Nucleic Acid Biosensing Platforms: A Comparative Review of Technologies from PCR to CRISPR and Beyond

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern biosensing platforms for nucleic acid detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Nucleic Acid Biosensing Platforms: A Comparative Review of Technologies from PCR to CRISPR and Beyond

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern biosensing platforms for nucleic acid detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of established and emerging technologies, including PCR, isothermal amplification, CRISPR-based systems, and Argonaute-powered detection. The review critically examines methodological workflows, real-world applications in pathogen detection and clinical diagnostics, and key optimization strategies for enhancing performance. A systematic comparative analysis evaluates sensitivity, specificity, cost, and portability to guide platform selection for specific research and development needs, offering insights into future directions for the field.

Core Principles and Evolution of Nucleic Acid Detection Technologies

Biosensors represent a powerful convergence of biological recognition and physicochemical detection, serving as indispensable tools in modern molecular diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety. The fundamental architecture of any biosensor rests upon a core triad: the recognition element that specifically binds the target analyte, the transducer that converts the biological binding event into a measurable signal, and the signal processor that interprets and displays this signal [1] [2]. In the specialized field of nucleic acid detection, the interplay among these three components dictates the overall performance, including sensitivity, specificity, cost, and suitability for point-of-care applications. This guide provides a structured comparison of biosensing platforms, focusing on the integration of novel bioreceptors with advanced transducer technologies to achieve ultra-sensitive and specific detection of nucleic acid targets. We summarize experimental data and detailed methodologies to offer researchers a clear framework for selecting and optimizing biosensor configurations for their specific applications.

The Biosensing Triad: Core Components and Functions

The performance of a nucleic acid biosensor is governed by the seamless integration of its three core components. Each plays a distinct yet interconnected role in the detection process.

Recognition Elements

The bioreceptor is the primary source of a biosensor's specificity. It is a biological or biomimetic element that recognizes and binds to the target nucleic acid sequence. Common recognition elements include:

- DNA Probes: Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) sequences complementary to a specific target are the most straightforward recognition elements. Hybridization between the probe and its target via Watson-Crick base pairing is the foundational mechanism [3] [4].

- Aptamers: These are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro through the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) process. They can fold into distinct three-dimensional structures that bind to specific targets, including proteins, small molecules, and even whole cells, with high affinity and specificity [5] [2] [6].

- CRISPR-crRNA: The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system, particularly with Cas12a and Cas13 proteins, utilizes a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) guide strand. This RNA molecule directs the Cas enzyme to a complementary nucleic acid target, triggering a specific binding event that often activates the enzyme's non-specific "collateral cleavage" activity, which is harnessed for signal amplification [7] [8].

Transducers

The transducer transforms the biorecognition event into a quantifiable physical signal. The choice of transducer directly impacts the sensor's sensitivity, detection limit, and potential for miniaturization [1]. The main categories are:

- Electrochemical Transducers: These measure electrical changes (current, potential, impedance) resulting from the nucleic acid hybridization or an associated enzymatic reaction. They are renowned for their high sensitivity, portability, and low cost [1] [2] [3].

- Optical Transducers: This class detects changes in light properties. Modalities include:

- Fluorescence: The most common readout for CRISPR-based assays, where the cleavage of a fluorescently-quenched ssDNA probe produces a fluorescent signal [8].

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Measures changes in the refractive index on a sensor surface upon target binding, allowing for label-free detection [2] [4].

- Colorimetric: Produces a visible color change, often suitable for simple, instrument-free readouts [5] [4].

- Mass-Sensitive Transducers: Devices like the Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) detect the change in mass on a sensor surface following target binding, which alters the resonant frequency of the crystal [2].

Signal Processors

This component encompasses the electronics and software required to process, amplify, and display the raw signal from the transducer. Advancements in this area have enabled the development of portable, user-friendly devices with digital readouts, smartphone integration, and cloud-based data analysis, which are crucial for point-of-care diagnostics [1] [3].

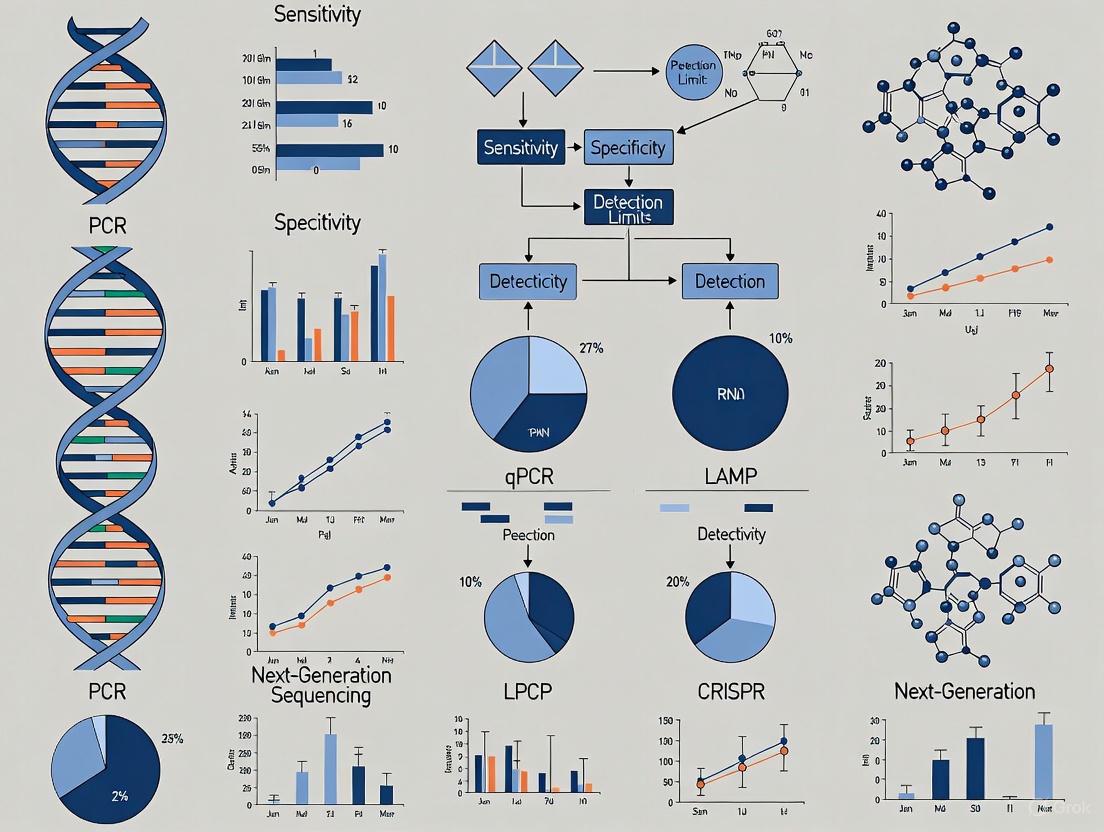

The relationship between these core components and their role in nucleic acid detection is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: The core workflow of a biosensor, showcasing the "Biosensing Triad."

Comparative Analysis of Biosensing Platforms

The combination of different recognition elements and transducers creates distinct biosensing platforms, each with unique advantages and limitations. The following table provides a direct comparison of the leading technologies for nucleic acid detection.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Nucleic Acid Biosensing Platforms

| Platform | Recognition Element | Transducer Type | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Assay Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-based Sensors [5] [4] | DNA Primers | Optical (Fluorescence, Colorimetric) | ~63 aM – 2×10³ copies/μL [5] | 1-3 hours | Gold standard for sensitivity; high specificity; quantitative | Requires thermal cycling; bulky equipment; risk of carryover contamination |

| Electrochemical Genosensors [2] [3] | DNA Probe | Electrochemical (Amperometric, Potentiometric) | fM – pM range [3] | 15-60 mins | High sensitivity; portable; low cost; low power requirement | Susceptible to non-specific adsorption; requires redox labels in some designs |

| Aptamer-based Sensors [5] [6] | Aptamer | Optical / Electrochemical | pM – nM range (for proteins) [5] | 30-90 mins | Wide target range (ions, proteins, cells); high stability; reusability | SELEX process for aptamer development is complex and time-consuming |

| CRISPR-based Biosensors [7] [8] | crRNA + Cas protein | Optical (Fluorescence, Colorimetric) | aM – fM range [8] | 15-60 mins | Single-base specificity; high sensitivity; room temperature operation | crRNA can be degraded by RNases; requires pre-amplification for low-abundance targets |

Experimental Protocols for Key Biosensing Platforms

To facilitate practical implementation, this section outlines detailed experimental protocols for two high-performance biosensing platforms: the CRISPR-Cas12a system and the electrochemical genosensor.

