Mitigating RNAi Off-Target Effects: A Strategic Guide for Robust Experimental Design and Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of off-target effects in RNA interference (RNAi) experiments.

Mitigating RNAi Off-Target Effects: A Strategic Guide for Robust Experimental Design and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of off-target effects in RNA interference (RNAi) experiments. It explores the fundamental mechanisms behind these effects, including miRNA-like seed region binding and immune activation. The content details practical methodologies for designing specific RNAi triggers, from bioinformatic tools to chemical modifications. It further offers troubleshooting strategies for optimizing experimental conditions and validation frameworks to confirm on-target activity. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with advanced application and validation techniques, this guide aims to empower scientists to enhance the reliability of their functional genomics data and accelerate the development of safer, more effective RNAi-based therapeutics.

Deconstructing RNAi Off-Target Effects: Mechanisms, Sources, and Impact on Data Fidelity

FAQs: Understanding Off-Target Effects in RNAi

What are off-target effects in RNAi experiments? Off-target effects occur when your RNAi molecules, such as siRNA or miRNA, silence genes other than the intended target. This happens primarily through two mechanisms: sequence-dependent effects, where the guide strand has partial complementarity to non-target mRNAs (similar to how endogenous miRNAs function), and sequence-independent effects, where the RNAi molecules trigger innate immune responses, such as the interferon pathway [1] [2]. These effects can confound experimental results by producing misleading phenotypes and pose significant safety risks in therapeutic development.

Why should I be concerned about off-target effects? Off-target effects are a major concern because they can compromise the validity of your experimental data and the safety of potential therapeutics. In research, they can lead to incorrect conclusions about gene function [1]. In drug development, off-target activity can result in unexpected toxicities and adverse events, potentially halting the progression of promising RNAi drug candidates [2]. Managing these effects is therefore critical for both basic research success and clinical application.

How do RNAi off-target effects differ from those in CRISPR/Cas9? While both technologies face off-target challenges, their fundamental mechanisms differ. RNAi causes gene knockdown at the mRNA level, and its off-targets are often due to partial sequence complementarity, especially in the "seed region" (nucleotides 2-8 of the guide strand), leading to the degradation or translational repression of non-target mRNAs [3] [1]. In contrast, CRISPR/Cas9 creates permanent knockout mutations at the DNA level. Its off-target effects typically involve Cas9 cleaving genomic sites with sequence similarity to the guide RNA, potentially causing chromosomal rearrangements or unintended mutations [4] [5]. Recent comparative studies suggest that well-optimized CRISPR/Cas9 systems can have fewer off-target effects than RNAi [1].

What are the main strategies to minimize off-target effects? You can employ several key strategies to reduce off-target effects:

- Careful Oligo Design: Use bioinformatics tools to design siRNAs with high specificity, ensuring minimal sequence homology to other genes in the target organism [6] [7].

- Chemical Modifications: Utilize advanced chemistries like Stealth RNAi, which incorporate proprietary modifications to ensure only the antisense strand enters the RISC and to enhance stability, thereby reducing off-target potential [6].

- Optimal Concentration: Use the lowest effective concentration of siRNA during transfection, as high concentrations increase the likelihood of off-target binding [8].

- Pooling Strategies: Using pooled siRNAs can help dilute out individual sequences with high off-target potential, though this must be balanced with the ability to identify the specific effective sequence [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Off-Target Effects

Problem: Suspected Phenotype from Off-Target Effects

Symptoms:

- Observed phenotypic effects that do not align with the known function of your target gene.

- Inconsistent results between different siRNA sequences designed for the same target gene.

- Failure to rescue the phenotype by expressing a target gene construct that is resistant to RNAi (e.g., with silent mutations).

Solutions:

- Validate with Multiple siRNAs: The most reliable approach is to test at least two or three distinct siRNA sequences targeting different regions of the same mRNA. If all independent siRNAs produce the same phenotypic result, it is more likely to be an on-target effect [8].

- Perform a Rescue Experiment: Co-transfect your siRNA with a plasmid expressing the target gene that has been engineered with silent mutations in the siRNA-binding site. This "recoded" gene will be resistant to RNAi. If the phenotype is reversed, it confirms on-target activity; if not, an off-target effect is likely.

