Next-Generation Sequencing for DNA and RNA Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies and their transformative impact on genomic research and drug development.

Next-Generation Sequencing for DNA and RNA Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies and their transformative impact on genomic research and drug development. It covers foundational principles, from first-generation Sanger sequencing to current short- and long-read platforms like Illumina, PacBio, and Nanopore. The scope extends to methodological applications in oncology, rare diseases, and infectious diseases, alongside detailed protocols for library preparation, data analysis, and bioinformatics. The content also addresses critical troubleshooting, optimization strategies for common challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks required for clinical implementation. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current trends, practical applications, and future directions to empower the effective use of NGS in advancing precision medicine.

The NGS Revolution: From Sanger Sequencing to Modern Genomics

The ability to decipher the genetic code has fundamentally transformed biological research and clinical diagnostics. The evolution of DNA sequencing technology, from its inception to the modern era, represents a journey of remarkable scientific innovation, characterized by exponential increases in speed and throughput and precipitous drops in cost [1] [2]. These advances have propelled diverse fields, from personalized medicine to drug discovery, by providing an unparalleled view into the blueprints of life [3] [4]. This article traces the development of sequencing technologies through three distinct generations, providing a structured comparison of their characteristics and detailing foundational protocols that underpin contemporary next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows for DNA and RNA analysis.

The Generations of Sequencing Technology

First-Generation Sequencing: The Foundations

The first major breakthrough in DNA sequencing occurred in 1977 with the introduction of two methods: the chemical degradation method by Alan Maxam and Walter Gilbert and the chain-termination method by Frederick Sanger and colleagues [1] [5]. The Maxam-Gilbert method used chemicals to cleave DNA at specific bases (A, G, C, or T/C), followed by separation of the resulting fragments via gel electrophoresis and detection by autoradiography [1] [2]. While groundbreaking, this method was technically challenging and used hazardous chemicals.

The Sanger method, which became the dominant first-generation technology, uses a different approach. It relies on the random incorporation of dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs) during in vitro DNA replication [1]. These ddNTPs lack a 3'-hydroxyl group, which prevents the formation of a phosphodiester bond with the next incoming nucleotide, thereby terminating DNA strand elongation [1]. In its original form, four separate reactions—each containing one of the four ddNTPs—were run. The resulting fragments of varying lengths were separated by gel electrophoresis, and the sequence was determined based on their migration [5].

A critical advancement came with the automation of Sanger sequencing. The development of fluorescently labeled ddNTPs and the replacement of slab gels with capillary electrophoresis enabled the creation of automated DNA sequencers [1] [2]. The first commercial automated sequencer, the ABI 370 from Applied Biosystems, significantly increased throughput and accuracy and became the primary workhorse for the landmark Human Genome Project [1] [5]. Despite its accuracy, automated Sanger sequencing remained relatively low-throughput and expensive for sequencing large genomes, highlighting the need for new technologies [2].

Second-Generation Sequencing: The High-Throughput Revolution

Second-generation sequencing, or next-generation sequencing (NGS), is defined by its ability to perform massively parallel sequencing, enabling the simultaneous analysis of millions to billions of DNA fragments [6] [4]. This paradigm shift dramatically reduced the cost and time required for sequencing, making large-scale projects like whole-genome sequencing accessible to individual labs [4].

A key differentiator of most second-generation platforms is their reliance on a template amplification step prior to sequencing. Three primary amplification methods are used:

- Emulsion PCR: Used by 454 pyrosequencing and Ion Torrent platforms, where DNA fragments are amplified on beads in water-in-oil emulsions [6].

- Bridge Amplification: Used by Illumina platforms, where DNA fragments are amplified on a solid surface (a flow cell) to form clonal clusters [6] [2].

- DNA Nanoball Generation: Used by BGI/MGI, where rolling circle amplification creates DNA nanoballs that are deposited on a patterned flow cell [6] [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Second-Generation Sequencing Platforms

| Platform (Company) | Sequencing Chemistry | Amplification Method | Key Principle | Typical Read Length | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 454 GS FLX (Roche) [7] [2] | Pyrosequencing | Emulsion PCR | Detection of pyrophosphate (PPi) release, converted to light via luciferase | 400-1000 bp | Difficulty with homopolymer regions, leading to insertion/deletion errors |

| Ion Torrent (Thermo Fisher) [7] | Sequencing by Synthesis | Emulsion PCR | Semiconductor detection of hydrogen ions (H+) released upon nucleotide incorporation | 200-400 bp | Signal degradation in homopolymer regions affects accuracy |

| Illumina (e.g., MiSeq, NovaSeq) [6] [7] [4] | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) | Bridge PCR | Fluorescently-labeled, reversible terminator nucleotides; imaging after each base incorporation | 36-300 bp | Signal decay and dephasing over many cycles can lead to errors |

| SOLiD (Applied Biosystems) [7] | Sequencing by Ligation | Emulsion PCR | Ligation of fluorescently-labeled di-base probes | 75 bp | Short reads and complex data analysis |

The massive data output of these platforms necessitated parallel advances in bioinformatics for data assembly, alignment, and variant calling [7]. While second-generation sequencing provides high accuracy and low cost per base, its primary limitation is short read length, which complicates the assembly of complex genomic regions and the detection of large structural variations [6].

Third-Generation Sequencing: The Long-Read Era

Third-generation sequencing technologies emerged to address the limitations of short reads. Their defining characteristic is the ability to sequence single DNA molecules in real time, without the need for a prior amplification step, producing long reads that can span thousands to tens of thousands of bases [8] [9]. This is particularly valuable for de novo genome assembly, resolving repetitive regions, identifying large structural variants, and detecting epigenetic modifications directly [6] [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Third-Generation Sequencing Platforms

| Platform (Company) | Sequencing Chemistry | Template Preparation | Key Principle | Typical Read Length | Accuracy & Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio SMRT Sequencing [6] [8] [9] | Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) | SMRTbell library (circulared DNA) | Real-time detection of fluorescent nucleotide incorporation by polymerase immobilized in a zero-mode waveguide (ZMW) | >15,000 bp (average) | HiFi Reads: >99.9% accuracy via circular consensus sequencing (CCS) [6] [8] |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) [6] [7] [8] | Nanopore Sequencing | Ligation of adapters to native DNA | Measurement of changes in ionic current as DNA strand passes through a protein nanopore | 10,000-30,000 bp (average) | ~99% raw accuracy (Q20) with latest kits; real-time, portable sequencing (MinION) [8] |

Initially, third-generation technologies were characterized by higher per-base error rates compared to second-generation platforms. However, continuous improvements have substantially increased their accuracy. PacBio's HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads achieve high accuracy by repeatedly sequencing the same circularized DNA molecule to generate a consensus sequence [8]. Oxford Nanopore's accuracy has been improved through updated chemistries (e.g., Kit 14) and advanced base-calling algorithms like Dorado, with duplex reads now exceeding Q30 (>99.9% accuracy) [8] [9].

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Illumina NGS Workflow for Whole Transcriptome RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq)

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for preparing RNA-Seq libraries for sequencing on Illumina's short-read platforms, a cornerstone of gene expression analysis [4].

Principle

RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) utilizes NGS to determine the sequence and abundance of RNA molecules in a biological sample. It allows for the discovery of novel transcripts, quantification of gene expression levels, and analysis of alternative splicing events [4].

Reagents and Equipment

- Total RNA or mRNA sample (high quality, RIN > 8)

- Oligo(dT) magnetic beads or rRNA depletion kits for enrichment

- Fragmentation buffer

- Reverse Transcriptase and random hexamer/oligo(dT) primers

- DNA Polymerase I, RNase H, and dNTPs

- NGS Library Preparation Kit (e.g., Illumina TruSeq)

- SPRIselect beads or other solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads for cleanup

- Indexing Adapters (Illumina) for sample multiplexing

- Quantification instruments (Qubit, Bioanalyzer/Tapestation)

- Illumina Sequencing Platform (e.g., MiSeq, NovaSeq)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Isolate total RNA from your sample (e.g., cells or tissue) using a validated method. Assess RNA integrity and concentration using an instrument like the Agilent Bioanalyzer.

- RNA Enrichment:

- For mRNA Sequencing: Use oligo(dT) magnetic beads to selectively enrich for poly-adenylated mRNA.

