lab surfaces, and are notoriously stable and difficult to inactivate [2] [3].

- Chemical Hydrolysis: This non-enzymatic process is accelerated by factors such as alkaline pH, high temperatures, and the presence of divalent cations like Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺. These cations can catalyze strand scission when RNA is heated above 80°C [1] [2] [4].

FAQ 3: What is the single most important practice for protecting my RNA samples? The most critical practice is maintaining an RNase-free environment. This involves wearing gloves, using dedicated RNase-free reagents and plasticware, regularly decontaminating work surfaces with specific RNase-inactivating solutions, and designating a special area for RNA work only. Autoclaving alone is not sufficient to eliminate RNases [4] [3] [5].

FAQ 4: How should I store purified RNA for long-term stability? For long-term storage, it is best to store RNA as a salt/alcohol precipitate at -20°C or in aliquots at -70°C to -80°C in RNase-free water or TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA). Aliquoting prevents degradation from repeated freeze-thaw cycles. The EDTA in the TE buffer chelates divalent cations, preventing metal-catalyzed hydrolysis [2] [4] [3].

FAQ 5: Can I use RNase inhibitors for all my RNA applications? RNase inhibitors are highly effective in protecting RNA during enzymatic reactions like reverse transcription and in vitro transcription. However, they are proteins and will be denatured and inactivated by the strong denaturants (e.g., guanidine salts, SDS) found in most lysis buffers used during RNA isolation. Therefore, they are not recommended for addition to cell lysates prior to purification [6].

Troubleshooting Common RNA Integrity Issues

Problem: Degraded RNA on Gel or Bioanalyzer

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smear on gel/electropherogram | RNase contamination during handling or isolation [2] | Decontaminate workspaces and equipment; use fresh RNase-free tips and tubes; include RNase inhibitors in reactions. |

| Slow sample processing after collection [4] | Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection or use RNA stabilization reagents (e.g., RNAlater). | |

| Discrete bands below main rRNA bands | Chemical hydrolysis during storage or heating [2] | Store RNA at -80°C in TE buffer (with EDTA); include a chelating agent when heating RNA samples. |

| No RNA detected | Over-degradation or incomplete isolation from samples rich in RNases [7] | Ensure tissues are homogenized directly in a denaturing lysis buffer; use a robust isolation method like organic extraction. |

Problem: Poor Yield in Downstream Applications (e.g., RT-PCR)

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High CT values or amplification failure | Trace RNase contamination in reagents or enzymes [5] | Test water and buffer stocks for RNase contamination; use a high-quality, broad-spectrum RNase inhibitor in master mixes. |

| RNA degradation during repeated freeze-thaw cycles [4] | Store RNA in single-use aliquots to avoid repeated freezing and thawing. | |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Inadequate homogenization or sample handling [4] | Standardize sample collection and homogenization protocols; keep samples on ice throughout processing. |

Understanding the Mechanisms of RNA Degradation

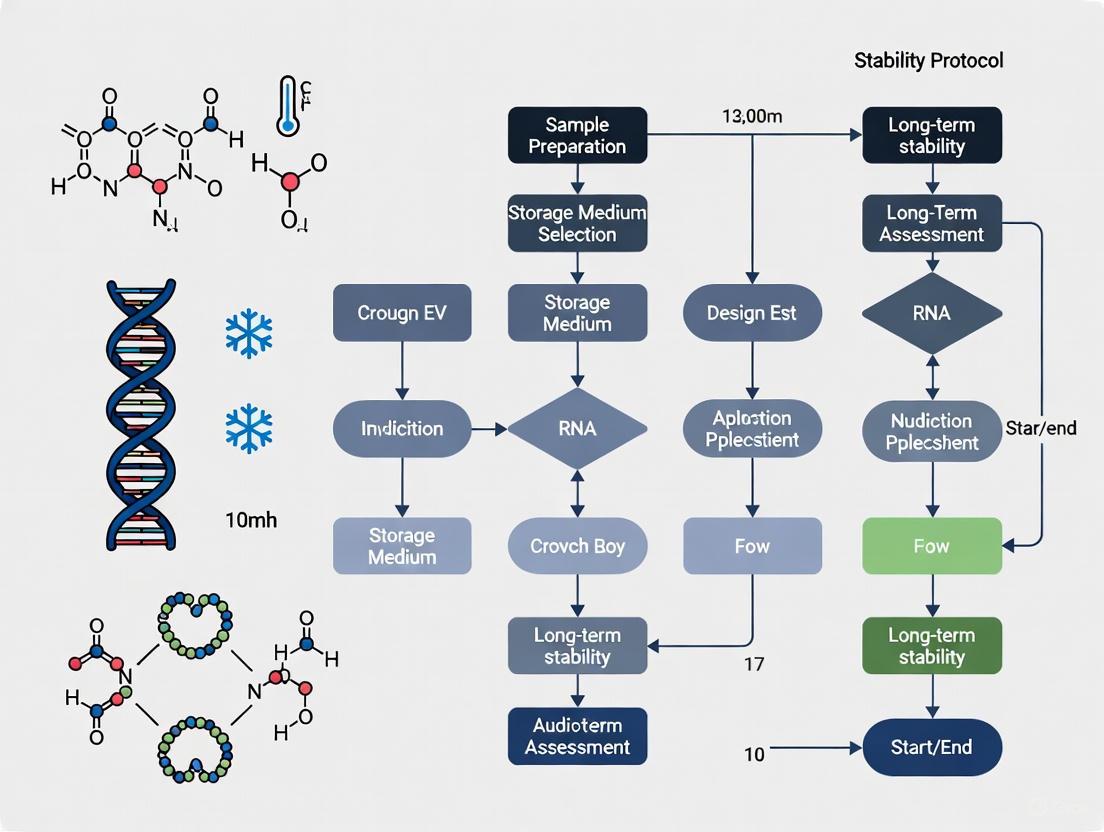

The following diagram illustrates the two primary pathways that lead to RNA degradation, highlighting its intrinsic structural vulnerabilities.

Quantitative Impact of Key Factors on RNA Stability

Table: Factors Influencing RNA Degradation Rates

| Factor | Mechanism of Action | Effect on RNA Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Divalent Cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) | Catalyze strand scission via in-line hydrolysis, especially at temperatures >80°C [2] [4]. | Significant decrease. Chelation with EDTA is critical for stabilization. |

| pH Level | Alkaline conditions (pH >8) increase availability of hydroxide ions, activating the 2'-OH group and accelerating hydrolysis [1]. | Stability decreases as pH increases. Neutral to slightly acidic conditions are preferred. |

| Temperature | Increases molecular energy, accelerating both enzymatic and chemical degradation. Each 10°C increase can double degradation rate. | Major decrease. For long-term storage, -80°C is required; samples should always be kept on ice during handling [4] [3]. |

| RNase Contamination | Enzymatic cleavage of phosphodiester bonds. RNases are stable and require strong chemical agents for deactivation [2]. | Rapid and complete degradation. A zero-tolerance policy for RNases is necessary. |

Experimental Protocols for Ensuring RNA Integrity

Protocol 1: Creating and Maintaining an RNase-Free Workspace

Principle: Prevent the introduction of RNases into samples through rigorous environmental control [2] [4] [3].

Procedure:

- Designate an RNA-only zone: Set aside a dedicated bench area, pipettes, and centrifuge for RNA work.

- Surface decontamination: Before use, thoroughly clean all surfaces (benches, pipettors, tube racks) with an RNase-decontaminating solution (commercial sprays or towelettes) or a 0.1% DEPC-treated solution. Note: Autoclaving alone is insufficient.

- Use disposable materials: Whenever possible, use sterile, disposable plasticware (tubes, tips) that are certified RNase-free.

- Treat non-disposables:

- Glassware: Bake at 180-250°C for at least 4 hours.

- Plasticware: Soak in 0.1 M NaOH / 1 mM EDTA for 2 hours, then rinse thoroughly with DEPC-treated water.

- Personal precautions: Always wear gloves and a lab coat. Change gloves frequently, especially after touching potentially contaminated surfaces like door handles or computer keyboards.

Protocol 2: Optimal Storage and Handling of RNA Samples

Principle: Minimize both enzymatic and chemical degradation pathways during storage [2] [4] [3].

Procedure:

- For Short-Term Storage (up to 1 month):

- Resuspend purified RNA in RNase-free water containing 0.1 mM EDTA or TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH ~7.5).

- Store at -80°C in single-use aliquots.

- For Long-Term Storage (over 1 month):

- The most stable method is to store the RNA as a precipitate in a solution of 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 70% ethanol at -20°C or -80°C. The low temperature, presence of alcohol, and slightly acidic pH all inhibit degradation.