- Conduct Transcriptomic Analysis: Use genome-wide expression profiling (e.g., RNA-seq) to compare cells treated with your siRNA to control cells. This will directly reveal which genes are being unexpectedly up or down-regulated, providing a map of potential off-targets [1].

- Measure Protein Levels: Always confirm knockdown at the protein level (e.g., by Western blot) in addition to mRNA levels. Persistent protein expression despite mRNA reduction could indicate a potent off-target effect driving the phenotype [6].

Problem: Poor Gene Knockdown Efficiency

Symptoms:

- Minimal reduction in target mRNA or protein levels after siRNA transfection.

- No observable phenotypic change.

Solutions:

- Check Transfection Efficiency: Ensure your siRNA is successfully entering the cells. Use a fluorescently labeled control siRNA (e.g., BLOCK-iT Fluorescent Oligo) and monitor uptake under a microscope. Optimize transfection parameters like reagent concentration, cell confluency, and complex formation time [8] [6].

- Verify Oligo Sequence and Quality: Sequence your siRNA or shRNA expression plasmid to confirm the insert is correct and has not acquired mutations during cloning. Use high-quality, HPLC- or PAGE-purified oligonucleotides [8].

- Re-design siRNA/shRNA: The initial target site or hairpin design may be suboptimal. Use a proprietary algorithm (e.g., RNAi Designer) to select a new target region with proven efficacy. For shRNAs, you can also try varying the stem length or loop sequence [8] [6].

- Switch Delivery Method: If using synthetic siRNA, consider switching to a viral delivery system (e.g., lentiviral shRNA) for more robust and sustained expression, especially in hard-to-transfect cells [6].

Key Reagents and Experimental Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Reducing Off-Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Stealth RNAi [6] | Chemically modified siRNA duplex. | Proprietary modifications ensure only the antisense strand loads into RISC, reducing off-targeting from the sense strand. |

| Bioinformatics Design Tools (e.g., RNAi Designer) [6] | In silico design of siRNA sequences. | Uses algorithms to ensure sequence uniqueness and minimize homology to other genes in the selected organism. |

| Lentiviral shRNA Vectors [6] | Stable, long-term gene knockdown. | Allows generation of stable cell pools, minimizing clonal variation and enabling validation across multiple cell populations. |

| Inducible shRNA Systems (e.g., H1/TO promoter) [6] | Precise temporal control of shRNA expression. | Enabling short-term induction of RNAi can limit the duration of exposure, reducing the accumulation of off-target effects. |

| Control siRNAs (e.g., Scrambled, Non-targeting) [4] | Baseline for experimental comparisons. | Serves as a transfection control but is not a perfect off-target control, as different sequences have different off-target profiles. |

Protocol: Validating Knockdown Specificity

Purpose: To confirm that an observed phenotypic effect is due to on-target gene silencing and not off-target effects.

Materials:

- Validated siRNA sequences (at least 2-3) targeting your gene of interest.

- Non-targeting control siRNA.

- Plasmid for rescue experiment (target gene cDNA with silent mutations in the siRNA target site).

- Transfection reagent.

- Reagents for qRT-PCR and Western blotting.

Procedure:

- Transfert your target cells in separate wells with the different siRNAs and the non-targeting control.

- Assay for Phenotype: 48-72 hours post-transfection, assay for the phenotypic change of interest (e.g., cell viability, migration, differentiation).

- Confirm Knockdown: In parallel, harvest cells to confirm knockdown of the target mRNA (via qRT-PCR) and protein (via Western blot).

- Rescue Experiment: Co-transfect the most effective siRNA alongside the rescue plasmid expressing the mutated, RNAi-resistant target gene. Include controls with the rescue plasmid alone and the siRNA alone.

- Re-assay for Phenotype: 48-72 hours later, re-assay for the phenotypic change.

Interpretation: If the phenotype is consistently observed with all specific siRNAs and is reversed by the expression of the RNAi-resistant rescue construct, it is strong evidence for an on-target effect. Inconsistency between siRNAs or a failure to rescue suggests off-target activity.

Protocol: Detecting Transcriptome-Wide Off-Target Effects

Purpose: To identify all genes whose expression is inadvertently altered by your RNAi treatment.

Materials:

- Cells treated with siRNA and appropriate controls.