- For Total RNA Sequencing: Use commercial kits to deplete abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

- RNA Fragmentation and Priming: Fragment the purified RNA using divalent cations at elevated temperature (e.g., Mg²⁺ at 94°C for several minutes) to generate fragments of a desired size (e.g., 200-300 nucleotides). Prime the fragmented RNA using random hexamer primers.

- First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) using Reverse Transcriptase and dNTPs. This creates an RNA-DNA hybrid.

- Second-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Remove the RNA template using RNase H and synthesize the second cDNA strand using DNA Polymerase I and dNTPs, resulting in double-stranded cDNA (ds-cDNA).

- Library End-Repair and A-Tailing: The ds-cDNA fragments are blunt-ended, and a single 'A' nucleotide is added to the 3' ends to facilitate ligation with the indexing adapters, which have a complementary 'T' overhang.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate the unique dual-indexed adapters provided in the kit to the A-tailed cDNA fragments. These adapters contain the sequences required for binding to the Illumina flow cell and for priming the sequencing reactions.

- Library Amplification and Cleanup: Perform a limited-cycle PCR (e.g., 10-15 cycles) to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments and amplify the library. Purify the final library using SPRI beads to remove excess primers and adapter dimers.

- Library Quality Control and Quantification: Validate the library's size distribution using the Bioanalyzer and accurately quantify the concentration using a fluorescence-based method (Qubit).

- Pooling and Sequencing: Normalize and pool multiple, uniquely indexed libraries into a single tube for multiplexed sequencing. Load the pool onto the Illumina flow cell for cluster generation and sequencing-by-synthesis.

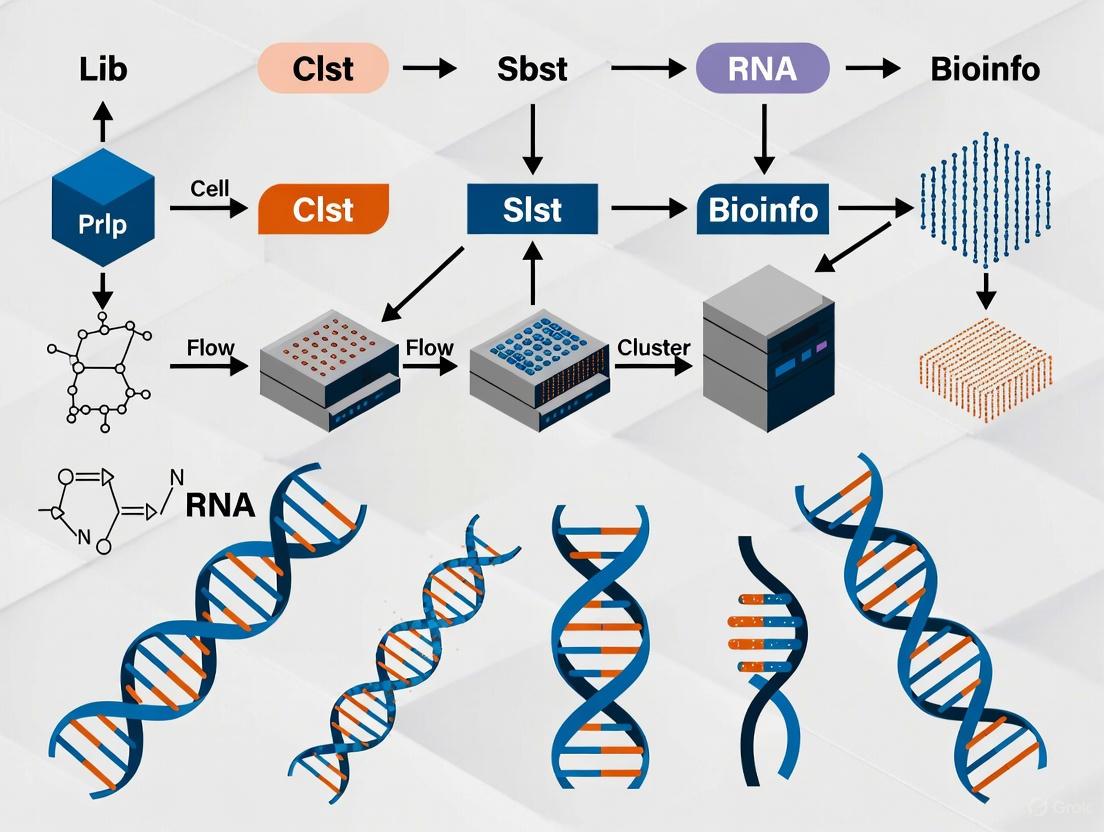

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

Diagram: RNA-Seq Library Preparation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Their Functions in NGS Workflows

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in NGS Workflow | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic SPRI Beads [4] | Size-selective cleanup and purification of DNA fragments at various steps (post-fragmentation, post-ligation, post-PCR). | Solid-phase reversible immobilization; allow for buffer-based size selection and removal of enzymes, salts, and short fragments. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes/Buffers [4] | Controlled digestion of DNA or RNA into fragments of optimal size for sequencing. | Enable reproducible and tunable fragmentation (e.g., via acoustic shearing or enzymatic digestion). |

| Indexing Adapters [4] | Unique oligonucleotide sequences ligated to DNA fragments to allow multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing run. | Contain flow cell binding sequences, priming sites, and a unique dual index for sample identification post-sequencing. |

| Polymerases for Library Amplification [4] | High-fidelity PCR amplification of the adapter-ligated library to generate sufficient material for sequencing. | Exhibit high processivity and fidelity to minimize amplification biases and errors. |

| Flow Cells [6] [4] | The solid surface where clonal clusters are generated and the sequencing reaction occurs. | Coated with oligonucleotides complementary to the adapters; patterned flow cells (Illumina) increase density and data output. |

| SBS Chemistries (e.g., XLEAP-SBS) [4] | The chemical cocktail of fluorescently-labeled, reversible terminator nucleotides and enzymes used for sequencing-by-synthesis. | Determine the speed, accuracy, and read length of the sequencing run. |

The evolution from first- to third-generation sequencing technologies has been nothing short of revolutionary, each generation building upon the limitations of the last. The field continues to advance rapidly, with emerging trends focusing on multi-omic integration, spatial transcriptomics, and even higher throughput at lower costs [6] [8]. As these technologies mature and become more integrated into research and clinical pipelines, they promise to further deepen our understanding of genome biology and accelerate the development of novel diagnostics and therapeutics in the era of precision medicine.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a transformative technology that enables the ultra-high-throughput, parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously [10] [4]. This approach has revolutionized genomics by making large-scale sequencing dramatically faster and more cost-effective than traditional methods, facilitating a wide range of applications from basic research to clinical diagnostics [7].

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Core Principles

- NGS Workflow and Technologies

- Applications and Experimental Protocols

- The Scientist's Toolkit

The core principles of NGS represent a fundamental shift from first-generation sequencing. The key differentiator is massively parallel sequencing, which allows for the concurrent reading of billions of DNA fragments, as opposed to the one-fragment-at-a-time approach of Sanger sequencing [10]. This parallelism directly enables the other two principles: high-throughput data generation and significant cost-effectiveness.

The impact of these principles is profound. The Human Genome Project, which relied on Sanger sequencing, took 13 years and cost nearly $3 billion [10] [4]. In stark contrast, modern NGS platforms can sequence an entire human genome in hours for under $1,000 [10]. This democratization of sequencing has opened up possibilities for population-scale studies and routine clinical application.

Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Generations

Table 1: Key characteristics of different sequencing generations.

| Feature | First-Generation (Sanger) | Second-Generation (NGS) | Third-Generation (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Chain-termination | Massively parallel sequencing by synthesis or ligation [4] [7] | Real-time, single-molecule sequencing [10] [7] |

| Throughput | Low (single fragment per run) | Very High (millions to billions of fragments per run) [4] | High (hundreds of thousands of long fragments) |

| Read Length | Long (500-1000 base pairs) [10] | Short (50-600 base pairs, typically) [10] | Very Long (10,000 - 30,000+ base pairs on average) [7] |

| Cost per Genome | ~$3 billion [10] | <$1,000 [10] | Higher than NGS |

| Primary Applications | Targeted sequencing, validation | Whole-genome sequencing, transcriptomics, targeted panels [4] | De novo genome assembly, resolving complex regions, epigenetic modification detection [10] |

NGS Workflow and Technologies

The standard NGS workflow is a multi-stage process that converts a purified nucleic acid sample into actionable digital sequence data. The following diagram illustrates the primary workflow and the underlying technology that enables parallel sequencing.