- Alternatively, store aliquots in TE buffer at -80°C.

- Handling:

- Always keep RNA samples on ice when not in storage.

- Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Determine the required amount and create single-use aliquots upon initial purification.

- When thawing, gently mix by flicking the tube. If necessary, briefly vortex at low speed.

Protocol 3: Testing for RNase Contamination in Reagents

Principle: Proactively detect RNase contamination in lab-prepared buffers and water sources to prevent experimental failure [2] [5].

Procedure:

- Prepare a test solution: Mix a small aliquot (e.g., 35 µL) of the reagent to be tested with a known intact RNA (e.g., 5 µg).

- Set up controls:

- Positive Control: RNA + RNase-free water.

- Test Reaction: RNA + reagent.

- Protected Reaction: RNA + reagent + a broad-spectrum RNase inhibitor (e.g., 40 U RNasin).

- Incubate: Incubate all samples at 37°C for 1 hour to overnight.

- Analyze: Run the samples on a denaturing agarose gel or an Agilent Bioanalyzer.

- Intact RNA bands in all samples indicate the reagent is RNase-free.

- Degraded RNA (smear) in the "Test Reaction" but not in the "Protected Reaction" confirms RNase contamination in the reagent.

The workflow below summarizes the key steps for testing reagents.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for RNA Stabilization and RNase Control

| Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| DEPC (Diethyl Pyrocarbonate) | An alkylating agent that covalently modifies histidine residues in RNases, irreversibly inactivating them. Used to treat water and buffers [3]. | Making RNase-free water and solutions (except for Tris buffers, which it reacts with). |

| RNase Inhibitor Proteins | Proteins that non-covalently bind to and inhibit a broad spectrum of RNases (e.g., RNase A, B, C) [5] [6]. | Protecting RNA during enzymatic reactions like RT-PCR, in vitro transcription, and cDNA synthesis. |

| Guanidine Isothiocyanate | A powerful chaotropic agent that denatures and inactivates RNases upon cell lysis. A key component in many RNA isolation kits [4] [7]. | RNA extraction from cells and tissues; component of lysis buffers in spin-column and organic extraction methods. |

| RNA Stabilization Solutions (e.g., RNAlater) | Aqueous solutions that rapidly permeate tissues/cells to stabilize and protect RNA by inactivating RNases. Allows samples to be stored at room temperature for short periods or at 4°C/-20°C for longer periods [7]. | Preserving RNA integrity in tissues immediately after dissection, especially when processing many samples. |

| Chelating Agents (EDTA, Citrate) | Bind divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺), preventing metal-catalyzed hydrolysis of the RNA backbone [2] [4]. | Component of RNA storage buffers (e.g., TE buffer) and lysis buffers; essential in reactions involving heat denaturation of RNA. |

Ribonucleases (RNases) constitute a class of enzymes that catalyze the degradation of RNA into smaller components and are found in all domains of life, including viruses [8]. Their extreme stability and relentless activity make them a pervasive threat in laboratories working with RNA and Extracellular Vesicles (EVs). For researchers focused on the long-term storage of RNA and EV samples, understanding and mitigating RNase activity is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement for achieving reliable, reproducible results. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help you safeguard your valuable samples throughout your research workflow.

FAQ: Understanding the RNase Threat

This section answers the most common and critical questions regarding RNase stability and its implications for your research.

Q1: Why are RNases considered such a significant threat in RNA and EV research?

RNases are a major concern due to their ubiquity, remarkable stability, and catalytic efficiency.

- Ubiquity: RNases are found in almost all living organisms and are abundant in skin, hair, and bodily secretions. They are also common environmental contaminants [4].

- Stability: Many RNases, like RNase A, are exceptionally hardy. For instance, RNase A is so stable that one common purification method involves boiling a crude cellular extract to denature all other enzymes, leaving RNase A active [8].

- Cofactor Independence: Most RNases do not require cofactors to function, meaning they can remain active in various environments and even in purified water if introduced [4].

- Direct Impact on EVs: For EV research, RNase activity can degrade the RNA cargo within vesicles, compromising studies on EV-based communication, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development [9] [10].

Q2: What are the primary sources of RNase contamination in my lab?

The main sources can be categorized as follows:

- Endogenous: Originating from within your own biological sample. When cells or tissues are lysed, their native RNases are released [4].

- Exogenous: Introduced from the external environment. Key sources include:

Q3: How does the stability of RNases impact long-term sample storage?

The stability of RNases means that the threat of RNA degradation persists throughout the storage period. Without proper stabilization, RNA within samples or purified RNA preparations can degrade even at low temperatures, though the rate is slowed. This is why simply freezing samples is often insufficient; stabilization agents that inactivate RNases are critical for preserving an accurate snapshot of the RNA profile at the time of collection, which is essential for longitudinal studies and biobanking [11] [4] [12].

Q4: What is a Ribonuclease Inhibitor and when should I use it?

A Ribonuclease Inhibitor (RI) is a protein that binds to certain RNases with extremely high affinity, effectively neutralizing their activity [13]. It is a crucial tool for protecting RNA during in vitro manipulations.

- Function: Recombinant RI binds tightly and irreversibly to RNases like RNase A, B, and C, forming a stable complex that prevents RNA degradation [14].

- When to Use: RI is indispensable in enzymatic reactions involving RNA, such as cDNA synthesis, in vitro transcription, and RT-PCR [14]. It is typically added directly to the reaction mix to safeguard the RNA template.

- Important Note: RI is a cytosolic protein and is primarily used in vitro. It is not a substitute for proper sample handling and storage protocols for whole tissues or biofluids.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RNase-Related Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Degraded RNA samples (e.g., smeared gel, low RIN) | RNase contamination during handling or from non-sterile supplies; Inadequate sample stabilization before storage [4]. | Use RNase-free consumables; clean surfaces with RNase-deactivating reagents; wear gloves; use stabilization reagents (e.g., RNAlater) for tissues immediately upon collection [11] [4]. |

| Inconsistent RT-qPCR or RNA-seq results | Variable RNA degradation due to RNase activity, often from repeated freeze-thaw cycles of samples or RNA extracts [4]. | Aliquot RNA samples into single-use portions; avoid repeated thawing; store at -70°C or lower for long-term preservation [4]. |

| Low yield in cDNA synthesis or IVT | RNase degradation of the RNA template during the enzymatic reaction [14]. | Include a recombinant RNase Inhibitor in the reaction mixture according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., 1-2 U/µL) [14]. |

| Loss of EV RNA cargo or function | Degradation during biofluid storage prior to EV isolation [9] [10]. | For urine, add protease inhibitors and store at -80°C [9] [10]. For milk, remove cells and fat prior to storage to avoid contamination from stress-induced EVs [9]. |

Quantitative Data: RNase Degradation Kinetics and Storage Stability

Understanding the quantitative aspects of RNA degradation and stability under various conditions is vital for planning long-term storage. The following table summarizes key data from research.

Table 1: RNA Degradation Kinetics and Stability in Different Conditions

| Condition | Degradation Rate / Stability Outcome | Experimental Context & Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Room Temperature (Stabilized) | Extrapolated degradation rate of 0.7–1.3 cuts/1000 nt/century [12]. | RNA dried with a stabilizer in anoxic, anhydrous capsules. Major finding: atmospheric humidity is a primary degradation factor. |

| Long-term Tissue Storage | RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) >9 after 2 years, 7 months [11]. | Mouse tissues stored in RNAlater at -20°C. Gene expression profiles showed very high correlation (R=0.994) with fresh-frozen controls. |

| Urine Storage (for EVs) | EV yield decreases within 2 hours of collection; optimal recovery at -80°C [9] [10]. | Protease inhibitors improve yield. Vortexing after thawing from -80°C restored 100% EV-associated protein recovery. |

Table 2: Affinity of Ribonuclease Inhibitor (RI) for Various Ribonucleases

| Ribonuclease | Equilibrium Dissociation Constant (Kd) | Binding Affinity |

|---|---|---|

| Angiogenin (ANG) | 7.1 x 10⁻¹⁶ M [13] | Highest affinity |

| RNase 2 (EDN) | 9.4 x 10⁻¹⁶ M [13] | Extremely high affinity |

| RNase 4 | 4.0 x 10⁻¹⁵ M [13] | Very high affinity |

| RNase A | 4.4 x 10⁻¹⁴ M [13] | Very high affinity |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Storage Methods

Protocol 1: Validating a Room-Temperature RNA Storage Technology

This protocol is based on a study that demonstrated long-term room-temperature RNA stability [12].