- RNA extraction kit.

- RNA-seq library prep kit and sequencing service.

Procedure:

- Treat and Harvest: Transfert cells with your target siRNA and a non-targeting control siRNA. Harvest total RNA 48 hours post-transfection. Perform this in biological triplicate.

- RNA Sequencing: Check RNA quality, prepare sequencing libraries, and perform RNA-seq on all samples.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Map sequencing reads to the reference genome.

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the target siRNA and control siRNA samples.

- Filter the DEG list to focus on genes with partial complementarity to the siRNA's "seed region" (nucleotides 2-8 of the guide strand), as these are the most likely direct off-targets.

Interpretation: A large number of differentially expressed genes, particularly those with seed region matches to your siRNA, indicates significant off-target activity. This data can be used to re-design a more specific siRNA.

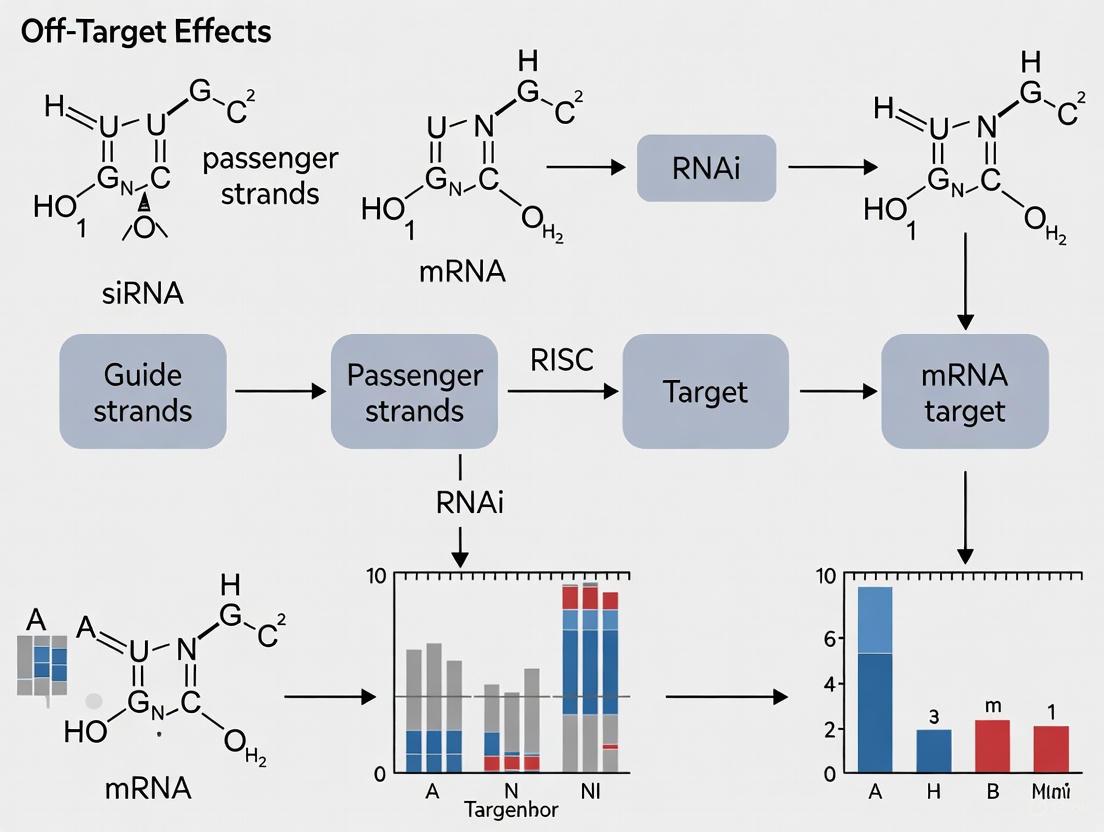

Visualizing the Pathways and Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the core RNAi mechanism and highlights where two major types of off-target effects can occur.

Experimental Workflow for Specific RNAi

This workflow outlines the key steps for conducting an RNAi experiment with built-in checks to identify and mitigate off-target effects.