NGS Workflow and Sequencing Principle

Detailed Workflow Breakdown

Library Preparation

The process begins with library preparation, where input DNA or RNA is fragmented into appropriate sizes, and platform-specific adapter sequences are ligated to the ends of these fragments [10]. These adapters are essential for the subsequent steps of amplification and sequencing.

Protocol: Standard DNA Library Prep (Illumina)

- Input: 100-1000 ng of high-quality genomic DNA.

- Fragmentation: Use a Covaris sonicator or enzymatic fragmentation (e.g., Nextera tagmentation) to shear DNA to a target size of 200-500 bp.

- End-Repair & A-Tailing: Convert fragmented DNA into blunt-ended, 5'-phosphorylated fragments, then add a single 'A' nucleotide to the 3' ends.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate indexed adapters containing the 'T' overhang to the 'A'-tailed fragments using T4 DNA ligase. Purify the ligated product with SPRI beads.

- Library QC: Validate the final library size distribution using an Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation and quantify using qPCR.

Cluster Amplification

In this step, the adapter-ligated library is loaded onto a flow cell, a glass surface containing immobilized oligonucleotides complementary to the adapters. Each DNA fragment binds to the flow cell and is amplified locally in a process called bridge amplification, generating millions of clonal clusters [10]. Each cluster ultimately produces a strong enough signal to be detected by the sequencer's camera.

Parallel Sequencing

Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) is the most common chemistry (used by Illumina). The flow cell is cyclically flooded with fluorescently tagged nucleotides. As each nucleotide is incorporated into the growing DNA chain by a polymerase, its fluorescent dye is imaged, revealing the sequence of each cluster. This process happens for hundreds of millions of clusters in parallel, creating an enormous throughput [4]. Recent advancements like XLEAP-SBS chemistry have further increased the speed and fidelity of this process [4].

Comparison of NGS Platform Technologies

Table 2: Overview of major short- and long-read NGS platform technologies.

| Platform | Technology | Amplification Method | Read Length | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing by Synthesis | Bridge PCR [7] | 36-300 bp [7] | Short reads complicate assembly of repetitive regions [10] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor (H+ detection) | Emulsion PCR [7] | 200-400 bp [7] | Signal degradation in homopolymer regions [7] |

| PacBio SMRT | Real-time sequencing (fluorescence) | None (Single Molecule) [7] | Average 10,000-25,000 bp [7] | Higher cost per run compared to short-read platforms [7] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Electrical signal detection (Nanopore) | None (Single Molecule) [7] | Average 10,000-30,000 bp [7] | Raw read error rate can be higher than other technologies [7] |

Applications and Experimental Protocols

The principles of NGS enable its application across diverse fields. The following diagram outlines the primary clinical and research applications.

Primary NGS Application Areas

Protocol: Somatic Variant Detection in Cancer

This protocol identifies tumor-specific mutations for therapy selection and resistance monitoring [11].

- Objective: To detect somatic single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number variations (CNVs) from matched tumor-normal sample pairs.

- Sample Requirements: 50-100 ng of DNA from both FFPE tumor tissue and matched normal (e.g., blood or saliva). Input can be lowered to 10 ng using specialized library prep kits.

- Library Preparation: Use a hybrid-capture-based targeted panel (e.g., a comprehensive cancer gene panel) or perform whole-exome sequencing. Follow manufacturer's protocol for end-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification.

- Sequencing: Sequence on an Illumina platform to a minimum depth of 250x for tumor and 100x for normal samples for WES; deeper coverage (500-1000x) is required for targeted panels to detect low-frequency variants.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess read quality. Trim adapters and low-quality bases with Trimmomatic [11].

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using a short-read aligner like BWA-MEM [11].

- Variant Calling: Use MuTect2 for SNVs/indels and Control-FREEC or GATK for CNVs. Filter variants against population databases (e.g., gnomAD, dbSNP) to remove common polymorphisms.

- Annotation & Reporting: Annotate variants with ANNOVAR or SnpEff [11]. Interpret clinically actionable variants using resources like CIViC, OncoKB, and COSMIC [11].

Protocol: Liquid Biopsy for Therapy Monitoring

Liquid biopsies analyze circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood plasma, offering a non-invasive method to track tumor dynamics [10].

- Objective: To quantify allele frequency of known tumor mutations in plasma ctDNA for monitoring treatment response and emergent resistance.

- Sample Collection & Processing: Collect 10 mL of blood in cell-free DNA collection tubes (e.g., Streck). Process within 6 hours: double centrifugation (1600xg then 16,000xg) to isolate plasma. Extract cell-free DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit).

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Prepare libraries from 10-50 ng of cell-free DNA. Use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for PCR amplification errors and sequencing artifacts. Sequence with a targeted panel covering known resistance mutations to very high depth (>10,000x).

- Data Analysis:

- Process data through a standard alignment and variant calling pipeline (as above).

- Use UMI-based error suppression tools (e.g., fgbio) to distinguish true low-frequency variants from technical noise.

- Track the variant allele fraction (VAF) of key mutations over time. A decreasing VAF indicates treatment response, while an emerging or increasing VAF suggests resistance.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful NGS experimentation relies on a suite of specialized reagents, instruments, and computational tools.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for NGS workflows.

| Item | Function | Example Kits/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares DNA/RNA fragments for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters [10]. | Illumina Nextera, NEBNext Ultra II |

| Hybrid-Capture Probes | Biotinylated oligonucleotides used to enrich for specific genomic regions of interest in targeted sequencing [11]. | IDT xGen Lockdown Probes, Twist Core Exome |

| Cluster Generation Reagents | Enzymes and nucleotides for the bridge amplification on the flow cell, creating clonal clusters for sequencing [10]. | Illumina Exclusion Amplification reagents |

| SBS Chemistry Kit | Fluorescently labeled nucleotides and enzymes for the cyclic sequencing-by-synthesis reaction during the run [4]. | Illumina XLEAP-SBS Chemistry |

| Quality Control Kits | For assessing the quality, quantity, and fragment size of input DNA and final libraries pre-sequencing. | Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA High Sensitivity Kit, Qubit dsDNA HS Assay |

Essential Bioinformatics Tools and Databases

The massive data output of NGS requires robust bioinformatics pipelines for analysis and interpretation [11].

- Primary Analysis Tools:

- Key Databases for Interpretation:

- dbSNP: Catalog of common human genetic variations [11].

- COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer): Curated database of somatic mutations in cancer [11].

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): Repository of cancer genomic and clinical data [11].

- Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD): Population database of genetic variation used for filtering common variants [11].

- Cloud Computing Platforms: To handle the computational and data storage demands, cloud-based solutions like Illumina Connected Analytics and DRAGEN pipelines are widely used [11] [4].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized genomic research by enabling the high-throughput analysis of DNA and RNA. This section details the core principles and comparative specifications of the three major platforms: Illumina, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT).

Illumina utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry. This technology employs fluorescently labeled nucleotides that serve as reversible terminators. During each cycle, a single nucleotide is incorporated, its fluorescence is imaged for base identification, and the terminator is cleaved to allow the next cycle. This process generates massive volumes of short reads (typically 50-300 bp) with high per-base accuracy, often exceeding Q30 (99.9%) [4].

PacBio Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing is based on the real-time observation of DNA synthesis. A single DNA polymerase molecule is anchored to the bottom of a zero-mode waveguide (ZMW). As nucleotides are incorporated, each base-specific fluorescent label is briefly illuminated and detected. The key feature is the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) mode, where a single DNA molecule is sequenced repeatedly in a loop. This produces HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads that combine long read lengths (typically 10-25 kb) with very high accuracy (exceeding 99.9%) [12] [13].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing is based on the translocation of nucleic acids through protein nanopores. As DNA or RNA passes through a nanopore embedded in an electrically resistant membrane, it causes characteristic disruptions in an ionic current. These current changes are decoded in real-time to determine the nucleotide sequence. A primary advantage of this technology is its ability to sequence long fragments (from 50 bp to over 4 Mb) directly from native DNA/RNA, thereby preserving base modification information like methylation as a standard feature [14] [15].