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas12a-mediated Fluorescent Detection of DNA

This protocol leverages the target-activated non-specific single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) cleavage (trans-cleavage) activity of the Cas12a protein for highly specific nucleic acid detection [8].

1. Principle: A guide RNA (crRNA) complexes with the Cas12a enzyme. Upon recognizing its complementary double-stranded DNA target, the Cas12a complex becomes activated. This activated state triggers the collateral cleavage of a nearby fluorophore-quencher labeled ssDNA reporter probe. The cleavage separates the fluorophore from the quencher, generating a fluorescent signal proportional to the amount of target DNA [8].

2. Workflow:

The step-by-step experimental workflow is visualized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Workflow for CRISPR-Cas12a fluorescent detection.

3. Materials and Reagents:

- Cas12a Enzyme: The effector protein that provides the cleavage activity.

- crRNA: Custom-designed RNA guide strand complementary to the target DNA sequence.

- ssDNA Reporter Probe: A short ssDNA oligonucleotide labeled with a fluorophore (e.g., FAM) at one end and a quencher (e.g., BHQ1) at the other.

- Reaction Buffer: Typically containing HEPES, MgCl₂, and DTT to maintain optimal enzyme activity.

- Nucleic Acid Amplification Reagents: For pre-amplification of the target via RPA or LAMP if detecting low-copy targets [7] [8].

4. Procedure:

- Pre-amplification (Optional but common): Amplify the target DNA from the sample using an isothermal amplification method like Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) or Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) to enhance detection sensitivity.

- Assay Setup: In a reaction tube, combine the following:

- 50 nM Cas12a enzyme

- 50 nM target-specific crRNA

- 500 nM fluorescent ssDNA reporter probe

- 1X Cas12a reaction buffer

- The amplicon from step 1 or the native target DNA.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C for 15-60 minutes.

- Signal Detection: Measure the fluorescence intensity using a plate reader, a portable fluorometer, or even a blue light transilluminator for visual assessment. The increase in fluorescence over a no-target control confirms the presence of the target.

Protocol: Electrochemical DNA Sensor for Pathogen Detection

This protocol describes the construction of a label-free electrochemical genosensor for detecting specific bacterial DNA sequences, such as from Acinetobacter baumannii [3].

1. Principle: A single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) capture probe is immobilized on an electrode surface. When a complementary target DNA strand hybridizes with the capture probe, it alters the interfacial properties of the electrode. This change can be measured as a shift in electrochemical parameters, such as the oxidation current of intrinsic guanine bases or overall electrochemical impedance [3].

2. Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in fabricating and using the electrochemical genosensor.

Diagram 3: Workflow for an electrochemical DNA sensor.

3. Materials and Reagents:

- Capture Probe: A thiol- or amino-modified ssDNA sequence specific to the target pathogen.

- Working Electrode: Gold, glassy carbon, or screen-printed carbon electrodes.

- Electrochemical Probe: A redox couple such as [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in solution.

- Surface Linkers: Chemicals like chitosan or cysteamine for probe immobilization [3].

- Electrochemical Workstation: A potentiostat for applying potentials and measuring current/impedance.

4. Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Clean the working electrode thoroughly. For a gold electrode, incubate it with a solution of thiolated capture probes to form a self-assembled monolayer on the electrode surface. Block any remaining bare surface sites with a passivating agent like 6-mercapto-1-hexanol to minimize non-specific binding.

- Hybridization: Inject the sample containing the target DNA onto the modified electrode surface. Incubate for a set time (e.g., 30 minutes) under controlled temperature to allow for hybridization to occur.

- Washing: Rinse the electrode with a buffer to remove any unbound or weakly adsorbed DNA.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Immerse the electrode in a solution containing the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe. Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV). The hybridization event will cause a measurable increase in charge transfer resistance (in EIS) or a decrease in the redox current (in DPV) due to the repulsion of the negatively charged redox probe by the DNA backbone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development of a nucleic acid biosensor requires a carefully selected set of reagents and materials. The following table catalogs the key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) Probes [3] [4] | The foundational recognition element; used as capture probes in genosensors and primers in amplification. |

| Aptamers [5] [6] | Synthetic oligonucleotide receptors for a wide range of targets beyond nucleic acids; offer high stability. | |

| crRNA for CRISPR Systems [7] [8] | Provides sequence specificity for Cas enzymes (e.g., Cas12a, Cas13); the key to programmable detection. | |

| Signal Amplification | Taq DNA Polymerase [5] [4] | Enzyme for PCR-based target pre-amplification; essential for achieving high sensitivity. |

| Bst Polymerase [5] | DNA polymerase for isothermal amplification methods like LAMP; enables rapid detection at constant temperature. | |

| Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Kit [7] [8] | For isothermal pre-amplification of target DNA; often coupled with CRISPR assays for ultra-sensitive detection. | |

| Transduction & Materials | Screen-printed Carbon Electrodes [3] | Low-cost, disposable electrodes for electrochemical biosensors; ideal for point-of-care device development. |

| Fluorophore-Quencher Pairs (FAM/BHQ1) [8] | Used to label reporter molecules in fluorescent assays (e.g., CRISPR, molecular beacons). | |

| Gold Nanoparticles [2] | Used in colorimetric assays and for enhancing signal in electrochemical and SPR-based biosensors. | |

| Low-dimensional Materials (Graphene, MoS₂) [4] | Used to modify electrode surfaces; enhance electrical conductivity and surface area for improved sensitivity. |

Quantitative analysis of nucleic acids is fundamental to molecular biology research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. Among the most established technologies for this purpose are polymerase chain reaction (PCR), quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), and microarray platforms. These conventional workhorses have enabled groundbreaking discoveries across life sciences by allowing researchers to detect, quantify, and profile genetic material with increasing sophistication. PCR revolutionized molecular biology by enabling exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences, while qPCR added real-time quantification capabilities through fluorescent detection systems. Microarray technology further expanded these capabilities to allow parallel analysis of thousands to millions of genetic elements simultaneously, facilitating genome-wide expression profiling and genotyping studies [9] [10].

Despite the emergence of next-generation sequencing technologies, these established methods remain widely used due to their proven reliability, cost-effectiveness for targeted studies, and standardized protocols that have been optimized over decades. Each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different experimental scenarios, from targeted gene expression validation to large-scale screening applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of PCR, qPCR, and microarray technologies, supported by experimental data and implementation frameworks to help researchers select the most appropriate platform for their specific nucleic acid detection needs.

PCR and qPCR Fundamentals

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a fundamental molecular biology technique that enables exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences through repeated temperature cycling. The basic PCR process involves three main steps per cycle: denaturation (separating DNA strands at high temperature), annealing (allowing primers to bind to complementary sequences at lower temperature), and elongation (extending the primers with a DNA polymerase). Conventional PCR provides semi-quantitative results typically analyzed by gel electrophoresis, where band intensity indicates amplification success [11].

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, represents an advanced evolution of this technology that enables monitoring of the amplification process in real time through fluorescent detection systems. In qPCR, the accumulation of PCR products is measured during each cycle rather than at the endpoint, allowing for precise quantification of the initial DNA template. Two main fluorescence detection chemistries are commonly used: DNA-intercalating dyes (e.g., SYBR Green) that fluoresce when bound to double-stranded DNA, and sequence-specific probes (e.g., TaqMan probes, molecular beacons) that provide higher specificity through hybridization to specific target sequences [12] [11]. The critical measurement in qPCR is the cycle threshold (Ct), which represents the amplification cycle at which fluorescence crosses a predetermined threshold, correlating inversely with the initial template concentration [13].