MicroRNA (miRNA) mimicry has emerged as a powerful therapeutic strategy to restore the function of tumor-suppressing miRNAs that are frequently downregulated in diseases like cancer. The efficacy of these synthetic miRNA-like duplexes hinges on a fundamental principle: seed region complementarity. The seed region, a conserved sequence at the 5' end of the miRNA guide strand (typically nucleotides 2-8), is the primary determinant for recognizing and binding to target mRNAs [9] [10]. This binding, even with imperfect complementarity outside the seed region, can lead to translational repression or degradation of the target mRNA [10] [11]. While this mechanism allows a single miRNA to regulate a broad network of genes, it also introduces a significant risk of off-target effects, where the mimic unintentionally represses genes with complementary sequences in their 3' untranslated regions (3' UTRs) [12]. This technical support center provides a framework for understanding and troubleshooting these challenges to ensure the precision and success of your RNAi experiments.

FAQs on miRNA Mimicry and Seed Regions

What is the seed sequence of a miRNA and why is it so important?

The seed sequence is a conserved heptametrical sequence, mostly situated at positions 2-7 from the miRNA's 5' end [9]. This region is essential because it must be perfectly complementary for the initial binding of the miRNA to its target mRNA. It serves as the primary anchor for target recognition, directing the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) to its mRNA targets [10] [11].

How do off-target effects occur with miRNA mimics, and how do they differ from siRNA off-targets?

Off-target effects in miRNA mimicry are predominantly seed-mediated. When a synthetic mimic is introduced into a cell, its seed region can bind to the 3' UTRs of mRNAs that were not the intended primary targets, leading to their repression in a miRNA-like fashion [12]. While siRNAs are designed for perfect complementarity to a single target and can cause off-target effects through similar seed-mediated mechanisms, miRNA mimics are designed to leverage the natural, seed-dependent, multi-target regulatory network of endogenous miRNAs [11]. This makes the management of their off-target profile a central consideration.

What computational tools can help predict seed-mediated off-target effects?

SeedMatchR is an R package specifically developed to detect and visualize seed-mediated off-target effects of siRNA and miRNA using RNA-seq data [12]. It extends differential expression analysis tools by annotating results with predicted seed matches and provides statistical functions to test for cumulative changes in gene expression attributed to seed region activity.

Can chemical modifications to the mimic reduce off-target effects?

Yes, strategic chemical modifications can mitigate off-target effects. Research has shown that modifications like a glycol nucleic acid (GNA) at position 7 (g7) of the seed region can significantly reduce cumulative off-target gene expression changes and associated toxicities, such as hepatotoxicity in rodent models, without completely abolishing on-target efficacy [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Suspected Widespread Off-Target Effects in Transcriptomic Data

Problem: RNA-seq analysis after miRNA mimic transfection shows a significant, unintended downregulation of a large set of genes.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm Effect | Run an ECDF (Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function) analysis on log2(fold change) data for genes with/without a seed match. | A significant leftward shift (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) in the ECDF of genes with a seed match indicates a cumulative seed-mediated off-target effect [12]. |

| 2. Use Controls | Always include a scrambled sequence control mimic in experiments. | This helps distinguish sequence-specific effects from non-specific cellular responses to nucleic acid transfection [13]. |

| 3. Analyze Seed Context | Use tools like SeedMatchR to annotate your DE results with the number of seed matches in gene 3' UTRs. | This statistically tests if differential expression is associated with the presence of a seed match in the 3' UTR, confirming a seed-driven mechanism [12]. |

| 4. Optimize Dosage | Perform a dose-response curve and use the lowest effective concentration. | Suprapharmacological doses of RNAi triggers exacerbate seed-mediated off-target effects; using minimal effective dose mitigates this [12]. |

Issue 2: Lack of Intended On-Target Effect

Problem: The miRNA mimic fails to knock down the expression of its validated primary target genes.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Verify Delivery | Include a fluorescently-labeled control oligonucleotide to assess transfection efficiency. | If delivery failed, no knockdown will occur. This is a critical first step, especially in hard-to-transfect cells [13]. |

| 2. Check Expression | Confirm via qPCR that your target gene is expressed in the cell type used. | There is nothing to knock down if the target is not expressed in your model system [13]. |

| 3. Validate Mimic Design | Ensure the mimic's guide strand is the correct, biologically active sequence for the intended miRNA. | Using the passenger strand or an incorrect sequence will not produce the desired effect. Consult miRBase for canonical sequences. |

| 4. Try Consensus Mimics | Consider using a synthetic mimic based on a family consensus sequence. | For miRNA families (e.g., miR-15/107), a consensus-based mimic can exhibit enhanced growth inhibitory activity and target suppression compared to a native sequence mimic [14]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and tools essential for studying and implementing miRNA mimicry pathways.

