Optimizing Nucleic Acid Extraction: A Comprehensive Guide to Maximizing Yield, Purity, and Downstream Success

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing nucleic acid extraction, a critical first step in molecular biology and diagnostic workflows.

Optimizing Nucleic Acid Extraction: A Comprehensive Guide to Maximizing Yield, Purity, and Downstream Success

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing nucleic acid extraction, a critical first step in molecular biology and diagnostic workflows. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details core methodologies from traditional phenol-chloroform to modern magnetic bead-based automated systems. The content offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common issues like low yield, contamination, and inhibitor removal, and presents a rigorous comparative analysis of extraction techniques based on recent, large-scale clinical evidence. The goal is to empower scientists with the knowledge to select, optimize, and validate extraction protocols that ensure high-quality nucleic acids for sensitive downstream applications like PCR, sequencing, and clinical diagnostics.

The Building Blocks of Success: Core Principles of Nucleic Acid Extraction

Why Yield and Purity are Non-Negotiable for Downstream Applications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the key indicators of DNA and RNA purity, and what are their acceptable ranges? Purity is typically assessed using absorbance ratios measured by a spectrophotometer. For DNA, an A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8 and an A260/A230 ratio of 2.0–2.2 are generally accepted as pure. For RNA, the acceptable A260/A280 ratio is typically 1.8–2.2 [1] [2] [3]. A lower A260/A280 ratio may indicate protein or phenol contamination, while a lower A260/230 ratio suggests the presence of contaminants like salts, carbohydrates, or guanidine [1] [2].

2. Why is assessing both yield and purity crucial before expensive downstream applications? Overlooking DNA yield and purity assessment is a common source of troubleshooting in experiments like PCR and sequencing [4]. Impure or incorrectly quantified DNA can lead to:

- Low-confidence results and failed experiments.

- High costs associated with repeating assays.

- Waste of precious samples that may be irreplaceable [1] [4]. Ensuring high quality prevents these issues and guarantees the reproducibility and accuracy of your research.

3. My DNA has a good A260/A280 ratio but my downstream applications are failing. What could be wrong? The A260/A280 ratio does not provide information about DNA integrity (the size and fragmentation of the nucleic acid strands) [1]. Degraded DNA, which appears as a smear on a gel instead of a tight high-molecular-weight band, can cause failures in applications like long-read sequencing or PCR [1] [3]. It is essential to use methods like agarose gel electrophoresis or instruments like the Bioanalyzer to confirm DNA integrity.

4. How does the source of my biological sample impact the quality of the extracted nucleic acid? The sample source greatly influences the quality and suitability of the DNA for different applications.

- Frozen blood is a prospective collection option that provides high-quality DNA [1].

- Frozen tissue is recommended when diseased tissue is a requisite for the study [1].

- Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues typically yield more degraded and lower-quality DNA compared to frozen tissues [1].

5. What is the difference between spectrophotometry and fluorometry for quantifying nucleic acids? These two methods provide different information and should be used complementarily.

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Quantification Methods

| Feature | Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) | Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit with Assay Kits) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measures absorbance of UV light | Fluorescence of dye that binds specifically to nucleic acids |

| Measures | Total nucleic acids (dsDNA, ssDNA, RNA) | Specific nucleic acid type (e.g., dsDNA, RNA) |

| Purity Info | Yes (via A260/A280 & A260/230 ratios) | No |

| Sensitivity | Lower (e.g., 2-5 ng/µL) | Higher (e.g., pg/µL levels) [2] |

| Key Advantage | Fast, requires small volume, assesses purity | Highly specific and accurate for concentration |

For optimal results, use fluorometry for accurate concentration measurement and spectrophotometry for purity assessment [1] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Purity (Contaminated Nucleic Acid Sample)

Low purity ratios indicate the presence of contaminants that can inhibit enzymatic reactions in downstream applications.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Purity Absorbance Ratios

| Symptom | Potential Contaminant | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low A260/A280 (≤1.6) | Protein or Phenol | • Use additional purification steps (e.g., silica column clean-up) [1]. • Ensure complete removal of organic phases during extraction. |

| High A260/A280 (>1.8 for DNA) | RNA in DNA sample | • Treat DNA sample with RNase A [5]. |

| Low A260/A230 (<<2.0) | Salts, EDTA, carbohydrates, or guanidine | • Perform an ethanol precipitation with a final 70% ethanol wash [1] [2]. • Ensure the elution buffer used is of low-ionic strength (e.g., Tris-HCl, TE buffer) and not water, which can affect the ratio [1]. |

Problem: Low Yield or Degraded Nucleic Acids

Low Yield:

- Cause: Inefficient binding during extraction, over-dilution, or using a sample with low starting material.

- Solutions:

- Optimize binding conditions: For silica-based methods, ensure a high concentration of chaotropic salt and the correct pH. One study showed shifting binding buffer pH from 8.6 to 4.1 increased DNA binding efficiency from 84.3% to 98.2% [6].

- Increase input material: If possible, start with more biological material.

- Use carrier RNA: For very low concentration samples, carrier RNA can help improve recovery in some extraction protocols.

Degraded Nucleic Acids:

- Cause: RNase contamination (for RNA) or physical shearing and nuclease activity (for DNA).

- Solutions:

- Use nuclease-free reagents and consumables.

- Handle samples gently: Avoid vortexing or pipetting high-molecular-weight DNA vigorously [3].

- Store properly: For long-term storage of DNA, use TE buffer and store at -20°C or -80°C [3].

- Work quickly and on ice: Keep samples cold to slow nuclease activity.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing DNA/RNA Purity and Concentration using Spectrophotometry

This protocol is for instruments like the NanoDrop.

- Blank the instrument using the same elution buffer your nucleic acid is dissolved in (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water).

- Apply 1-2 µL of your sample to the measurement pedestal.

- Record the following values:

- Concentration (ng/µL): Provided by the instrument based on A260.

- A260/A280 Ratio: Target ~1.8 for DNA, 1.8-2.2 for RNA.

- A260/230 Ratio: Target 2.0-2.2 for both.

- Interpret results and proceed with purification if ratios are outside the acceptable range (refer to Table 2).

Protocol 2: Assessing Nucleic Acid Integrity by Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

This method visually confirms the size and integrity of your DNA.

- Prepare a 0.8%-1% agarose gel in 1X TAE or TBE buffer, stained with a fluorescent nucleic acid dye (e.g., GelRed, SYBR Safe).

- Mix a volume of your DNA sample (e.g., 50-100 ng) with a DNA loading dye.

- Load the mixture into the gel well alongside a DNA molecular weight marker (ladder).

- Run the gel at 5-8 V/cm until bands have adequately separated.

- Visualize under UV light.

- Interpret results: High-quality genomic DNA should appear as a single, tight high-molecular-weight band. A smear indicates degradation. RNA samples should show sharp ribosomal RNA bands (28S and 18S for eukaryotic RNA) with a 2:1 intensity ratio [1] [2].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in the nucleic acid quality control workflow.

Nucleic Acid Quality Control Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Nucleic Acid QC

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Qubit Fluorometer & dsDNA BR Assay | Provides highly specific and sensitive quantification of dsDNA concentration, unaffected by contaminants like RNA or salts [3]. |

| NanoDrop Spectrophotometer | Rapidly assesses nucleic acid concentration and purity (A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios) using only 1-2 µL of sample [2]. |

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Provides a highly sensitive, automated, and quantitative assessment of nucleic acid integrity and size, similar to a digital gel [2] [3]. |

| Silica-Membrane Spin Columns | Standard solid-phase extraction method for purifying nucleic acids, effectively removing contaminants and yielding high-purity eluates [5]. |

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Enable automated, high-throughput nucleic acid extraction with efficient binding and washing, ideal for processing many samples [1] [6]. |

| PicoGreen dsDNA Quantification Reagent | A fluorometric dye used in plate readers for highly sensitive detection of dsDNA, minimizing contributions from RNA and ssDNA [1]. |

This technical support center guide is framed within a broader thesis on optimizing nucleic acid extraction, a critical upstream process that fundamentally impacts the success and accuracy of downstream molecular analyses in research and drug development [6] [7]. The universal four-step process—Lysis, Binding (Purification), Wash, and Elution—forms the foundation of most modern solid-phase extraction methods. This guide provides detailed troubleshooting FAQs and experimental protocols to help researchers maximize nucleic acid yield and purity, thereby enhancing the reliability of applications from PCR to next-generation sequencing.