Microarray Technology Principles

Microarray technology operates on fundamentally different principles than PCR-based methods. Microarrays consist of high-density arrays of microscopic spots containing nucleic acid probes immobilized on a solid surface, typically a glass slide or silicon chip. Each probe is designed to be complementary to a specific target sequence of interest. In a typical microarray experiment, fluorescently labeled sample DNA or RNA is hybridized to the array, and the resulting hybridization pattern is quantified using laser scanning and fluorescence detection [14] [15].

The two primary microarray formats are expression arrays for profiling gene expression levels and genotyping arrays for detecting genetic variations. Expression arrays measure the abundance of thousands of transcripts simultaneously, while genotyping arrays detect single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and copy number variations (CNVs) across the genome. The resolution and coverage of microarrays depend on the number of features (probes) included, with modern arrays containing millions of features to comprehensively cover genomes or transcriptomes [14]. Unlike PCR, microarrays do not amplify the target molecules but rather rely on the specificity of hybridization between the probe and its complementary sequence in the sample.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Technical Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance Characteristics Comparison of Nucleic Acid Detection Technologies

| Parameter | PCR | qPCR | Microarray |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (single targets) | Medium (up to 30 targets) | High (thousands to millions of targets) |

| Sensitivity | Moderate (semi-quantitative) | High (can detect single copies) | Moderate (limited by hybridization efficiency) |

| Dynamic Range | Limited (end-point detection) | Wide (7-8 logs) | Narrow (3-4 logs) |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative (relative) | Absolute or relative | Relative (compared to reference) |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low (typically single-plex) | Medium (limited by detection channels) | High (thousands of simultaneous assays) |

| Typical Applications | Target amplification, cloning | Gene expression, pathogen detection | Genome-wide expression profiling, CNV analysis |

| Cost per Sample | Low | Low to medium | Medium to high |

Experimental data from direct comparisons between these technologies provides valuable insights into their relative performance. A comprehensive study comparing six different microarray platforms from leading vendors demonstrated significant variation in sensitivity and specificity for detecting copy number variants (CNVs). The NimbleGen 2.1M platform showed superior accuracy and precision in copy number dosage estimates, while Illumina and Affymetrix platforms leveraged single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) information to compensate for limitations in dosage estimation [14].

In a clinical application study comparing qPCR and microarray platforms for respiratory virus detection, researchers found that both methods yielded concordant results for 94.1% of specimens from 221 children hospitalized with respiratory tract infections. The microarray system demonstrated advantage in multiplexing capability, detecting 23 different respiratory viruses simultaneously compared to the qPCR panel. However, qPCR maintained advantages in sensitivity for low-abundance targets and established reliability for quantitative applications [16].

Economic and Practical Considerations

Table 2: Economic and Practical Considerations for Nucleic Acid Detection Platforms

| Consideration | qPCR | Microarray | RNA-Seq (for context) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment Cost | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | High |

| Reagent Cost per Sample | Low (especially for few targets) | Moderate | High |

| Data Complexity | Low (manageable datasets) | Moderate (requires specialized analysis) | High (advanced bioinformatics essential) |

| Hands-on Time | Low to moderate | Moderate | Low (after library preparation) |

| Technical Expertise Required | Basic molecular biology | Moderate bioinformatics | Advanced bioinformatics |

| Sample Throughput | High (especially with 384-well plates) | Moderate to high | Moderate |

| Break-even Point (vs. RNA-Seq) | Cost-effective for <30 targets | Varies by project scale | More economical for whole transcriptome |

When evaluating cost considerations, studies have shown that qPCR remains the most economical choice for projects involving a limited number of targets (typically up to 30 genes), while microarrays provide better value for genome-scale analyses where sequencing costs would be prohibitive [17] [15]. The dynamic range of qPCR significantly exceeds that of microarrays, with qPCR capable of detecting over 7 orders of magnitude of template concentration compared to approximately 3-4 orders of magnitude for most microarray platforms [15]. This makes qPCR particularly valuable for applications requiring precise quantification across widely varying expression levels, such as in pathogen load determination or validation of differentially expressed genes.

Microarrays offer superior multiplexing capacity, enabling simultaneous analysis of thousands to millions of genetic features in a single experiment. However, this advantage comes with limitations in detecting novel sequences, as microarrays are restricted to pre-designed probes based on known genomic information [10] [15]. Additionally, microarray data are more susceptible to cross-hybridization artifacts and typically require more sophisticated normalization procedures than qPCR data.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

qPCR Experimental Workflow

qPCR Experimental Workflow with Quality Control

A rigorous qPCR experiment requires careful attention to each step of the workflow. The process begins with proper sample collection and preservation to maintain RNA integrity. Following nucleic acid extraction, RNA quality and quantity should be assessed using spectrophotometric or microfluidic methods. Reverse transcription converts RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) using either random hexamers, oligo-dT primers, or gene-specific primers, with choice of method impacting results [18] [11].

The qPCR reaction setup involves preparation of a master mix containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, primers, probe (if using probe-based chemistry), and buffer components. Critical experimental considerations include determining optimal primer concentrations, validating amplification efficiency through standard curves, and including appropriate controls (no-template controls, reverse transcription controls, inter-run calibrators). Thermal cycling parameters must be optimized for each assay, with typical protocols involving an initial activation step (e.g., 95°C for 2-10 minutes) followed by 40-50 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 10-30 seconds), annealing (primer-specific temperature for 15-60 seconds), and extension (often combined with annealing) [13] [11].

Data analysis requires appropriate normalization strategies, with the 2−ΔΔCT method being widely used but potentially problematic when amplification efficiencies deviate from ideal [13]. The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring qPCR experimental rigor and reproducibility [13] [18]. Recent advances in normalization approaches include using stable combinations of reference genes identified from RNA-Seq databases rather than relying on traditional housekeeping genes, which may exhibit variable expression under different experimental conditions [18].

Microarray Experimental Protocol

Microarray Experimental Workflow

Microarray experiments begin with careful experimental design to ensure appropriate sample size, replication, and blocking to account for technical variability. For gene expression studies, RNA is extracted and converted to cDNA, which is then labeled with fluorescent dyes (typically Cy3 and Cy5 for two-color arrays or a single dye for one-color platforms). For array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) applications, test and reference DNA samples are differentially labeled with fluorescent dyes and co-hybridized to the array [14] [16].

The hybridization process is a critical step where labeled targets are applied to the microarray surface under controlled conditions to allow specific binding to complementary probes. Following hybridization, extensive washing removes non-specifically bound material, and the array is scanned using a high-resolution fluorescence scanner. The resulting images are processed to extract fluorescence intensity values for each probe feature, which must undergo quality control assessment to identify artifacts, background correction, and normalization to account for technical variability [14].

Data analysis employs statistical methods to identify significant differences between experimental conditions, with false discovery rate correction for multiple testing being essential due to the large number of simultaneous comparisons. For aCGH data, segmentation algorithms or hidden Markov models are typically applied to identify genomic regions with significant copy number alterations [14]. The availability of well-established bioinformatics tools and pipelines for microarray data analysis lowers the barrier for implementation compared to newer sequencing technologies [15].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nucleic Acid Detection Technologies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technology | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Enzymatic amplification of DNA targets | PCR, qPCR | Thermal stability, fidelity, processivity |

| Fluorescent Probes/Dyes | Detection of amplified products | qPCR | Specificity, quenching efficiency, spectral properties |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Conversion of RNA to cDNA | qRT-PCR, Microarray | Processivity, template specificity, inhibition resistance |

| Nucleic Acid Probes | Target capture and detection | Microarray | Specificity, melting temperature, cross-hybridization potential |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for DNA synthesis | PCR, qPCR, Microarray | Purity, concentration, freeze-thaw stability |

| Primers | Target-specific amplification | PCR, qPCR | Specificity, secondary structure, melting temperature |

| Hybridization Buffers | Facilitate probe-target binding | Microarray | Stringency, hybridization efficiency, background minimization |

| Normalization Controls | Data standardization across experiments | qPCR, Microarray | Expression stability, experimental invariance |

The selection of appropriate reagents is critical for successful nucleic acid detection experiments. For qPCR applications, polymerase selection significantly impacts amplification efficiency and specificity. Modern hot-start polymerases prevent non-specific amplification during reaction setup, while specialized enzymes maintain activity through challenging secondary structures. Fluorescence chemistry selection represents another crucial consideration—SYBR Green offers cost-effectiveness and simplicity but requires careful validation of specificity via melt curve analysis, while probe-based methods (e.g., TaqMan, molecular beacons) provide enhanced specificity through dual recognition (primers plus probe) but at higher cost and with more complex assay design requirements [13] [11].