| Reagent/Tool | Function & Application in miRNA Research |

|---|---|

| SeedMatchR [12] | An R package for identifying seed-mediated off-target effects from RNA-seq data. It annotates genes with seed matches and performs statistical tests on expression shifts. |

| Synthetic Consensus Mimics [14] | Engineered miRNA mimics based on the consensus sequence of a miRNA family (e.g., miR-15/107). They can offer enhanced therapeutic activity and broader target inhibition. |

| EGFR-Targeted Nanocells (EDV) [14] | A delivery system (e.g., EnGeneIC Dream Vector) that packages miRNA mimics and uses targeting moieties (e.g., against EGFR) for direct, efficient tumor cell delivery in vivo. |

| AUMantagomir sdASO [13] | A self-delivering antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) protocol for microRNA inhibition. Useful as a control to block endogenous miRNA function or to study mimic specificity. |

| Chemically Modified Mimics [12] | Mimics with specific chemical modifications (e.g., GNA at seed position g7) designed to reduce seed-mediated hepatotoxicity and other off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Detecting Seed-Mediated Off-Target Effects with SeedMatchR

This protocol leverages the SeedMatchR package to analyze RNA-seq data from experiments involving miRNA mimics [12].

Inputs Required:

- A data frame of differential expression results (e.g., from DESeq2).

- A species-specific GTF file as a GRanges object.

- A species-specific DNAStringSet for genomic DNA.

- The siRNA/miMic guide sequence (≥ 8 nt).

Procedure:

- Visualize Seed Regions: Use the

plot_seeds()function to plot the miRNA mimic sequence and its default seed definitions. - Prepare Annotations: Generate the required GRanges and DNAStringSet objects from public databases (e.g., ENSEMBL) using built-in Bioconductor functions.

- Run SeedMatchR: Execute the primary

SeedMatchR()function. This function usesvcountpattern()to search the genomic annotations (focusing on 3' UTRs) for matches to the mimic's seed region and annotates your differential expression results with the count of matches per gene. - Statistical Analysis & Visualization:

- Use

de_fc_ecdf()to plot the Empirical Cumulative Distribution Functions (ECDFs) for the log2 fold changes of two gene sets: those with a seed match and those without. - Use

ecdf_stat_test()to perform a one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. A significant result indicates that the distribution of log2 fold changes for genes with a seed match is shifted towards downregulation compared to the background, confirming a cumulative seed-mediated off-target effect.

- Use

Workflow Diagram: miRNA Mimic Off-Target Analysis

Pathway Diagram: miRNA Mimic Mechanism & Seed-Mediated Off-Targets

RNA interference (RNAi) is a powerful tool for gene silencing, but its application is complicated by off-target effects that extend beyond the well-characterized seed-sequence-mediated miRNA-like effects. This technical support guide addresses two other major sources of experimental confounding: the activation of the innate immune response by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and the saturation of the endogenous RNAi machinery. Understanding these phenomena is crucial for designing robust RNAi experiments and accurately interpreting their results.

FAQs: Understanding the Core Challenges

Q1: How can dsRNA, the core trigger of RNAi, also confound my experiment through immune activation?

Double-stranded RNA is recognized by the mammalian innate immune system as a potential sign of viral infection. This triggers defense mechanisms that can mask or mimic your experimental phenotype.

Immune Sensing Pathways: Cytoplasmic dsRNA is primarily detected by two classes of sensors [3] [15]:

- RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs): RIG-I is activated by short dsRNAs with 5' triphosphates (ppp-dsRNA) or cap0 structures, leading to inflammatory signaling via the mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) protein and resulting in interferon and cytokine production [15].

- PKR and OAS/RNase L: These sensors recognize the presence of the RNA duplex itself, independent of 5' end modifications. PKR activation leads to a global shutdown of protein synthesis, while OAS/RNase L activation causes non-specific degradation of cellular RNA [15].