Objective: To evaluate the integrity of RNA stored in a stabilizer within an airtight, anhydrous environment over time and at elevated temperatures.

Materials:

- Purified RNA sample.

- RNA stabilizer (commercial or as described in the study).

- Air-tight stainless-steel minicapsules or equivalent.

- Equipment: Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer or similar for RNA Integrity Number (RIN) calculation, Thermocycler for accelerated aging.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Mix the RNA with the chosen stabilizer solution.

- Encapsulation: Pipette the RNA-stabilizer mixture into minicapsules and seal them tightly to create an anoxic and anhydrous environment.

- Accelerated Aging: For short-term validation, subject encapsulated samples to elevated temperatures (e.g., 90°C) for defined periods. The degradation rate follows the Arrhenius law, allowing extrapolation to room-temperature stability.

- Analysis:

- At each time point, retrieve samples and resuspend the RNA in RNase-free water.

- Analyze RNA integrity using the Bioanalyzer to generate RIN values.

- Perform downstream functional assays like reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) to compare Cycle quantification (Cq) values between stored and fresh RNA.

Expected Outcome: Properly stabilized and encapsulated RNA should show minimal degradation (high RIN, minimal change in Cq values) even after accelerated aging, predicting stability for decades at room temperature [12].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Biofluid Storage for EV-RNA Preservation

This protocol outlines the assessment of pre-processing storage conditions for EV-containing biofluids like urine and plasma [9] [10].

Objective: To determine the impact of different storage temperatures and additives on the yield and RNA content of isolated EVs.

Materials:

- Freshly collected biofluid (e.g., urine, plasma).

- Protease inhibitor cocktail.

- Storage conditions: -80°C, -20°C, 4°C.

- Low-speed centrifuge.

- EV isolation kit (e.g., based on precipitation, size-exclusion chromatography).

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) instrument or similar for EV concentration.

- RNA isolation kit and Bioanalyzer.

Method:

- Aliquoting: Divide the fresh biofluid into multiple aliquots.

- Additive Conditions: Add protease inhibitors to some aliquots, leave others untreated.

- Storage: Store aliquots under different conditions (-80°C, -20°C, etc.) for a set duration (e.g., 1 week).

- EV Isolation: After storage, thaw samples (vortex thoroughly if frozen) and isolate EVs using your chosen method.

- Analysis:

- EV Yield: Use NTA to determine the concentration and size distribution of isolated particles.

- RNA Assessment: Isolate RNA from the EV fraction and analyze its integrity (RIN) and quantity.

Expected Outcome: Samples stored at -80°C with protease inhibitors are expected to show the highest EV yield and best-preserved RNA integrity, while storage at higher temperatures or without additives will likely result in reduced yield and degraded RNA [9] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for RNase Management

The following table lists key reagents and tools essential for combating RNases in a research setting.

Table 3: Key Reagents for RNase Inhibition and RNA Stabilization

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Recombinant RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA from degradation during in vitro enzymatic reactions like cDNA synthesis and IVT. Binds irreversibly to RNases [14]. |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | An aqueous, non-toxic reagent that permeates tissues to stabilize and protect RNA immediately upon collection. Allows for short-term non-frozen storage and long-term storage at -20°C [11]. |

| RNA Preserve | A liquid stabilizer for various samples (tissue, bacteria, soil). Enables room-temperature storage and shipping for periods from days to weeks [15]. |

| RNase-Deactivating Reagents | Sprays and solutions used to decontaminate work surfaces, glassware, and equipment to create an RNase-free environment [4]. |

| DEPC-treated Water | Diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) treatment inactivates RNases in water, making it safe for use in RNA-related experiments [4]. |

Workflow Visualization: Safeguarding Your Samples

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and recommended practices for protecting your RNA and EV samples from RNases throughout the experimental workflow.

RNase Mitigation Workflow: This diagram outlines the key steps and critical decisions for protecting RNA and EV samples from RNases, from collection through to analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on EV Membrane Integrity

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of physical stress that can damage EV membranes during handling? The primary sources of physical stress include freeze-thaw cycles, excessive pressure during concentration, and exposure to inappropriate storage temperatures [16] [17]. During isolation, techniques like tangential flow filtration (TFF) require careful monitoring of flow rate and pressure, as high shear forces can deform or rupture vesicles [17]. Furthermore, aggressive centrifugation or passing samples through narrow-gauge needles can cause mechanical shearing, compromising membrane integrity [4].

FAQ 2: Why are repeated freeze-thaw cycles detrimental to EV integrity? Repeated freeze-thaw cycles can cause EVs to rupture, aggregate, and lose their functional cargos [16] [17]. The formation and melting of ice crystals generate mechanical forces that physically disrupt the lipid bilayer. This damage leads to a decrease in particle number, a change in size distribution, and the degradation of encapsulated RNA and proteins [17]. To ensure reproducibility in downstream assays, it is critical to aliquot EVs into single-use volumes to avoid repeated thawing [17].

FAQ 3: How does improper storage temperature affect the stability of isolated EVs? Isolated EVs resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) are unstable at 4°C for extended periods, exhibiting a loss of particle number and surface markers [16] [17]. For long-term storage, -80°C or lower is recommended [16]. However, even at -80°C, standard freezing without cryoprotectants can be damaging. Lyophilization (freeze-drying) with specialized buffers presents a more stable alternative for room-temperature storage, preserving vesicle structure and function [17].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for concentrating large volumes of EV-containing conditioned media without causing damage? Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) is a recommended method for concentrating large volumes (>250 mL) as it is a scalable and gentle process that preserves EV integrity [17]. Key best practices include:

- Using membranes with appropriate molecular weight cut-offs (e.g., 100 kDa, 300 kDa).

- Monitoring flow rate and pressure to avoid high shear forces that can deform vesicles.

- Avoiding over-concentration, which can increase sample viscosity and lead to aggregation [17].

Troubleshooting Common EV Integrity Issues

Problem: Low Yield and Particle Aggregation After Isolation

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low particle count after isolation [17] | EV aggregation due to over-concentration or abrasive isolation techniques | Use gentle isolation methods like Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC); avoid high-pressure systems [17] |

| Visible precipitate in sample [17] | Aggregation from repeated freeze-thaw or freezing without cryoprotectants | Aliquot EVs into single-use volumes; use cryoprotectant buffers (e.g., EVSafe Storage Buffer) for freezing [17] |

| Inconsistent results in functional assays [17] | Damage to surface markers from physical stress, affecting recipient cell interaction | Minimize processing steps that introduce shear forces; validate surface markers with flow cytometry post-isolation [17] |

Problem: Degradation of RNA Cargo

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Degraded RNA in extracted EV cargo [17] | Membrane rupture from physical stress, exposing RNA to RNases | Use RNase-free reagents and techniques; avoid mechanical force like vortexing [4] [17] |

| Poor RNA quality from stored EVs [16] | Slow hydrolysis and enzymatic activity during storage | For long-term storage, lyophilize EVs with stabilizers or store at -80°C in single-use aliquots [16] [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Membrane Integrity

Protocol 1: Using Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS) for Size and Concentration Analysis

Purpose: To accurately measure the size distribution, concentration, and zeta potential of EV samples to identify aggregation or fragmentation resulting from physical stress [17].

Methodology:

- Instrument Calibration: Use lyophilized EV standards or silica nanoparticles to calibrate the Exoid or similar TRPS instrument [17].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the isolated EV sample in a particle-free electrolyte solution to achieve an appropriate concentration for measurement.

- Measurement: Load the sample into the instrument. TRPS works by measuring the change in electrical resistance (pulse) as each individual particle passes through a nanopore. The size of the pulse correlates with the particle's size, and the frequency of pulses indicates concentration [17].

- Data Analysis: Analyze the data for:

- Mean/Modal Size: A significant shift may indicate swelling or fragmentation.

- Polydispersity: An increase suggests a heterogeneous population, potentially from aggregation or breakdown.

- Particle Concentration: A drop may indicate aggregation or membrane rupture.

Protocol 2: Flow Cytometry with Fluorescent Membrane Stains

Purpose: To validate the integrity of the EV lipid bilayer and detect the presence of canonical surface proteins, confirming the isolation of intact vesicles rather than protein aggregates or debris [17].

Methodology:

- Staining: Incubate the EV sample with a membrane-permeant fluorescent stain, such as ExoBrite True EV Membrane Stain, which is designed to stain intact membranes with minimal induction of aggregation [17].

- Surface Marker Labeling (Optional): Combine the membrane stain with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against common EV surface markers (e.g., CD63, CD81, CD9) for a more comprehensive profile [17].