For microarray applications, labeling efficiency directly impacts sensitivity and dynamic range. Direct labeling methods incorporate modified nucleotides during cDNA synthesis, while indirect approaches use hapten-labeled nucleotides followed by fluorescent antibody detection. Hybridization buffers must be optimized to maximize specific binding while minimizing non-specific background, with chemical additives (e.g., formamide, blocking agents) often included to enhance stringency [14] [16]. Quality control metrics for both qPCR and microarray experiments should include assessment of RNA integrity, cDNA synthesis efficiency, hybridization consistency, and amplification efficiency to ensure data reliability [13] [18].

Recent innovations in reference gene selection have demonstrated that stable combinations of non-stable genes can outperform traditional housekeeping genes for qPCR data normalization. This approach uses comprehensive RNA-Seq databases to identify gene combinations whose expression balances across experimental conditions, providing more reliable normalization than single reference genes [18].

Implementation Guide and Decision Framework

Technology Selection Guidelines

Choosing between PCR, qPCR, and microarray technologies depends on multiple factors, including experimental objectives, scale, budget, and available expertise. qPCR is the preferred choice when studying a limited number of targets (typically <30), when precise quantification is required across a wide dynamic range, when sample material is limited, or when cost constraints are significant [15]. Its status as the "gold standard" for nucleic acid quantification makes it ideal for validation studies and clinical applications requiring regulatory approval.

Microarray technology excels in discovery-phase research where the goal is comprehensive profiling without prior knowledge of specific targets of interest. Its ability to simultaneously analyze thousands of genes makes it valuable for biomarker discovery, pathway analysis, and large-scale screening applications [10] [15]. Established bioinformatics pipelines and lower computational requirements compared to sequencing technologies make microarrays accessible to laboratories with limited bioinformatics support.

The emergence of digital PCR (dPCR) as a third-generation PCR technology offers enhanced sensitivity and absolute quantification without standard curves, making it particularly valuable for detecting rare mutations, copy number variation analysis, and liquid biopsy applications [9] [12]. While not the focus of this guide, dPCR represents an important evolution in PCR technology with growing applications in both research and clinical settings.

Future Outlook and Complementary Technologies

While PCR, qPCR, and microarrays remain essential tools in molecular biology, they increasingly exist within a broader technological landscape that includes next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms. RNA-Seq in particular offers advantages in discovering novel transcripts, detecting sequence variations, and providing a broader dynamic range than microarrays [10] [15]. However, sequencing technologies come with higher costs, greater computational requirements, and more complex data analysis challenges [17] [15].

The most effective research strategies often combine these technologies, using microarrays for initial discovery and qPCR for validation of key findings. This integrated approach leverages the strengths of each platform while mitigating their individual limitations. As the field continues to evolve, technological advances in microfluidics, multiplexing, and detection chemistries are further enhancing the capabilities of these established workhorses, ensuring their continued relevance in the molecular diagnostics and research landscape [11].

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte. The transduction mechanism represents the core functionality that converts molecular recognition events into quantifiable signals, forming the critical link between biological interaction and analytical measurement. In nucleic acid detection research, the choice of transduction mechanism directly impacts key performance parameters including sensitivity, specificity, analysis time, and instrumentation requirements [19].

The three principal transduction platforms—optical, electrochemical, and mass-based—each operate on distinct physical principles and offer complementary advantages for different research and diagnostic scenarios. Optical biosensors detect changes in light properties resulting from bio-recognition events, while electrochemical biosensors monitor electrical signals generated from redox reactions at functionalized electrode surfaces. Mass-based biosensors, conversely, detect mass changes on sensor surfaces through frequency variations in piezoelectric crystals [19]. Understanding the fundamental operating principles, capabilities, and limitations of each transduction mechanism is essential for researchers selecting appropriate platforms for specific nucleic acid detection applications in both clinical and research settings.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Specifications

The operational characteristics of biosensing platforms vary significantly across transduction mechanisms, with each technology exhibiting distinct strengths for particular application scenarios. The following comparison outlines the fundamental working principles and key technical differentiators.

Table 1: Fundamental Principles of Major Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms

| Transduction Mechanism | Working Principle | Measured Signal | Key Recognition Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical | Detection of changes in light properties | Light intensity, wavelength, polarization, phase | Antibodies, aptamers, nucleic acids [20] [21] |

| Electrochemical | Measurement of electrical changes from redox reactions | Current, potential, impedance, conductance | Enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, DNA [19] [22] |

| Mass-Based | Detection of mass changes on sensor surface | Frequency, phase shift | Antibodies, DNA, synthetic receptors [19] |

Optical Transduction Mechanisms

Optical biosensors function by detecting modifications in light properties resulting from binding events between target analytes and recognition elements immobilized on sensor surfaces. These platforms offer exceptional sensitivity and versatility through multiple detection modalities including fluorescence, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), chemiluminescence, and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) [20] [21].

Fluorescence-based sensors typically employ fluorophore-labeled probes whose emission intensity, polarization, or spectral characteristics change upon target binding. Advanced fluorescence formats utilize Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), where energy transfer occurs between donor and acceptor molecules within 1-10 nm distances, leading to measurable fluorescence quenching or recovery [21]. Graphene oxide (GO) has emerged as a particularly effective quencher in FRET-based nucleic acid sensors due to its exceptional photoelectric properties and strong π–π stacking interactions with single-stranded DNA [21].

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) platforms detect refractive index changes near metal surfaces (typically gold) when target molecules bind to immobilized probes, enabling label-free detection in real-time. SERS-based sensors utilize plasmonic nanostructures to significantly enhance Raman scattering signals, providing vibrational "fingerprints" for highly specific identification with single-molecule sensitivity potential [23] [24]. Recent innovations in SERS substrates include anisotropic gold nanostructures, cellulose-gold nanocomposites, and close-packed nanocube assemblies that further enhance detection capabilities [23].

Figure 1: Optical biosensing workflow showing multiple detection pathways including fluorescence, SPR, SERS, colorimetric, and chemiluminescence approaches.

Electrochemical Transduction Mechanisms

Electrochemical biosensors measure electrical signals generated from redox reactions occurring at biologically functionalized electrode surfaces. These platforms have gained significant research attention due to their high sensitivity, miniaturization potential, low cost, and compatibility with point-of-care applications [19] [20] [22]. The working principle involves the immobilization of biological recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, or DNA) on electrode surfaces, where binding events subsequently alter electrochemical properties measurable as current, potential, or impedance changes.

Amperometric sensors represent the most common electrochemical format, measuring current generated from oxidation/reduction reactions at a constant applied potential. Potentiometric sensors detect potential differences at electrode-electrolyte interfaces under zero-current conditions, while impedimetric sensors monitor changes in surface conductivity and charge transfer resistance resulting from binding events [20]. Electrochemical genosensors specifically designed for nucleic acid detection utilize immobilized single-stranded DNA probes to hybridize with complementary targets, with signal transduction achieved through electroactive labels or label-free charge variation detection [22].

Recent innovations in electrochemical biosensing include nanotechnology-enhanced interfaces using materials such as gold nanoparticles, molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), and graphene-based composites that significantly improve electron transfer efficiency and bioreceptor immobilization capacity [24] [22]. These advanced materials have enabled the development of ultrasensitive platforms capable of detecting nucleic acid biomarkers at femtomolar concentrations, making them particularly valuable for early cancer diagnosis and pathogen detection [24] [22].