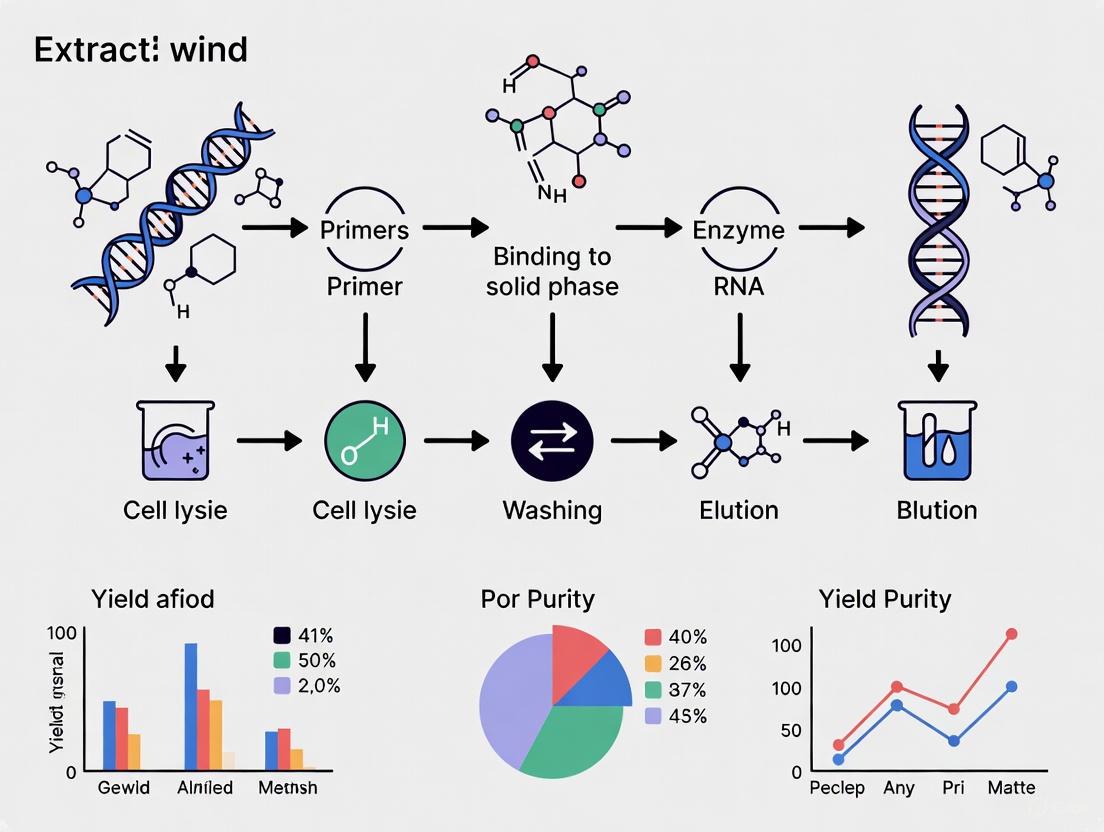

The Core Four-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the universal four-step nucleic acid extraction workflow, from sample input to final elution, including the key actions and objectives at each stage.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My nucleic acid yield is consistently low. What are the primary factors to investigate?

Low yield can stem from multiple points in the workflow. Systematically check the following:

- Incomplete Lysis: Insufficient lysis is a major cause [8]. Optimize by increasing incubation time with lysis buffer, using a more aggressive lysing matrix (e.g., bead beating for tough tissues), or adding enzymatic digestion with Proteinase K [9] [10].

- Inefficient Binding: Ensure the binding buffer has the correct pH; a lower pH (e.g., ~4.1) can significantly improve DNA binding to silica by reducing electrostatic repulsion [6]. Verify ethanol concentration is correct and that stocks are fresh, as old ethanol can absorb water and skew the working concentration [8]. For high-input samples, increase the volume of the binding matrix (e.g., silica beads) [6].

- Inefficient Elution: Elution efficiency is affected by pH, temperature, and duration [6]. Use a slightly basic elution buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5-9.0) instead of water, as DNA hydrates and dissolves more effectively in buffer. Let the buffer stand on the membrane for a few minutes before centrifugation [8].

Q2: My extracts have low purity (poor A260/A280 or A260/A230 ratios). How can I remove contaminants effectively?

Low purity indicates contamination with protein, salts, or other reagents.

- Protein Contamination (Low A260/A280): This suggests inadequate washing or overloading of the solid phase [8]. Ensure you are not exceeding the binding capacity of your column or beads. Perform the recommended wash steps thoroughly.

- Salt Contamination (Low A260/A230): This is often due to residual chaotropic salts or wash buffers [11] [8]. Ensure wash buffers are prepared with high-quality ethanol. If the problem persists, add an extra wash step with the provided ethanol-based wash buffer. After the final wash, a "dry spin" of the empty column is crucial to remove all residual ethanol [8].

- Specific Sample Inhibitors: For challenging samples like plants (polysaccharides) or blood (heme), use specialized kits that include additives like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to bind polyphenols or optimized wash buffers to remove specific inhibitors [7] [10].

Q3: I am working with a difficult sample type (e.g., plant, FFPE, blood). What special considerations are needed?

- Plant Tissues: These contain rigid cell walls and secondary metabolites. Use the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method or a specialized kit with PVP. Grind tissue in liquid nitrogen for efficient lysis [7] [10].

- Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissues: These require dewaxing and deparaffinization, often with xylene, followed by extended digestion with Proteinase K to reverse cross-links. Automated, non-xylene methods using heating and digestion are also available [10].

- Blood Samples: Use an anticoagulant like EDTA; avoid heparin as it inhibits PCR [9]. For fresh blood, a DNA stabilizer can prevent degradation. Remove protein precipitates by centrifugation before binding to prevent column clogging [9].

Quantitative Data for Method Selection

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from different DNA extraction methods as reported in recent studies, aiding in evidence-based protocol selection.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Reported Yield Range | Processing Time | Key Advantages | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform [12] | 50-100 ng/µL (from ticks) | Long (>1 hour) | High yield, high purity | Toxic reagents, labor-intensive, safety risks |

| Silica Column [12] [6] | 40-80 ng/µL (from ticks) | Moderate (~25 min) [6] | Good balance of yield and purity, convenient | Can be less efficient with high microbial loads [12] |

| Magnetic Beads [6] [12] | 20-96% of input DNA [6] | Rapid (6-7 min) [6] | Fast, automatable, high throughput | Potential bead carryover, equipment cost [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Detailed Methodology: Optimizing Binding Efficiency with Magnetic Silica Beads

This protocol is adapted from the SHIFT-SP method, which focuses on maximizing speed and yield [6].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Lysis/Binding Buffer (LBB): Contains guanidinium hydrochloride (a chaotropic salt) and Triton X-100, pH adjusted to 4.1.

- Magnetic Silica Beads

- Wash Buffer: Typically an ethanol-based saline solution.

- Elution Buffer (EB): 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5-9.0.

- Sample: Purified genomic DNA (e.g., from Mycobacterium smegmatis) spiked into LBB for optimization experiments.

2. Equipment:

- Thermonixer or heating block.

- Magnetic separation rack.

- Micro-pipettes.

- qPCR machine for quantification.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Binding.

- Mix the sample (containing 100-1000 ng DNA) with LBB and 10-50 µL of magnetic silica beads in a tube.

- For "tip-based" mixing, repeatedly aspirate and dispense the binding mix for 1-2 minutes. Alternatively, orbital shaking can be used but requires longer incubation (5-15 min) for similar efficiency [6].

- Incubate at 62°C during mixing.

- Step 2: Magnetic Separation and Washing.

- Place the tube on a magnetic rack until the solution clears.

- Carefully aspirate and discard the supernatant.

- Add wash buffer to the bead pellet, resuspend thoroughly and incubate for 30 seconds. Repeat this wash step twice.

- Step 3: Elution.

- After removing the final wash, add the pre-warmed Elution Buffer.

- Resuspend the beads and incubate at 70°C for 1-5 minutes.

- Place the tube back on the magnetic rack and transfer the eluate containing the purified DNA to a new tube.

4. Quantification and Analysis:

- Quantify the extracted DNA using a spectrophotometer or fluorometer.

- To precisely calculate binding and elution efficiency, use a qPCR-based approach [6]:

- Measure the amount of input DNA in the starting sample.

- Measure the amount of DNA left in the supernatant after binding.

- Measure the amount of DNA in the final eluate.