- Analysis: Run the sample on a flow cytometer capable of detecting nanoparticles. The presence of a double-positive population (membrane stain + surface marker) confirms intact EVs.

- Troubleshooting: Compare stained samples with unstained controls. A low signal for membrane stain may indicate a high proportion of ruptured vesicles.

Diagram: Mechanisms of Physical Stress on EV Integrity

The following diagram illustrates how different types of physical stress lead to the compromise of extracellular vesicle integrity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and kits used in EV research to preserve membrane integrity and ensure sample quality.

| Item | Function | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| EV-Depleted FBS [17] | Cell culture supplement | Provides essential growth factors while removing contaminating bovine EVs that could skew experimental results during EV production. |

| EVSafe Storage Buffer [17] | Cryoprotectant buffer | Maintains EV stability during freezing at -80°C, prevents aggregation, and preserves particle size distribution with high recovery (>95%). |

| EVSafe Lyophilisation Buffer [17] | Freeze-drying stabilizer | Enables long-term, ambient-temperature storage of EVs by preserving vesicle structure and function during the lyophilization process. |

| RNase-free reagents & kits [4] | Contamination prevention | Protects vulnerable RNA cargo from degradation by ubiquitous RNase enzymes during EV lysis and RNA extraction. |

| ExoBrite Membrane Stain [17] | Fluorescent dye | Selectively stains intact EV membranes for flow cytometry with minimal aggregation compared to traditional dyes like DiI or PKH. |

FAQs: Understanding Cryodamage and Lipid Bilayers

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms of cryodamage during the freezing of biological samples? Cryodamage primarily occurs through two key mechanisms: the formation, growth, and recrystallization of ice crystals, and the accompanying increase in solute concentration. Ice crystals can cause fatal mechanical injury to cells and subcellular structures like lipid bilayers. The formation of extracellular ice leads to cellular dehydration and osmotic pressure damage, while intracellular ice, which forms at higher cooling rates, is almost always lethal [18].

Q2: How do ice crystals specifically damage lipid bilayers? Lipid bilayers themselves can act as ice-nucleating agents, initiating damaging ice formation at temperatures well above the homogeneous freezing point of pure water. Molecular dynamics simulations show that phospholipid bilayers at the interface with supercooled water can facilitate ice nucleation. This ice formation can cause mechanical disruption and phase transitions within the membrane structure, compromising its integrity [19].

Q3: Why is the lipid bilayer a critical target for cryoprotective strategies? Membranes are a primary target for cryodamage. During cooling, lipid bilayers undergo phase transitions and structural changes that have been associated with cold shock damage. Small polar cryoprotectant molecules like DMSO can modulate the hydration layer of membranes, changing their properties at subzero temperatures and generating a high tolerance against the harmful effects of ice recrystallization [20].

Q4: How does cryodamage differ between slow freezing and rapid cooling (vitrification) methods? The mechanisms of injury differ significantly between these approaches [18]:

- Slow Freezing: Primarily causes extracellular ice formation, leading to cellular dehydration and solute concentration effects.

- Rapid Cooling/Vitrification: Aims to achieve an ice-free, glassy state. However, its main limitation is the potential formation of ice nucleation and devitrification (ice recrystallization) during the warming process, which can be fatal.

Q5: What role do lipid bilayers play in initiating ice formation? Research indicates that the complex chemical and structural factors of lipid bilayers make them potent ice-nucleating agents. This finding is a crucial first step in pinpointing the origin of extracellular ice nucleation, with major implications for understanding and improving cryopreservation protocols [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Cryopreservation Issues

| Problem | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low post-thaw cell viability (Slow freezing) | Excessive dehydration and solute damage from slow, extracellular ice formation. | Optimize cooling rate for your cell type; increase CPA concentration gradually; use controlled-rate freezing [18]. |

| Low post-thaw cell viability (Vitrification) | Devitrification and ice recrystallization during warming; CPA toxicity. | Increase warming rate; use lower toxicity CPAs (e.g., synthetic polymers); employ ice inhibitors [18]. |

| Intracellular ice formation | Cooling rate is too high, preventing water from exiting the cell. | Reduce the cooling rate to allow for sufficient cellular dehydration [18]. |

| Membrane rupture after thawing | Mechanical damage from ice crystals and/or loss of membrane integrity due to lipid phase transitions. | Use membrane-stabilizing CPAs like DMSO; modulate membrane composition (e.g., increase sterol content) [20]. |

| Contamination of EVs with lipoproteins (co-isolation) | Lipoproteins and EVs share similar physical properties like density and size. | Employ purification techniques that combine multiple principles (e.g., density gradient ultracentrifugation or affinity enrichment) to better separate EVs from contaminants [21]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Assessing Cryoprotectant Efficacy on Membrane Integrity via FRAP

This protocol uses Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) to investigate how cryoprotective agents (CPAs) influence plasma membrane fluidity, a key factor in cryotolerance [20].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Fluorescent Lipid: DiOC₁₈ for labeling the plasma membrane.

- Cryoprotective Agents: e.g., DMSO, ethylene glycol.

- Membrane Modulators: Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) loaded with cholesterol or ergosterol to alter membrane sterol content.

- Viability Stain: Propidium iodide (PI) to test membrane integrity post-thaw.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Use a standard cell line like HeLa cells.

- Treat one group with your chosen CPA (e.g., 15% DMSO + 15% ethylene glycol).

- For a comparative approach, treat another group with cholesterol-loaded MβCD (e.g., 10 mM for 60 mins) to artificially increase membrane sterol content without CPAs.

- Membrane Labeling: Label the living cells with the fluorescent lipid DiOC₁₈.

- FRAP Analysis:

- Select a small, uniform section of the plasma membrane on a confocal microscope and bleach it with a high-intensity laser pulse.

- Monitor the recovery of fluorescence into the bleached area over time.

- Calculate the diffusion speed and the mobile fraction of lipids.

- Correlation with Cryotolerance:

- Subject the treated cells to a rapid freeze-thaw cycle (e.g., in Open Pulled Straws in liquid nitrogen, rewarmed at 37°C).

- Assess plasma membrane integrity immediately by staining with propidium iodide (PI). Cells with compromised membranes will show red nuclear fluorescence.

Expected Outcome: Cells treated with CPAs or enriched with sterols will show the presence of an immobile lipid fraction in the membrane and significantly higher plasma membrane integrity after thawing compared to untreated controls [20].

Protocol: Comparing EV Isolation Methods for Purity and Yield

This protocol compares different extracellular vesicle (EV) isolation techniques from small plasma volumes, which is critical for ensuring high-quality, uncontaminated samples for long-term storage and research [21].

Methodology Overview:

- Sample Preparation: Collect human plasma (e.g., 100 μL aliquots) and pre-clear by centrifugation.

- EV Isolation (in triplicate): Isolate EVs using multiple methods based on different principles:

- Ultracentrifugation (UC): Traditional method pelleting EVs via high g-forces.

- Density Gradient UC (DGUC): Separates particles by density for higher purity.

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): e.g., qEV columns; separates by size.

- Polymer Precipitation: e.g., ExoQuick, Total Exosome Isolation kits; reduces EV solubility.

- Electrostatic Interaction: e.g., MagResyn SAX beads; binds negatively charged EVs.

- Affinity Enrichment: e.g., MagCapture beads; isolates phosphatidylserine-positive (PS+) EVs.

- Post-Isolation Processing: Concentrate and buffer-exchange all samples into PBS using 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff filters to ensure consistency.

- Characterization:

- Particle Analysis: Use Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for particle concentration and size distribution.

- Purity Assessment: Use Simple Western to detect canonical EV markers (e.g., CD9, CD81) and contaminants (e.g., albumin, ApoA1).

- Proteomic Profiling: Use LC-MS/MS for bottom-up proteomics to assess proteome coverage.

Summary of Quantitative Data from Comparative EV Isolation [21]:

| Isolation Method | Principle | Avg. Particle Size (nm) | Key Purity Indicators | Proteome Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Centrifugation | Wider distribution | Moderate contamination | Good |

| Density Gradient UC (DGUC) | Density | Wider distribution | Low contamination | Good |

| qEV Column (SEC) | Size | ~100-200 nm | Low to moderate contamination | Moderate |

| Polymer Precipitation | Solubility | Wider distribution | High contamination | Lower |

| MagNet / MagCap | Affinity / Electrostatic | Narrowest distribution | Highest purity | Highest |

Diagrams: Mechanisms and Workflows

Cryodamage Mechanisms During Freezing and Thawing

Cryoprotectant Mechanism of Action on Lipid Bilayers

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting RNA Degradation in Storage

- Problem: RNA samples show signs of degradation (e.g., smeared bands on gel, low RIN scores) after storage.