Table 1: Comparative Specifications of Major NGS Platforms

| Feature | Illumina | PacBio (SMRT Sequencing) | Oxford Nanopore (ONT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) [4] | Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) in Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs) [13] | Nanopore-based current sensing [15] |

| Read Length | Short reads (up to 300 bp, paired-end) [4] | Long reads (average 10-25 kb) [13] | Ultra-long reads (50 bp to >4 Mb) [15] |

| Typical Accuracy | >Q30 (99.9%) [4] | >Q27 (99.9%) for HiFi reads [12] | ~Q20 (99%) with latest chemistries [12] |

| Primary Strengths | High throughput, low per-base cost, well-established workflows [4] | High accuracy long reads, direct methylation detection [16] [13] | Ultra-long reads, real-time analysis, portability [14] [15] |

| Key Limitations | Short reads limit resolution in complex regions, amplification bias [15] | Lower throughput per instrument compared to Illumina, higher DNA input requirements [13] | Higher raw error rate than competitors, though improving [17] |

| Methylation Detection | Requires specialized prep (bisulfite sequencing) [18] | Built-in (kinetics-based) for 6mA and more [13] | Built-in (signal-based) for 5mC, 6mA, and more [14] |

Performance Comparison in Microbial Community Profiling

Amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene is a foundational method for profiling microbial communities. The choice of sequencing platform significantly impacts taxonomic resolution and perceived community composition, as demonstrated by recent comparative studies.

A 2025 study on rabbit gut microbiota directly compared Illumina (V3-V4 region), PacBio (full-length 16S), and ONT (full-length 16S). The results highlighted a clear advantage for long-read platforms in species-level resolution. ONT classified 76% of sequences to the species level, PacBio classified 63%, while Illumina classified only 48%. However, a critical limitation was noted across all platforms: a majority of sequences classified at the species level were assigned ambiguous names like "uncultured_bacterium," indicating persistent gaps in reference databases rather than a failure of the technology itself [12].

Furthermore, the same study found significant differences in beta diversity analysis, showing that the taxonomic compositions derived from the three platforms were not directly interchangeable. This underscores that the sequencing platform and the choice of primers are significant variables in experimental design [12]. A separate 2025 study on soil microbiomes concluded that PacBio and ONT provided comparable assessments of bacterial diversity, with PacBio showing a slight edge in detecting low-abundance taxa. Importantly, despite ONT's inherent higher error rate, its results closely matched PacBio's for well-represented taxa, suggesting that the errors do not critically impact the broader interpretation of community structure [19].

Table 2: 16S rRNA Sequencing Performance Across Platforms

| Metric | Illumina (V3-V4) | PacBio (Full-Length) | ONT (Full-Length) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species-Level Classification Rate | 48% [12] | 63% [12] | 76% [12] |

| Genus-Level Classification Rate | 80% [12] | 85% [12] | 91% [12] |

| Representative Read Length | 442 bp [12] | 1,453 bp [12] | 1,412 bp [12] |

| Impact on Beta Diversity | Significant differences observed compared to long-read platforms [12] | Significant differences observed compared to other platforms [12] | Significant differences observed compared to other platforms [12] |

| Reported Community Richness | Higher (in respiratory microbiome study) [17] | Comparable to ONT in soil study [19] | Slightly lower than Illumina in respiratory study [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Full-Length 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

The following protocol details a standardized workflow for full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing, adapted for both PacBio and Oxford Nanopore platforms, based on recently published methods [12] [19].

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: For gut microbiota studies, collect soft feces or intestinal content samples and immediately freeze them at -72°C until DNA extraction [12]. For soil microbiomes, homogenize soil samples and pass through a 1 mm sieve under sterile conditions before storage [19].

- DNA Extraction: Isolate bacterial genomic DNA using a dedicated kit, such as the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) or the Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit (Zymo Research), following the manufacturer's protocol [12] [19].

- Quality Control: Quantify the extracted DNA using a fluorescence-based method (e.g., Qubit Fluorometer). Assess DNA quality and integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis or a Fragment Analyzer [19].

PCR Amplification and Library Preparation

The steps diverge based on the target platform.

A. PacBio HiFi Library Preparation

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the full-length 16S rRNA gene using universal primers 27F and 1492R, tailed with PacBio barcode sequences. Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., KAPA HiFi HotStart) and run the reaction for 27-30 cycles [12] [19].

- Amplicon Pooling: Verify the PCR product size and quantity using a Fragment Analyzer. Pool amplicons from different samples in equimolar concentrations.

- SMRTbell Library Construction: Prepare the library from the pooled amplicons using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 or 3.0. This creates a circular DNA template suitable for SMRT sequencing [12] [19].

- Sequencing: Sequence the library on a PacBio Sequel II or Revio system using a sequencing kit such as the Sequel II Sequencing Kit 2.0, typically with a 10-hour movie time [12] [19].

B. Oxford Nanopore Library Preparation

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the full-length 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9 regions) using the primers from the 16S Barcoding Kit (e.g., SQK-16S024). Perform PCR amplification for 40 cycles [12].

- Amplicon Purification and Pooling: Purify the PCR product using magnetic beads (e.g., KAPA HyperPure Beads). Quantify the purified amplicons and pool them in equimolar amounts [19].

- Sequencing: Load the pooled library onto a MinION flow cell (e.g., R10.4.1) and sequence on a MinION device. Sequencing can be run for a predetermined time (e.g., 24-72 hours) or until the flow cell is exhausted [12] [17].

Bioinformatic Analysis

- PacBio Data Processing: Process the raw subreads to generate Circular Consensus Sequences (CCS) reads, which are high-fidelity HiFi reads. Demultiplex the reads by sample barcodes. Use the DADA2 pipeline in QIIME2 for denoising, error-correction, and generation of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [12].

- ONT Data Processing: Basecall and demultiplex raw FAST5 files using Dorado with a high-accuracy (HAC) model. Due to the higher error profile, ONT reads are often processed using specialized pipelines like Spaghetti or the EPI2ME 16S Workflow, which employ an Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) clustering approach for denoising [12] [17].

- Taxonomic Assignment: For both platforms, import high-quality sequences into QIIME2. A Naïve Bayes classifier, trained on a reference database (e.g., SILVA) and customized for the specific primers and read length, is typically used for taxonomic annotation from phylum to species level [12].

- Downstream Analysis: Perform diversity analysis (alpha and beta diversity) using tools like phyloseq in R. Filter out sequences classified as Archaea, Eukaryota, or unassigned, and remove low-abundance ASVs/OTUs (e.g., those with a relative abundance below 0.01%) to minimize artifacts [12].

Diagram 1: Full-length 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing workflow for PacBio and ONT platforms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for NGS Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality, inhibitor-free genomic DNA from complex samples. | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) [12], Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit (Zymo Research) [19] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of the target 16S rRNA gene with low error rates during PCR. | KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA Polymerase [12] |

| Full-Length 16S Primers | Amplification of the ~1,500 bp full-length 16S rRNA gene. | Universal primers 27F / 1492R [12] [19] |

| Multiplexing Barcodes | Sample-specific nucleotide tags allowing pooled sequencing of multiple libraries. | PacBio Barcoded Primers [12], ONT Native Barcoding Kit 96 [19] |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit | Construction of SMRTbell libraries for PacBio circular consensus sequencing. | SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0/3.0 [12] [19] |

| ONT 16S Barcoding Kit | An all-in-one kit for amplification, barcoding, and library prep for Nanopore 16S sequencing. | SQK-16S024 [12] |

| Sequencing Kit & Flow Cell | Platform-specific reagents and consumables for the sequencing run. | Sequel II Sequencing Kit 2.0, SMRT Cell [12], MinION Flow Cell (R10.4.1) [17] |

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research and clinical diagnostics by enabling high-throughput, cost-effective analysis of DNA and RNA. This guide details the experimental protocols and key applications of four major sequencing methodologies.