- Binding Efficiency (%) = (Input DNA - Supernatant DNA) / Input DNA × 100

- Elution Efficiency (%) = Eluted DNA / (Input DNA - Supernatant DNA) × 100

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Nucleic Acid Extraction and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Core Function | Optimization Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCl) [6] [8] | Denature proteins, inactivate nucleases, enable NA binding to silica. | Critical for both lysis and binding steps. |

| Silica Matrix (Membranes/Magnetic Beads) [6] [5] | Solid phase that selectively binds NA in high-salt conditions. | Bead size and surface chemistry impact yield; "tip-based" mixing improves binding kinetics [6]. |

| Proteinase K [5] [10] | Broad-spectrum protease that digests proteins and aids cell lysis. | Most effective in denaturing conditions; essential for tissues and FFPE samples. |

| Ethanol / Isopropanol [5] [8] | Promotes NA binding to silica; used in wash buffers to remove salts. | Use fresh, high-quality stocks; incorrect concentrations impair binding or washing. |

| Elution Buffer (TE Buffer, pH 8-9) [5] [8] | Hydrates and releases NA from the silica matrix in low-salt conditions. | Pre-warming and longer incubation (5 min) increase elution yield, especially for high MW DNA. |

| Inhibitor Removal Additives (e.g., PVP) [7] [10] | Binds to specific contaminants like plant polyphenols. | Add directly to the lysis buffer for samples rich in secondary metabolites. |

Key Workflow Considerations and Pathway

The following diagram outlines the critical decision points and parameters for optimizing each step of the nucleic acid extraction workflow.

The optimization of nucleic acid extraction is a foundational pillar in molecular biology, directly influencing the success of downstream applications in research and drug development. The pursuit of high yield and purity hinges on a detailed understanding of the key chemical agents that facilitate cell lysis, protein denaturation, and nuclease inhibition. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the core reagents—chaotropic salts, EDTA, SDS, and enzymes—framed within the context of troubleshooting and experimental optimization. By elucidating their specific mechanisms and interactions, we aim to empower researchers to systematically refine their protocols and overcome common challenges in nucleic acid purification.

Fundamental Roles and Mechanisms of Action

The following table summarizes the primary functions of these essential chemical agents.

Table 1: Key Chemical Agents in Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Chemical Agent | Primary Function | Mechanism of Action | Typical Concentration/Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCL, Guanidine Thiocyanate) | Protein denaturation & nucleic acid binding [8]. | Disrupt hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, denaturing proteins and nucleases; create conditions for nucleic acids to bind to silica membranes [8]. | Component of lysis and binding buffers; often used with ethanol [8]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Inhibition of nucleases [13]. | Chelates (binds) metal ions like Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺, which are essential cofactors for DNase and RNase activity [13]. | 1-10 mM in extraction buffers [13]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Cell lysis and protein denaturation [14]. | Anionic detergent that solubilizes membrane lipids and proteins, aiding in cell lysis; also stimulates Proteinase K activity [14]. | ~0.1-1% (e.g., 10 µL of 10% SDS in a 200 µL lysate) [14]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Proteinase K) | Digestion of cellular proteins. | Broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades proteins and nucleases, removing contaminants from the nucleic acid preparation [14]. | Concentration varies (e.g., >400 units/mL); incubation at 55°C [14]. |

Synergistic Interactions in a Standard Workflow

The effectiveness of nucleic acid extraction relies on the coordinated action of these reagents. The diagram below illustrates their sequential roles and synergistic relationships in a typical silica spin-column-based protocol.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

This section addresses specific problems related to extraction chemicals, their root causes, and evidence-based solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Nucleic Acid Extraction Problems

| Problem | Potential Chemical-Related Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Incomplete lysis due to inefficient SDS action or insufficient Proteinase K [15]. | Optimize lysis protocol; ensure correct SDS concentration; verify Proteinase K activity and incubation time/temperature [15]. |

| Inefficient binding to silica matrix [16]. | Ensure binding buffer (containing chaotropic salts) is fresh and mixed with the correct volume/quality of ethanol [8]. | |

| DNA/RNA Degradation | Ineffective nuclease inhibition due to insufficient EDTA or improper sample handling [15]. | Always include EDTA in lysis buffers; keep samples on ice; use nuclease-free consumables [13] [16]. |

| Protein Contamination | Incomplete protein digestion or removal [15]. | Extend Proteinase K digestion time (e.g., by 30 min to 3 hours) after tissue dissolution; ensure SDS is present to stimulate protease activity [15]. |

| Salt Contamination | Carryover of chaotropic salts from binding or wash buffers [15]. | Ensure wash buffers contain the correct ethanol concentration; perform a final "dry spin" with an empty column to evaporate residual ethanol [8] [15]. |

| Inhibition of Downstream Applications | Residual EDTA chelating Mg²⁺ ions essential for PCR [13]. | Use the correct concentration of EDTA (do not over-concentrate); consider a final purification step if excessive EDTA is suspected [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is EDTA so critical in nucleic acid extraction buffers? EDTA plays multiple protective roles. Its primary function is to chelate metal ions like Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺, which are essential cofactors for DNase and RNase activity. By removing these ions, EDTA significantly reduces nuclease activity, protecting the extracted nucleic acids from degradation [13]. Additionally, it aids in cell lysis by helping to remove metal ions bound to DNA within the cell, improves DNA solubility, and prevents metal-ion-induced precipitation [13].

Q2: My DNA appears intact on a gel, but my PCR fails. Could my extraction chemicals be the cause? Yes. Two common culprits are:

- Residual Chaotropic Salts: Inefficient washing can leave behind chaotropic salts that inhibit the polymerases used in PCR [16] [8]. Ensure wash steps are performed thoroughly.

- Residual EDTA: If the concentration is too high, EDTA can chelate the Mg²⁺ ions in the PCR reaction mix, which are an essential cofactor for Taq polymerase [13]. Using the recommended EDTA concentration in lysis buffers and ensuring proper washing can mitigate this.

Q3: How do chaotropic salts work in silica-based kits? Chaotropic salts have a dual function. First, they denature proteins, including nucleases, by disrupting hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, thereby stabilizing nucleic acids [8]. Second, they create a high-salt environment that dehydrates nucleic acid molecules and facilitates their selective binding to the silica membrane in spin columns, while proteins and other impurities are washed away [8].

Q4: What is the specific role of SDS when used with Proteinase K? SDS is an anionic detergent that acts synergistically with Proteinase K. It solubilizes cellular membranes and denatures proteins, making them more accessible for digestion by Proteinase K. Furthermore, SDS itself has been shown to stimulate the activity of Proteinase K, leading to more efficient and rapid digestion of cellular proteins [14].

Experimental Data and Protocol Optimization

Quantitative Effects of EDTA and Temperature on DNA Yield

A forensic study on DNA extraction from teeth provides quantitative insights into optimizing EDTA-containing buffers. The research demonstrated that incubating tooth powder with 0.5 M EDTA buffer at different temperatures significantly impacted DNA yield, with optimal results at 56°C [17]. This underscores the importance of temperature optimization during the demineralization and lysis steps when dealing with difficult samples.

Table 3: Effect of EDTA Buffer and Temperature on DNA Yield from Teeth

| Incubation Temperature | Relative DNA Yield | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 4°C | Low | Slow demineralization, insufficient for high yield. |

| 18°C | Low | Demineralization remains suboptimal. |

| 37°C | Moderate | Improved yield but not maximal. |

| 56°C | High | Optimal temperature for efficient demineralization and DNA release. [17] |

| 56°C (with distilled water) | Very Low | Highlights the essential role of EDTA. |

Detailed Protocol: Mammalian Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction

The following workflow, adapted from a commercial kit protocol, illustrates the precise points where key chemical agents are utilized to maximize yield and purity [14].

Key Optimizations from the Protocol:

- Tissue Preparation: Mincing tissue into the smallest possible pieces (<25 mg) is critical for efficient lysis and prevents nuclease degradation [15].

- Digestion Conditions: Lysis Buffer containing EDTA is used with Proteinase K and SDS, followed by incubation at 55°C for ~3 hours (or overnight) to ensure complete digestion [14].

- RNA Removal: An optional RNase A digestion step is included to minimize RNA contamination, which is particularly important for DNA-rich tissues like liver and spleen [14] [15].

