Organic vs. Solid-Phase Nucleic Acid Extraction: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Diagnostics

This article provides a systematic comparison of organic (liquid-phase) and solid-phase nucleic acid extraction methods, crucial first steps in molecular biology and diagnostics.

Organic vs. Solid-Phase Nucleic Acid Extraction: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of organic (liquid-phase) and solid-phase nucleic acid extraction methods, crucial first steps in molecular biology and diagnostics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles, biochemical mechanisms, and practical applications of each technique. The scope ranges from foundational knowledge and detailed methodologies to troubleshooting common issues and presenting validation data from recent studies. By synthesizing performance metrics, cost-benefit analyses, and suitability for various sample types and downstream applications, this review serves as a definitive guide for selecting and optimizing nucleic acid extraction protocols to enhance the reliability and efficiency of biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

The Foundations of Nucleic Acid Extraction: Principles and Evolution of Methodologies

In the fields of molecular biology and analytical chemistry, the preparation of pure samples is a critical precursor to accurate analysis. Among the myriad of techniques available, organic extraction and solid-phase extraction (SPE) have emerged as fundamental methodologies for isolating target compounds from complex matrices [1] [2]. While both techniques aim to separate and concentrate analytes, they operate on divergent principles and offer distinct advantages and limitations. Organic extraction, often called liquid-liquid extraction, relies on the differential solubility of compounds in immiscible solvents [1]. In contrast, SPE utilizes affinity interactions between analytes and a solid sorbent material to achieve separation [2] [3]. The choice between these methods significantly impacts the efficiency, purity, and success of downstream applications, particularly in nucleic acid research and drug development. This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of these foundational techniques, examining their core principles, historical development, and practical implementation to inform researchers in selecting the most appropriate methodology for their specific applications.

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Organic Extraction

Organic extraction is a liquid-liquid separation technique that exploits the differential solubility of biological molecules in immiscible aqueous and organic phases [1]. The fundamental principle involves partitioning biomolecules between these phases based on their chemical properties. When an organic solvent is added to an aqueous biological sample, a biphasic system forms. During centrifugation, hydrophobic molecules such as proteins and lipids migrate to the organic phase, while hydrophilic nucleic acids remain in the aqueous phase [1].

The pH of the extraction buffer is a critical factor determining selectivity. For DNA extraction, neutral to slightly basic conditions (pH 7-8) are employed to ensure DNA partitions into the aqueous phase. Conversely, acidic conditions favor RNA retention in the aqueous phase while DNA moves to the organic interphase [1]. The phenol-chloroform mixture is the most common organic combination, where phenol denatures proteins, chloroform enhances phase separation and facilitates lipid partitioning, and isoamyl alcohol is often added to reduce foam formation and stabilize the interface [1]. Following phase separation, nucleic acids in the aqueous phase are typically precipitated using ethanol or isopropanol for subsequent purification and concentration.

Solid-Phase Extraction

Solid-phase extraction operates on chromatographic principles where analytes are separated based on their specific interactions with a solid sorbent material [2] [3]. The process involves passing a liquid sample through a sorbent-packed cartridge or disk, where target compounds are retained while matrix components pass through. Retained analytes are later eluted using an appropriate solvent [2].

SPE sorbents function through several primary retention mechanisms [3]:

- Non-polar interactions: Utilizing van der Waals forces between non-polar functional groups (C18, C8, phenyl) and hydrophobic analytes from polar matrices.

- Polar interactions: Employing dipole-dipole or hydrogen bonding with polar functional groups (diol, amino, cyano) for polar analyte retention from non-polar matrices.

- Ion-exchange: Leveraging electrostatic interactions between charged analytes and oppositely charged sorbent functional groups (cationic or anionic).

- Mixed-mode: Combining multiple mechanisms, typically hydrophobic and ion-exchange, for highly selective separations [3].

The SPE process follows a systematic sequence: sorbent conditioning to activate functional groups, sample loading, washing to remove impurities, and elution of purified analytes [2] [3]. This multi-step approach enables significant sample cleanup and concentration, making it particularly valuable for complex matrices.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Extraction Techniques

| Parameter | Organic Extraction | Solid-Phase Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Differential solubility partitioning | Affinity adsorption chromatography |

| Phase System | Liquid-Liquid | Solid-Liquid |

| Key Mechanisms | Hydrophobicity, solubility | Van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions |

| Critical Factors | pH, solvent polarity, centrifugation | Sorbent chemistry, solvent polarity, pH |

| Typical Format | Centrifuge tubes | Cartridges, disks, pipette tips |

| Phase Separation | Physical separation after centrifugation | Selective elution from solid matrix |

Historical Context and Development

Evolution of Organic Extraction

The development of organic extraction methodologies parallels advances in molecular biology throughout the 20th century. The technique gained prominence with the phenol-chloroform method becoming a standard laboratory procedure for nucleic acid purification [1]. This method established itself as a reliable approach for obtaining high-purity DNA and RNA, particularly for molecular cloning and early genomic studies. The introduction of specialized reagents like TRIzol, which combines phenol and guanidine thiocyanate in a monophasic solution, streamlined the simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA, and proteins from a single sample [1]. Despite the emergence of newer technologies, organic extraction remains valued for its effectiveness with challenging samples and cost-efficiency for processing large volumes.

Development of Solid-Phase Extraction

SPE has a more diverse technological evolution, with its first analytical applications emerging in the 1940s-1950s for analyzing organic traces in water samples [4]. Animal charcoal served as the earliest adsorbent for removing pigments from reaction mixtures [2]. The technique progressed through several distinct developmental phases [2] [4]:

The Age of Active Carbon (1950s-1960s): Early applications primarily utilized activated carbon for concentrating organic pollutants from water, though recovery was often problematic due to strong adsorption [4].

The Search for Appropriate Materials (1970s-1980s): Researchers investigated various synthetic polymers, including styrenedivinylbenzene resins, to overcome the limitations of carbon [2] [4]. The introduction of octadecyl silica (C18) bonded phases in the late 1970s marked a significant advancement, enabling more predictable reversed-phase interactions [2].

The Age of Technical Developments (1980s): This period saw the commercialization of pre-packed columns and cartridges, standardization of protocols, and theoretical modeling of SPE processes [4]. The introduction of SPE disks and membranes in 1989 provided greater cross-sectional areas for processing large sample volumes more efficiently [2].

Modern SPE continues to evolve with developments in monolithic sorbents, molecularly imprinted polymers, and various configurations including pipette-tip SPE for small volumes and 96-well plates for high-throughput applications [2].

Table 2: Historical Timeline of Extraction Method Development

| Time Period | Organic Extraction Milestones | Solid-Phase Extraction Milestones |

|---|---|---|

| 1940s-1950s | Early phenol-based methods | First SPE applications with active carbon |

| 1960s-1970s | Standardization of phenol-chloroform protocols | Development of synthetic polymer sorbents |

| 1970s-1980s | Adoption for molecular cloning | Introduction of bonded silica phases (C18) |

| 1980s-1990s | TRIzol and commercial reagent systems | Commercial pre-packed columns; SPE disks |

| 1990s-Present | Automation and safety improvements | Monolithic sorbents; high-throughput formats |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Method Comparison

Evaluating the performance characteristics of organic extraction and SPE reveals a clear trade-off between purity, efficiency, and practicality. The following table summarizes key performance metrics based on experimental data and technical specifications:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Organic vs. Solid-Phase Extraction

| Performance Parameter | Organic Extraction | Solid-Phase Extraction | Experimental Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Removal Efficiency | High (effective denaturation) | Variable (depends on sorbent) | Protein quantification post-extraction; SDS-PAGE |

| Nucleic Acid Yield | High for complex samples | High to moderate | Spectrophotometry (A260)/fluorometry |

| Typical Processing Time | 30-90 minutes | 15-45 minutes | Hands-on time for standard protocols |

| Detection Limits | Higher (ng/mL range) | Lower (0.1-1.0 ng/mL for SPME) | Analytical instrument detection limits [5] |

| Sample Volume Capacity | Flexible (μL to mL) | Cartridge-dependent (500μL-50mL) | Manufacturer specifications [2] |

| Risk of Emulsion Formation | Moderate to High | None | Observation during method development |

| Cross-Contamination Risk | Moderate (phase mixing) | Low with proper washing | PCR amplification of non-target sequences |

| Solvent Consumption | High (multiple volumes) | Low (focused elution) | Solvent volume per extraction |

Applications in Nucleic Acid Research

Both techniques have found specific niches in nucleic acid extraction workflows, each offering distinct advantages for particular applications:

Organic Extraction Applications:

- Genomic DNA extraction from complex tissues and biological samples [1]

- RNA purification for transcriptomic studies and RNA-seq applications [1]

- Plasmid isolation when high purity is required for cloning [1]

- Challenging samples with high lipid content or abundant proteins

Solid-Phase Extraction Applications:

- High-throughput processing using 96-well plate formats [2]

- Automated extraction systems for clinical and diagnostic testing [1]

- Environmental DNA analysis from water samples [4] [6]

- Forensic applications where sample integrity is critical [5]

- Selective isolation of specific nucleic acid types using functionalized sorbents

Experimental Protocols

Standard Organic Extraction Protocol for DNA

This protocol outlines the phenol-chloroform extraction method for DNA purification from biological samples [1]:

Reagents and Materials:

- Phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 ratio)

- Cell lysis buffer (e.g., containing SDS and proteinase K)

- Chloroform alone

- Ethanol (70% and absolute)

- Isopropanol

- TE buffer or nuclease-free water

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Refrigerated microcentrifuge

Methodology:

- Cell Lysis: Homogenize tissue or cell sample in appropriate lysis buffer. Incubate with proteinase K (if required) at 50-65°C until completely lysed.