Consequences for Experiments: Activation of these pathways can lead to general cell growth inhibition, cytotoxicity, and widespread changes in gene expression that are independent of your specific target knockdown. This can create false positives or obscure genuine phenotypic effects [15] [16].

Q2: What does it mean for an RNAi experiment to "saturate the endogenous machinery," and why is it harmful?

The cellular machinery that processes your introduced short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) or siRNAs is the same machinery required for the biogenesis and function of endogenous microRNAs (miRNAs). At high concentrations, your experimental RNAi triggers can overwhelm this shared pathway.

- Shared Limiting Factors: Key components like Exportin-5 (responsible for nuclear export of small RNA precursors) and Dicer (which processes dsRNA) can become rate-limiting [16].

- Phenotypic Impact: Saturation leads to a global disruption of endogenous miRNA-regulated gene networks. This can cause severe toxicity, as demonstrated in studies where high-dose shRNA expression in mice led to fatality, not from immune activation or specific off-targets, but from the collapse of essential miRNA functions [16].

- Distinguishing Feature: Unlike sequence-specific off-targets, saturation effects are largely sequence-independent. If multiple, distinct shRNAs against different targets cause similar toxic phenotypes at high doses, saturation of the machinery is a likely cause [16].

Q3: Are there specific experimental factors that make my system more prone to these effects?

Yes, several experimental parameters significantly influence your risk:

- Delivery Method and Dose: The use of viral vectors (especially for shRNA delivery) that lead to very high, persistent expression greatly increases the risk of both immune activation and saturation [16] [17]. Using the lowest possible effective dose of siRNA or shRNA is critical.

- dsRNA Structure and Modification: The immunogenicity of dsRNA is heavily influenced by its 5' end. Triphosphorylated (ppp) dsRNA and cap0 dsRNA are highly immunogenic, while cap1 dsRNA (with a 2'-O-methylation on the first transcribed nucleotide) is effectively masked from RIG-I and evades this inflammatory response [15].

- Cell Type: Different cell lines may have varying basal levels of immune pathway components and miRNA machinery, affecting their sensitivity to these off-target effects.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Suspected Innate Immune Response Activation

Observed Symptoms: Unexplained cell death or growth inhibition; activation of interferon-stimulated genes in transcriptomic data; global translational shutdown; general inflammation in animal models.

| Diagnostic Check | Experimental Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Test for Interferon Response: Measure mRNA levels of classic interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) like OAS1 or MX1 via qRT-PCR 24-48 hours after transfection/transduction [16]. | Use Chemically Modified or Cap1 dsRNA: When generating dsRNA in vitro, use methods that produce a cap1 5' structure to avoid RIG-I recognition [15]. | The cap1 structure (5' end with 2'-O-methylation) is a self-marker. Human dsRNA sensors like RIG-I do not recognize it as "non-self," preventing inflammatory pathway activation [15]. |

| Check for PKR Activation: Monitor for phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) by Western blot, a downstream target of activated PKR. | Titrate RNAi Trigger Dose: Systematically reduce the concentration of siRNA/shRNA to the minimum required for effective knockdown [18] [19]. | Lower concentrations of dsRNA are less likely to reach the threshold required to activate the OAS/RNase L and PKR pathways, which are primarily sensitive to the presence of the duplex [15]. |

| Use Control RNAs: Include controls with known immunostimulatory (e.g., triphosphorylated dsRNA) and non-immunostimulatory (e.g., cap1 dsRNA) structures [15]. | Select Non-Immunostimulatory Sequences: Some sequence motifs can trigger immune responses. Use design tools to avoid these and employ pooled siRNAs to distribute the load [3] [18]. | Pooling multiple siRNAs against the same target allows you to use lower concentrations of each individual sequence, reducing the risk of any single siRNA triggering an immune sensor. |

Problem 2: Suspected Saturation of Endogenous RNAi Machinery

Observed Symptoms: Lethality or severe toxicity in vivo at high shRNA doses; disruption of normal cellular development and function; similar toxic phenotypes from multiple, unrelated shRNAs.