- Binding Conditions: The addition of Binding Buffer (containing chaotropic salts) and a precise volume of ethanol (200 µL of 96-100%) is essential for maximum binding of DNA to the silica membrane [8] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table catalogs the fundamental reagents, their functions, and key considerations for use in optimizing nucleic acid extraction protocols.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations for Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (Guanidine HCl/Thiocyanate) | Denatures proteins; enables nucleic acid binding to silica. | Ensure fresh, high-quality ethanol is used in the binding step. Old ethanol stocks can absorb water, reducing effective concentration and binding efficiency [8]. |

| EDTA | Chelates metal ions; inhibits nucleases. | Use at 1-10 mM concentration. Too high a concentration can inhibit downstream PCR by chelating Mg²⁺ [13]. |

| SDS | Ionic detergent for cell lysis and protein denaturation. | Can precipitate in the presence of guanidine isothiocyanate; a subsequent heating step (70°C for 10 min) is often used to re-solubilize it [14]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum protease for digesting proteins. | Works effectively in the presence of SDS and EDTA. Incubation temperature (55°C) and time (1-3 hours or more) must be optimized for the sample type [14] [15]. |

| Ethanol | Promotes nucleic acid binding to silica in the presence of chaotropic salts; used in wash buffers. | Must be of high purity (96-100%). Used in wash buffers to remove salts without eluting DNA [8]. |

| RNase A | Degrades RNA to prevent contamination of DNA preparations. | An optional but recommended step for tissues with high RNA content. Ensures accurate DNA quantification and unimpeded downstream applications [14]. |

| Elution Buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, TE buffer) | Hydrates and releases nucleic acids from the silica membrane. | Slightly basic pH (8-9) is ideal for DNA elution and stability. Allowing the buffer to sit on the membrane for a few minutes before centrifugation can increase yield [8]. |

Nucleic acid extraction is a foundational step in molecular biology, critical for applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to next-generation sequencing. However, the path to obtaining high-yield, high-purity DNA or RNA is often obstructed by the unique biochemical and physical properties of different sample types. Blood contains potent PCR inhibitors, stool is a complex mixture of host and microbial DNA with abundant inhibitors, tissues present structural and enzymatic barriers, and microbial cells have robust walls resistant to lysis. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate these sample-specific challenges, all within the broader context of optimizing nucleic acid extraction for superior yield and purity.

Sample-Specific Challenges and Solutions

Blood Samples

Key Challenges: Blood contains potent PCR inhibitors like heme and immunoglobulin, and samples can have low pathogen concentration in a high-background of human DNA [18] [10]. The venepuncture process also introduces contamination risk from skin flora [18].

Optimized Protocol (Magnetic Silica Bead-Based):

- Lysis: Use a lysis binding buffer (LBB) at pH 4.1 rather than pH 8.6. Research shows pH 4.1 achieves 98.2% DNA binding within 10 minutes, compared to 84.3% at 15 minutes for higher pH, by reducing electrostatic repulsion between silica and negatively charged DNA [6].

- Binding: Employ "tip-based" mixing (aspirating and dispensing repeatedly) instead of orbital shaking. For 100ng input DNA, tip-based mixing achieves ~85% binding in 1 minute versus ~61% with orbital shaking [6].

- Elution: Optimize elution buffer pH and temperature. Higher temperatures (62°C) can significantly improve elution efficiency [6].

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: How can I improve DNA yield from low-concentration blood samples?

- A: Implement a method that maximizes binding efficiency. The SHIFT-SP method, which uses tip-based mixing and optimized pH, extracts nearly all nucleic acid in the sample and can process microbes from enriched whole blood for downstream whole genome amplification and sequencing [6].

- Q: My blood DNA extracts show inhibition in downstream PCR. What steps can I take?

- A: Ensure thorough washing steps to remove heme and other inhibitors. Magnetic bead-based methods with optimized chemistries can effectively target genomic DNA while removing sample-specific inhibitors [10].

Stool Samples

Key Challenges: Stool contains complex microbial communities and high levels of PCR inhibitors including bilirubin, complex polysaccharides, and bile salts [10]. The ratio of host to microbial DNA can also be problematic for certain analyses.

Optimized Protocol:

- Homogenization: Use specialized bead tubes in a homogenizer like the Bead Ruptor Elite for mechanical disruption. Optimize speed, cycle duration, and bead type to balance effective disruption with DNA integrity [19].

- Inhibitor Removal: Use specialized kits that incorporate compounds like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to adsorb polyphenols [10].

- Stabilization: For stored samples, use stabilization media to prevent bacterial growth and degradation. Note that stabilized samples may yield less DNA, so input volume may need adjustment [10].

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: How can I reduce co-extraction of inhibitors from stool samples?

- A: Incorporate multiple wash steps with optimized buffers. Guanidinium thiocyanate-based extractions may result in better inhibitor removal from different sample types than other methods [6].

- Q: My stool DNA yields are low after stabilization in transport media. What should I do?

- A: Consider using two swabs in a single isolation or increasing the input volume. For stool swabs in media, mechanical homogenization may not be needed for microbial DNA identification [10].

Tissue Samples

Key Challenges: Tissues are often fibrous with rigid cell walls that complicate lysis [10]. They also contain abundant nucleases that can degrade DNA, and some tissues are rich in inhibitors like lipids and pigments.

Optimized Protocol:

- Disruption: For fresh/frozen tissue, use freeze-grinding in liquid nitrogen to powder the tissue without repeated freeze-thaw cycles [7].

- Lysis: Use a buffer containing 10mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 100mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, and 200μg/mL protease K, incubated at 37-55°C until tissue is dissolved [7].

- DNA Protection: Include EDTA in the lysis buffer to chelate metals and inhibit nuclease activity [7] [19].

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: How can I prevent DNA degradation during tissue extraction?

- A: Work quickly, use nuclease inhibitors, and maintain appropriate temperatures. Excessive heating during homogenization can accelerate DNA oxidation and hydrolysis [19].

- Q: What is the best approach for FFPE tissue samples?

Microbial Samples

Key Challenges: Microbial cell walls are robust and resist standard lysis methods. Gram-positive bacteria with thick peptidoglycan layers are particularly challenging. Environmental samples also often contain difficult-to-lyse spores.

Optimized Protocol:

- Lysis: Use bead beating with specialized beads (ceramic, stainless steel) optimized for microbial disruption [19].

- Inhibitor Removal: Guanidinium thiocyanate-based extractions are excellent at denaturing proteins such as DNases and inactivating viruses in samples during NA extraction [6].

- Binding Conditions: For magnetic bead-based methods, ensure proper pH and binding time. Studies show that extending binding time to 2 minutes with increased bead quantity (30-50μL) can achieve >90% binding efficiency for higher DNA inputs [6].

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: How can I improve lysis of tough microbial cells like Gram-positive bacteria?

- A: Implement a combination approach of mechanical and chemical lysis. Bead beating with the Bead Ruptor Elite using optimized bead tubes can efficiently disrupt tough-to-lyse bacterial samples, yielding lysate suitable for downstream analysis [19].

- Q: My microbial DNA extraction from low-biomass samples has high background contamination. How can I address this?

- A: Include appropriate negative controls throughout the process. Studies have shown that bacteria from skin flora and laboratory reagents can contaminate samples, especially in low-microbial biomass environments [18].

Comparative Performance Data

Extraction Method Efficiency

| Extraction Method | Processing Time | Relative DNA Yield | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHIFT-SP (Bead-Based) [6] | 6-7 minutes | ~100% | Highest speed, automation compatible, efficient for both DNA and RNA |

| Commercial Bead-Based [6] | ~40 minutes | Similar to SHIFT-SP | Established protocol |

| Commercial Column-Based [6] | ~25 minutes | ~50% of SHIFT-SP | Widely accessible |

| Phenol-Chloroform [7] | 60+ minutes | High | High purity, cost-effective for small batches |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles [20] | Not specified | Cost-effective | Cost-effective, developing technology |

Sample-Specific Troubleshooting Guide

| Sample Type | Common Issue | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Blood [18] [10] | PCR inhibition from heme | Increase wash steps; use inhibitor removal chemistry |

| Stool [10] | Low yield from stabilized samples | Increase input material; extend lysis time |

| Tissue [7] [19] | DNA degradation during processing | Optimize homogenization settings; add nuclease inhibitors |

| Microbes [6] [19] | Incomplete cell lysis | Combine mechanical and chemical lysis methods |

| FFPE Tissue [7] [10] | DNA cross-linking and fragmentation | Incorporate high-temperature protease digestion |

| Plant [7] [10] | Polysaccharide/polyphenol contamination | Add PVP to extraction buffer |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Silica Beads [6] | Nucleic acid binding and separation | SHIFT-SP protocol; automated extraction systems |

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate [6] | Chaotropic salt; denatures proteins, inactivates nucleases | Lysis buffer for blood, microbial samples |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [10] | Adsorbs polyphenols | Plant extracts; stool samples |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) [7] [19] | Chelating agent; inhibits nucleases | Tissue lysis buffers; bone demineralization |

| CTAB Buffer [7] | Selective precipitation of nucleic acids | Plant DNA extraction (gold standard) |

| Protease K [7] | Digests proteins; inactivates nucleases | Tissue lysis; FFPE sample processing |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles [20] | Alternative binding matrix for DNA | Cost-effective DNA isolation |

Optimizing nucleic acid extraction across diverse sample types requires both understanding fundamental biochemical challenges and implementing targeted methodological solutions. The protocols and troubleshooting guides presented here provide evidence-based approaches for overcoming the specific barriers presented by blood, stool, tissues, and microbial samples. As extraction methodologies continue to advance—with innovations like the SHIFT-SP method dramatically reducing processing times while maintaining high yields—researchers are better equipped than ever to obtain the high-quality nucleic acids essential for reliable downstream applications in drug development and clinical diagnostics.