- First Extraction: Add an equal volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol to the lysate. Mix thoroughly by inversion for 2-3 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Aqueous Phase Recovery: Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a fresh tube, avoiding the interphase and organic layer.

- Second Extraction: Add an equal volume of chloroform to the aqueous phase. Mix thoroughly and centrifuge as before.

- DNA Precipitation: Transfer the aqueous phase to a new tube. Add 0.5-1 volume of isopropanol or 2 volumes of cold ethanol. Mix by inversion until DNA precipitates.

- DNA Recovery: Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes. Carefully decant the supernatant.

- DNA Washing: Add 1 mL of 70% ethanol. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes. Carefully decant the ethanol.

- DNA Resuspension: Air-dry the pellet for 5-10 minutes (do not overdry). Resuspend in TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

Critical Steps:

- Maintain neutral pH (7-8) for DNA extraction

- Avoid transferring any organic phase during aqueous phase recovery

- Use wide-bore tips for pipetting high molecular weight DNA

- Ensure complete resuspension of the DNA pellet

Standard Solid-Phase Extraction Protocol for Nucleic Acids

This protocol describes SPE using silica-based membranes for nucleic acid purification [2] [3]:

Reagents and Materials:

- Silica-based SPE cartridge or spin column

- Cell lysis buffer (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride)

- Wash buffers (typically ethanol-based)

- Elution buffer (TE or nuclease-free water)

- Vacuum manifold or centrifuge

- Collection tubes

Methodology:

- Sorbent Conditioning: Apply 1-2 column volumes of conditioning solvent (e.g., methanol) to the sorbent bed. Follow with 1-2 column volumes of equilibration buffer (typically water or low-salt buffer).

- Sample Loading: Adjust sample conditions (e.g., add chaotropic salts) to promote nucleic acid binding. Apply sample to the conditioned sorbent under controlled flow rates (1-2 mL/min).

- Washing: Apply 2-3 column volumes of wash buffer (typically ethanol-based) to remove impurities. Ensure the sorbent does not dry completely between steps.

- Elution: Apply 1-2 column volumes of pre-warmed (65°C) elution buffer to the sorbent. Allow it to incubate for 1-2 minutes before applying pressure or centrifugation.

- Storage: Collect eluate containing purified nucleic acids. Store at appropriate temperatures for downstream applications.

Critical Steps:

- Do not let sorbent dry out before elution step

- Optimize flow rates for binding and washing steps

- Use pre-warmed elution buffer for higher yields

- Select appropriate sorbent chemistry for target nucleic acids

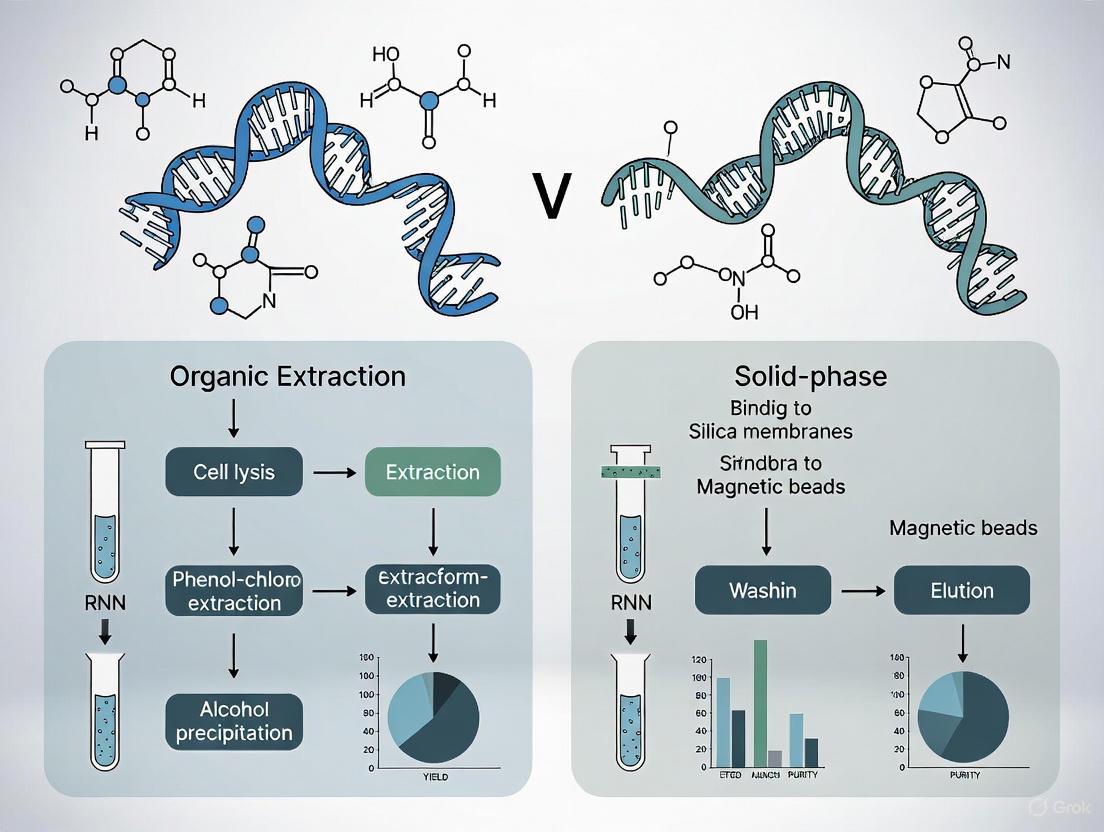

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of Organic and Solid-Phase Extraction Methods

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Extraction Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application in Organic Extraction | Application in SPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol | Protein denaturation | Essential for protein removal | Not typically used |

| Chloroform | Lipid solubilization, phase separation | Enhances protein partitioning | Not typically used |

| Isoamyl Alcohol | Foam reduction | Prevents emulsion formation | Not typically used |

| Silica Sorbents | Nucleic acid binding | Not typically used | Primary retention matrix |

| Chaotropic Salts | Nucleic acid binding promotion | Optional for precipitation | Essential for binding to silica |

| C18 Bonded Phase | Hydrophobic interactions | Not applicable | Reversed-phase extraction |

| Ion-Exchange Resins | Ionic interactions | Not applicable | Charged analyte retention |

| Ethanol/Isopropanol | Nucleic acid precipitation | Essential for precipitation | Wash buffer component |

| Guanidine Hydrochloride | Protein denaturation, nuclease inhibition | Optional in lysis buffers | Common in binding buffers |

| TE Buffer | Nucleic acid storage and elution | Resuspension buffer | Primary elution solution |

Organic extraction and solid-phase extraction represent two fundamentally different approaches to sample preparation, each with distinctive strengths and limitations. Organic extraction remains the gold standard for achieving high-purity nucleic acids from challenging samples, leveraging the proven efficacy of liquid-liquid partitioning [1]. Its disadvantages include labor-intensive procedures, use of hazardous solvents, and difficulty in automation. In contrast, SPE technologies offer faster processing, reduced solvent consumption, and excellent compatibility with automation and high-throughput workflows [2] [3].

The choice between these methodologies depends on multiple factors: the nature of the starting material, required purity levels, throughput needs, available resources, and safety considerations. For laboratories processing diverse sample types with varying requirements, maintaining expertise in both techniques provides the flexibility needed to address the broad spectrum of challenges encountered in modern nucleic acid research. As both technologies continue to evolve—with organic extraction focusing on safety improvements and SPE advancing through novel sorbent chemistries—researchers can expect continued enhancement in the efficiency and effectiveness of these fundamental sample preparation tools.