Figure 2: Electrochemical biosensing mechanism showing different measurement approaches including amperometric, potentiometric, impedimetric, and conductometric methods.

Mass-Based Transduction Mechanisms

Mass-based biosensors, often utilizing piezoelectric crystals such as quartz crystal microbalances (QCM), detect mass changes occurring on sensor surfaces through corresponding frequency or phase variations [19]. These platforms operate on the principle that the resonant frequency of a piezoelectric crystal decreases proportionally to mass increases on its surface, enabling highly sensitive detection of binding events without requiring labeling.

The label-free nature of mass-based detection provides significant advantages for monitoring biomolecular interactions in real-time, allowing researchers to obtain kinetic data and binding affinity measurements. These systems typically immobilize biological recognition elements (antibodies, DNA probes, or synthetic receptors) on the crystal surface, where subsequent target binding increases the mass load and generates measurable frequency shifts [19]. While less commonly implemented in point-of-care settings compared to optical and electrochemical alternatives, mass-based biosensors offer robust performance for laboratory-based nucleic acid detection and characterization applications.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Direct comparison of biosensing platforms requires evaluation across multiple performance parameters to determine optimal implementation scenarios. The following tables summarize key operational characteristics and recently reported experimental data for each transduction mechanism.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Biosensing Transduction Mechanisms

| Parameter | Optical | Electrochemical | Mass-Based |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Very High (fM-aM) | High (fM) | Moderate-High (pM-nM) |

| Selectivity | Excellent | Very Good | Good |

| Multiplexing Capability | High | Moderate | Low |

| Analysis Time | Minutes-Hours | Minutes | Minutes-Hours |

| Sample Volume | µL-mL | µL-nL | µL-mL |

| Instrument Cost | High | Low-Moderate | Moderate-High |

| Ease of Miniaturization | Moderate | Excellent | Moderate |

| Real-time Monitoring | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 3: Recent Experimental Performance Data for Nucleic Acid Detection

| Transduction Mechanism | Target | Linear Range | Limit of Detection | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | Fumonisin B1 | 0.5-20 ng/mL | 0.15 ng/mL | Mycotoxin detection [21] |

| Electrochemical | BRCA-1 protein | 0.05-20 ng/mL | 0.04 ng/mL | Cancer biomarker [24] |

| Electrochemical | Glucose | 10 μM-7.0 mM | 1 μM | Metabolic monitoring [24] |

| SERS | Malachite Green | - | 3.5×10⁻³ mg/L | Environmental contaminant [24] |

| Electrochemical | miRNA-34a | - | - | Alzheimer's diagnosis [19] |

| Electrochemical Genosensor | Various nucleic acids | - | fM levels | Viral/cancer detection [22] |

Recent research demonstrates that electrochemical biosensors modified with nanomaterials achieve exceptional sensitivity for nucleic acid detection. Graphene–quantum dot hybrid biosensors have demonstrated femtomolar (fM) sensitivity through charge transfer-based quenching mechanisms, enabling detection limits as low as 0.1 fM for biotin–streptavidin and IgG–anti-IgG interactions [24]. Similarly, gold nanoparticle/molybdenum disulfide composites have enabled BRCA-1 protein detection at 0.04 ng/mL, highlighting the clinical potential of these platforms for cancer diagnostics [24].

Metal nanocluster-based biosensors represent an emerging technology with unique optical and electrochemical properties. Gold, silver, and copper nanoclusters provide strong photoluminescence, high photochemical stability, and excellent catalytic activity, enhancing sensitivity and selectivity for pathogen detection applications [25]. These ultra-small nanoclusters exhibit quantum confinement effects that generate distinctive optical behavior compared to larger nanoparticles, making them particularly valuable for fluorescence-based nucleic acid detection schemes [25].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fluorescence Aptasensor Protocol for Nucleic Acid Detection

Principle: This protocol utilizes a nuclease-triggered "signal-on" fluorescent biosensor with signal amplification for highly sensitive nucleic acid detection, adapted from mycotoxin detection methodologies [21].

Materials:

- Carboxy-X-rhodamine (ROX)-labeled aptamer sequence

- Graphene oxide (GO) suspension

- Target nucleic acid sequence

- Nuclease enzyme

- Appropriate buffer solution (pH optimized for aptamer binding)

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Prepare the ROX-labeled aptamer solution in appropriate buffer at optimal concentration.

- Add GO suspension to the aptamer solution and incubate for 15-30 minutes to allow π–π stacking interactions, resulting in fluorescence quenching.

- Introduce the target nucleic acid sample and incubate for 30-60 minutes to facilitate aptamer-target binding, which induces conformational changes and separates ROX from GO surface, restoring fluorescence.

- Add nuclease enzyme to digest the aptamer-target complex, releasing the target and causing ssDNA and ROX to re-adsorb onto GO, resulting in secondary fluorescence quenching.

- Measure fluorescence intensity at excitation/emission wavelengths specific to ROX (approximately 580/605 nm).

- Calculate target concentration based on fluorescence recovery relative to calibration standards.

Key Considerations:

- Optimize GO concentration to maximize quenching efficiency while maintaining assay reproducibility.

- Control nuclease digestion time to balance signal amplification against background noise.

- Include appropriate controls (non-complementary sequences) to verify binding specificity.

Electrochemical Genosensor Protocol for DNA Hybridization Detection

Principle: This protocol details the development of a nucleic acid-based electrochemical biosensor for sequence-specific DNA detection using electrode-immobilized capture probes [22].

Materials:

- Thiol- or amino-modified DNA capture probes

- Gold or carbon electrode surfaces

- Molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) and gold nanoparticle (AuNP) nanocomposites

- Methylene blue or other electrochemical indicators

- Electrochemical workstation with three-electrode configuration

- Buffer solutions for hybridization and washing

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification:

- Prepare nanocomposite of MoS₂ and AuNPs in chitosan solution.

- Deposit nanocomposite onto clean electrode surface and allow to dry.

- Characterize modified surface using cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Probe Immobilization:

- Incubate modified electrode with thiolated DNA capture probes for 12-16 hours at controlled temperature.

- Rinse thoroughly to remove non-specifically adsorbed probes.

- Treat with 6-mercapto-1-hexanol to passivate uncovered electrode areas.

Hybridization and Detection:

- Incubate probe-functionalized electrode with target DNA sample for 30-60 minutes under optimized hybridization conditions.

- Wash electrode to remove non-specifically bound sequences.

- Transfer to electrochemical cell containing appropriate buffer and redox indicator.

- Perform differential pulse voltammetry or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements.

- Quantify hybridization through changes in current response or charge transfer resistance.

Key Considerations:

- Optimize probe density on electrode surface to minimize steric hindrance while maximizing hybridization efficiency.

- Control hybridization temperature and ionic strength to ensure sequence specificity.

- Implement rigorous washing procedures to minimize non-specific adsorption effects.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of biosensing platforms requires specific reagents and materials optimized for each transduction mechanism. The following table details essential components and their functions in nucleic acid detection assays.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensing Applications

| Category | Specific Material | Function | Compatible Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles | Signal amplification, electron transfer enhancement | Electrochemical, Optical [24] |

| Graphene oxide | Fluorescence quenching, large surface area | Fluorescence, Electrochemical [21] | |

| Molybdenum disulfide | Electron transfer facilitation | Electrochemical [24] | |

| Metal nanoclusters (Au, Ag, Cu) | Fluorescence, catalytic activity | Optical, Electrochemical [25] | |

| Biological Elements | Nucleic acid aptamers | Target recognition | Optical, Electrochemical [21] [22] |

| DNA/RNA probes | Sequence-specific hybridization | Optical, Electrochemical, Mass-based [22] | |

| Antibodies | Protein biomarker recognition | Optical, Electrochemical, Mass-based [19] | |

| Signal Elements | Enzymes (HRP, GOx) | Signal generation through catalysis | Electrochemical, Optical [24] |

| Fluorophores (FAM, ROX) | Light emission for detection | Fluorescence [21] | |

| Electroactive labels | Electron transfer for detection | Electrochemical [22] | |

| Platform Materials | Piezoelectric crystals | Mass sensing element | Mass-based [19] |

| Gold films | SPR substrate | Optical [20] | |

| Screen-printed electrodes | Low-cost sensing platforms | Electrochemical [19] |

The comparative analysis of optical, electrochemical, and mass-based transduction mechanisms reveals a dynamic biosensing landscape where technology selection depends heavily on specific application requirements. Optical platforms provide exceptional sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities ideal for laboratory-based nucleic acid analysis, while electrochemical systems offer superior miniaturization potential and cost-effectiveness for point-of-care diagnostics. Mass-based sensors deliver valuable label-free interaction data for binding kinetics studies.