- Question: Are divalent cations and improper temperature the cause?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Assess Storage Buffer: Check if your storage buffer (e.g., TE buffer) contains EDTA or another chelating agent to sequester divalent cations like Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺. If not, the RNA is vulnerable to metal-catalyzed hydrolysis [4].

- Check Water Purity: Ensure that nuclease-free, ultrapure water is used to prepare storage solutions, as tap or low-grade purified water can be a source of metal ions [4].

- Verify Storage Temperature: Confirm that RNA aliquots are stored at -70°C or below for long-term preservation. Storage at -20°C is insufficient for prolonged periods and accelerates degradation [22].

- Minimize Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Divide RNA into small, single-use aliquots. Repeated freezing and thawing can reactivate RNases and promote hydrolysis [4].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting EV Aggregation and Cargo Loss

- Problem: Isolated EV preparations show aggregation, a change in size distribution, or loss of RNA cargo upon thawing.

- Question: Did temperature fluctuations during storage cause this damage?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Audit Freezing Protocol: Avoid storing EVs at -20°C. For long-term storage, freeze EV samples at a constant -80°C. Rapid freezing (snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen) is recommended before transfer to -80°C to prevent ice crystal formation [23].

- Eliminate Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Subjecting EVs to multiple freeze-thaw cycles significantly decreases particle concentration, impairs bioactivity, and increases size due to aggregation. Always store in single-use aliquots [23].

- Consider Stabilizers: For critical samples, add cryoprotectants like trehalose to the EV suspension before freezing. This helps maintain vesicle integrity and prevents membrane fusion [23].

- Check Storage Medium: Note that EVs stored in native biofluids (e.g., plasma, cell culture supernatant) often demonstrate better stability than those purified and resuspended in simple buffers [23].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are divalent cations like Mg²⁺ so problematic for RNA stability? The primary reason is their role in catalyzing RNA strand cleavage. The 2'-hydroxyl group on the ribose sugar of RNA can act as a nucleophile, attacking the adjacent phosphodiester bond. Divalent cations, particularly Mg²⁺, stabilize the transition state of this reaction, significantly accelerating hydrolysis and breaking the RNA backbone [1]. This makes them potent catalysts of RNA degradation.

FAQ 2: What is the recommended long-term storage temperature for RNA and EVs? For both RNA and EVs, -70°C to -80°C is the recommended temperature for long-term storage [23] [4] [22]. Storage at -20°C leads to significantly faster degradation of RNA and promotes aggregation and loss of function in EVs [23].

FAQ 3: How do different divalent cations compare in their effect on RNA stability? The destabilizing effect of a divalent cation is determined by its charge density (ζ). Cations with higher charge density are more effective at stabilizing the folded structure of RNA, but also more effectively catalyze its degradation when folded structure is not a factor. The following table summarizes the properties of common Group IIA cations [24]:

Table: Influence of Divalent Cations on RNA Folding Stability

| Cation | Ionic Radius (Å) | Charge Density (ζ, e/ų) | Relative Stabilization of Folded RNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg²⁺ | 0.65 | 0.055 | Highest |

| Ca²⁺ | 0.99 | 0.038 | High |

| Sr²⁺ | 1.13 | 0.027 | Medium |

| Ba²⁺ | 1.35 | 0.020 | Low |

FAQ 4: How many freeze-thaw cycles can my RNA or EV samples tolerate? Ideally, zero. Each cycle inflicts cumulative damage. For RNA, freeze-thaw cycles can lead to the reactivation of RNases and physical shearing [4]. For EVs, even a single cycle can cause a noticeable decrease in particle concentration and RNA content, with multiple cycles leading to extensive aggregation and functional loss [23]. Aliquotting is the most effective countermeasure.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Temperature and mRNA Length on Stability

| Factor | Experimental Condition | Key Finding | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Analysis of activation energy (Ea) for degradation | Ea = 31.5 kcal/mol normalized per phosphodiester backbone [25] | Thermodynamic analysis |

| mRNA Length | Comparison of different nucleotide lengths | Longer mRNA transcripts are negatively correlated with stability [25] | Integrity analysis via capillary electrophoresis |

| Storage Duration | EVs stored at -20°C vs. -80°C | EVs at -20°C showed significant aggregation and size increase after one month; -80°C preserved integrity [23] | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), Western Blot, functional assays |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring the Effect of Divalent Cations on RNA Hydrolysis

Objective: To quantify the rate of RNA strand cleavage catalyzed by different divalent cations.

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a solution of a defined, homogenous RNA transcript (e.g., 1-2 kb in length) in a chelating buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5).

- Dialyze the RNA extensively against a large volume of chelator-free buffer (e.g., 10 mM Na-Hepes, pH 7.0) to remove all divalent cations [24].

Reaction Setup:

- Aliquot the dialyzed RNA into separate tubes.

- To each tube, add a chloride salt of a divalent cation (MgCl₂, CaCl₂, SrCl₂, BaCl₂) to a final concentration of 1-10 mM. Include a no-cation control.

- Incubate all reactions at a defined temperature (e.g., 37°C or 50°C) for a set period (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8 hours) [1].

Analysis:

- Stop the reactions by adding excess EDTA (50 mM final concentration).

- Analyze the RNA integrity on a denaturing agarose or polyacrylamide gel. Intact RNA will appear as a sharp band, while degraded RNA will appear as a smear.

- Quantification: Use techniques like capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer) to calculate the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or the percentage of intact full-length transcript remaining [25].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Temperature-Induced EV Aggregation

Objective: To assess the physical stability of EVs under different storage temperatures and freeze-thaw cycles.

EV Isolation & Preparation:

- Isolate EVs from a cell culture supernatant (e.g., MSC-conditioned media) using a standardized method like size-exclusion chromatography or ultracentrifugation [23].

- Resuspend the purified EV pellet in a neutral buffer (e.g., PBS) or PBS with 5% trehalose.

Storage Conditions:

- Divide the EV suspension into multiple aliquots.

- Temperature Groups: Store aliquots at 4°C, -20°C, and -80°C. Include a subset snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at -80°C.

- Freeze-Thaw Groups: Subject a separate set of aliquots (stored at -80°C) to 1, 3, and 5 freeze-thaw cycles. Thaw cycles should be performed rapidly in a 37°C water bath [23].

Analysis:

- Concentration & Size: Use Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) to measure the particle concentration and mode/mean size before and after storage. An increase in size indicates aggregation.

- Morphology: Use transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to visually inspect for vesicle deformation, rupture, or fusion.

- Cargo Integrity: Isplicate RNA from the treated EVs and analyze miRNA or mRNA content using qRT-PCR or Bioanalyzer to assess cargo preservation [23].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

RNA Hydrolysis Catalyzed by Divalent Cations

EV Storage and Stability Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Stabilizing RNA and EV Samples

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺), preventing metal-catalyzed RNA hydrolysis [4]. | Standard component of RNA storage buffers (e.g., TE buffer). |

| RNAstable or RNAprotect | Commercial stabilization reagents that protect RNA integrity at room temperature by inhibiting RNases and hydrolysis [4]. | Useful for sample transport or short-term storage without freezing. |

| Trehalose | A disaccharide cryoprotectant that stabilizes lipid bilayers and proteins. Helps prevent EV aggregation and membrane fusion during freezing [23]. | Preferable to DMSO for EVs as it is non-cytotoxic and doesn't interfere with downstream applications. |

| RNase-free Water | Ultrapure, nuclease-free water for preparing storage buffers and resuspending RNA. Ensures no introduction of external RNases or metal ions [4]. | A critical baseline for all molecular biology workflows involving RNA. |

| PAXgene Tubes | Specialized blood collection tubes containing additives that immediately stabilize intracellular RNA profiles upon drawing blood [4]. | Essential for clinical biobanking and accurate gene expression studies from blood. |

Proven Protocols: Step-by-Step Storage Methods for Different Sample Types

A technical guide to safeguarding your precious RNA and EV samples

Ensuring the stability of biological samples like RNA and Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) is a cornerstone of reproducible research. The choice between -20°C for short-term needs and -80°C for long-term preservation is critical, impacting everything from sample integrity to experimental costs. This guide provides evidence-based protocols and troubleshooting tips to navigate this essential aspect of your work.

Troubleshooting Common Storage Problems

Q: My RNA samples underwent multiple freeze-thaw cycles. How might this affect my downstream analysis? A: Multiple freeze-thaw cycles are a significant source of RNA degradation. They can lead to:

- RNA Degradation: The repeated formation and melting of ice crystals can physically shear RNA molecules, resulting in fragmented RNA.