| Diagnostic Check | Experimental Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Monitor miRNA Function: Quantify the expression and activity of abundant endogenous miRNAs (e.g., let-7, miR-21) in treated vs. control cells [16]. A drop in mature miRNA levels or activity indicates saturation. | Use miRNA-Embedded shRNA Platforms: Express your shRNA within a native miRNA backbone (e.g., the Multi-miR platform) [20]. | Endogenous miRNA precursors are naturally optimized for efficient processing without saturating Exportin-5 or Dicer. Embedding your shRNA in this context exploits this natural efficiency [20]. |

| Assess Exportin-5 Dependence: Co-express Exportin-5. If this improves knockdown efficiency or reduces toxicity, it was likely a limiting factor [16]. | Switch to siRNA or Optimized shRNA Designs: For transient knockdown, use siRNAs, which bypass early steps of the miRNA pathway. For stable expression, use polymerase II-driven, miRNA-embedded shRNAs rather than simple Pol III-driven shRNAs [16] [20]. | siRNAs are directly loaded into RISC, bypassing the nuclear Exportin-5 and Dicer processing steps. This places less burden on the core miRNA biogenesis machinery [16]. |

| Perform Dose-Response Studies: Test a range of vector doses (MOI) or expression levels. Toxicity that is only apparent at high doses strongly suggests saturation. | Employ Inducible Expression Systems: Use tetracycline/doxycycline-inducible promoters to control the timing and level of shRNA expression, allowing transient rather than continuous high-level expression [8]. | Inducible systems prevent constant, high-level burden on the miRNA machinery and allow you to induce knockdown only during the experimental window, minimizing long-term saturation effects. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Immune Activation by dsRNA

Purpose: To determine if your RNAi trigger is activating the innate immune response. Key Materials: Cells, transfection reagent, synthetic siRNA/shRNA (test and control), TRIzol, qRT-PCR reagents.

- Treat Cells: Divide cells into three groups:

- Test Group: Transfected with your target siRNA/shRNA.

- Positive Control: Transfected with a known immunostimulatory RNA (e.g., in vitro transcribed ppp-dsRNA).

- Negative Control: Transfected with a non-immunostimulatory RNA (e.g., cap1-modified dsRNA or a commercial non-targeting control).

- Incubate: Incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Harvest RNA: Extract total RNA using TRIzol.

- Analyze by qRT-PCR: Synthesize cDNA and perform qRT-PCR for interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) such as OAS1 and IFIT1. Use housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, HPRT1) for normalization.

- Interpretation: A significant upregulation of ISGs in the test group compared to the negative control indicates immune activation. The positive control should show a strong response, while the negative control should not.

Protocol 2: Testing for Saturation of the miRNA Pathway

Purpose: To assess if your RNAi experiment is disrupting endogenous microRNA function. Key Materials: Cells, RNAi expression vector, control vector, reagents for RNA isolation and qRT-PCR, miRNA-specific assays.

- Establish Stable Cell Lines: Create cell lines stably expressing your shRNA (test) or a non-targeting control shRNA. Use inducible systems if possible.

- Extract RNA: Harvest total RNA, including the small RNA fraction, from both cell lines.

- Quantify Mature miRNAs: Using stem-loop RT-qPCR or similar specific assays, measure the levels of 2-3 highly expressed endogenous miRNAs (e.g., let-7a, miR-16).

- Quantify Primary miRNA Transcripts: Using standard qRT-PCR with primers flanking the Drosha processing site, measure the levels of the primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcripts for the same miRNAs.

- Interpretation: A significant decrease in the levels of mature miRNAs in the test group, without a corresponding decrease in their primary transcripts, is a classic signature of saturation. It indicates that the precursor miRNAs are being produced but their processing into mature forms is impaired due to competition with the experimental shRNA [16].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

dsRNA Innate Immune Recognition Pathway

The diagram below illustrates how different features of dsRNA activate distinct branches of the innate immune response.