Future development trajectories indicate increasing convergence of these technologies with advanced nanomaterials, microfluidics, and artificial intelligence to create next-generation biosensing platforms [19] [25]. The integration of machine learning algorithms with SERS-based detection exemplifies this trend, enhancing analytical accuracy for complex sample analysis [23]. Similarly, the development of multimodal sensors combining complementary transduction mechanisms addresses limitations inherent to individual platforms, potentially enabling unprecedented sensitivity and reliability in nucleic acid detection [24].

As biosensing technologies continue evolving, researchers should consider application-specific requirements including sensitivity thresholds, sample complexity, operational environment, and implementation costs when selecting appropriate transduction mechanisms. The ongoing innovation across all platform categories promises to further expand analytical capabilities, ultimately advancing both fundamental research and clinical diagnostics in nucleic acid analysis.

Platform Methodologies and Their Translational Applications

CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR Systems for Viral Pathogen Identification

CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR (DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter) has emerged as a transformative biosensing platform for viral pathogen identification, offering a powerful alternative to traditional nucleic acid detection methods. This technology leverages the unique properties of the Cas12a enzyme, which exhibits collateral cleavage activity upon recognition of specific viral DNA sequences [26] [27]. The DETECTR system represents a paradigm shift in molecular diagnostics, combining exceptional sensitivity with rapid detection capabilities that make it particularly valuable for point-of-care testing and epidemic response [28] [27]. As researchers and drug development professionals increasingly seek robust detection platforms, understanding the comparative performance of CRISPR-Cas12a against other biosensing technologies becomes essential for advancing diagnostic applications across viral pathogens including SARS-CoV-2, HPV, and African swine fever virus [27].

The fundamental innovation of Cas12a lies in its dual enzymatic activities: sequence-specific cis-cleavage of target DNA and non-specific trans-cleavage of single-stranded DNA reporters upon target recognition [27] [29]. This mechanism enables the conversion of specific viral nucleic acid sequences into amplified, detectable signals without requiring complex instrumentation [26]. When framed within the broader context of biosensing platforms for nucleic acid detection research, CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR occupies a strategic position between traditional PCR-based methods and emerging CRISPR-based alternatives, offering a balance of sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation advantages [27] [30].

Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas12a Activation and Detection

The CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR system functions through a precisely orchestrated molecular mechanism that converts target recognition into detectable signals. Understanding this mechanism is fundamental to appreciating its applications in viral pathogen detection.

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas12a Activation and Detection Mechanism. The crRNA guides the Cas12a enzyme to target viral DNA containing a TTTV PAM sequence. Upon recognition and binding, the activated Cas12a exhibits trans-cleavage activity, indiscriminately cutting single-stranded DNA FQ reporters and generating a detectable fluorescence signal.

The core detection mechanism begins with the formation of a ribonucleoprotein complex between the Cas12a enzyme and a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) guide sequence [26]. This complex scans DNA molecules for a specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence—typically 5'-TTTV-3' for most Cas12a orthologs—which serves as the initial recognition site [26] [27]. Once the PAM site is identified, the crRNA interrogates adjacent sequences for complementarity. Upon successful binding to the target viral DNA, the Cas12a enzyme undergoes a conformational change that activates its collateral cleavage activity [27] [29].

This activated state triggers the trans-cleavage of nearby single-stranded DNA molecules, including reporter probes designed with fluorophore-quencher pairs [26]. The indiscriminate cleavage of these reporters separates the fluorophore from the quencher, generating a measurable fluorescence signal that indicates the presence of the target viral pathogen [26] [27]. This mechanism provides an isothermal amplification strategy that does not require thermal cycling, setting it apart from PCR-based methods and enabling rapid development of point-of-care diagnostic tests for viral pathogens [27] [31].

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR-Cas Systems

The landscape of CRISPR-based diagnostic technologies includes several distinct systems, each with unique characteristics, advantages, and limitations for viral pathogen identification.

Key CRISPR Effector Proteins and Their Properties

Figure 2: Classification of CRISPR Systems for Diagnostics. Different CRISPR systems target specific nucleic acid types and exhibit distinct collateral cleavage activities and PAM requirements, making them suitable for different diagnostic applications.

The selection of CRISPR effector proteins significantly influences assay design, target range, and detection capabilities. Cas12a specializes in DNA targeting with strong collateral cleavage of single-stranded DNA reporters, making it ideal for DNA virus detection [26] [27]. In contrast, Cas13 targets RNA molecules and exhibits collateral cleavage against single-stranded RNA, providing advantages for RNA virus detection without reverse transcription steps [28] [30]. Cas14 shares functional similarities with Cas12a but operates without PAM sequence constraints and demonstrates exceptional single-nucleotide polymorphism discrimination capabilities [28]. Cas9, while revolutionary for gene editing applications, lacks collateral cleavage activity and therefore offers limited utility in diagnostic assays compared to other Cas effectors [26] [28].

Table 1: Comparison of Key CRISPR Effector Proteins for Diagnostic Applications

| Feature | Cas9 | Cas12a | Cas13 | Cas14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | DNA | DNA | RNA | ssDNA |

| PAM Requirement | NGG | TTTV | None | None |

| Collateral Activity | None | ssDNA cleavage | ssRNA cleavage | ssDNA cleavage |

| Sensitivity | Limited for signal amplification | High (aM levels) | High (single molecule) | High |

| Key Applications | Gene editing, limited detection | DNA virus detection, DETECTR | RNA virus detection, SHERLOCK | SNP genotyping, ssDNA pathogens |

| Detection Platforms | CAS-EXPAR | DETECTR, HOLMES | SHERLOCK | DETECTR-Cas14 |

Performance Comparison with Alternative Detection Methods

CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR demonstrates distinct advantages when compared to both traditional molecular detection methods and other CRISPR-based platforms. When evaluated against gold-standard PCR methods, Cas12a systems offer faster turnaround times (often under 1 hour), isothermal operation that eliminates thermal cycling requirements, and comparable sensitivity reaching attomolar (aM) levels for optimized targets [27] [29]. The platform's specificity stems from the dual recognition requirements of both crRNA complementarity and PAM sequence presence, reducing false-positive results compared to amplification-based methods alone [26] [27].

When compared to other CRISPR diagnostics, Cas12a-based DETECTR provides practical advantages over Cas13-based SHERLOCK for DNA virus detection by eliminating the reverse transcription step required for RNA targets [28]. However, for pure RNA virus detection, Cas13 systems may offer more direct targeting without the DNA intermediate conversion. Cas14 demonstrates exceptional single-base resolution but requires additional processing steps to generate single-stranded DNA targets from original samples, adding complexity to workflow implementation [28].