Nucleic acid extraction is a foundational technique in molecular biology, serving as a critical pre-analytical step for a vast array of applications from clinical diagnostics to advanced research. The efficacy of downstream processes, including PCR, sequencing, and microarray analysis, is profoundly dependent on the quality, purity, and yield of the isolated nucleic acids. The core principles of extraction, whether applied to DNA or RNA, revolve around four fundamental steps: lysis to disrupt cells and release nucleic acids, binding of the nucleic acids to a solid or liquid matrix, purification by removing contaminants and inhibitors, and concentration of the target nucleic acids into a small, usable volume. This guide delves into the specifics of these steps, providing a detailed comparison between the two predominant methodological philosophies: organic extraction and solid-phase extraction. By framing this within a broader thesis on extraction research, we will objectively compare product performance using supporting experimental data to inform the choices of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Core Principles: Four Fundamental Steps Explained

All nucleic acid extraction protocols, regardless of their specific chemistry, are built upon four essential stages. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key decisions at each step.

Step 1: Lysis

The first step involves breaking open the cell and nuclear membranes to release the nucleic acids into solution. Lysis must be efficient enough to access the genetic material without causing excessive degradation.

- Methods: Lysis can be achieved through chemical means (e.g., detergents, chaotropic salts, and enzymes like proteinase K) or mechanical means (e.g., bead-beating or homogenization) [7] [8]. The choice is sample-dependent; for instance, gram-positive bacteria or plant tissues with robust cell walls often require vigorous mechanical disruption in addition to chemical lysis [9] [8]. Chaotropic salts like guanidinium isothiocyanate not only aid in lysis but also denature proteins and protect nucleic acids from nucleases [10].

Step 2: Binding

Once released, the nucleic acids must be captured and separated from the lysate. This is the stage where the primary distinction between extraction methods emerges.

- Solid-Phase Binding: This method relies on the affinity of nucleic acids for a solid surface under specific conditions. In the presence of chaotropic salts, the negatively charged phosphate backbone of DNA and RNA binds to a silica matrix [7] [10]. This matrix can be formatted as a spin column membrane or as silica-coated magnetic beads.

- Liquid-Phase (Organic) Binding: In organic extraction, the lysate is mixed with phenol-chloroform. When centrifuged, the solution separates into an organic phase (containing denatured proteins and lipids), an interphase, and an aqueous phase where the nucleic acids reside [7] [11]. The binding here is not to a solid phase but a partition into the aqueous phase based on solubility.

Step 3: Purification (Washing)

The bound nucleic acids are associated with contaminants like proteins, salts, and other cellular debris that can inhibit downstream applications. The purification step removes these impurities.

- Solid-Phase Purification: The silica matrix is washed multiple times with ethanol-based buffers containing detergents or alcohols to remove contaminants while leaving the nucleic acids bound [7] [10].

- Liquid-Phase Purification: The aqueous phase containing the nucleic acids is carefully extracted from the phenol-chloroform mixture, physically separating it from the denatured proteins in the organic phase [11]. Further purification may involve additional chloroform extractions to remove residual phenol.

Step 4: Elution and Concentration

The final step is to recover the purified nucleic acids in a concentrated form suitable for analysis.

- Solid-Phase Elution: The nucleic acids are released from the silica matrix using a low-ionic-strength buffer like TE or nuclease-free water. The small volume of the elution buffer ensures the nucleic acids are concentrated [7] [12].

- Liquid-Phase Concentration: Nucleic acids in the aqueous phase are concentrated by precipitation, typically using isopropanol or ethanol in the presence of a salt like sodium acetate. The precipitated nucleic acid pellet is then washed with ethanol to remove residual salt and rehydrated in a small volume of buffer [7] [11].

Methodologies Compared: Organic vs. Solid-Phase Extraction

The choice between organic and solid-phase methods fundamentally shapes the extraction workflow, performance, and applicability. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Organic and Solid-Phase Extraction Methods

| Feature | Organic Extraction | Solid-Phase Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Liquid-liquid partitioning using phenol-chloroform [7] [11] | Binding to a solid silica matrix (columns or magnetic beads) [7] [10] |

| Typical Yield | High | Variable; can be very high with optimized methods (e.g., SHIFT-SP) [12] [10] |

| Purity | High, effective protein removal [11] | High, though may require thorough washing to remove chaotropes [10] |

| Throughput | Low, manual and labor-intensive [11] | High, easily automated [7] [13] |

| Automation | Difficult to automate [11] | Highly amenable to automation (liquid handlers, KingFisher systems) [13] [9] |

| Key Advantage | Considered a "gold standard"; effective on tough samples [11] | Safety, speed, and suitability for high-throughput workflows [7] |

| Key Disadvantage | Use of toxic, hazardous chemicals [7] [11] | Potential for low yield if binding is inefficient [11] |

Evolution of Solid-Phase Methods: Silica Columns and Magnetic Beads

Solid-phase extraction has become the dominant approach, particularly in clinical and high-throughput settings, and has evolved into two main formats.

Silica Spin Columns: In this format, the silica is embedded in a membrane within a plastic column. The lysate is passed through the membrane by centrifugation or vacuum, facilitating binding, washing, and elution in a self-contained unit [7] [11]. A limitation is that viscous samples or overloading can clog the membrane [11].

Magnetic Bead Technology: This method uses silica-coated paramagnetic beads. When an external magnetic field is applied, the beads (with bound nucleic acids) are immobilized, allowing the supernatant to be easily removed and exchanged for wash and elution buffers without centrifugation or vacuum filtration [7] [9]. This makes the process non-clogging and exceptionally well-suited for full automation [7] [9]. Recent research has focused on optimizing magnetic bead protocols to maximize speed and yield, as demonstrated by the SHIFT-SP method, which achieves extraction in 6-7 minutes with near-complete nucleic acid recovery [12] [10].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Theoretical advantages must be validated with experimental data. The following tables and experimental overviews provide a direct, objective comparison of extraction methodologies and systems.

Direct Method Comparison: Yield and Time

A 2025 study developed and benchmarked the SHIFT-SP method, a magnetic silica bead-based protocol, against other common commercial techniques, providing clear quantitative data on yield and processing time [12] [10].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Extraction Methods from a 2025 Study [12] [10]

| Extraction Method | Total Processing Time | Relative DNA Yield | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHIFT-SP (Magnetic Bead) | 6 - 7 minutes | ~100% | Optimized pH and tip-based mixing; automation-compatible. |

| Commercial Bead-Based | ~40 minutes | ~100% | Similar yield but significantly longer processing time. |

| Commercial Column-Based | ~25 minutes | ~50% | Faster than standard bead methods but half the yield. |

Experimental Protocol Summary [10]: The study optimized binding and elution conditions for a magnetic silica bead workflow. Key parameters included:

- Binding Buffer pH: Systematically compared pH 4.1 vs. 8.6, finding that a lower pH (4.1) reduced electrostatic repulsion between silica and DNA, increasing binding efficiency to 98.2% within 10 minutes.

- Mixing Mode: Compared orbital shaking to a pipette "tip-based" method (repeated aspiration/dispersion). Tip-based mixing achieved ~85% binding in 1 minute, a efficiency level that took 5 minutes with orbital shaking.

- Elution: Optimized temperature, duration, and buffer pH to maximize the recovery of bound nucleic acids.

Comparison of Automated Extraction Systems

Automation is key for standardizing high-throughput workflows. A 2024 study compared three automated nucleic acid extractors for processing complex human stool samples, a challenging matrix with diverse inhibitors and microbial cell types [9].

Table 3: Evaluation of Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Systems for Stool Samples [9]

| Extraction System | Technology Basis | Key Findings (Stool Samples) |

|---|---|---|

| KingFisher Apex | Magnetic bead-based | Effective recovery of Gram-positive bacteria; low inter-sample variability. |

| Maxwell RSC 16 | Magnetic bead-based / Cartridge-based | Robust performance; integrated system with pre-filled cartridges. |

| GenePure Pro | Magnetic bead-based | Comparable performance; differences in yield and variability observed. |

| All Automated Systems | - | Critical Finding: The inclusion of a bead-beating (mechanical lysis) step prior to automated extraction was essential for the effective lysis of Gram-positive bacteria and yielded a more representative microbial profile, regardless of the instrument used. |

Experimental Protocol Summary [9]: The study used triplicate fecal aliquots from healthy volunteers and a mock microbial community standard.