A Practical Guide to Modern Nucleic Acid Extraction Techniques

Within the context of optimizing nucleic acid extraction yield and purity, the phenol-chloroform method, often termed organic extraction, maintains a significant legacy position. As molecular biology evolves towards automation and high-throughput systems, understanding this foundational technique remains crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It is historically the most common, tried-and-true method for isolating RNA and removing cellular proteins [21]. The core principle relies on the partitioning of biomolecules between an aqueous phase and an organic phase based on their chemical properties and solubility [22]. Proteins and lipids tend to partition into the organic phase, while nucleic acids, being hydrophilic, remain in the aqueous phase [22]. This process is pH-dependent; for DNA extraction, neutral or slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7-8) are used to ensure DNA remains in the aqueous phase, while acidic conditions favor RNA recovery [21] [22]. Despite the advent of newer methods, organic extraction is still valued for its ability to yield high-purity DNA from complex samples and its cost-effectiveness for large sample volumes [22]. This article details the advantages, limitations, and specific scenarios where this method continues to be the preferred choice for nucleic acid purification.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

The Scientific Workflow of Organic Extraction

The organic extraction protocol is a multi-step process designed to separate nucleic acids from other cellular components. The following diagram illustrates the key stages from sample input to final elution, highlighting critical decision points that influence yield and purity.

Diagram 1: The Organic Extraction Workflow. This process involves sample homogenization in a phenol-containing solution, phase separation via centrifugation, careful recovery of the aqueous phase containing nucleic acids, and final precipitation and washing steps to obtain pure DNA or RNA [21] [23].

Quantitative Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

The selection of a nucleic acid extraction method involves trade-offs between yield, purity, scalability, and safety. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary techniques used in laboratories today, providing a direct comparison for informed decision-making.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Common Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

| Feature | Organic Extraction | Spin Column Method | Magnetic Bead Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Liquid-phase partitioning based on solubility in organic solvents [21] [22] | Solid-phase adsorption to a silica membrane [21] | Solid-phase adsorption to silica-coated magnetic beads [21] [6] |

| Typical Yield | High (e.g., 50-100 ng/µL from ticks) [12] | Moderate (e.g., 40-80 ng/µL from ticks) [12] | Variable, can be very high (e.g., 20-70 ng/µL from ticks; ~96% efficiency in SHIFT-SP method) [12] [6] |

| Purity | High, effective protein separation [22] [7] | High [24] [7] | High [24] |

| Throughput | Low, not amenable to automation [21] | High, amenable to 96-well plates [21] | Very high, easily automated [21] [24] |

| Cost | Low (uses common lab reagents) [24] [22] | Moderate (commercial kits) [21] | Higher (specialized beads and equipment) [21] [25] |

| Key Advantage | Gold standard for purity; cost-effective for large volumes [21] [22] | Simple, convenient, ready-to-use kits [21] | Automation, high-throughput, rapid processing [21] [6] [24] |

| Key Disadvantage | Use of toxic chemicals; labor-intensive [21] [22] [23] | Membrane clogging with large/impure samples [21] | Higher cost; bead carryover risk [21] [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Organic Extraction

Successful execution of the organic extraction protocol requires a set of specific reagents, each serving a critical function in the separation and purification process.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Organic Extraction

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Phenol | Denatures proteins by disrupting hydrogen bonds, allowing nucleic acids to remain in the aqueous phase [22]. | pH is critical: acidic for RNA, neutral/alkaline for DNA extraction [21] [22]. |

| Chloroform | Enhances phase separation and promotes partitioning of proteins and lipids into the organic phase [22]. | Often mixed with isoamyl alcohol (24:1) to reduce foaming [22] [23]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that solubilizes cell and nuclear membranes, facilitating the release of intracellular contents [22] [23]. | Effective in combination with Proteinase K for comprehensive lysis [23]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease that digests and inactivates nucleases, protecting nucleic acids from degradation [7] [23]. | Requires incubation at 37-55°C for several hours for complete digestion [7]. |

| Chaotropic Salt (e.g., Guanidine) | Denatures proteins and inactivates nucleases (e.g., DNases, RNases); used in some lysis buffers [6]. | Guanidinium thiocyanate-based extractions can improve inhibitor removal [6]. |

| Ethanol / Isopropanol | Precipitates nucleic acids from the aqueous solution after extraction, aiding in their recovery and concentration [22] [23]. | Used ice-cold; isopropanol is preferred for precipitating lower concentrations of DNA [23]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Even with a well-established protocol, researchers can encounter issues that compromise yield and purity. This section addresses frequent challenges and provides evidence-based solutions.

FAQ 1: An emulsion forms during the phase separation step, preventing a clean separation. How can I resolve this?

Emulsion formation is a common problem, often occurring when samples contain high amounts of surfactant-like compounds such as phospholipids, free fatty acids, proteins, or triglycerides [26].

- Prevention is key: Gently swirl or invert the tube instead of shaking it vigorously. This reduces agitation while maintaining the surface area for extraction [26].

- Salting Out: Add brine or saturated salt solution (e.g., NaCl) to increase the ionic strength of the aqueous layer. This can force the surfactant-like molecules to separate into one phase or the other, breaking the emulsion [26].

- Centrifugation and Filtration: Centrifuging the sample can help isolate the emulsion material. Alternatively, the emulsion can be filtered through a glass wool plug or a highly silanized phase separation filter paper designed to allow one phase to pass through [26].

- Alternative Solvents: Adding a small amount of a different organic solvent can adjust the solvent properties and break the emulsion [26].

- Alternative Method: For samples consistently prone to emulsions, consider Supported Liquid Extraction (SLE), which uses a solid support (e.g., diatomaceous earth) to create an interface for extraction, thereby avoiding emulsion formation altogether [26].

FAQ 2: My final DNA yield is consistently low. What are the potential causes and optimizations?

Low yield can stem from incomplete precipitation, inefficient phase separation, or sample handling errors.

- Ensure Complete Precipitation: Use ice-cold ethanol or isopropanol and ensure sufficient incubation time at -20°C (e.g., overnight) to maximize DNA precipitation [23] [27]. The addition of carriers like glycogen can also improve the recovery of微量 nucleic acids [25].

- Optimize Phase Separation: During the aqueous phase transfer, take extreme care not to disturb the protein interphase. Even a small amount of contamination can lead to protein carry-over that interferes with downstream precipitation [21] [23]. Using phase-lock gel tubes can make this process easier and more reliable [25].

- Verify pH Conditions: For DNA extraction, the phenol must be equilibrated to a neutral or slightly basic pH (7-8). An incorrect pH can cause DNA to partition into the organic phase or interphase, drastically reducing yield [21] [22].

- Improve Lysis Efficiency: For difficult-to-lyse samples (e.g., ticks, plant tissues, Gram-positive bacteria), incorporate a mechanical disruption step such as bead-beating with glass beads. A study on DNA extraction from stool parasites found that adding a bead-beating step to the phenol-chloroform protocol significantly improved DNA yield and subsequent PCR detection rates [27].

FAQ 3: My nucleic acid sample is contaminated with protein. How can I improve purity?

Protein contamination is typically indicated by a low A260/A280 ratio in spectrophotometric analysis.

- Repeat Extraction: The most direct solution is to perform a second round of extraction on the recovered aqueous phase. Add an equal volume of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1), mix, centrifuge, and carefully recover the aqueous phase. This step removes residual phenol and any remaining protein [23].

- Ensure Proper Initial Ratios: Confirm that the volumes of the sample lysate and the phenol-chloroform mixture are equal. An incorrect ratio can lead to incomplete protein removal [23].

Legacy Uses and Modern Research Applications

Despite its manual nature, organic extraction remains the preferred or required method in several advanced research contexts due to its unparalleled ability to handle complex samples and deliver high yields.

- Virome Studies: The phenol-chloroform DNA extraction protocol is currently the gold standard for studying viral metagenomes (viromes) from diverse environments like human gut, animal microbiomes, and soil [25]. Its effectiveness in extracting viral nucleic acids from these complex samples makes it a benchmark against which newer kit-based methods are validated [25].