- Altered Gene Expression Data: Degraded RNA can skew results in sensitive applications like qRT-PCR and RNA sequencing, leading to inaccurate 3'/5' ratios and loss of transcript detection [26] [11].

- Solution: Always aliquot RNA into single-use portions to avoid repeated freezing and thawing. Consider room-temperature storage technologies for working aliquots [26] [27].

Q: I stored my purified EV samples at -20°C, and now I notice aggregation. What happened? A: Storage of purified EVs at -20°C is often suboptimal and can lead to:

- Vesicle Aggregation and Fusion: The -20°C environment can damage the EV lipid membrane, causing vesicles to clump together or merge, which alters their size distribution and concentration [23].

- Loss of Bioactivity: Membrane damage and aggregation can lead to the leakage of internal cargo (proteins, RNA) and impair the EV's functional activity in recipient cells [10] [23].

- Solution: For any storage beyond a few days, store purified EVs at -80°C. The use of cryoprotectants like trehalose can also help maintain membrane integrity [23].

Q: My samples are stored at -80°C, but the freezer is nearing capacity and is opened frequently. Should I be concerned? A: Yes, frequent opening of an -80°C freezer can compromise sample integrity.

- Temperature Fluctuations: Each opening introduces warm, moist air, causing the internal temperature to spike and promoting frost buildup. This subjects samples to partial thawing and refreezing, similar to the damaging effects of freeze-thaw cycles [28].

- Increased Degradation Rate: Even transient warming can increase the rate of hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation processes.

- Solution: Implement an organized sample management system. Use racks and maps for quick retrieval, keep a detailed inventory to minimize door-open time, and ensure the freezer is well-maintained with a clean condenser [28].

Storage Condition Comparison Tables

RNA Storage Conditions and Outcomes

| Sample Type | Storage Condition | Duration | Key Outcomes & Integrity Metrics | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Total RNA [26] | Room Temp (in RNAstable) | 4 weeks | RIN: 9.70 ± 0.00; OD 260/280: ~2.02; Microarray data identical to -80°C control [26] | Sample shipping; short-term working aliquots |

| Purified Total RNA [27] | Room Temp (in anhydrous capsules) | Theoretical: decades | Model predicts ~1 cut per 1000 nucleotides per century; stable Cq values in qPCR [27] | Ultra-long-term archiving (years) |

| Tissue for RNA [11] | RNAlater at -20°C | >2.5 years | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 9; gene expression profiles highly correlated with frozen samples (R=0.994) [11] | Long-term tissue preservation prior to RNA extraction |

| Purified Total RNA [26] | -80°C (standard) | Long-term | RIN > 9.7; considered the "gold standard" for frozen RNA preservation [26] [11] | Long-term master stock storage |

EV Storage Conditions and Outcomes

| Sample Type / Source | Storage Condition | Duration | Key Outcomes & Integrity Metrics | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified EVs (general) [23] | -80°C | Long-term (months) | Best preservation of concentration, size, morphology, RNA content, and bioactivity [23] | Long-term storage of purified EVs |

| Purified EVs (general) [23] | -20°C | >1 week | Significant particle aggregation, size increase, and potential loss of bioactivity [23] | Not recommended |

| Urine (for EV isolation) [10] | -80°C | 1 week | 100% EV-associated protein recovery with vortexing; higher yield than -20°C [10] | Storage of biofluid prior to EV isolation |

| MSC-derived EVs [23] | -80°C | 1 month | No significant change in uniform size, integrity, or bioactivity [23] | Storage of therapeutic EV candidates |

| Plasma (for EV isolation) [10] | -80°C | 20 months | Decrease in EV yield over time [10] | Note: Biofluid storage can impact yield |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Long-Term Room Temperature Storage of RNA using a Stabilizing Matrix

This protocol is adapted from studies evaluating RNAstable, a commercial product that protects RNA by embedding it in a dry, anhydrobiotic matrix at room temperature [26].

- Key Research Application: This method is ideal for maintaining the integrity of purified RNA for microarray analysis and other sensitive downstream applications without a cold chain.

Essential Materials:

- RNAstable tubes or plates (Biomatrica)

- Purified RNA sample (e.g., 250 ng/µl in RNase-free water)

- SpeedVac vacuum concentrator (without heat)

- Sealed moisture barrier bags with desiccant

Step-by-Step Method:

- Preparation: Aliquot your purified RNA sample (e.g., 20 µl) directly into the tube containing the RNAstable stabilizer.

- Drying: Place the tubes in a SpeedVac and dry without heat for approximately 30-60 minutes, or until the sample is completely dry.

- Storage: Transfer the dried samples into a sealed moisture barrier bag with a desiccant pack. Store the bag at room temperature, protected from light.

- Recovery: To use the sample, rehydrate it by adding the original volume of RNase-free water (e.g., 20 µl). Mix gently and use directly in downstream applications like spectrophotometry, bioanalyzer analysis, or microarray labeling without further purification [26].

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting:

- Incomplete Drying: Ensure the sample is completely dry before sealing for storage, as residual moisture can lead to degradation.

- Humidity Control: Always store the dried samples with a desiccant to maintain an anhydrous environment, which is crucial for long-term stability [27].

- Compatibility: The rehydrated sample is compatible with many downstream applications without purification, but it is advisable to validate this for highly sensitive assays.

Protocol 2: Preservation of Tissue Samples for RNA Using RNAlater

This protocol describes the use of RNAlater to stabilize RNA in fresh tissues, preventing degradation during collection and prior to RNA extraction [11].

- Key Research Application: Preserving gene expression profiles in tissues when immediate freezing in liquid nitrogen is not practical.

Essential Materials:

- RNAlater Tissue Collection Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

- Freshly dissected tissue samples (< 0.5 cm in one dimension)

- 1.5-2.0 ml microcentrifuge tubes

Step-by-Step Method:

- Collection: Immediately upon dissection, place the tissue sample into a 5x volume of RNAlater solution (e.g., 0.5 g tissue in 2.5 ml RNAlater).

- Permeation: Incubate the tube at 4°C for several hours (or overnight) to allow the solution to fully permeate the tissue.

- Long-Term Storage: After permeation, the sample can be stored at -20°C for several years. The solution does not solidify, allowing for easy handling and subsampling without thawing [11].

- RNA Extraction: When ready, remove the tissue from RNAlater and proceed with standard RNA isolation protocols (e.g., using TRIzol or silica-membrane kits). The RNA yield and quality (RIN > 9) will be comparable to that from flash-frozen tissue [11].

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting:

- Tissue Size: The tissue piece must be small enough for RNAlater to penetrate quickly; otherwise, the inner core may degrade.

- Delay in Preservation: For best results, submerge the tissue in RNAlater as quickly as possible after dissection to minimize any pre-stabilization degradation.

Protocol 3: Cryopreservation of Purified Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

This protocol outlines best practices for storing purified EVs to maintain their structural and functional integrity, based on a systematic review of storage conditions [23].

- Key Research Application: Long-term storage of therapeutic EV candidates or EV samples for downstream functional studies and omics analyses.

Essential Materials:

- Purified EV sample (in PBS or similar buffer)

- Cryogenic vials

- -80°C Freezer

- (Optional) Cryoprotectant (e.g., trehalose)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Aliquoting: Aliquot the purified EV preparation into single-use cryogenic vials to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Cryoprotection (Optional): For enhanced stability, consider adding a cryoprotectant like trehalose to a final concentration of 5-10% (w/v) before freezing. This helps protect the EV membrane [23].

- Freezing: Rapidly freeze the aliquots by placing them directly at -80°C. The use of a controlled-rate freezer is ideal but not always necessary.

- Storage: Maintain the samples at a constant -80°C. Avoid storing EVs at -20°C, as this leads to aggregation and loss of function [23].

- Thawing: When needed, thaw the EV aliquot quickly in a 37°C water bath and place it on ice. Gently mix by pipetting or inverting before use. Do not vortex vigorously.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting:

- Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles at all costs. Each cycle causes a dramatic decrease in particle concentration, impairs bioactivity, and increases aggregation [23].

- Storage Buffer: EVs stored in their native biofluid (e.g., plasma) often have better stability than those purified and stored in simple buffers like PBS. If possible, characterize EVs soon after isolation from the biofluid [23].

Visual Guide: Sample Storage Workflow

This diagram outlines the decision-making process for choosing the optimal storage strategy for your RNA and EV samples.