- Mechanical Lysis: Samples were homogenized using a FastPrep-24 bead-beating grinder at 6.0 m/s for 40 seconds.

- DNA Extraction & Quantification: Automated extraction was performed on each system according to manufacturer protocols. DNA was quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (for concentration) and a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (for purity).

- Downstream Analysis: 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing was performed to assess the impact of the extraction method on microbial community profiles (alpha- and beta-diversity).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents and kits is critical for success. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Item / Kit Name | Function / Application | Specific Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform | Organic extraction; partitions nucleic acids into aqueous phase while denaturing and removing proteins [7] [11]. | A standard, well-established protocol for high-purity isolation, though hazardous [11]. |

| Silica Spin Columns | Solid-phase extraction; membrane binds nucleic acids for in-column washing and elution [7]. | Used in commercial column-based kits compared in the 2025 study [10]. |

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Solid-phase extraction; beads bind nucleic acids for magnetic separation, enabling automation [7] [9]. | Core component of the SHIFT-SP method [10] and automated systems like KingFisher Apex and Maxwell RSC [9]. |

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCl) | Denature proteins, inactivate nucleases, and create conditions for nucleic acid binding to silica [7] [10]. | Key component of the Lysis Binding Buffer (LBB) in the VERSANT and SHIFT-SP protocols [10]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic lysis; digests proteins and helps to disrupt cellular structures [8]. | Commonly used in tissue lysis protocols to improve yield and purity [8]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield | Sample stabilization; prevents nucleic acid degradation during sample storage and transport [9]. | Used in the stool sample study to preserve integrity before extraction [9]. |

Practical Application and Workflow Selection

Translating experimental data into a practical laboratory decision requires considering sample type, downstream application, and operational needs. The following diagram outlines a decision pathway for selecting an extraction method.

Sample Type-Specific Considerations

- Challenging Matrices: For samples with complex compositions like stool, plants, or forensic swabs, specialized kits are essential. These kits often include additives like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to bind polyphenols from plants or enhanced wash buffers to remove PCR inhibitors like bile salts from stool [14] [8].

- Stabilized Samples: Samples stored in stabilization media (e.g., saliva, stool swabs) may yield less DNA per volume than raw samples, necessitating potential adjustments to input volume to meet the requirements of downstream assays [8].

- Forensic and Low-Input Samples: For challenging forensic applications like body fluid identification from saliva, the choice of extraction kit significantly impacts miRNA recovery and detection sensitivity, which is crucial for downstream RT-qPCR analysis [15]. Furthermore, high-yield methods like SHIFT-SP are particularly beneficial for low-concentration samples, such as microbes in enriched whole blood, enabling successful whole genome amplification and sequencing [10].

The fundamental steps of lysis, binding, purification, and elution/concentration form the unchanging backbone of nucleic acid extraction. However, the methodologies to execute these steps are constantly evolving. While organic extraction remains a powerful, gold-standard method for its purity and effectiveness on challenging samples, the trends in research and clinical practice are decisively shifting towards solid-phase techniques, particularly magnetic bead-based automation. The driving forces are clear: enhanced safety, greater throughput, reduced hands-on time, and improved reproducibility. As evidenced by recent studies, the optimization of solid-phase protocols is closing historical performance gaps, achieving speeds and yields that were previously unattainable. For the modern researcher, the optimal choice is not a matter of declaring one method the universal winner, but of strategically matching the method—be it organic, column-based, or magnetic bead-based—to the specific constraints of the sample, the application, and the operational environment.

This guide provides an objective comparison of nucleic acid isolation methods, focusing on the biochemical principles of chaotropic salt, pH, and silica interface techniques. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes experimental data to evaluate performance across key parameters including yield, purity, time, and cost, framed within the broader research context of organic versus solid-phase extraction methodologies.

Nucleic acid isolation relies on sophisticated biochemical interactions between chaotropic salts, silica surfaces, and nucleic acids at specific pH levels. Chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) and guanidine thiocyanate) function by disrupting the hydrogen-bonded network of water molecules, thereby solubilizing hydrophobic molecules and denaturing proteins that would otherwise interfere with nucleic acid purification. [16] [17] In the presence of these salts, nucleic acids lose their hydration shell and become susceptible to binding onto solid surfaces. The silica interface mechanism involves the adsorption of the negatively charged phosphate backbone of nucleic acids onto the positively charged silica surface, a process mediated by chaotropic salts acting as a cation bridge. [16] [18] The pH of the binding environment critically influences this interaction; a lower pH (e.g., pH 4.1) reduces the negative charge on both silica and DNA, minimizing electrostatic repulsion and significantly enhancing binding efficiency compared to neutral or alkaline conditions. [10] Understanding these intertwined mechanisms is essential for selecting and optimizing extraction methods for specific downstream applications.

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Methodologies

The following analysis compares three primary extraction methodologies: chaotropic salt/silica-based, magnetic nanoparticle, and organic extraction.

Performance Comparison Table

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Method Performance

| Extraction Method | Reported DNA Yield | Extraction Time | Cost per Sample (USD) | Suitability for Complex Samples | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts + Silica (SHIFT-SP) [10] | ~96% (1000 ng input) | 6-7 minutes | Medium (Kit-dependent) | High (Optimized for stool, blood) [16] [10] | High speed, high yield, automation-compatible |

| Magnetic Ionic Liquids (MILs) [18] | High (qPCR/LAMP compatible) | < 30 minutes | Low (Green synthesis) | High (Milk, plasma, plant tissue) [18] | Direct integration with amplification, minimal purification |

| Chelex 100 Resin [19] | Highest yield in comparison study | ~90 minutes | Very Low (33x cheaper than kits) [19] | Medium (Nasopharyngeal samples) [19] | Extreme cost-effectiveness, simple protocol, high yield |

| Phenol-Chloroform (Organic) [19] | Lower yield in comparison study | >2 hours | Low (13x cheaper than kits) [19] | High | Effective inhibitor removal, no size bias |

| Traditional Silica Columns [10] [20] | ~50% of input DNA [10] | ~25 minutes [10] | High [19] | Medium to High | Widespread use, good purity |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) [21] | High quality and quantity [21] | ~40 minutes [10] | Very Low [21] | High (Bacterial cells, blood serum) [21] | Cost-effective, easy manipulation, amenable to automation |

- Chaotropic Salt and Silica Optimization: A study optimizing a magnetic silica bead-based method (SHIFT-SP) demonstrated that binding buffer pH drastically affects efficiency. At pH 4.1, 98.2% of input DNA was bound to beads within 10 minutes, whereas only 84.3% was bound at pH 8.6. [10] The mode of bead mixing was also critical; a "tip-based" method achieved ~85% DNA binding in 1 minute, a significant improvement over orbital shaking. [10]

- Magnetic Ionic Liquids (MILs): MILs like [Ni(OIm)62+][NTf2-]2 interact with DNA via electrostatic, π-π stacking, and van der Waals forces. [18] They enable direct DNA extraction from complex matrices such as diluted human plasma and vitamin D milk, with subsequent integration into qPCR or LAMP assays without the need for separate DNA elution steps. One study detected E. coli at concentrations as low as 5.2 CFU mL⁻¹ in milk using a MIL-LAMP assay. [18]

- Cost and Efficiency of Alternative Methods: A comprehensive cost-analysis revealed that in-house MNP-based protocols can cost less than $0.19 per sample, compared to ~$1.34 for a commercial MNP-kit and ~$13.37 for a column-based kit. [21] Another independent comparison found the Chelex 100 method to be 33 times cheaper than a commercial QIAamp kit and 13 times cheaper than phenol-chloroform, while also providing the highest DNA yield. [19]

- Inhibitor Challenges with Silica Columns: Research indicates that some commercial silica columns can elute an unidentified substance that inhibits downstream enzymatic reactions like sequencing and digestion if the eluted DNA is not sufficiently diluted. [20] This highlights a potential limitation of some commercial solid-phase methods that may not be apparent in standard yield and purity measurements.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol is designed for the detection of Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance markers from stool specimens.

- Lysis Buffer: 2.5 M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl), 1% SDS, 40 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 8.0.

- Procedure:

- Lysis: Add 200 μL of stool sample to 500 μL of lysis buffer and 40 μL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL). Vortex and incubate at 65°C for 15 minutes.

- Binding: Add 200 μL of 100% isopropanol and 20 μL of silicon-hydroxyl magnetic beads (Si-OH MBs) to the lysate. Mix thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- Washing: Separate the beads on a magnetic rack and discard the supernatant.