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Whole Genome Sequencing provides a comprehensive view of an organism's complete genetic code, enabling the discovery of variants across coding, non-coding, and structural regions.

WGS identifies single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels), structural variations (SVs), and copy number variations (CNVs) across the entire genome. The UK Biobank project demonstrated its power by sequencing 490,640 participants, identifying approximately 1.5 billion genetic variants—42 times more than what was detectable through whole-exome sequencing [20]. This comprehensive approach is invaluable for population genetics, rare disease research, and characterizing the non-coding genome.

Experimental Protocol: Illumina Short-Read WGS

Library Preparation

- DNA Extraction: Obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA from source material (e.g., blood, tissue, cells) using systems like Autopure LS (Qiagen) or GENE PREP STAR NA-480 (Kurabo). Assess DNA quality and quantity with fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit) [21].

- Fragmentation: Fragment genomic DNA to an average target size of 550 bp using a focused-ultrasonicator (e.g., Covaris LE220) [21].

- Library Construction: Use a PCR-free library prep kit (e.g., TruSeq DNA PCR-free HT for Illumina or MGIEasy PCR-Free DNA Library Prep Set for MGI platforms) to prevent amplification bias. Ligate platform-specific adapters, which often include unique dual indexes for multiplexing [21].

- Automation: Employ automated liquid handling systems (e.g., Agilent Bravo, Biomek NXp, or MGI SP-960) for high-throughput, reproducible library preparation [21].

Sequencing & Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Load libraries onto a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq X Plus, NovaSeq 6000, or DNBSEQ-T7). Sequence to a minimum coverage of 30x for human genomes; the UK Biobank achieved an average coverage of 32.5x [20].

- Primary Analysis: Convert raw signal data (e.g., base calls) into FASTQ files containing sequence reads and quality scores.

- Secondary Analysis:

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using aligners like BWA or BWA-mem2 [21].

- Variant Calling: Identify SNPs and indels using GATK HaplotypeCaller. Perform joint genotyping across multiple samples with GATK GnarlyGenotyper, followed by variant quality score recalibration (VQSR) [21].

- SV Calling: Detect larger structural variants (>50 bp) using specialized callers like DRAGEN SV [20].

WGS Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Products/Kits |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Iserts high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA for accurate long-range analysis. | Autopure LS (Qiagen), GENE PREP STAR NA-480 (Kurabo) [21] |

| DNA Quantitation Kit | Precisely measures DNA concentration using fluorescent dye binding, critical for optimal library preparation. | Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen) [21] |

| PCR-free Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries without PCR amplification to prevent associated biases and errors. | TruSeq DNA PCR-free HT (Illumina), MGIEasy PCR-Free Set (MGI) [21] |

| Unique Dual Indexes | Allows multiplexing of numerous samples by tagging each with unique barcodes, enabling sample pooling and post-sequencing demultiplexing. | IDT for Illumina TruSeq DNA UD Indexes [21] |

| Sequencing Reagent Kit | Provides enzymes, buffers, and nucleotides required for the sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry on the platform. | NovaSeq X Plus 10B/25B Reagent Kit (Illumina) [21] |

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)

Whole Exome Sequencing targets the protein-coding regions of the genome (the exome), which constitutes about 1-2% of the genome but harbors the majority of known disease-causing variants.

WES provides a cost-effective method for identifying variants in exonic regions, making it highly efficient for diagnosing rare Mendelian disorders and other conditions linked to coding sequences. It is considered medically necessary for specific clinical presentations, such as multiple anomalies not suggestive of a specific condition, developmental delay, or congenital epilepsy of unknown cause [22].

WES vs. WGS Quantitative Comparison

| Parameter | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | ~1.5% of genome (exonic regions) [22] | 100% of genome [20] |

| Typical Coverage | 100x - 150x | 30x - 40x |

| Variant Discovery (in UK Biobank) | ~25 million variants [20] | ~1.5 billion variants (60x more) [20] |

| 5' and 3' UTR Variant Capture | Low (e.g., ~10-30% of variants) [20] | ~99% of variants [20] |

| Primary Clinical Use | Diagnosis of rare genetic disorders, idiopathic developmental delay [22] | Comprehensive variant discovery, non-coding region analysis, structural variation [20] |

Experimental Protocol: Illumina Short-Read WES

Library Preparation & Target Enrichment

- Library Construction: Follow a similar initial protocol as WGS: fragment DNA and ligate sequencing adapters.

- Target Capture: The critical differentiating step for WES. Hybridize the library to biotinylated probes (e.g., Illumina Exome Panel, IDT xGen Exome Research Panel) that are complementary to the exonic regions. These probes "pull down" the target fragments.

- Capture Enrichment: Use streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to bind the biotinylated probe-DNA hybrids. Wash away non-hybridized, off-target fragments, leaving an enriched library of exonic sequences.

Sequencing & Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Sequence the enriched library on a short-read platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) to a high depth of coverage (>100x is standard) to ensure confidence in variant calls.

- Data Analysis: The bioinformatics pipeline is similar to WGS (alignment, variant calling), but analysis is focused on the exonic regions. Annotation and prioritization of variants within coding sequences and splice sites are paramount.

Transcriptome Sequencing (RNA-seq)

Transcriptome sequencing analyzes the complete set of RNA transcripts in a cell at a specific point in time, enabling the study of gene expression, alternative splicing, and gene fusions.

RNA-seq provides a quantitative and qualitative profile of the transcriptome. It is pivotal for understanding cellular responses, disease mechanisms, and identifying biomarkers. Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized this field by resolving cellular heterogeneity within complex tissues, uncovering novel and rare cell types, and mapping gene expression in the context of tissue structure (spatial transcriptomics) [23] [24]. Key applications include tumor microenvironment dissection, drug discovery, and developmental biology [23].

Experimental Protocol: Bulk RNA-seq

Library Preparation

- RNA Extraction: Isolve total RNA or mRNA from samples (tissue, cells) using kits that preserve RNA integrity (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy). Assess RNA Quality (e.g., RIN score via Bioanalyzer).

- rRNA Depletion or Poly-A Selection: Enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) by either:

- Poly-A Selection: Use oligo(dT) beads to capture mRNA molecules with poly-A tails.

- rRNA Depletion: Use probes to remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert RNA into double-stranded cDNA using reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase.

- Library Construction: Fragment the cDNA, ligate sequencing adapters, and amplify the final library via PCR.

Sequencing & Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) with paired-end reads (e.g., 2x150 bp) recommended for splicing analysis.

- Data Analysis:

- Quality Control: Assess raw read quality with FastQC.

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome/transcriptome using splice-aware aligners (e.g., STAR, HISAT2).

- Quantification: Count reads aligned to genes/transcripts to create an expression matrix.

- Differential Expression: Use tools like DESeq2 or edgeR to identify significantly differentially expressed genes between conditions.

scRNA-seq Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Products/Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Isolation System | Gently dissociates tissue and isolates individual live cells for downstream processing. | 10x Genomics Chromium Controller, Fluorescent-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) [23] |

| Single-Cell Library Prep Kit | Creates barcoded sequencing libraries from single cells, enabling thousands of cells to be processed in one experiment. | 10x Genomics Single Cell Gene Expression kits [23] |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Breaks open individual cells to release RNA while preserving RNA integrity. | Component of commercial scRNA-seq kits [23] |

| Reverse Transcriptase Master Mix | Converts the RNA from each single cell into stable, barcoded cDNA during the GEM (Gel Bead-in-Emulsion) step. | Component of commercial scRNA-seq kits [23] |

| Barcoded Beads | Microbeads containing cell- and molecule-specific barcodes that uniquely tag all cDNA from a single cell. | 10x Genomics Barcoded Gel Beads [23] |

Epigenomics

Epigenomics involves the genome-wide study of epigenetic modifications—heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve changes to the underlying DNA sequence. Key modifications include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-associated silencing.

Epigenetic aberrations are crucial in tumor diseases, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurological disorders [25]. Clinical sampling for epigenetics can involve tissue biopsies, blood (for cell-free DNA analysis), saliva, and isolated specific cell types (e.g., circulating tumor cells) [25]. HiFi long-read sequencing (PacBio) can now detect base modifications like 5mC methylation simultaneously with standard sequencing, providing phased haplotyping and methylation profiles from a single experiment [26].