Visual Workflow for RNA and EV Sample Storage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| RNAlater [11] | Stabilizes RNA in tissues and cells at collection; enables storage at 4°C, 25°C (short-term), or -20°C (long-term). | Prevents the need for immediate flash-freezing. Ideal for field work and multi-site studies. |

| RNAstable [26] | Matrix for room-temperature storage of purified RNA in a dry state. Protects against degradation for weeks. | Eliminates cold chain for RNA storage and shipping. Samples are recovered by simple rehydration. |

| Anhydrous Minicapsules [27] | Air- and water-tight containers for RNA storage under an anhydrous, anoxic atmosphere. | Enables theoretical room-temperature storage for decades by eliminating atmospheric humidity. |

| Trehalose [23] | A cryoprotectant used to stabilize EV membranes during freezing at -80°C, reducing aggregation and preserving function. | A non-toxic alternative to DMSO for protecting lipid bilayers from cryo-damage. |

| -80°C Freezer | Primary workhorse for long-term storage of RNA master stocks, purified EVs, and biofluids intended for EV isolation. | Requires consistent power and maintenance. Organize samples to minimize temperature fluctuations. |

| SpeedVac Concentrator | Used to dry down RNA samples in the presence of stabilizers like RNAstable for room-temperature storage. | Using no-heat or low-heat settings is critical to avoid heat-induced RNA degradation during drying. |

Key Takeaways for Optimal Sample Storage

- For RNA: The paradigm is shifting from purely cold-chain reliance. While -80°C remains the gold standard for long-term archives, RNAlater (-20°C) is superior for tissue preservation, and novel room-temperature technologies now offer robust, cost-effective solutions for purified RNA [26] [11] [27].

- For EVs: -80°C is unequivocally required for any meaningful medium- to long-term storage of purified EVs. Storage at -20°C is detrimental, leading to aggregation and functional loss. Minimize freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting [10] [23].

- Universal Rule: Plan, aliquot, and minimize temperature fluctuations. Whether working with RNA or EVs, proactive sample management is the most effective strategy to ensure integrity and the reproducibility of your research outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind using liquid nitrogen for flash-freezing? Liquid nitrogen flash-freezing works by leveraging the extreme cold temperature of liquid nitrogen (-196°C / -320°F) to rapidly absorb heat from a biological sample [29]. When the liquid nitrogen changes from a liquid to a gas, it absorbs a significant amount of energy (about 199 kJ/kg) from its surroundings [29]. This rapid heat transfer causes the water within the sample to freeze almost instantaneously, preventing the formation of large, disruptive ice crystals and halting biological and chemical degradation processes [29] [30].

Q2: Why is flash-freezing crucial for preserving RNA integrity in research samples? RNA is particularly vulnerable to degradation by RNases, which are ubiquitous and stable enzymes [4]. The rapid temperature drop achieved by liquid nitrogen flash-freezing instantly inactivates these RNases, "locking" the RNA in its native state at the moment of collection [4] [3]. This prevents degradation that would otherwise occur during slower freezing and is essential for obtaining accurate gene expression profiles in downstream applications [4].

Q3: What is the difference between vapor phase and liquid phase storage in a liquid nitrogen freezer? Liquid nitrogen freezers offer two primary storage methods, each with distinct advantages [29]:

| Storage Phase | Temperature Range | Key Advantages | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vapor Phase | -135°C to -190°C [29] | Reduces cross-contamination risk; preferred for biological specimens [29]. | Temperature gradient exists (warmer at top); requires careful sample placement [29]. |

| Liquid Phase | Consistent -196°C [29] | Uniform, ultra-low temperature; eliminates temperature gradients [29]. | Higher risk of cross-contamination; consumes more nitrogen [29]. |

Q4: What are cryoprotective agents (CPAs) and when are they needed? Cryoprotective Agents (CPAs) are substances used to protect cells and tissues from freezing damage (cryoinjury) caused by ice crystal formation and osmotic stress during the freezing process [31]. They are often essential for complex biological samples like tissues, organelles, or certain cell types. CPAs are categorized as:

- Permeating CPAs: These can enter cells (e.g., Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Glycerol) and help prevent intracellular ice formation [31].

- Non-Permeating CPAs: These do not enter cells (e.g., polymers like hydroxyethyl starch, sugars) and work by increasing the solute concentration outside the cell, drawing water out and reducing the chance of intracellular ice formation [31].

The choice and concentration of CPA must be optimized for each sample type to balance protection against potential toxicity [31].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low RNA Yield/Quality After Thawing | RNase activation or degradation during slow/pre-freezing handling [4] [32]. | Flash-freeze samples immediately after collection [4] [3]. Use RNase-free tubes and tools. For tissues, grind under liquid nitrogen before homogenization [4]. |

| Sample Cross-Contamination | Direct contact with liquid nitrogen during storage [29]. | Store samples in the vapor phase of the liquid nitrogen freezer instead of submerging them in the liquid [29]. Ensure all sample containers are tightly sealed. |

| Low Cell Viability Post-Thaw | Intracellular ice crystal formation damaging cellular structures [31]. | Use an appropriate Cryoprotective Agent (CPA), such as DMSO or glycerol [31]. Optimize the freezing protocol (cooling rate) for your specific cell type [31]. |

| Cracks or Breaks in Storage Tubes | Liquid nitrogen entering improperly sealed containers and expanding rapidly upon warming [29]. | Use cryogenic vials designed for low temperatures and ensure they are tightly sealed before immersion. Avoid using microfuge tubes not rated for liquid nitrogen storage. |

| High Liquid Nitrogen Consumption | Frequent opening of freezer lid, poor insulation, or using liquid phase storage [29]. | Minimize how long the freezer chamber is open. Ensure the freezer's seals and vacuum insulation are intact. Consider switching to vapor phase storage, which typically uses less nitrogen [29]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Flash-Freezing & Storage |

|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen | Primary cryogenic fluid for rapid freezing and maintaining long-term storage at -196°C [29]. |

| Cryoprotective Agents (CPAs) | Protect cellular integrity from ice crystal damage during freeze-thaw cycles [31]. Examples: DMSO, Glycerol. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protect RNA from degradation by RNase enzymes during sample preparation prior to freezing [3]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Chemically stabilize RNA in tissues or cells at room temperature before freezing (e.g., RNAlater) [4]. |

| Cryogenic Vials | Specially designed tubes that can withstand extreme temperatures without cracking [29]. |

| Double-Walled Vacuum Chambers | Highly insulated storage containers that minimize heat transfer and reduce liquid nitrogen evaporation [29]. |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Flash-Freezing Procedure for Tissue Samples

This protocol is designed for stabilizing RNA in freshly excised tissue samples.

Materials Needed:

- Liquid nitrogen in a dedicated dewar or shallow container [29]

- Cryogenic vials [29]

- Pre-cooled mortar and pestle or cryo-mill [4]

- Forceps, aluminum foil or weighing boats

- Labels and a permanent marker

- Personal protective equipment (insulated gloves, lab coat, face shield) [29]

Method:

- Preparation: Pre-cool the mortar and pestle by adding a small amount of liquid nitrogen. Label cryogenic vials and place them on a rack accessible near the liquid nitrogen.

- Sample Collection: Excise the tissue as quickly as possible.

- Rapid Freezing:

- Option A (Direct Immersion): For smaller tissues (<1 cm³), use forceps to gently dip the sample directly into the liquid nitrogen for 10-30 seconds until fully frozen. Transfer immediately to a pre-cooled cryovial and place it on dry ice or directly into a -80°C freezer before long-term storage [3].

- Option B (Flash-Freezing on a Platform): For smaller or more fragile tissues, place a small boat made of aluminum foil or a weighing boat on the surface of the liquid nitrogen to let it cool. Place the tissue sample on this chilled platform to freeze. This prevents the violent boiling that can occur with direct immersion.

- Grinding (Optional but Recommended for RNA): For optimal RNA extraction, grind the frozen tissue to a powder while keeping it submerged in liquid nitrogen. Add the frozen tissue to the pre-cooled mortar and grind vigorously with the pestle until a fine powder is formed.

- Transfer and Storage: Use a pre-cooled spatula to transfer the powdered tissue to a labeled cryogenic vial. Close the vial tightly and immediately transfer it to a pre-cooled box in a vapor-phase liquid nitrogen freezer or a -80°C freezer for long-term storage [29] [3].

- Documentation: Record all sample details, including storage location, date, and any specific freezing conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary mechanism of action for RNAlater and TRIzol?

- RNAlater is an aqueous, non-toxic solution that rapidly permeates tissues to inactivate RNases and stabilize RNA, allowing samples to be stored without immediate freezing [33].