- Challenging Sample Types: For samples that are rich in PCR inhibitors or have resilient structures (e.g., tick exoskeletons, fungal spores, plant tissues rich in polysaccharides and polyphenols), organic extraction often provides superior yields. A systematic review on DNA extraction from ticks noted that phenol-chloroform extraction achieved high DNA yields (50-100 ng/µL), albeit with safety risks and longer processing times [12].

- High-Purity Requirements: In applications where the highest possible purity is critical for downstream processes, such as long-read sequencing, cloning, or sensitive enzymatic assays, the rigorous purification offered by organic extraction is often favored over other methods [22] [7]. It is also widely used in proteomic studies for protein extraction and purification, where organic solvents like phenol-acetone are used to denature and precipitate proteins away from contaminants [22].

The following decision tree can help researchers determine when organic extraction is the most appropriate choice for their experimental goals.

Diagram 2: Nucleic Acid Extraction Method Selection Guide. This flowchart assists in selecting the optimal extraction method based on sample type, research priorities, throughput, safety, and budget [21] [12] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions for Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

| Problem | Common Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Recovery Rate [28] | Target compound is insufficiently retained on the adsorbent. [28] | Adjust the sample pH to neutralize the analyte's charge for better retention on non-polar sorbents; for ion-exchange, ensure pH favors analyte charging. [29] |

| Target compound is not completely eluted. [28] | Use a stronger elution solvent; adjust pH to ionize the compound; add an organic modifier; use multiple elution aliquots with a soak step. [30] [29] | |

| Poor Reproducibility [28] | Column bed dries out before sample loading. [28] | Do not let the cartridge run dry after conditioning; re-condition if unsure. [29] |

| Sample flow rate is too fast. [28] | Process samples at a slower flow rate, typically around 1 mL/min, and as low as 100 µL/min for ion-exchange mechanisms. [30] | |

| Undesirable Purification Effect [28] | Incorrect purification mode or lack of selectivity. [28] | Use a selective sorbent (e.g., ion-exchange > normal phase > reversed-phase); optimize wash and elution solvent strengths. [28] [30] |

| Slow Flow Rate [28] | Sample contains particulate impurities. [28] | Centrifuge or filter the sample solution before loading. [28] |

| Sample viscosity is too high. [28] | Dilute the sample with a compatible solvent before loading. [28] | |

| Analyte Breakthrough | Sorbent is not properly conditioned and equilibrated. [30] | Condition with methanol followed by water or a buffer that matches the sample's pH and ionic strength. [30] [29] |

| Flow rate during loading is too high. [31] | Load the sample at a slow, controlled flow rate without applying pressure initially. [29] |

Common Issues and Solutions for Nucleic Acid Spin Kits

| Problem | Common Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Insufficient cell or tissue lysis. [32] [33] | Increase digestion or homogenization time; optimize lysis protocol for your sample type. [32] [33] |

| Column is overloaded with sample. [32] [34] | Reduce the amount of starting material to within the kit's specifications. [32] [34] | |

| Inefficient binding of nucleic acids to the silica membrane. [33] | Ensure the binding buffer is correct; optimize incubation time and mixing. [33] | |

| Nucleic Acid Degradation | Action of nucleases in the sample. [32] [33] [34] | Use nuclease-free reagents; work quickly on ice; use RNase inhibitors for RNA; flash-freeze samples after collection. [32] [33] [34] |

| Poor sample storage. [34] | Flash-freeze tissue samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C; use RNA/DNA stabilization reagents. [32] [34] | |

| Salt Contamination (Low A260/230) | Carryover of guanidine salts from binding buffer. [32] | Ensure wash buffers are used; do not let the column contact flow-through; centrifuge again if needed; blot collection tube rim if reused. [32] |

| Protein Contamination (Low A260/280) | Incomplete protein digestion or removal. [32] [34] | Ensure Proteinase K digestion is complete; centrifuge lysate to pellet debris before loading onto the column. [32] [34] |

| DNA Contamination in RNA Preps | gDNA carryover. [32] | Perform an on-column or in-solution DNase I digestion step. [32] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do I choose the right sorbent for my SPE application? The choice of sorbent is critical and depends on your analyte and sample matrix. The general selectivity rule is Ion-Exchange > Normal Phase > Reversed Phase [28]. For non-polar analytes, use reversed-phase sorbents (e.g., C18). For polar compounds, normal-phase sorbents are suitable. For ionizable compounds, ion-exchange sorbents are highly selective [30] [31]. Knowing your analyte's logP/logD and pKa values is invaluable for this decision [30].

2. Why is conditioning and equilibration of the SPE column necessary? Conditioning (typically with methanol or acetonitrile) prepares or "wets" the sorbent surface, ensuring maximum capacity and interaction with your analyte [29]. The subsequent equilibration step (with water or a buffer similar to your sample) ensures the sorbent environment matches the sample solvent. This prevents the sample from being repelled by the sorbent and minimizes the risk of analyte breakthrough [30] [29].

3. My nucleic acid yield is low but the lysis looked complete. What could be wrong? A common cause is inefficient binding of the nucleic acids to the silica membrane. Confirm that your binding buffer is prepared correctly and has the right pH. Also, ensure adequate incubation and mixing time after adding the binding buffer to the lysate to allow the nucleic acids to bind efficiently to the silica matrix [33].

4. My extracted nucleic acids are degraded. How can I prevent this? Degradation is often due to nucleases. Always use nuclease-free tips and tubes. Work quickly and on ice whenever possible. For RNA, use specific RNase inhibitors. When collecting samples, especially tissues, flash-freeze them immediately in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C to preserve integrity [32] [33] [34].

5. How can I improve the purity of my nucleic acids for sensitive downstream applications? Ensure you are using the correct volumes of wash buffers and that they contain the appropriate ethanol concentration. Before elution, make sure wash buffers are completely removed. Consider an additional wash step or extending the centrifugation time for the final wash. For DNA contamination in RNA, incorporate a DNase I digestion step [32].

Experimental Protocols & Optimization

Method for Optimizing SPE Wash and Elution Solvents

1. Objective: To determine the optimal solvent strength for washing and eluting your target analyte from an SPE cartridge, maximizing recovery while minimizing co-elution of impurities [28] [30].

2. Methodology:

- For Reversed-Phase Mode:

- Load your target compound in an aqueous solution onto the conditioned SPE cartridge.

- Elute the cartridge with a series of methanol-in-water solutions of increasing concentration (e.g., 5%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%).

- Collect each eluate fraction separately and analyze them to determine the methanol concentration at which your compound just begins to elute and when it is completely eluted [28].

- For Normal-Phase Mode:

- Load your target compound in a non-polar solvent like n-hexane.

- Elute with a series of n-hexane and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) with increasing MTBE concentration.

- Collect and analyze fractions as above [28].

3. Optimization:

- The wash solvent should have a strength just below the point where your analyte begins to elute. This will remove impurities without losing your target [30].

- The elution solvent should have a strength just above what is required to completely elute your analyte. This avoids using an excessively strong solvent that would elute more impurities [28] [30].

On-Column DNase I Digestion for RNA Purification

1. Objective: To remove genomic DNA contamination during RNA extraction using a spin kit [32].

2. Detailed Workflow:

- After loading the sample lysate onto the spin column and washing it with the appropriate wash buffer, prepare the DNase I reaction mix.

- Pipette the DNase I solution directly onto the center of the silica membrane.

- Incubate the column at room temperature for 15 minutes, as specified in the kit protocol.

- After incubation, perform a wash step with the kit's wash buffer to remove the DNase I enzyme and any digested DNA fragments.

- Proceed with the final wash steps and elution as normal [32].

Key Workflow Diagrams

SPE Method Development Logic

Nucleic Acid Spin Column Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| C18 Sorbent | A reversed-phase sorbent ideal for extracting non-polar to moderately polar organic compounds from aqueous matrices. A versatile and common choice. [35] [31] |

| Ion-Exchange Sorbents (SAX, SCX) | Selective sorbents for extracting ionizable analytes. SAX (Strong Anion Exchange) for acids; SCX (Strong Cation Exchange) for bases. Offers high selectivity. [28] [35] |

| Silica-based Sorbents | The foundation for many functionalized sorbents (C18, C8, etc.). The silica particle size and pore structure impact efficiency and flow. [35] |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease used in nucleic acid extraction to digest histones and other cellular proteins, degrading nucleases and helping to release nucleic acids. [32] [34] |

| RNase A & DNase I | Specific nucleases for removing unwanted nucleic acids. RNase A removes RNA from DNA preparations, while DNase I removes genomic DNA from RNA preparations. [32] [34] |

| Binding Buffer (Guanidine Salts) | A key component in spin kits. High concentrations of chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine thiocyanate) disrupt the hydration shell of nucleic acids, allowing them to bind efficiently to the silica membrane. [32] [34] |

| Wash Buffer (Ethanol) | Typically contains ethanol or another appropriate solvent. It removes salts, metabolites, and other contaminants from the silica membrane while leaving the nucleic acids bound. [32] |

Core Principles of Magnetic Bead-Based Separation

Magnetic bead-based systems utilize superparamagnetic particles to isolate and purify biomolecules like nucleic acids or proteins from complex samples. The core principle involves a magnetic core (often iron oxide) that becomes magnetized only in the presence of an external magnetic field, preventing self-aggregation and allowing redispersion when the field is removed [36]. This magnetic core is surrounded by a protective coating and a functionalized surface with reactive groups (e.g., carboxyl, amine, or streptavidin) that enable specific binding to target molecules [37] [36].