Experimental Protocol: DNA Methylation Analysis (Bisulfite Sequencing)

Bisulfite Conversion & Library Prep

- Bisulfite Treatment: Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (which are read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines (5mC) remain unchanged. This creates sequence differences based on methylation status.

- Library Preparation: Prepare a sequencing library from the bisulfite-converted DNA. Specialized kits are available that account for the DNA damage caused by bisulfite treatment.

- Note on Long-Read Methods: With PacBio HiFi sequencing, 5mC detection in CpG contexts is achieved natively without bisulfite conversion, as the polymerase kinetics are sensitive to the modification [26].

Sequencing & Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Sequence the library on an appropriate platform. For whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), this is typically done on an Illumina system.

- Data Analysis:

- Alignment: Use bisulfite-aware aligners (e.g., Bismark, BSMAP) that account for the C-to-T conversion in the reads.

- Methylation Calling: Calculate the methylation ratio at each cytosine position by comparing the number of reads reporting a 'C' (methylated) versus a 'T' (unmethylated).

The Impact of NGS on Genomics Research and Precision Medicine

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed genomics research and clinical diagnostics by enabling the rapid, high-throughput sequencing of DNA and RNA molecules [11]. This technology allows researchers to sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously, providing unprecedented insights into genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications [7]. The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of genomics research, facilitating studies on rare genetic diseases, cancer genomics, microbiome analysis, infectious diseases, and population genetics [27]. NGS has progressed through multiple generations of technological advancement, beginning with first-generation Sanger sequencing, evolving to dominant second-generation short-read platforms, and expanding to include third-generation long-read and real-time sequencing technologies [28] [7]. The continuous innovation in NGS technologies has driven down costs while dramatically increasing speed and accessibility, making large-scale genomic studies and routine clinical applications feasible [24].

NGS Technologies and Platforms

Platform Diversity and Specifications

The NGS landscape features multiple platforms employing distinct sequencing chemistries, each with unique advantages and limitations. Key players include Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis, Thermo Fisher's Ion Torrent semiconductor sequencing, Pacific Biosciences' single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, and Oxford Nanopore's nanopore-based sequencing [7]. These platforms differ significantly in their throughput, read length, accuracy, cost, and application suitability, requiring researchers to carefully match platform capabilities to their specific research goals [28].

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms and Their Capabilities

| Platform | Sequencing Technology | Read Length | Key Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) | 75-300 bp (short) | High accuracy (99.9%), high throughput, low cost per base | Whole genome sequencing, targeted sequencing, gene expression, epigenetics [27] [7] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time | Average 10,000-25,000 bp (long) | Long reads, detects epigenetic modifications | De novo genome assembly, structural variant detection, full-length transcript sequencing [7] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore detection | Average 10,000-30,000 bp (long) | Real-time sequencing, portable options, longest read lengths | Real-time surveillance, field sequencing, structural variation [24] [7] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing | 200-400 bp (short) | Fast run times, simple workflow | Targeted sequencing, small genome sequencing [7] |

| Roche SBX | Sequencing by Expansion | Information Missing | Ultra-rapid, high signal-to-noise, scalable | Whole genome, exome, and RNA sequencing (promised for future applications) [29] |

Emerging Innovations in NGS Technology

The NGS technology landscape continues to evolve with emerging innovations that address limitations of current platforms. In 2025, Roche unveiled its novel Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology, which represents a new approach to NGS [29]. This method uses a sophisticated biochemical process to encode the sequence of a target nucleic acid molecule into a measurable surrogate polymer called an Xpandomer, which is fifty times longer than the original molecule [29]. These Xpandomers encode sequence information into high signal-to-noise reporters, enabling highly accurate single-molecule nanopore sequencing using a Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS)-based sensor module [29]. This technology promises to reduce the time from sample to genome from days to hours, potentially significantly speeding up genomic research and clinical applications [29]. Additionally, advances in long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore are continuously improving accuracy and read length while reducing costs, enabling more comprehensive genome analysis and closing gaps in genomic coverage [30] [7].

NGS Workflow: From Sample to Insight

Standardized Experimental Protocol

The NGS workflow consists of three major stages: (1) template preparation, (2) sequencing and imaging, and (3) data analysis [28]. The following protocol details the critical steps for DNA whole-genome sequencing using Illumina platforms, which can be adapted for other applications and platforms with appropriate modifications.

Template Preparation

Day 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction and Quality Control (2-4 hours)

- Extract DNA from biological samples using validated extraction kits suitable for your sample type (e.g., blood, tissue, cells).

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) to ensure accurate concentration measurement.

- Assess DNA quality through agarose gel electrophoresis or automated electrophoresis systems (e.g., TapeStation, Bioanalyzer). High-quality DNA should show minimal degradation with a DNA Integrity Number (DIN) >7.0.

- Dilute DNA to working concentration in low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water based on library preparation requirements.

Day 1-2: Library Preparation (6-8 hours)

- Fragment DNA to desired size (typically 200-500bp) using enzymatic fragmentation (e.g., tagmentation) or acoustic shearing (e.g., Covaris).

- Perform end-repair and A-tailing to create blunt-ended, 5'-phosphorylated fragments with a single 3'A overhang.

- Ligate adapters containing platform-specific sequences, sample indexes (barcodes), and sequencing primer binding sites using DNA ligase.

- Clean up ligation reaction using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads to remove excess adapters and reaction components.

- Amplify library via limited-cycle PCR (typically 4-10 cycles) to enrich for properly ligated fragments and incorporate complete adapter sequences.

- Perform final library cleanup using SPRI beads to remove PCR reagents and select for appropriate fragment sizes.

- Validate library quality using automated electrophoresis systems to confirm expected size distribution and absence of adapter dimers.

- Quantify final library using fluorometric methods for accurate concentration measurement.

Sequencing and Imaging

Day 2-3: Cluster Generation and Sequencing (1-3 days depending on platform)

- Dilute libraries to appropriate concentration for loading onto flow cell.

- Denature library to create single-stranded DNA templates.

- Load library onto flow cell for cluster generation via bridge amplification.

- Perform sequencing using the appropriate sequencing kit and cycle number for your desired read length.

- For paired-end sequencing: Sequence from both ends of the fragments by performing an additional round of sequencing after fragment reversal.

Data Analysis

Day 3-5: Bioinformatics Processing (Timing varies with computational resources)

- Convert base calls from binary format to FASTQ sequence files.

- Perform quality control on raw reads using FastQC or similar tools.

- Trim adapters and low-quality bases using tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [11].

- Align reads to reference genome using aligners such as BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) or STAR (for RNA-Seq) [11].

- Process aligned reads in BAM format, including sorting, duplicate marking, and local realignment around indels.

- Call variants using appropriate tools (e.g., GATK for SNPs and indels, Manta for structural variants) [11].

- Annotate variants using databases such as dbSNP, gnomAD, ClinVar, and COSMIC to determine functional and clinical significance [11].

- Interpret results in biological and clinical context.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful NGS experiments require high-quality reagents and materials throughout the workflow. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for NGS library preparation and sequencing.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for NGS Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA/RNA Blood Mini Kit, DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA from various sample types | Critical for obtaining high-quality input material; choice depends on sample source and yield requirements |

| Library Preparation Kits | KAPA HyperPrep Kit, Illumina DNA Prep | Fragment DNA, repair ends, add adapters, and amplify library | Kit selection depends on application (WGS, targeted, RNA-Seq) and input DNA quantity/quality |

| Target Enrichment Kits | Illumina Nextera Flex for Enrichment, Twist Target Enrichment | Enrich specific genomic regions of interest | Essential for targeted sequencing; uses hybridization capture or amplicon-based approaches |

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina SBS Kits, PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kit | Provide enzymes, nucleotides, and buffers for sequencing reaction | Platform-specific; determine read length, quality, and output |

| Quality Control Reagents | Qubit dsDNA HS/BR Assay Kits, Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit | Quantify and qualify nucleic acids at various workflow stages | Essential for ensuring library quality before sequencing; prevents failed runs |

| Cleanup Reagents | AMPure XP Beads, ProNex Size-Selective Purification System | Remove enzymes, nucleotides, and short fragments; size selection | SPRI bead-based methods are standard for most cleanup and size selection steps |

| Barcodes/Adapters | Illumina TruSeq DNA UD Indexes, IDT for Illumina Nextera DNA UD Indexes | Enable sample multiplexing and platform compatibility | Unique dual indexes (UDIs) enable higher-plex multiplexing and reduce index hopping |

Clinical Applications and Impact

Precision Oncology Applications

NGS has revolutionized cancer diagnostics and treatment selection through comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors [27]. By identifying somatic mutations, gene fusions, copy number alterations, and biomarkers of therapy response, NGS enables molecularly guided treatment strategies in precision oncology [27]. Key applications in oncology include:

1. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) CGP utilizes large NGS panels (typically 300-500 genes) to simultaneously identify multiple classes of genomic alterations in tumor tissue [27]. This approach replaces sequential single-gene testing, conserving valuable tissue and providing a more complete molecular portrait of the tumor. CGP can identify actionable mutations in genes such as EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, and KRAS, guiding selection of targeted therapies [27]. The FDA-approved AVENIO Tumor Tissue CGP Automated Kit (Roche/Foundation Medicine collaboration) exemplifies the translation of NGS into validated clinical diagnostics [29].