- Wash 1: Wash with 700 μL of a solution containing 2.5 M GuHCl and 40% ethanol.

- Wash 2: Wash with 700 μL of 80% ethanol.

- Elution: Air-dry the magnetic beads and elute the purified nucleic acids in 50 μL of nuclease-free water.

- Key Parameters: The optimal concentration of GuHCl was found to be 2.5 M, and SDS at 1% provided the most efficient lysis and highest qPCR sensitivity. [16]

This novel method simultaneously removes proteins and precipitates DNA, addressing enzymatic inhibition from silica columns.

- Reagents: Chaotropic salt (e.g., 2.7 M Guanidine Hydrochloride or 1 M Guanidine Thiocyanate), precipitation agent (50% Isopropanol or 20% PEG-8000), and a protein dilution solution.

- Procedure:

- Precipitation: To the sample, add one volume of chaotropic salt solution and one volume of precipitation agent (e.g., isopropanol). Mix gently and incubate at room temperature for 2 minutes.

- Protein Dilution: Add one volume of protein dilution solution to further deactivate any residual proteins.

- Pellet Washing: Centrifuge to pellet the DNA. Carefully remove the supernatant and wash the pellet with 70% ethanol to remove residual salts.

- Resuspension: Air-dry the pellet and resuspend the DNA in water or TE buffer.

- Key Findings: This one-step precipitation method effectively eliminated proteinase K activity to undetectable levels and avoided the enzymatic inhibition observed with concentrated silica-column eluents. [20]

Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

Chaotropic Salt and Silica-Binding Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and biochemical environment involved in nucleic acid binding to silica in the presence of chaotropic salts.

Comparison of Major Extraction Workflows

This diagram contrasts the procedural steps and time investment of three primary extraction methodologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Nucleic Acid Extraction and Their Functions

| Reagent | Biochemical Function | Typical Working Concentration | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guanidine Hydrochloride (GuHCl) | Chaotropic agent; denatures proteins, facilitates NA binding to silica [16] [17] | 2.5 - 4 M [16] [20] | Concentration affects lysis efficiency and PCR compatibility [16] |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent; disrupts lipid membranes and solubilizes proteins [16] | 1% (w/v) [16] | Can inhibit PCR if not thoroughly removed [18] |

| Silica-coated Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase matrix for NA binding; enables magnetic separation [16] [10] | Varies by bead size/surface area | Binding efficiency is highly dependent on pH and mixing mode [10] |

| Sodium Acetate (NaOAc) | Source of cations (Na+); neutralizes DNA charge to facilitate alcohol precipitation [19] | 0.3 M (final concentration) | Standard for ethanol precipitation steps |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease; degrades nucleases and cellular proteins [19] | 0.2 - 1 mg/mL [16] [19] | Requires incubation at 56°C for optimal activity |

| Chelex 100 Resin | Chelating polymer; binds metal ions to inactivate nucleases [19] | 5-10% (w/v) suspension [19] | Fast, low-cost method; suitable for PCR but not for long-term DNA storage [19] |

| Magnetic Ionic Liquids (MILs) | Paramagnetic solvents; extract NA via multiple interactions, compatible with direct amplification [18] | Solvent phase in extraction | Enables direct integration with LAMP/qPCR, reducing hands-on time [18] |

Nucleic acid extraction is a foundational technique in molecular biology, serving as the critical first step for a vast array of applications from basic research to clinical diagnostics. The methods for isolating DNA and RNA have evolved significantly, driven by the competing demands for yield, purity, speed, safety, and scalability. This evolution represents a broad thesis in life sciences methodology: the transition from classic organic, solution-based chemistry to sophisticated solid-phase protocols. This guide objectively charts this historical progression, comparing the performance of phenol-chloroform extraction, silica spin columns, and magnetic beads through the lens of published experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their selection of purification technologies.

The Evolution of Extraction Technologies

The following timeline illustrates the key milestones in the development of mainstream nucleic acid extraction methods:

The core principle of nucleic acid extraction involves three key steps: cell disruption (lysis), separation/purification of nucleic acids from other cellular components, and concentration of the purified nucleic acids [22]. The methods discussed here diverge fundamentally in how they achieve the critical purification step.

Phenol-Chloroform Extraction (Organic Phase Separation)

This traditional method relies on liquid-phase separation to purify nucleic acids [23] [24]. In this process, a sample is mixed with TRIzol (containing phenol and guanidinium salts), which lyses cells and inactivates nucleases. The subsequent addition of chloroform and centrifugation creates distinct phases: RNA remains in the aqueous phase, proteins in the organic phase, and DNA at the interphase [23]. The desired nucleic acid is then carefully pipetted and concentrated via ethanol precipitation.

Silica Spin Column (Solid-Phase Extraction)

This method utilizes a silica membrane in a column format to bind nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts [23] [22]. The sample is first lysed, and the lysate is mixed with ethanol or isopropanol before being loaded onto the column. Under high-salt conditions, the negatively charged nucleic acid backbone binds to the silica membrane, while contaminants pass through. The membrane is washed, and pure nucleic acids are eluted in a low-salt buffer or water.

Magnetic Beads (Solid-Phase Extraction)

This is a modification of solid-phase extraction where silica-coated paramagnetic beads replace the column [23] [24]. After sample lysis, the magnetic beads are added, and nucleic acids bind to them in the presence of chaotropic salts and alcohol. A magnet is used to immobilize the beads, allowing the supernatant to be removed. The bead-bound nucleic acids are washed and then eluted.

Comparative Performance Data from Experimental Studies

Yield and Purity Across Sample Types

Table 1: Comparison of RNA Yield and Purity from Blood and Oral Swab Samples [25]

| Sample Type | Extraction Method | Average Yield (ng/μL) | Average Purity (A260/A280) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Modified Manual AGPC | Significantly Higher | Significantly Lower |

| Blood | QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit | Lower | Significantly Higher |

| Blood | OxGEn RNA Kit | Lower | Significantly Higher |

| Oral Swab | Modified Manual AGPC | Higher | Significantly Lower |

| Oral Swab | QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit | Lower | Higher |

| Oral Swab | OxGEn RNA Kit | Lower | Higher |

A 2023 comparative study on RNA extraction from healthy individuals found that a modified manual acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (AGPC) method yielded a significantly higher amount of RNA from blood samples compared to commercial silica column-based kits (QIAamp and OxGEn). However, the purity of the AGPC extracts was significantly lower, which could render them unsuitable for sensitive downstream applications [25]. For oral swabs, the manual AGPC method also had lower purity compared to the commercial kits [25].

Speed, Throughput, and Practical Application

Table 2: Processing Time and Throughput of Automated Nucleic Acid Extractors [26]

| Extractor (Method) | Throughput (Samples/Run) | Preparation Time (16 samples) | Processing Time (16 samples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioer GenePure Pro (Magnetic Beads) | 1-32 | ~25 min | ~35 min |

| Maxwell RSC 16 (Magnetic Beads) | 1-16 | ~35 min | ~42 min |

| KingFisher Apex (Magnetic Beads) | 1-96 | ~40 min | ~40 min |

| Manual Spin Column | Variable | N/A | ~100 min |

Magnetic bead-based systems offer substantial gains in speed and are easily automated. A 2024 evaluation of automated extractors showed processing times for 16 samples ranging from 35-42 minutes, significantly faster than manual column-based extraction, which took about 100 minutes [26]. Throughput varies by instrument, with some systems like the KingFisher Apex capable of processing 96 samples simultaneously [26]. Furthermore, a 2025 study reported a novel magnetic silica bead method (SHIFT-SP) that reduced the extraction time to just 6-7 minutes while achieving a similar or better yield than commercial bead and column-based methods [10].