Table 2: Analytical Performance of CRISPR-Cas12a for Viral Pathogen Detection

| Virus Target | Amplification Method | Readout Method | Sensitivity | Detection Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | RPA | Fluorescence | 0.4 copies/μL | 50 min | [27] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | RT-LAMP | Fluorescence (naked eye) | 5 copies/μL | 45 min | [27] |

| African Swine Fever Virus | RPA | Fluorescence/LFD | 6.8 copies/μL | 1 h | [27] |

| MPXV | RPA | Fluorescence/LFA | 1 copy/μL | 45 min | [27] |

| HPV16/18 | RPA | Fluorescence | ~16 aM | 1 h | [27] |

| 12 Respiratory Pathogens | RPA | Fluorescence | 2.5 copies/μL | 90 min | [27] |

Experimental Implementation

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR requires carefully selected research reagents and materials, each serving specific functions within the detection workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas12a Enzyme | Target recognition and cleavage | LbCas12a, AsCas12a, or other orthologs | NEB Lba Cas12a [26] |

| crRNA | Target-specific guidance | 20-44 nt RNA with scaffold and spacer regions | IDT Alt-R CRISPR RNA [26] |

| Reporter Probes | Signal generation | FQ reporters (6-FAM/BHQ1) or FB reporters (FAM/Biotin) | 5'-6-FAM-TTATT-BHQ1-3' [26] |

| Amplification Enzymes | Nucleic acid amplification | RPA, LAMP, or PCR kits | TwistAmp RPA kits [27] [31] |

| Lateral Flow Strips | Visual detection | Test and control lines with capture antibodies | Milenia HybriDetect strips [26] |

| Buffer Systems | Reaction optimization | MgCl₂, DTT, salts for optimal activity | NEBuffer [26] |

Standard DETECTR Workflow and Protocols

The typical CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR protocol follows a structured workflow that can be adapted for various viral targets and detection requirements. The process begins with sample preparation and nucleic acid extraction from clinical specimens, followed by isothermal amplification of target sequences using RPA or LAMP methods [27] [31]. The amplification step typically occurs at 37-42°C for 15-30 minutes, generating sufficient target material for detection without thermal cycling [31].

Following amplification, the CRISPR-Cas12a detection is initiated by combining the amplicon with the Cas12a-crRNA complex and reporter probes. This reaction proceeds at 37°C for 15-30 minutes, during which target recognition triggers collateral cleavage of reporters and signal generation [26] [27]. Finally, result readout occurs through fluorescence measurement (using plate readers or portable devices) or lateral flow detection for visual interpretation [26].

Figure 3: CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR Workflow. The standard implementation involves sample processing, isothermal amplification, CRISPR detection, and multiple options for signal readout depending on available equipment and application requirements.

For two-step detection protocols (amplification and CRISPR reaction in separate tubes), careful optimization is required to prevent amplification inhibitors from affecting the CRISPR detection sensitivity [27] [32]. More advanced one-pot systems physically separate amplification and detection components until activation or utilize engineered crRNA designs that remain inactive until triggered by light or specific enzymes [32]. These integrated approaches reduce contamination risk and simplify operational procedures but may require more extensive optimization to maintain sensitivity with low-copy targets [32].

Advanced Applications and Innovations

RNA Viral Detection Using Cas12a

While Cas12a naturally targets DNA sequences, innovative approaches have been developed to extend its application to RNA virus detection. The SAHARA (Split Activator for Highly Accessible RNA Analysis) system demonstrates that Cas12a can tolerate RNA activators at the PAM-distal region of the crRNA when a short DNA oligonucleotide is provided at the PAM-proximal seed region [33]. This strategy enables reverse transcription-free RNA detection by leveraging the ability of certain Cas12a orthologs to recognize RNA-DNA heteroduplex structures [33].

This RNA detection capability significantly expands the utility of Cas12a-based diagnostics to include major RNA viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, hepatitis C virus, and influenza viruses without requiring the separate Cas13 system [33]. The method achieves picomolar sensitivity for RNA targets and offers improved specificity for point mutation discrimination compared to conventional Cas12a detection, making it valuable for identifying viral variants with single-nucleotide polymorphisms [33].

Multiplexed Detection and Integration

Recent innovations have addressed the challenge of multiplex pathogen detection using Cas12a systems. By employing distinct crRNA arrays with specific PAM-proximal seed DNA requirements, researchers have demonstrated simultaneous detection of multiple viral targets in a single reaction [33]. This multiplexing capability is further enhanced through integration with microfluidic platforms that spatially separate detection reactions or through the use of orthogonal reporter systems with distinct spectral properties [27].

The combination of Cas12a with microfluidic technologies represents a significant advancement toward automated, high-throughput viral testing [27]. These integrated systems compartmentalize reactions, reduce reagent consumption, and enable parallel processing of multiple samples, addressing key scalability challenges for widespread deployment in clinical and public health settings [27]. Additionally, the development of one-pot reactions using engineered circular crRNAs or photochemically controlled systems has simplified operational workflows while maintaining high sensitivity for trace nucleic acid detection in clinical samples [32].

CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR systems represent a versatile and powerful platform for viral pathogen identification, offering an optimal balance of sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation advantages when compared to alternative biosensing technologies. The system's attomolar-level detection sensitivity, rapid turnaround time (often under 1 hour), and flexibility in readout methods (fluorescence, lateral flow, electrochemical) position it as a compelling alternative to both traditional PCR-based methods and other CRISPR-based diagnostics [27] [29].

When specifically compared to Cas9-based systems, Cas12a demonstrates superior utility for diagnostic applications due to its collateral cleavage activity [26] [28]. Against Cas13 platforms, Cas12a offers advantages for DNA virus detection by eliminating reverse transcription requirements, while Cas14 provides enhanced single-nucleotide discrimination but with added workflow complexity [28] [30]. The integration of Cas12a with isothermal amplification methods like RPA and LAMP enables field-deployable testing capabilities without compromising sensitivity [27] [31].

Despite these advantages, challenges remain in optimizing one-pot reactions, standardizing protocols across different viral targets, and facilitating translation from research settings to clinical implementation [27] [32]. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing multiplexing capabilities, improving quantification accuracy, and expanding the detection scope to include non-nucleic acid targets through aptamer-based recognition strategies [27] [34]. As these innovations mature, CRISPR-Cas12a DETECTR systems are poised to become increasingly integral to global efforts in viral pathogen surveillance, outbreak response, and personalized medicine applications.

Electrochemical Biosensors for Point-of-Care and Miniaturized Devices

The field of point-of-care (POC) testing is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by the urgent need for rapid, decentralized, and accessible medical diagnostics. Unlike traditional laboratory-based tests, POC diagnostics aim to provide reliable results at the patient's location, enabling immediate clinical decision-making [35]. Among the various sensing technologies, electrochemical biosensors have emerged as frontrunners in this domain due to their high sensitivity, affordability, compact size, and ease of use [35] [3]. This guide provides a objective comparison of biosensing platforms, with a focused analysis of electrochemical nucleic acid sensors, detailing their operational principles, performance metrics against competing technologies, and the experimental protocols that underpin their functionality. The content is framed within the broader thesis that electrochemical transduction offers a uniquely balanced combination of performance, cost-effectiveness, and miniaturization potential, making it particularly suitable for the next generation of molecular diagnostics at the point of need.

Biosensing Platform Comparison: Optical, Electrochemical, and Magnetic Modalities

Biosensors can be categorized based on their signal transduction mechanism. The following table provides a high-level comparison of the primary modalities used for infectious disease and nucleic acid detection, evaluated against the World Health Organization's ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable) [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Biosensor Modalities for Point-of-Care Nucleic Acid Detection

| Detection Modality | Example Techniques | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical LOD/Performance | Best Suited for POC? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical | Fluorescence, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Very high sensitivity, remote monitoring capability, multiplexing potential [2] [36]. | Instruments can be costly and bulky, susceptible to sample turbidity/interference [2] [36]. | Fluorescence Polarization: 1 CFU for Salmonella in blood [36]. SPR: High sensitivity for antibody-antigen kinetics [2]. | Limited; often requires sophisticated optics and signal processing. |

| Electrochemical | Amperometry, Potentiometry, Impedimetry (EIS) | High sensitivity, portability, low cost, simplicity, low sample volume, robust operation [2] [3] [37]. | Signal can be influenced by temperature; limited shelf-life for some bioreceptors [2]. | Mn-ZIF-67 sensor: 1 CFU mL⁻¹ for E. coli [38]. Nucleic acid sensors: Detection down to fM/ aM concentrations [3] [39]. | Excellent; inherently miniaturizable and compatible with low-cost electronics. |

| Mass-Based | Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) | Label-free detection, very sensitive to mass changes, useful for non-conductive analytes [2]. | Mechanically fragile, thinner quartz for higher sensitivity compromises robustness [2]. | Highly sensitive to mass changes; specific LOD is target-dependent [2]. | Moderate; equipment can be a challenge for true field deployment. |

Experimental Deep Dive: An Electrochemical Nucleic Acid Sensor for Pathogen Detection

To illustrate the practical implementation and performance of electrochemical biosensors, we examine a specific study on a high-performance sensor for detecting Escherichia coli (E. coli) [38].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The following diagram and description outline the key steps in fabricating and operating the Mn-doped ZIF-67 electrochemical biosensor.