2. Liquid Biopsy and Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Monitoring Liquid biopsy analyzes circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood samples, providing a non-invasive method for cancer detection, therapy selection, and monitoring [27] [31]. These tests can detect tiny fragments of tumor DNA floating in someone's bloodstream, with minimal residual disease (MRD) tests capable of detecting cancer recurrence months before traditional scans would show evidence [31]. Liquid biopsies are particularly valuable when tumor tissue is unavailable or for monitoring treatment response and resistance in real-time [27].

3. Immunotherapy Biomarker Discovery NGS enables identification of biomarkers that predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, including tumor mutational burden (TMB), microsatellite instability (MSI), and PD-L1 expression [27]. High TMB (typically ≥10 mutations/megabase) correlates with improved response to immunotherapy across multiple cancer types, and NGS panels can simultaneously assess TMB while detecting other actionable alterations [27].

Rare Disease Diagnostics

NGS has dramatically improved the diagnostic yield for rare genetic disorders, which often involve heterogeneous mutations across hundreds of genes [24]. Whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) can identify pathogenic variants in previously undiagnosed cases, ending diagnostic odysseys for patients and families [24]. Rapid whole-genome sequencing (rWGS) has shown particular utility in neonatal and pediatric intensive care settings, where rapid diagnosis can directly impact acute management decisions [24]. The ability to simultaneously analyze trio samples (proband and parents) enhances variant interpretation by establishing inheritance patterns and de novo mutation rates [11].

Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Therapeutics

NGS facilitates personalized drug therapy by identifying genetic variants that influence drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity [24] [31]. Pharmacogenomic profiling using targeted NGS panels can detect clinically relevant variants in genes such as CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, VKORC1, and TPMT, guiding medication selection and dosing [31]. This approach minimizes adverse drug reactions and improves therapeutic outcomes by aligning treatment with individual genetic profiles [24].

Future Directions and Challenges

Emerging Trends in NGS Technology

The NGS field continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping its future development and application. A significant shift is occurring toward multi-omics integration, combining genomic data with transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic information from the same sample [24] [30] [31]. This approach provides a more comprehensive view of biological systems, linking genetic information with molecular function and phenotypic outcomes [24]. The multi-omics market is projected to grow substantially from USD 3.10 billion in 2025 to USD 12.65 billion by 2035, reflecting increased adoption [31].

Spatial transcriptomics and single-cell sequencing represent another frontier, enabling researchers to explore cellular heterogeneity and gene expression patterns within tissue architecture [24] [30]. These technologies allow direct sequencing of genomic variations such as cancer mutations and immune receptor sequences in single cells within their native spatial context in tissue, empowering exploration of complex cellular interactions and disease mechanisms with unprecedented precision [30]. The year 2025 is expected to see increased routine 3D spatial studies to comprehensively assess cellular interactions in the tissue microenvironment [30].

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly integrated into NGS data analysis, enhancing variant detection, interpretation, and biological insight extraction [24] [30]. AI-powered tools like Google's DeepVariant utilize deep learning to identify genetic variants with greater accuracy than traditional methods [24]. Machine learning models analyze polygenic risk scores to predict individual susceptibility to complex diseases and accelerate drug discovery by identifying novel therapeutic targets [24].

Addressing Implementation Challenges

Despite rapid advancements, several challenges remain for widespread NGS implementation in research and clinical settings. Data management and analysis present significant hurdles, with each human genome generating approximately 100 gigabytes of raw data [11] [31]. The massive scale and complexity of genomic datasets demand advanced computational tools, cloud computing infrastructure, and bioinformatics expertise [11] [24]. Cloud platforms such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Genomics provide scalable solutions for storing, processing, and analyzing large genomic datasets while ensuring compliance with regulatory frameworks like HIPAA and GDPR [24].

Cost and accessibility issues persist, particularly for comprehensive genomic tests and in resource-limited settings [27] [32]. While the cost of whole-genome sequencing has dropped dramatically to approximately $200 per genome on platforms like Illumina's NovaSeq X Plus, the total cost of ownership including instrumentation, reagents, and computational infrastructure remains substantial [32]. Efforts to democratize access through streamlined workflows, automated library preparation (e.g., Roche's AVENIO Edge system), and decentralized manufacturing for cell and gene therapies are helping to address these barriers [24] [29].

Interpretation of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) and standardization of clinical reporting continue to challenge the field [27]. As more genes are sequenced across diverse populations, the number of identified VUS increases, creating uncertainty for clinicians and patients [27]. Developing more sophisticated functional annotation tools, aggregating data across institutions, and implementing AI-driven interpretation platforms will be essential for improving variant classification [27] [30].

The United States NGS market reflects these dynamic trends, with projections indicating substantial growth from US$3.88 billion in 2024 to US$16.57 billion by 2033, driven by personalized medicine applications, research expansion into agriculture and environmental sciences, and continued technological advancements in automation and data analysis [32]. This growth trajectory underscores the transformative impact NGS continues to have across biomedical research and clinical practice.

NGS in Action: Techniques and Transformative Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research by enabling the massively parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, providing ultra-high throughput, scalability, and speed at a fraction of the cost and time of traditional methods [10] [4]. This transformative technology has made large-scale whole-genome sequencing accessible and practical for average researchers, shifting from the decades-old Sanger sequencing method that could only read one DNA fragment at a time [10] [28]. The NGS workflow encompasses all steps from biological sample acquisition through computational data analysis, with each phase being critical for generating accurate, reliable genetic information [33] [28]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the end-to-end NGS workflow, detailed protocols, and current technological applications framed within the context of DNA and RNA analysis for research and drug development.

The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of genomics research across diverse domains including clinical diagnostics, cancer genomics, rare genetic diseases, microbiome analysis, infectious diseases, and population genetics [7]. By allowing researchers to rapidly sequence entire genomes, deeply sequence target regions, analyze epigenetic factors, and quantify gene expression, NGS has become an indispensable tool for precision medicine approaches and targeted therapy development [24] [4]. The continuous evolution of NGS technologies has driven consistent improvements in sequencing accuracy, read length, and cost-effectiveness, supporting increasingly sophisticated applications in both basic research and clinical settings [7].

The fundamental NGS workflow consists of three primary stages: (1) sample preparation and library construction, (2) sequencing, and (3) data analysis [28] [4]. This process transforms biological samples into interpretable genetic information through a coordinated series of molecular and computational steps. The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow:

Figure 1: Comprehensive overview of the end-to-end NGS workflow from sample acquisition to data analysis, highlighting the four major stages with their key components.

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

Nucleic Acid Extraction

The initial step in every NGS protocol involves extracting high-quality nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) from biological samples [33]. The quality of extracted nucleic acids directly depends on the quality of the starting material and appropriate sample storage, typically involving freezing at specific temperatures [33].

Protocol: Nucleic Acid Extraction from Blood Samples

- Sample Lysis: Add 20 mL of blood to 30 mL of red blood cell lysis buffer, mix by inversion, and incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature. Centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes and discard supernatant [33].

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend pellet in 10 mL of cell lysis buffer with proteinase K, mix thoroughly, and incubate at 56°C for 60 minutes with occasional mixing [33].