Performance with Challenging and Degraded Samples

Table 3: DNA Extraction from Degraded Mammalian Museum Specimens [27]

| Extraction Method | Success Rate | Noted Advantages/Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Phenol/Chloroform | Successful | Overall successful isolation. |

| QIAamp (Spin Column) | Successful | Outperformed magnetic bead isolations in these sample types. |

| Zymo MagBead (Magnetic Beads) | Lower Performance | Undigested tissue particles interfered with magnetic separation. |

A 2022 study on degraded mammalian museum specimens (53-130 years old) found that statistical analysis revealed the extraction method itself only explained 5% of the observed variation in outcomes, while specimen age explained 29% [27]. When isolation was successful, all methods produced quantifiable DNA. However, Qiagen spin columns and phenol-chloroform isolation outperformed Zymo magnetic bead isolations for these specific challenging samples, as particles from difficult-to-lyse materials interfered with the magnetic bead workflow [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function |

|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidinium thiocyanate) | Denature proteins, inactivate nucleases, and facilitate binding of nucleic acids to silica [23] [10]. |

| Phenol-Chloroform | Organic solvent mixture used for liquid-liquid phase separation of nucleic acids from proteins and other cellular components [23] [24]. |

| Silica Membrane / Beads | Solid phase that binds nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts and high ionic strength [23] [22] [24]. |

| Magnetic Beads | Silica-coated paramagnetic particles allowing for magnetic separation instead of centrifugation [23] [24]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that digests and inactivates proteins and nucleases during the lysis step [27]. |

| Ethanol / Isopropanol | Used to precipitate nucleic acids from solution and in wash buffers to remove salts and other impurities [23] [28]. |

| Wash Buffer | Typically an ethanol-based solution used to remove contaminants while leaving nucleic acids bound to the silica matrix [23] [22]. |

| Elution Buffer | Low-salt aqueous solution (e.g., TE buffer, nuclease-free water) that disrupts the nucleic acid-silica interaction to release purified molecules [23] [22]. |

The historical progression from phenol-chloroform to silica columns and magnetic beads reflects the evolving needs of molecular biology. The choice of method is not a matter of identifying a single "best" technology, but rather of selecting the right tool for a specific application.

- Phenol-Chloroform remains valuable for its high yield and low cost, particularly when dealing with difficult samples or when budget is a primary constraint, provided that safety precautions are observed.

- Silica Spin Columns offer an excellent balance of speed, safety, purity, and convenience for routine, small-to-medium scale processing in most research laboratories.

- Magnetic Beads represent the forefront for high-throughput and automated applications, providing superior speed, scalability, and ease of integration into robotic liquid handling systems, which is critical for clinical diagnostics and large-scale genomic studies.

This comparison underscores the broader thesis that methodological advances in nucleic acid purification have consistently moved towards integrating greater simplicity, safety, and scalability without wholly abandoning the foundational principles of organic chemistry that made early genomics possible.

Protocols in Practice: A Detailed Guide to Organic and Solid-Phase Extraction Techniques

Nucleic acid extraction represents a critical first step in the NGS sample prep protocol and a wide array of molecular biology applications. Within this domain, organic extraction methods remain foundational techniques despite the proliferation of commercial solid-phase systems. This guide provides an objective comparison of two principal organic extraction protocols: the classic phenol-chloroform method and the acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (AGPC) approach. Framed within the broader thesis of organic versus solid-phase nucleic acid extraction research, we examine these methods through experimental data, protocol details, and practical considerations to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of appropriate extraction methodologies.

Methodological Foundations and Historical Context

The very first DNA isolation was performed in 1869 by Friedrich Miescher, who experimented with leucocytes from pus-infected bandages to isolate a novel molecule from cell nuclei [24]. Since this pioneering work, nucleic acid extraction techniques have evolved significantly. Organic extraction methods leverage the fundamental biochemical properties of nucleic acids, particularly their differential solubility in aqueous versus organic phases.

The phenol-chloroform method relies on a mixture of phenol, chloroform, and a small amount of isoamyl alcohol to separate DNA from proteins and lipids [24]. When added to a cell lysate, this mixture forms an emulsion that, upon centrifugation, separates into distinct phases with DNA partitioning into the upper aqueous layer due to its hydrophilic nature [24].

The acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (AGPC) extraction, originally devised by Chomczynski and Sacchi in 1987, represents a refinement specifically optimized for RNA isolation [29] [30]. This single-step method combines the denaturing power of guanidinium thiocyanate with the extraction efficiency of phenol-chloroform to rapidly isolate intact RNA while effectively inhibiting RNases [30].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Phenol-Chloroform DNA Extraction Protocol

The phenol-chloroform DNA purification method effectively removes proteins and lipids from nucleic acids through differential solubility in immiscible solvents [31]. Below is the detailed experimental protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the biological sample for complete cell lysis. For cells, resuspend in an appropriate volume of lysis buffer (e.g., TE buffer with SDS and proteinase K). For tissues, grind in liquid nitrogen before resuspending in lysis buffer [31].

- Cell Lysis: Incubate at 55°C for 1-2 hours or until the sample is completely lysed. Add proteinase K to the lysis buffer if necessary to facilitate protein digestion [31].

- Phenol-Chloroform Extraction: Add one volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 ratio) to the lysed sample. Vortex or shake thoroughly for approximately 20 seconds to form an emulsion [31].

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge at room temperature for 5 minutes at 16,000 × g. This results in distinct layers: a lower organic phase containing denatured proteins and lipids, an interface, and an upper aqueous phase containing DNA. Carefully remove the upper aqueous phase without disturbing the interface or organic phase [31].

- Ethanol Precipitation:

- Add 1 μL glycogen (20 μg/μL), 0.5× volume of 7.5 M NH₄OAc (ammonium acetate), and 2.5× volume of 100% ethanol to the aqueous phase [31].

- Place the tube at -20°C overnight or at -80°C for at least 1 hour to precipitate DNA [31].

- Centrifuge at 4°C for 30 minutes at 16,000 × g to pellet the DNA.

- Carefully remove the supernatant without disturbing the pellet.

- Wash the pellet with 150 μL of 70% ethanol, centrifuge again, and carefully remove the supernatant.

- Air-dry the pellet for 5-10 minutes at room temperature or use a SpeedVac concentrator for 2 minutes [31].

- DNA Resuspension: Resuspend the purified DNA pellet in 50-100 μL of TE buffer or nuclease-free water by pipetting up and down 30-40 times [31].

- Quality Assessment: Measure DNA concentration and purity using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) or by running an aliquot on an agarose gel [31].

Figure 1: Phenol-Chloroform DNA Extraction Workflow

Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform (AGPC) RNA Extraction Protocol

The AGPC method isolates RNA through phase separation under acidic conditions, which preferentially partitions RNA into the aqueous phase while DNA remains in the organic phase [29]. A modified manual AGPC protocol for blood and oral swab samples demonstrates the contemporary application of this method [25]:

- Sample Preparation and Lysis:

- For 200 μL of blood sample, add 925 μL of 1X RBC lysis buffer and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes [25].

- Centrifuge at 1400 rpm for 10 minutes at 25°C. Discard the supernatant [25].

- Add 1000 μL of 1X RBC lysis buffer to the residue, incubate for 5 minutes at 25°C, then centrifuge at 3000 rpm for 2 minutes [25].

- Wash with 1000 μL of DPBS and centrifuge at 3000 rpm for 2 minutes. Discard the supernatant [25].

- Acid-Guadinidium Thiocyanate-Phenol Extraction:

- Add 1200 μL of homemade TRIzol reagent (containing water-saturated phenol, glycerol, sodium acetate, guanidine thiocyanate, and ammonium thiocyanate) to the residue to resuspend the cells [25].

- Add 200 μL of chloroform and vortex for 15 seconds [25].

- Centrifuge at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. This results in phase separation with RNA in the upper aqueous phase [25].

- RNA Precipitation:

- RNA Wash:

- RNA Elution:

- Quality Assessment: Quantify RNA using spectrophotometry and confirm integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis [25].

Figure 2: AGPC RNA Extraction Workflow

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Extraction Methods

The following tables summarize experimental data comparing the performance of organic extraction methods with solid-phase alternatives across different sample types and metrics.