The workflow operates through a series of controlled buffer conditions. Under high-salt, chaotropic conditions (e.g., with guanidine isothiocyanate), nucleic acids bind specifically to the functionalized bead surface. When placed near a magnet, the beads are immobilized against the tube or plate wall, allowing impurities to be washed away. Finally, the purified nucleic acids are eluted in a low-salt buffer or water [37] [38]. This mechanism provides a solid-phase extraction method that eliminates the need for centrifugation, making it particularly suitable for automation and high-throughput applications [39] [38].

Standard Workflow for Nucleic Acid Extraction

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction, from sample preparation to final elution.

Detailed Protocol for High-Throughput Nucleic Acid Extraction

Sample Lysis and DNA Binding:

- Add 25 mL of pre-warmed (65°C) CTAB extraction buffer to 30 mL of sample. The buffer should contain chaotropic salts like 1 M guanidine isothiocyanate (GITC) to facilitate DNA binding [37].

- Mix the solution at 45 rpm for 3 hours using a digital rotator to ensure proper interaction between the DNA and magnetic beads [37].

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 20°C to separate phases. Carefully remove the upper oily phase (supernatant) [37].

DNA Precipitation and Purification:

- Add an acryl carrier solution (5 μL per 1 mL sample), followed by 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and an equal volume of isopropanol [37].

- Incubate overnight at -20°C to precipitate DNA. Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C, discard supernatant, and resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of specific solution [37].

- Add 0.2 mg of carboxyl-modified magnetic beads (300 nm diameter) to the aqueous DNA solution, followed by a specific volume of ethanol/isopropanol. Mix gently by inversion and incubate for 10 minutes to facilitate DNA binding [37].

Washing and Elution:

- Separate the beads using a Magnetic Separator Stand and wash twice with 1 mL of 70% ethanol (v/v) to remove impurities [37].

- Air-dry beads at room temperature for 3-5 minutes to evaporate residual ethanol [37].

- Elute DNA by adding 100 μL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA-2Na, pH 8.0), mixing thoroughly, and incubating at 60°C for 10 minutes. Separate beads until the TE buffer is clear and transfer eluted DNA to a clean storage tube [37].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Low Nucleic Acid Yield

- Cause: Suboptimal bead-to-sample ratio or insufficient mixing during binding [40].

- Solution: Ensure accurate pipetting and reagent proportions. Use a sample mixer (e.g., HulaMixer) during incubation steps to maintain consistent suspension and maximize binding surface contact [40].

- Cause: Incomplete elution due to inadequate buffer volume or contact time.

- Solution: Ensure beads are fully resuspended in elution buffer. Pre-warm elution buffer to 60°C and increase incubation time to 10 minutes to enhance DNA release [37].

Poor Nucleic Acid Purity

- Cause: Residual contaminants from incomplete washing [39].

- Solution: Incorporate additional wash steps with 70% ethanol. For challenging samples like tissues, introduce an extra chloroform extraction step during sample preparation to remove lipids and proteins effectively [39].

- Cause: Contaminated reagents or buffers.

- Solution: Prepare fresh ethanol wash buffers daily and filter-sterilize solutions to prevent nuclease or particulate contamination [39].

Inconsistent Results Between Samples

- Cause: Variable bead sedimentation during processing [40].

- Solution: Standardize mixing procedures across all samples. Use an orbital shaker or rotator that provides consistent, gentle agitation to maintain beads in uniform suspension [40].

- Cause: Improper storage or handling of magnetic beads.

- Solution: Store beads according to manufacturer specifications. Avoid repeated freezing and thawing, and vortex beads thoroughly before use to ensure homogeneous dispersion [41].

Beads Not Binding Target Molecules Effectively

- Cause: Degraded or low-quality magnetic beads [41].

- Solution: Check expiration dates and storage conditions. Verify bead integrity and binding capacity using a control sample with known nucleic acid concentration [41].

- Cause: Incorrect buffer pH or composition interfering with binding chemistry [41].

- Solution: Ensure coupling buffers are at correct pH (typically pH 6.0 for carboxyl-modified beads) and concentration. Avoid buffers containing primary amines (like Tris) when using amine-reactive coupling chemistries [37] [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and their functions in magnetic bead-based workflows.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| Carboxyl-Modified Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase support for nucleic acid binding under high-salt conditions; 300 nm size optimal for DNA recovery [37]. |

| Guanidine Isothiocyanate (GITC) Buffer | Chaotropic agent that denatures proteins and facilitates nucleic acid binding to magnetic beads [37]. |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) Buffer | Facilitates transfer of DNA from organic to aqueous phase, particularly useful for complex samples like plant tissues or oils [37]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that digests proteins and nucleases, eliminating contaminants and protecting nucleic acids from degradation [42]. |

| RNAse A | Removes contaminating RNA from DNA preparation, ensuring pure DNA extraction without RNA interference [42]. |

| Ethanol (70%) | Wash solution that removes salts and other impurities while maintaining nucleic acid binding to beads [37]. |

| TE Buffer (Tris-EDTA) | Elution solution that chelates magnesium to inhibit DNase activity and stabilizes nucleic acids for long-term storage [37]. |

| Sodium Acetate (3M) | Facilitates ethanol precipitation of nucleic acids, enhancing recovery during concentration steps [37]. |

Performance Optimization Data

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from optimized magnetic bead-based extraction protocols, demonstrating their efficiency for high-throughput applications.

| Application/Matrix | Recovery Efficiency | Purity (A260/A280) | Key Optimized Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refined Soybean Oil [37] | 76.37% | ~2.0 (PCR compatible) | 1 M GITC buffer, pH 6.0 with 300 nm carboxyl beads |

| Non-Human Primate Tissues [39] | Significantly increased with modified protocol | ~2.0 (improved with chloroform) | Additional chloroform and ethanol steps |

| PCR Product Purification [38] | Excellent, especially for small fragments | Suitable for sequencing/cloning | Automation-compatible 96-well plate format |

| High-Throughput Automated RNA [39] | Varies by kit; improved with protocol modification | ~2.0 across kits | Standardized protocol for interlaboratory comparisons |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the advantages of magnetic bead-based systems over spin columns for high-throughput labs?

Magnetic bead systems enable full automation on robotic liquid-handling platforms, support 96- or 384-well plate formats, and eliminate centrifugation steps. This significantly reduces hands-on time while providing excellent recovery rates, particularly for small fragments or low-concentration samples [38].

How can I improve nucleic acid yield from difficult sample types like refined oils or fatty tissues?

Implement a CTAB-based phase separation step before magnetic bead purification. This effectively transfers DNA from the oil phase to the aqueous phase. Additionally, use carboxyl-modified magnetic beads (300 nm) with optimized GITC buffer conditions (1 M, pH 6.0) to maximize recovery from challenging matrices [37].

Why is my nucleic acid purity insufficient for downstream applications like qPCR?

Incorporate additional purification steps such as chloroform extraction to remove co-precipitating contaminants. Ensure wash buffers are fresh and applied in sufficient volumes. For automated systems, verify that the washing steps are thoroughly replacing previous solutions without cross-contamination [39].

Can magnetic bead-based systems be fully automated?

Yes, magnetic bead systems are ideal for automation. Platforms like the KingFisher Flex can be integrated with pipetting robots (e.g., ASSIST PLUS) to create walk-away purification workflows. Specialized modules like MAG and HEATMAG provide magnetic separation with heating capabilities for streamlined processing [43] [39].

How critical is bead size selection for extraction efficiency?

Bead size significantly impacts performance. For DNA extraction from refined oils, 300 nm carboxyl-modified beads demonstrated optimal DNA adsorption compared to 100 nm or 500 nm beads. The larger surface-to-volume ratio of appropriately sized beads enhances biomolecular adsorption efficiency [37] [36].

What quality control measures should I implement for consistent results?