- TRIzol is a mono-phasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate that denatures proteins and RNases upon contact. It disrupts cells and separates RNA into the aqueous phase during a subsequent chloroform addition and centrifugation step [34].

Q2: My RNA pellet is invisible after precipitation with TRIzol. What should I do? An invisible pellet often indicates a very low RNA concentration [34]. You can:

- Precipitate at lower temperatures: After adding isopropanol, precipitate at 4°C or -20°C for 10–30 minutes [34].

- Use a carrier: Add a carrier such as glycogen, linear polyacrylamide, or salmon sperm DNA to improve the recovery of nucleic acids [34] [22].

- Avoid decanting: To prevent losing the pellet, use pipetting to remove the supernatant instead of decanting [34].

Q3: How do I handle tissue samples for RNA stabilization in the field where liquid nitrogen is not available? RNAlater is ideal for this purpose [33] [35]. The standard protocol is:

- Excise the tissue and quickly cut it into pieces less than 0.5 cm in one dimension to allow for penetration.

- Submerge the tissue completely in 5-10 volumes of RNAlater (e.g., 2.5 mL for a 0.5 g sample).

- The sample can then be stored at 4°C for about a month, at 25°C for a week, or at -20°C indefinitely before RNA extraction [33] [36].

Q4: The aqueous phase has an abnormal color after phase separation with TRIzol. What does this mean? An abnormal color (e.g., yellow-brown, pink, or red) is often sample-specific [34]:

- Blood-rich samples: Hemoglobin can cause yellowing or turbidity. Pre-wash tissues with PBS to reduce blood content [34].

- Lipid-rich tissues: Lipids can carry pigments into the aqueous layer. Centrifuge the homogenate before chloroform addition to remove the lipid layer from the top [34].

- High salt/protein content: This can cause premature phase separation. Ensure you are not exceeding a 1:10 sample-to-TRIzol ratio and consider increasing the TRIzol volume [34].

Q5: My RNA is contaminated with genomic DNA. How can I remove it? DNA contamination is a common issue in RNA isolation [37]. The most effective solution is to include a DNase I treatment step [22] [37]. Many commercial RNA isolation kits offer an "on-column" DNase digestion step for this purpose, which is efficient and avoids the need for extra clean-up steps [35]. For samples in TRIzol, ensure you are carefully pipetting only the aqueous phase and not disturbing the interphase, which contains DNA [37].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low RNA Yield [22] [37] | Incomplete homogenization; sample not fully lysed. | Ensure thorough homogenization; use mechanical disruption (e.g., bead beater) for tough tissues/cells. |

| RNA Degradation [22] [37] | RNase activity during sample handling; slow stabilization. | Stabilize samples immediately upon collection; add β-mercaptoethanol (BME) to lysis buffer; avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| DNA Contamination [37] | Inefficient separation; acidic phenol pH not maintained. | Perform an on-column or post-elution DNase I treatment; ensure proper technique when aspirating aqueous phase in TRIzol. |

| Abnormal A260/280 Ratio (Low Protein Contamination) [22] | Protein carryover; incomplete separation. | Re-purify the RNA with another round of phenol-chloroform or silica column; do not overload the kit capacity. |

| Abnormal A260/230 Ratio (Salt/Organic Contaminant Carryover) [37] | Guanidine salt or organic compound carryover. | Perform additional ethanol washes; for silica columns, wash with 70-80% ethanol; ethanol-precipitate the RNA to desalt. |

| No Interphase in TRIzol Separation [34] | Insufficient mixing after chloroform addition; very low sample input. | Vortex thoroughly after chloroform addition until the mixture appears milky; proceed with caution for low-input samples and use a carrier. |

| Gelatinous or Colored RNA Pellet [34] [22] | Contamination with polysaccharides or proteoglycans (common in plants, insects). | For TRIzol, use a high-salt precipitation step (0.8 M sodium citrate & 1.2 M NaCl) with isopropanol to keep contaminants soluble. |

Experimental Protocols for Sample Stabilization and RNA Isolation

RNA Stabilization and Isolation from Tissues using RNAlater

This protocol is ideal for preserving RNA integrity when immediate RNA extraction is not possible [33] [36].

- Materials: RNAlater Solution, RNase-free tools, PBS (optional), RNA isolation kit (e.g., silica-column based or TRIzol).

- Procedure:

- Tissue Harvesting: Excise tissue promptly. Rinse briefly in PBS if heavily contaminated with blood, and blot dry.

- Dissection: Cut the tissue into small pieces (<0.5 cm in one dimension) to allow RNAlater to penetrate.

- Immersion: Submerge the tissue in 5-10 volumes of RNAlater (e.g., 0.5 g tissue in 2.5 mL RNAlater).

- Storage: Incubate overnight at 2-8°C, then store the sample at -20°C or -80°C indefinitely.

- RNA Isolation: Remove tissue from RNAlater. Proceed with standard RNA isolation protocols. Most tissues can be homogenized directly in lysis buffer. Harder tissues may need freezing in liquid N₂ and grinding [33] [36].

Total RNA Isolation using TRIzol Reagent

This is a robust, universal phenol-guanidine isothiocyanate-based method for a wide variety of samples [34] [22].

- Materials: TRIzol Reagent, Chloroform, Isopropanol, 75% Ethanol (in DEPC-treated water), RNase-free water.

- Procedure:

- Homogenization: Homogenize tissue or cells in TRIzol (e.g., 1 mL per 50-100 mg tissue). Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature to dissociate nucleoprotein complexes.

- Phase Separation: Add 0.2 mL of chloroform per 1 mL of TRIzol. Cap the tube securely, vortex vigorously for 15 seconds, and incubate at room temperature for 2-3 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Precipitation: Transfer the colorless upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Add an equal volume of isopropanol and mix. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes (or at -20°C for low concentration samples) to precipitate the RNA. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Wash: Remove the supernatant. Wash the RNA pellet with 75% ethanol by vortexing and centrifuging at 7,500 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Redissolving: Air-dry the pellet briefly (do not over-dry) and redissolve the RNA in RNase-free water by pipetting and incubating at 55-60°C for 10-15 minutes if necessary [34] [22].

Reagent Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three stabilization reagents to guide your experimental choice.

| Feature | RNAlater | TRIzol | RNAprotect / DNA/RNA Shield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Inactivates RNases by rapid permeation [33] | Denatures proteins and RNases with phenol/guanidine [34] | Inactivates nucleases and protects nucleic acids at ambient temperature [35] |

| Ideal For | Stabilizing tissue morphology; field collection; long-term archiving [33] | Difficult-to-lyse samples; simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA, and protein [34] | Sample collection in field; transport of infectious samples; stabilizing both DNA and RNA [35] |

| Sample Storage | 4°C (1 month), 25°C (1 week), -20°C (indefinitely) [33] | Homogenate can be stored at -80°C for long periods [36] | Room temperature for weeks [35] |

| Key Advantage | Preserves histology; no need for immediate freezing [33] | High yield and integrity; versatile for multiple sample types [34] | Room-temperature stabilization; safe for shipping [35] |

| Consideration | Tissue must be trimmed for penetration; may make homogenization harder [37] [36] | Toxic phenol; requires careful phase separation [34] [37] | Proprietary formulation; cost |

Stabilization and Storage of Extracellular Vesicle (EV) Samples

Within the context of long-term storage for research, preserving Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) presents unique challenges. EVs are sensitive to freezing and storage conditions, which can lead to aggregation, cargo loss, and reduced functionality [38] [39].

- Best Practices for EV Storage:

- Temperature: For long-term storage, -80°C is recommended [38].

- Buffer: Storing EVs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone can cause damage and particle loss. The use of specialized buffers is strongly advised [39].

- Stabilizing Additives: Adding cryoprotectants like trehalose and proteins like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or human serum albumin (HSA) to PBS-HEPES buffer has been shown to significantly improve the stability of EVs, protecting their physical integrity and cargo [39].

- Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles, as they decrease particle concentration, impair bioactivity, and cause aggregation [38].

- State of Isolation: Evidence suggests that storing EVs in their native biofluid offers more stability than storing them as purified isolates in buffer [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | An aqueous, non-toxic reagent for stabilizing and protecting RNA in fresh tissues and cells without immediate freezing [33]. |

| TRIzol Reagent | A mono-phasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for the effective lysis of samples and subsequent separation of RNA, DNA, and protein [34]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield (e.g., RNAprotect) | A reagent that immediately stabilizes nucleic acids at room temperature upon collection, inactivating nucleases and protecting against degradation [35]. |

| Chloroform | Used in conjunction with TRIzol for phase separation, partitioning DNA to the interphase and RNA to the aqueous phase [34]. |