Table 1: Performance comparison of DNA extraction methods from degraded human remains (n=25 samples) [32]

| Extraction Method | Small Human Target Quantity | Large Human Target Quantity | Degradation Index | Number of Reportable Loci | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic (Phenol-Chloroform) | Highest recovery | Superior recovery | Most favorable | Highest allele count | Best performing |

| Silica in Suspension | Good recovery | Good recovery | Favorable | Good allele count | Good performance |

| High Pure Silica Columns | Moderate recovery | Moderate recovery | Moderate | Moderate allele count | Moderate performance |

| InnoXtract Bone | Moderate recovery | Moderate recovery | Moderate | Moderate allele count | Moderate performance |

| PrepFiler BTA (Automated) | Moderate recovery | Moderate recovery | Moderate | Moderate allele count | Moderate performance |

Table 2: RNA extraction comparison between manual AGPC and commercial kits from blood and oral swabs (n=25 healthy individuals) [25]

| Extraction Method | Sample Type | Yield (ng/μL) | Purity (260/280 nm) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual AGPC | Blood | Highest | Lower | p < 0.0001 |

| Manual AGPC | Oral Swab | Highest | Lower | p < 0.0001 (vs QIAamp), p < 0.001 (vs OxGEn) |

| QIAamp Kit | Blood | Lower | Higher | p < 0.0001 |

| QIAamp Kit | Oral Swab | Lower | Higher | p < 0.0001 |

| OxGEn Kit | Blood | Lower | Higher | p < 0.0001 |

| OxGEn Kit | Oral Swab | Lower | Higher | p < 0.001 |

Table 3: Technical comparison of nucleic acid extraction methods [24] [11]

| Parameter | Phenol-Chloroform | AGPC | Silica Spin Columns | Magnetic Beads |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Yield | High | Very High | Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Purity | Good | Good for RNA | High | High |

| Processing Time | Long (several hours) | Moderate (4h to completion) | Short (25 min) | Very Short (6-7 min) |

| Cost Efficiency | High | High | Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Hazardous Materials | Yes (phenol, chloroform) | Yes (phenol, chloroform) | Minimal | Minimal |

| Automation Potential | Low | Low | Moderate | High |

| Throughput Capacity | Low | Low | High | Very High |

| Suitability for Small RNAs | Limited | Excellent | Poor (<200 nucleotides) | Good |

Key Experimental Findings

DNA Recovery from Challenging Samples: Organic extraction by phenol-chloroform/isoamyl alcohol demonstrated superior performance in forensic applications involving degraded skeletal remains, outperforming four other methods including silica-based approaches in both quantification metrics and DNA profile results [32].

RNA Yield Versus Purity Trade-off: The manual AGPC method showed significantly higher RNA yields from both blood and oral swab samples compared to commercial kits (p < 0.0001), but with correspondingly lower purity metrics [25]. This suggests a trade-off between quantity and quality that researchers must consider based on their downstream applications.

Efficiency in Modern Implementations: Recent innovations in magnetic silica bead-based extraction have achieved remarkable efficiency, with one method (SHIFT-SP) extracting nearly all nucleic acid from samples in just 6-7 minutes while maintaining compatibility with both DNA and RNA [10].

pH Optimization for Binding: Research on magnetic silica bead systems demonstrates that lower pH (4.1) significantly enhances nucleic acid binding efficiency, achieving 98.2% of input DNA bound within 10 minutes compared to 84.3% at pH 8.6 [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key reagents for organic nucleic acid extraction protocols

| Reagent | Function | Protocol Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Phenol | Denatures and extracts proteins; carboxic acid that is flammable, corrosive, and toxic [24] | Common to both protocols |

| Chloroform | Extracts lipids; enhances phase separation [31] [29] | Common to both protocols |

| Isoamyl Alcohol | Reduces foaming during extraction [29] | Common to both protocols |

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate | Chaotropic agent that denatures proteins, inactivates RNases [29] | AGPC-specific |

| Sodium Acetate (pH 5.0) | Provides acidic conditions for RNA partitioning [29] | AGPC-specific |

| Proteinase K | Digests and inactivates cellular nucleases [31] | Phenol-chloroform specific |

| Glycogen | Carrier for nucleic acid precipitation [31] | Common to both protocols |

| Ammonium Acetate | Salt for ethanol precipitation [31] | Phenol-chloroform specific |

| Isopropanol | Precipitates nucleic acids [29] [25] | AGPC-specific |

| Ethanol | Precipitates and washes nucleic acids [31] | Common to both protocols |

Discussion: Organic vs. Solid-Phase Extraction in Contemporary Research

Advantages and Limitations in Practice

Organic extraction methods offer distinct advantages that maintain their relevance in modern laboratories:

- Cost-Effectiveness: Both phenol-chloroform and AGPC methods are relatively inexpensive compared to commercial kits, making them preferable for resource-limited settings [31] [25].

- Recovery Efficiency: Organic extraction consistently demonstrates superior recovery of nucleic acids from challenging, degraded samples as evidenced by forensic applications [32].

- RNA Integrity: The AGPC method provides higher purity RNA recovery and better preserves short RNA species (<200 nucleotides) such as siRNA, miRNA, and tRNA that may be lost in column-based systems [29].

However, these methods present significant limitations:

- Labor Intensity: Both protocols are manual, laborious processes with multiple steps requiring careful handling [31].

- Safety Concerns: Phenol and chloroform are hazardous, toxic materials requiring special handling and disposal considerations [11].

- Throughput Constraints: Organic methods are not amenable to high-throughput processing or automation, limiting their utility in large-scale studies [11].

Method Selection Guidelines

The choice between organic and solid-phase extraction methods depends on specific research requirements:

- For Maximum Yield and Cost-Effectiveness: Organic methods, particularly AGPC for RNA, deliver superior recovery at lower cost [25].

- For High-Throughput Applications: Magnetic bead-based systems offer rapid processing (as little as 6-7 minutes) and excellent automation compatibility [10].

- For Challenging or Degraded Samples: Phenol-chloroform extraction outperforms solid-phase methods for forensic and ancient DNA applications [32].

- For Short RNA Species: AGPC remains the method of choice for miRNA, siRNA, and tRNA studies where column-based systems fail [29].

- For Routine Applications: Silica spin columns provide a balance of convenience, purity, and adequate yield for standard molecular biology workflows [11].

Organic extraction methods, particularly phenol-chloroform and AGPC protocols, continue to hold significant value in molecular biology despite the proliferation of solid-phase alternatives. The experimental data presented demonstrates that organic methods consistently achieve higher nucleic acid yields, particularly from challenging or degraded samples, while remaining cost-effective. However, this advantage comes with trade-offs in throughput, safety, and purity that researchers must carefully evaluate based on their specific applications, sample types, and available resources. As nucleic acid extraction technologies evolve, the integration of organic chemistry principles with solid-phase convenience—exemplified by modern magnetic bead systems—promises to further blur these methodological boundaries, ultimately providing researchers with an expanding toolkit for nucleic acid purification across diverse research and diagnostic applications.

Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) remains a cornerstone technique in analytical laboratories, serving as a critical sample preparation step across diverse fields including pharmaceuticals, environmental testing, food safety, and clinical diagnostics [33]. The fundamental principle of SPE involves selectively retaining target analytes on a solid sorbent while removing interfering matrix components, thereby purifying and concentrating samples for subsequent analysis. As analytical demands have evolved, so too have SPE technologies, with three primary formats emerging as dominant: silica spin columns, microplates, and magnetic bead technology. Within the specific context of nucleic acid extraction research, these SPE variants facilitate the isolation of DNA and RNA from complex biological matrices, enabling downstream applications from basic PCR to advanced next-generation sequencing [34] [35]. The choice between these methodologies significantly impacts not only workflow efficiency and cost, but also data quality and experimental outcomes, making a comprehensive comparative understanding essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Silica Spin Columns

Spin columns represent the traditional workhorse of nucleic acid extraction, operating on the principle of selective binding to a silica membrane under high-salt conditions [34]. The process involves sequential centrifugation steps: cellular lysis to release nucleic acids, binding to the silica membrane in the presence of chaotropic salts, washing to remove contaminants, and final elution in a low-salt buffer or water [11] [34]. Their simplicity and minimal equipment requirements (only a standard microcentrifuge) make them widely accessible [36]. However, their design presents inherent limitations for high-throughput applications, as they are inherently single-tube formats with limited automation compatibility [37].

Microplates

Microplate-based SPE systems represent a scalable adaptation of the spin column principle, utilizing 96-well plates containing silica or other functionalized sorbents [38]. Processing typically employs vacuum manifolds or centrifugation systems capable of handling all wells simultaneously, offering a significant throughput advantage over individual spin columns [11]. This format is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical and clinical settings where processing hundreds of samples is routine. While more efficient than single columns, microplates still face challenges related to potential membrane clogging and can require substantial manual liquid handling unless integrated with robotic systems [11].

Magnetic Bead Technology

Magnetic bead technology, a more recent innovation, utilizes paramagnetic particles coated with a silica or other functionalized surface that binds nucleic acids reversibly [11] [35]. The core mechanism, known as Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI), occurs in the presence of polyethylene glycol (PEG) and salt [37]. The magnetic property of the beads enables separation using a magnetic field, eliminating the need for centrifugation or vacuum filtration [37] [35]. This fundamental difference facilitates seamless automation, as beads can be moved through wash steps while immobilized, making the technology ideal for high-throughput workflows and integration with liquid handling robots [37] [36]. A key advantage is the ease of scaling reactions by simply adjusting bead-to-sample ratios, which also allows for flexible size selection of nucleic acids [37].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Direct comparisons between these technologies reveal significant differences in performance characteristics, influencing their suitability for specific applications.