- RNA Separation: For RNA extraction, add RNA-specific binding buffers and purify using spin-column technology. For DNA, proceed with organic extraction [33].

- Precipitation and Washing: Add equal volume of isopropanol to precipitate nucleic acids. Centrifuge at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes, wash pellet with 70% ethanol, and air dry for 10 minutes [33].

- Elution: Resuspend nucleic acid pellet in 50-100 μL of TE buffer or nuclease-free water. Quantify using fluorometric methods and assess quality by agarose gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer [33].

The success of downstream sequencing applications critically depends on optimal nucleic acid quality. Common challenges include sample degradation, contamination, and insufficient quantity, which can be mitigated through proper handling, use of nuclease-free reagents, and working in dedicated pre-amplification areas [33].

Library Preparation

Library preparation converts the extracted nucleic acids into a format compatible with sequencing platforms through fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification [33] [28]. Different applications require specific library preparation methods:

Protocol: DNA Library Preparation for Illumina Platforms

- Fragmentation: Fragment 100-500 ng of genomic DNA to 200-500 bp fragments using enzymatic digestion (e.g., fragmentase) or acoustic shearing. Verify fragment size using agarose gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer [28].

- End Repair and A-Tailing: Repair fragment ends using a combination of T4 DNA polymerase and Klenow fragment to create blunt ends. Add single A-overhangs using Klenow exo- polymerase to facilitate adapter ligation [33] [28].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific adapters containing sequencing primer binding sites and sample barcodes using T4 DNA ligase. Purify ligated products using magnetic beads to remove unincorporated adapters [28].

- Library Amplification: Amplify adapter-ligated fragments using 4-12 cycles of PCR with high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Incorporate complete adapter sequences and sample indexes during amplification [33].

- Library Quantification and Normalization: Quantify final library using qPCR and determine size distribution using bioanalyzer. Normalize libraries to 4 nM and pool if multiplexing [33].

For RNA sequencing, the workflow includes additional steps such as mRNA enrichment using poly-A selection or rRNA depletion, followed by reverse transcription to cDNA before library construction [33]. The introduction of tagmentation reactions, which combine fragmentation and adapter attachment into a single step, has significantly reduced library preparation time and costs [33].

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Library Preparation Methods for Different Applications

| Application | Starting Material | Key Preparation Steps | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Genomic DNA | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, PCR amplification | High DNA integrity crucial; avoid amplification bias |

| Whole Exome Sequencing | Genomic DNA | Fragmentation, hybrid capture with exome probes, PCR | Efficient target enrichment critical for coverage uniformity |

| RNA Sequencing | Total RNA or mRNA | Poly-A selection/rRNA depletion, reverse transcription, cDNA synthesis | Strand-specific protocols preserve transcript orientation |

| Targeted Sequencing | Genomic DNA | Fragmentation, hybrid capture or amplicon generation, PCR | High coverage depth required for rare variant detection |

| Single-Cell Sequencing | Single cells | Cell lysis, reverse transcription, whole transcriptome amplification | Address amplification bias from minimal starting material |

Sequencing Platforms and Technologies

Sequencing Technologies

NGS platforms utilize different biochemical principles for sequencing, with the most common being sequencing by synthesis (SBS) [28] [4]. The key technologies include:

Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS): This method, employed by Illumina platforms, uses fluorescently-labeled reversible terminator nucleotides that are added sequentially to growing DNA chains [28] [4]. Each nucleotide incorporation event is detected through fluorescence imaging, with the terminator cleavage allowing the next cycle to begin. Recent advances like XLEAP-SBS chemistry have increased speed and fidelity compared to standard SBS chemistry [4].

Semiconductor Sequencing: Used by Ion Torrent platforms, this technology detects hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization rather than using optical detection [28]. When a nucleotide is incorporated into a growing DNA strand, a hydrogen ion is released, changing the local pH that is detected by a semiconductor sensor [28].

Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing: Developed by Pacific Biosciences, this third-generation technology observes DNA synthesis in real-time using zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [7]. The technology provides exceptionally long read lengths (average 10,000-25,000 bp) that are valuable for resolving complex genomic regions, though with higher per-base error rates than short-read technologies [7].

Nanopore Sequencing: Oxford Nanopore Technologies' method involves measuring changes in electrical current as DNA molecules pass through protein nanopores [7]. This technology can produce ultra-long reads (average 10,000-30,000 bp) and enables real-time data analysis, though it historically has higher error rates (up to 15%) [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms and Technologies (2025)

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Accuracy | Throughput per Run | Run Time | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Sequencing by Synthesis | 50-300 bp | >99.9% | Up to 16 Tb | 13-44 hours | Large WGS, population studies |

| PacBio Revio | SMRT Sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp | >99.9% (after correction) | 360-1080 Gb | 0.5-30 hours | De novo assembly, structural variants |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore Sequencing | 10,000-30,000+ bp | ~99% (after correction) | 10-320 Gb | 0.5-72 hours | Real-time sequencing, metagenomics |

| Ion Torrent Genexus | Semiconductor Sequencing | 200-400 bp | >99.5% | 50 Mb-1.2 Gb | 8-24 hours | Targeted sequencing, rapid diagnostics |

| Element AVITI | Sequencing by Synthesis | 50-300 bp | >99.9% | 20 Gb-1.2 Tb | 12-40 hours | RNA-seq, exome sequencing |

Platform Selection Considerations

Choosing the appropriate NGS platform depends on multiple factors including research objectives, required throughput, read length, accuracy needs, and budget constraints [28]. Benchtop sequencers are ideal for small-scale studies and targeted panels, while production-scale systems are designed for large genome projects and high-volume clinical testing [28].

Recent advancements include the launch of Illumina's NovaSeq X Series, which provides extraordinary sequencing power with increased speed and sustainability, capable of producing over 20,000 whole genomes annually [4]. The ongoing innovation in sequencing chemistry, such as the development of XLEAP-SBS with twice the speed and three times the accuracy of previous methods, continues to push the boundaries of what's possible with NGS technology [4].

Data Analysis Workflow

Primary and Secondary Analysis

The NGS data analysis workflow consists of multiple stages that transform raw sequencing data into biological insights [28]. The massive volume of data generated by NGS platforms (often terabytes per project) requires sophisticated computational infrastructure and bioinformatics expertise [24] [28].

Primary Analysis involves base calling, demultiplexing, and quality control. Raw signal data (images or electrical measurements) are converted into sequence reads (FASTQ files) with associated quality scores [28]. Quality control metrics include per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and overall read quality, with tools like FastQC commonly used for this purpose.

Protocol: Primary Data Analysis and QC

- Base Calling: Convert raw signal data to nucleotide sequences using platform-specific algorithms. Generate FASTQ files containing sequences and quality scores [28].

- Demultiplexing: Separate pooled samples using barcode sequences assigned during library preparation. Assign reads to individual samples based on unique barcodes [28].

- Quality Control: Assess read quality using FastQC or similar tools. Trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic or Cutadapt. Remove poor-quality reads (Q-score < 20) [28].

Secondary Analysis encompasses read alignment and variant calling. Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome (BAM files), followed by identification of genetic variants (VCF files) [28].

Protocol: Secondary Analysis - Alignment and Variant Calling

- Read Alignment: Map quality-filtered reads to reference genome using aligners like BWA-MEM or Bowtie2. For RNA-seq data, use splice-aware aligners such as STAR [34] [28].

- Post-Alignment Processing: Sort and index aligned BAM files. Mark PCR duplicates using tools like Picard MarkDuplicates to minimize amplification bias [33] [28].

- Variant Calling: Identify genetic variants (SNPs, indels) using callers like GATK HaplotypeCaller or DeepVariant. For tumor samples, use MuTect2 for somatic variant detection [24] [34].

- Variant Filtering: Apply quality filters based on read depth, mapping quality, and variant frequency. Remove low-confidence calls to minimize false positives [34].

Tertiary Analysis and Interpretation

Tertiary analysis focuses on biological interpretation through variant annotation, pathway analysis, and data visualization [28]. This stage extracts meaningful biological insights from variant data by connecting genetic changes to functional consequences.

Protocol: Tertiary Analysis and Biological Interpretation