Detailed Experimental Methodology [38]:

- Material Synthesis: The Co/Mn Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF-67) was synthesized via a solvothermal method. Precursors of cobalt and manganese salts were combined with the organic ligand 2-methylimidazole in a solvent and heated to form the crystalline, porous bimetallic MOF structure. The Mn doping was systematically varied (Co/Mn ratios of 10:1, 5:1, 2:1, and 1:1) to optimize the structure.

- Electrode Modification: The synthesized Co/Mn ZIF composite was dispersed in a solvent (e.g., ethanol) and drop-casted onto the surface of a working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon electrode). The electrode was then dried to form a stable, modified sensing surface.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Anti-E. coli O-specific antibodies were conjugated to the Co/Mn ZIF-modified electrode surface. This step is critical for ensuring the sensor's specificity. The antibody binds selectively to the O-polysaccharide region of E. coli.

- Electrochemical Measurement: The performance of the biosensor was characterized using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) in a standard redox probe solution like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻. Upon binding of E. coli cells to the antibodies, the electron transfer between the redox probe and the electrode surface is hindered, leading to a measurable change in the electrochemical signal (e.g., an increase in impedance or a decrease in current).

Performance Data and Comparison

The E. coli biosensor demonstrated performance metrics that are highly competitive with other diagnostic platforms, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data for the Mn-ZIF-67 E. coli Biosensor vs. Other Common Methods [38]

| Assay Parameter | Electrochemical Biosensor (Mn-ZIF-67) | Conventional Culture [38] | PCR / RT-qPCR [37] | Optical Fluorescence [36] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | 1 CFU mL⁻¹ | 10-100 CFU mL⁻¹ (after enrichment) | Varies; can be down to a few copies | ~1 CFU for Salmonella [36] |

| Linear Range | 10 to 10¹⁰ CFU mL⁻¹ | Not applicable; qualitative or semi-quantitative | >7-8 log units | Varies by assay |

| Assay Time | ~30 minutes - 1 hour (est.) | 2–10 days [38] | 1–4 hours (including sample prep) [37] | 20 min - 4 hours [36] |

| Specificity | High (discriminated Salmonella, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus) | High | Very High | High |

| Stability | >80% sensitivity over 5 weeks | N/A | Reagents require cold chain | Fluorophores can photobleach |

Key Findings from the Study [38]:

- Mn Doping Enhances Performance: The incorporation of Mn into the ZIF-67 structure induced phase reconstruction, increased the specific surface area (up to 2025 m² g⁻¹ for Co/Mn 1:1), and, most importantly, enhanced electron transfer, which is the cornerstone of the sensor's high sensitivity.

- Mechanism of Detection: The antibody conjugation not only imparts specificity but also modulates the surface wettability. The binding of the bacterial cells selectively blocks electron transfer at the electrode interface, providing a clear and quantifiable signal.

- Real-Sample Applicability: The sensor successfully recovered 93.10–107.52% of E. coli spiked in real tap water samples, demonstrating its robustness and resistance to matrix effects in complex media.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The development and operation of advanced electrochemical biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details key components used in the featured experiment and the broader field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrochemical Nucleic Acid Biosensing

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application in Featured Experiment / General Use |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-67 (ZIF-67) | A cobalt-based metal-organic framework (MOF); provides a highly porous, crystalline structure with a large surface area for biomolecule immobilization and enhanced electrochemical reactions [38]. | Served as the foundational nanomaterial. Its porosity and chemical stability allowed for effective antibody conjugation and interaction with the analyte. |

| Anti-O Antibody | A biorecognition element (immunoglobulin) that specifically binds to the O-polysaccharide antigen on the surface of E. coli bacteria [38] [2]. | Provided the critical specificity for the sensor, enabling selective capture and detection of the target E. coli strain. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probe | A reversible electroactive species, such as Potassium Ferricyanide/K₃[Fe(CN)₆], used to monitor electron transfer efficiency at the electrode interface [38]. | Used in CV and EIS measurements to characterize electrode modification and transduce the bacteria binding event into a measurable signal change. |

| Capture Probe (e.g., ssDNA, Aptamer) | A single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotide (or synthetic analogue like PNA) with a sequence complementary to the target nucleic acid; serves as the biorecognition element for genosensors [3] [39]. | (General Use) Immobilized on the electrode to hybridize with a specific DNA/RNA target from pathogens or cancer biomarkers. |

| Signal Amplification Nanomaterial | Functional nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles, graphene, or enzyme-loaded liposomes used as "nanocarriers" for multiple redox labels [39]. | (General Use) Significantly boosts detection sensitivity by loading thousands of reporter molecules per binding event, enabling attomolar-level detection of nucleic acids [39]. |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows in Nucleic Acid Detection

Electrochemical nucleic acid biosensors operate on the principle of converting a specific hybridization event into a quantifiable electrical signal. The following diagram illustrates the two primary signaling pathways: the "label-free" method and the "nanomaterial-enhanced" method.

Pathway Explanation:

- Label-Free Pathway (Left): The target nucleic acid hybridizes directly with the capture probe immobilized on the electrode. This binding event alters the physical and electrical properties of the electrode-solution interface (e.g., increasing the electrical impedance by blocking the approach of the redox probe). Techniques like EIS are ideally suited to detect this change, allowing for quantification without the need for additional labels [35] [3].

- Nanomaterial-Enhanced Pathway (Right): For ultra-sensitive detection, a signal amplification strategy is employed. This often involves a reporter probe, complementary to another region of the target, which is conjugated to a nanomaterial (e.g., a gold nanoparticle). This nanomaterial can be pre-loaded with a vast number of redox reporter molecules (e.g., methylene blue) or possess catalytic properties. Upon hybridization, each binding event introduces thousands of reporters to the electrode surface, resulting in a dramatically amplified current signal when measured by techniques like SWV or DPV [3] [39]. This pathway is key to achieving detection limits that rival or surpass those of PCR-based methods, without the need for target amplification.

Electrochemical biosensors, particularly those leveraging nucleic acid recognition and nanomaterial-enhanced signal amplification, represent a powerful and competitive technology for point-of-care molecular diagnostics. As demonstrated by the comparative data and the deep dive into a specific pathogen sensor, this platform successfully balances high analytical performance—rivaling optical methods in sensitivity and specificity—with the practical advantages of portability, low cost, and rapid analysis time that are essential for decentralized testing [35] [38] [3]. The ongoing integration of these sensors with microfluidic systems, the development of novel bioreceptors like aptamers, and the convergence with IoT and AI for data handling are poised to further revolutionize healthcare management, moving sophisticated diagnostic capabilities from centralized laboratories directly into the hands of clinicians and patients [3] [40].

Functional nucleic acids (FNAs), primarily aptamers and DNAzymes, have emerged as powerful molecular recognition elements in biosensing, offering a compelling alternative to traditional protein-based reagents like antibodies. Their unique properties—including high stability, synthetic accessibility, and structural versatility—are driving innovation in diagnostic applications, from point-of-care testing to environmental monitoring [41] [42]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and practical implementation of aptamer and DNAzyme-based biosensing platforms, contextualized within the broader field of nucleic acid detection research.

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind specific targets with high affinity and selectivity, while DNAzymes are catalytic DNA molecules capable of accelerating chemical reactions [41]. Both are isolated through in vitro selection processes and integrated into biosensors to detect targets ranging from metal ions and small molecules to proteins, whole cells, and pathogens [41] [43]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative advantages, limitations, and appropriate use cases for these FNAs is critical for designing next-generation detection systems.

Fundamental Properties and Comparative Analysis

Structural and Functional Characteristics