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of SPE Variants

| Performance Characteristic | Silica Spin Columns | Microplates | Magnetic Beads |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery Yield | 70-85% [37] | Similar to spin columns | 94-96% [37] |

| DNA Size Range | 100 bp – 10 kb [37] | Similar to spin columns | 100 bp – 50 kb [37] |

| Throughput Capacity | Low (manual, single-tube) [37] [36] | High (96-well batch processing) [11] | High (96/384-well & full automation) [37] [36] |

| Automation Compatibility | No [37] | Limited (vacuum/centrifuge systems) [11] | Yes (full robotic integration) [37] [36] |

| Hands-on Time | Manual, per sample [36] | Moderate (batch processing) | Minimal (no centrifugation) [36] |

| Size Selection Capability | No [37] | Limited | Yes (via adjustable bead ratio) [37] |

| Cost per Sample | ~$1.75 [37] | Moderate | ~$0.90 [37] |

Application-Specific Performance Data

Experimental data from direct comparisons further illuminates the performance differences. A 2025 clinical study comparing boiling (a simple lysis method) versus magnetic bead extraction for HPV genotyping detection demonstrated the superior performance of magnetic bead technology. The positive detection rate for HPV using the magnetic bead method was 20.66%, significantly higher than the 10.02% achieved with the boiling method (P < 0.001) in a paired study of 639 specimens [39]. Furthermore, the magnetic bead method exhibited superior resistance to inhibitors like hemoglobin, maintaining detection even at 60 g/L hemoglobin concentration, whereas the simple method failed at 30 g/L [39]. Although this cost 13.14% more, it increased the detection rate by 106.19%, demonstrating excellent cost-effectiveness for clinical diagnostics [39].

For nucleic acid purification, magnetic bead systems like the HighPrep PCR Cleanup Kit demonstrate superior recovery rates of 94-96% compared to 70-85% for spin columns, with the additional advantage of fragment size selection by modulating the bead-to-sample ratio [37].

Table 2: Fragment Size Selection in Magnetic Bead-Based Purification

| Bead-to-Sample Ratio | DNA Fragment Size Retained |

|---|---|

| 0.6x | >500 bp |

| 0.8x | >300 bp |

| 1.0x | >100 bp |

| 1.8x | >50 bp |

Source: Adapted from MagBio Genomics HighPrep protocol [37]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Nucleic Acid Extraction via Magnetic Bead Technology

The following protocol, adapted from the NAxtra magnetic nanoparticle procedure [35] and HighPrep methodologies [37], outlines a standardized approach for automated nucleic acid extraction suitable for high-throughput applications.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Lysis buffer (e.g., customized buffer with RNase inhibitors) [35]

- Magnetic beads (e.g., silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles) [35]

- Wash buffers (typically ethanol-based) [37]

- Elution buffer (nuclease-free water or TE buffer) [37]

- KingFisher Flex Purification System or equivalent magnetic particle processor [35]

- 96-well deep-well plates

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Transfer 300 µL of sample to a 96-well deep-well plate. Add lysis buffer and mix thoroughly to release nucleic acids. Incubate for 5-10 minutes at room temperature [35].

- Binding: Add 1.8x volume of magnetic beads to the lysate. Mix thoroughly by pipetting or plate shaking. Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature to allow nucleic acid binding [37].

- Separation: Transfer the plate to the magnetic processor. Engage the magnetic field for 2-5 minutes until beads form a pellet and the supernatant clears [37].

- Washing: Remove and discard the supernatant while maintaining the magnetic field. Add 200 µL of 80% ethanol wash buffer. Incubate for 30 seconds, then remove the wash solution. Repeat this wash step twice [37] [35].

- Drying: Air-dry the bead pellet for 3-5 minutes at room temperature to ensure complete ethanol evaporation. Avoid over-drying, which can reduce elution efficiency [37].

- Elution: Remove the plate from the magnetic field. Add 20-50 µL of nuclease-free water or elution buffer. Mix thoroughly and incubate for 2-5 minutes to resuspend beads and release nucleic acids [37].

- Final Separation: Return the plate to the magnetic field for 2 minutes. Transfer the clarified eluate containing purified nucleic acids to a clean collection plate [35].

Typical Duration: 12-18 minutes for 96 samples when automated [35].

Protocol: Solid-Phase Extraction for Pharmaceutical Compounds

This protocol, adapted from wastewater pharmaceutical analysis research [40], demonstrates the application of cartridge-based SPE for small molecule extraction, highlighting its relevance in environmental and pharmaceutical analysis.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Oasis HLB cartridges (60 mg/3 mL) or equivalent [40]

- Vacuum manifold

- Methanol (HPLC grade)

- Acidified water (pH 2 with HCl) [40]

- Nitrogen evaporator

Procedure:

- Conditioning: Pre-condition the HLB cartridge with 5 mL of methanol, followed by 5 mL of acidified water (pH 2) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min [40].

- Sample Loading: Load 100 mL of sample (adjusted to pH 2) onto the cartridge under vacuum [40].

- Washing: Rinse the cartridge with 5 mL of 10% methanol and 5 mL of ultra-pure water to remove interfering compounds [40].

- Elution: Elute the adsorbed analytes with 4-6 mL of 100% methanol into a collection tube [40].

- Concentration: Evaporate the eluate to dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream at 50°C. Reconstitute the residue in 1 mL of methanol [40].

- Filtration: Filter the reconstituted sample through a 0.22 µm nylon syringe filter prior to HPLC analysis [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Solid-Phase Extraction Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance (HLB) Cartridges | Retains both polar and non-polar compounds [40] | Pharmaceutical contaminant extraction from wastewater [40] |

| Silica-Coated Magnetic Beads | Paramagnetic particles with silica surface for nucleic acid binding [35] | High-throughput DNA/RNA extraction [37] [35] |

| Chaotropic Salts | Denature proteins and promote nucleic acid binding to silica [11] | Spin column nucleic acid purification [11] [34] |

| ENV+ and PHE SPE Sorbents | Specialized sorbents for multiplexed extraction of diverse analytes [41] | Untargeted adductomics from urine samples [41] |

| PCR Cleanup Magnetic Beads | Size-selective binding of nucleic acids via SPRI technology [37] | Post-amplification purification and size selection [37] |

Selection Guidelines and Future Perspectives

Technology Selection Framework

Choosing the appropriate SPE technology requires careful consideration of application requirements and laboratory constraints:

- Choose Silica Spin Columns when: Processing small sample numbers (1-24), working with limited budget, operating in minimally equipped laboratories, or when method development time is limited [34] [36].

- Choose Microplate Formats when: Processing medium to high sample volumes (96-384), utilizing vacuum manifold systems, and when consistent batch processing is prioritized [38].

- Choose Magnetic Bead Technology when: Throughput and automation are critical, working with challenging samples (low concentration/inhibitors), requiring high recovery yields, needing size selection capability, or when minimizing hands-on time is a priority [37] [36] [35].

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The SPE landscape continues to evolve, with several key trends shaping its trajectory. By 2025, vendors are prioritizing automation, miniaturization, and environmentally sustainable solutions [33]. The integration of SPE with other analytical techniques, particularly online SPE-LC-MS systems, is creating streamlined workflows that enhance analytical efficiency and reduce manual intervention [38]. The development of novel sorbent materials with improved selectivity continues to expand application possibilities, while the push toward miniaturization through microfluidic devices reduces solvent consumption and sample volume requirements [38]. These advancements, coupled with growing demand in pharmaceutical and environmental sectors, project a market value exceeding $900 million by 2033, with magnetic bead technology and automated systems expected to capture increasing market share [38].

In molecular research, the purity and integrity of isolated nucleic acids are foundational to the success of downstream applications, from routine PCR to cutting-edge next-generation sequencing. The choice of extraction method is a critical decision point that balances yield, purity, scalability, and safety. This guide objectively compares the two predominant philosophies in nucleic acid isolation: organic extraction and solid-phase extraction, with a focus on tailoring these methods to specific sample types including blood, stool, tissues, and cultured cells. Organic extraction, historically the gold standard, relies on liquid-phase separation using phenol-chloroform, while solid-phase methods utilize a solid substrate, most commonly silica, to bind and purify nucleic acids [11]. The following sections provide a detailed comparison based on experimental data, outline sample-specific optimized protocols, and present key reagent solutions to equip researchers with the tools for informed methodological selection.

Method Comparison: Organic vs. Solid-Phase Extraction

The performance of any extraction method is quantified through metrics such as nucleic acid yield, purity, processing time, and suitability for automation. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the primary extraction techniques.