Regularly verify bead binding capacity using control samples. Monitor extraction efficiency with internal positive controls (IPC) like VetMAX Xeno IPC RNA. Track nucleic acid purity through absorbance ratios (A260/A280) and confirm integrity via electrophoretic analysis [39].

In the context of optimizing nucleic acid extraction for molecular diagnostics and research, rapid protocols like boiling and heat-shock methods offer significant advantages in speed and cost-effectiveness. These techniques leverage high temperatures to disrupt cell membranes and denature proteins, facilitating the release of nucleic acids without the need for complex purification systems. Framed within a broader thesis on extraction optimization, this technical support center addresses the practical challenges and methodological refinements necessary to implement these protocols successfully. While ideal for high-throughput screening and resource-limited settings, these methods require precise troubleshooting to ensure yield and purity compatible with downstream applications like PCR and sequencing [44] [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problems and Solutions for Boiling Protocols

Problem: Low Nucleic Acid Yield

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incomplete Cell Lysis: Ensure thorough sample homogenization prior to boiling. For tough samples like tissue or spores, combine mechanical disruption (e.g., bead beating) with the boiling step [19].

- Suboptimal Boiling Duration or Temperature: Verify the incubation time and temperature. Typical protocols use 95-100°C for 10-15 minutes. Use a calibrated heat block for consistent results [45].

- Insufficient Starting Material: Increase the sample input volume within the limits of the protocol, ensuring it does not exceed the buffer's capacity.

- Nuclease Degradation: Add chelating agents like EDTA (e.g., in TE buffer) to the boiling buffer to inhibit nucleases that may remain active after heating [19].

Problem: PCR Inhibition or Failure

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Carry-over of PCR Inhibitors: Boiling methods do not purify nucleic acids. Inhibitors like hemoglobin, polysaccharides, or ionic detergents can co-precipitate. Centrifuge the boiled sample at high speed (e.g., 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes) and use only the supernatant for downstream assays [44].

- Excessive Sample Background: For blood-contaminated samples, a pre-wash with PBS or a dilute detergent solution can reduce interference. Note that magnetic bead methods show superior resistance to hemoglobin inhibition [44].

- Inadequate Dilution: The crude nucleic acid extract may contain high levels of background. Perform a dilution series of the extract to find a concentration that minimizes inhibition in the PCR reaction.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Non-uniform Heating: Avoid using water baths, which can cause temperature gradients and cross-contamination. Use a calibrated digital dry bath or heat block [45].

- Improper Sample Handling: After boiling, briefly centrifuge the tube to collect all condensation before opening. Always pipette from the same consistent depth of the supernatant.

- Variability in Sample Lysis: Standardize the pre-boiling sample preparation step. For solid tissues, ensure uniform powdering under liquid nitrogen [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages and disadvantages of the boiling method compared to commercial column or bead-based kits?

A1: The boiling method is rapid, cost-effective, and technically straightforward, requiring minimal equipment. It is suitable for PCR-based screening in high-volume settings [45]. However, its main disadvantages are lower purity and higher susceptibility to inhibitors. Studies show that while the boiling method fails to detect HPV when hemoglobin concentration exceeds 30 g/L, magnetic bead methods remain effective even at 60 g/L [44]. Commercial kits provide higher purity nucleic acids, better consistency, and are more automation-friendly, but at a higher cost per sample and with longer processing times.

Q2: How can I improve the purity of my DNA obtained via a boiling protocol without switching to a column-based method?

A2: Several modifications can enhance purity:

- Use of Chelating Resins: Incorporating Chelex-100 resin in the boiling buffer significantly improves yield and purity by chelating metal ions that are cofactors for nucleases. One study on dried blood spots found that a Chelex boiling method yielded significantly higher DNA concentrations than several column-based kits [45].

- Optimized Buffers: Replacing simple water or TE buffer with a specialized buffer containing detergents (e.g., Tween 20) and chelating agents can improve lysis efficiency and nuclease inactivation [45].

- Post-Boiling Purification Steps: A simple alcohol precipitation or a clean-up with pre-made magnetic beads can be added to the protocol to remove contaminants without committing to a full commercial kit [6].

Q3: My downstream quantitative PCR (qPCR) results are variable when using crude boiling extracts. How can I improve reproducibility?

A3: Reproducibility is a known challenge with crude extracts. To improve it:

- Introduce an Internal Control: Spike a known amount of exogenous DNA or an internal amplification control into the sample before lysis. This allows you to distinguish between true target variation and inhibition or extraction inefficiency.

- Normalize Sample Input: Use a standardized metric for input material (e.g., cell count, tissue weight) rather than volume alone.

- Optimize Elution Volume: Consistently using a small, fixed elution volume (e.g., 50 µL) can increase the final DNA concentration and improve pipetting accuracy for downstream setup [45].

Q4: Are boiling methods suitable for RNA extraction?

A4: Boiling is generally not recommended for RNA extraction due to the high susceptibility of RNA to degradation by RNases. Most RNases are very heat-stable and can quickly degrade RNA upon cooling after the boil. RNA extraction requires specialized, RNase-inhibiting reagents and conditions. For rapid RNA extraction, dedicated commercial kits that include guanidinium thiocyanate-based lysis buffers are the preferred choice [46].

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies comparing boiling methods with other extraction techniques.

Table 1: Anti-Interference Performance against Hemoglobin (Simulated Blood Contamination)

| Hemoglobin Concentration (g/L) | Boiling Method (HPV Detection) | Magnetic Bead Method (HPV Detection) |

|---|---|---|

| 20 g/L | Positive | Positive |

| 30 g/L | Negative | Positive |

| 60 g/L | Negative | Positive |

Data adapted from a study comparing nucleic acid extraction methods for HPV genotyping. The magnetic bead method demonstrated significantly higher resistance to PCR inhibitors like hemoglobin [44].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of DNA Extraction Methods from Dried Blood Spots (DBS)

| Extraction Method | Relative DNA Yield (by qPCR) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Boiling with Chelex-100 Resin | Highest | Cost-effective, rapid, easy, suitable for large-scale studies [45] |

| Roche High Pure Column Kit | High | Significantly higher than other column kits [45] |

| QIAGEN QIAamp DNA Mini Kit | Low | Standardized but costly [45] |

| QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Low | Standardized but costly [45] |

| Boiling with TE Buffer | Not Reported | Simple but may yield lower purity [45] |

Table 3: Large-Scale HPV Detection Rate and Cost-Benefit Comparison

| Parameter | Boiling Method | Magnetic Bead Method |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Detection Rate | 10.02% | 20.66% |

| Cost Relative to Boiling | Baseline (0%) | +13.14% |

| Detection Rate Increase | Baseline (0%) | +106.19% |

Data from a longitudinal large-scale analysis (16,540 cases). The magnetic bead method, while slightly more expensive, provided a dramatically higher detection rate, making it highly cost-effective for clinical diagnostics [44].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Method: Chelex-100 Boiling Protocol for Dried Blood Spots

This protocol, optimized for DNA extraction from Dried Blood Spots (DBS), is noted for its high yield and cost-effectiveness [45].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Chelex-100 Resin: A chelating resin that binds metal ions, inactivating nucleases and improving DNA stability.

- PBS (Phosphate-Buffered Saline): A balanced salt solution used for washing and maintaining osmotic balance.

- Tween 20: A non-ionic detergent that aids in cell lysis and washing away impurities.

Procedure:

- Punch and Soak: Punch one 6 mm disk from the DBS and place it in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Add 1 mL of 0.5% Tween 20 solution in PBS.

- Overnight Incubation: Incubate the tube at 4°C for a minimum of 8 hours (e.g., overnight) to elute cells from the paper.

- Wash: Carefully remove and discard the Tween20 solution. Add 1 mL of pure PBS to the punch and incubate at 4°C for 30 minutes. After incubation, remove and discard the PBS.

- Chelex Boiling: Add 50 µL of a pre-heated 5% (w/v) Chelex-100 suspension to the punch. Pulse-vortex the mixture for 30 seconds.

- Heat Shock: Incubate the tube at 95°C for 15 minutes. During this incubation, pulse-vortex the tube briefly every 5 minutes.

- Pellet Debris: Centrifuge the tube at 11,000 x g for 3 minutes to pellet the Chelex beads and paper debris.

- Recover Supernatant: Carefully transfer the supernatant (containing the DNA) to a new microcentrifuge tube. For maximum recovery, the centrifugation and transfer steps can be repeated.

- Storage: Store the extracted DNA at -20°C until use. The DNA is suitable for direct use in PCR and qPCR [45].

Detailed Method: Standard Boiling Protocol for Cervical Swabs