RNAi Saturation of Endogenous miRNA Machinery

This diagram shows how high levels of exogenous shRNA can compete with and disrupt the normal biogenesis of endogenous miRNAs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their specific roles in mitigating the off-target effects discussed in this guide.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Cap1-modified dsRNA | An in vitro transcribed dsRNA with a 5' cap containing a 2'-O-methyl group on the first transcribed nucleotide [15]. | Effectively evades recognition by the RIG-I sensor, preventing the onset of dsRNA-induced cellular inflammation and interferon production [15]. |

| Chemically Modified siRNAs | siRNAs incorporating chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) in the sugar-phosphate backbone [3]. | Increases nuclease stability and can reduce immune activation. Some modifications also help to minimize seed-mediated off-target effects [3]. |

| miRNA-Embedded shRNA Vectors | Vector systems (e.g., Multi-miR) where the shRNA is expressed within the context of a natural microRNA backbone [20]. | Harnesses the cell's optimized miRNA biogenesis pathway for efficient processing, reducing competition and saturation of Exportin-5 and Dicer [20]. |

| Inducible shRNA Systems | shRNA expression systems (e.g., tetracycline/doxycycline-inducible) that allow precise temporal control over shRNA production [8]. | Enables transient knockdown, preventing long-term saturation of the RNAi machinery and allowing the study of essential genes whose permanent knockout would be lethal [8]. |

| Exportin-5 Expression Plasmid | A plasmid for co-expressing the Exportin-5 protein [16]. | Can be used as a diagnostic tool; if co-expression improves shRNA efficacy or reduces toxicity, it confirms that Exportin-5 was a saturated, limiting factor in the experiment [16]. |

FAQ: Understanding and Classifying RNAi Off-Target Effects

What are the main categories of RNAi off-target effects?

RNAi off-target effects are broadly classified into two categories based on their mechanism:

- Specific Off-Target Effects: These occur when the small interfering RNA (siRNA) or double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) exhibits partial complementarity to non-target mRNAs, leading to their degradation or translational repression. This is a sequence-dependent phenomenon [21] [22] [23].

- Non-Specific Off-Target Effects: These are sequence-independent effects triggered by the RNAi machinery or the dsRNA molecule itself. They include the activation of the innate immune response (e.g., interferon response), competition between siRNA and endogenous microRNAs (miRNAs) for the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), and saturation of the endogenous RNAi pathway [22] [23].

What sequence features determine specific off-target effects?

Specific off-target effects are primarily governed by the degree of sequence complementarity between the siRNA guide strand and non-target mRNAs. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research on dsRNA triggers, which are highly relevant for pest control and functional genomics in insects [22]:

| Feature | Description | Impact on Off-Target Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Sequence Identity | The percentage of identical nucleotides between the dsRNA and a non-target gene over the entire length. | dsRNAs with >80% sequence identity to a non-target gene can trigger significant off-target knockdown [22]. |

| Contiguous Perfect Match | A stretch of perfectly matched bases between the siRNA (derived from dsRNA) and an off-target mRNA. | A segment of ≥16 bp of perfectly matched sequence is sufficient to trigger RNAi of the off-target gene [22]. |

| Almost Perfect Match with Mismatches | A long stretch of sequence with scarcely distributed mismatches. | A segment of >26 bp with one or two mismatches can trigger off-target effects. Single mismatches inserted between ≥5 bp matching segments, or mismatched couplets inserted between ≥8 bp matching segments, also pose a risk [22]. |

| Seed Region Complementarity | Nucleotides 2-8 at the 5' end of the siRNA guide strand. | Perfect complementarity in this region can lead to miRNA-like translational repression of off-target mRNAs, even without full sequence match [22] [23]. |

How can I minimize immune-related non-specific off-target effects?

Non-specific effects, such as immune activation, are often dose-dependent and more prevalent in certain organisms [22]. In vertebrates, dsRNA longer than 30 bp can trigger an interferon response [22]. To minimize this:

- Optimize Dosage: Use the lowest effective concentration of dsRNA/siRNA to reduce the risk of saturating the RNAi machinery or triggering immune sensors [22] [23].

- Consider Delivery Method: Direct application of dsRNA (e.g., SIGS) may present different risks compared to endogenous expression in GM plants (HIGS) [21] [24].

- Utilize Bioinformatic Tools: Tools like dsRIP (Designer for RNA Interference-based Pest Management) are being developed to help design optimal dsRNA sequences that maximize efficacy while minimizing risks to non-target organisms [25].

Why do some target genes show different susceptibility to RNAi in the same organism?

Genes are not equivalent targets for RNAi. The natural RNA metabolism of a target gene can influence its susceptibility. Research in C. elegans has shown that an intersecting network of RNAi regulators (e.g., MUT-16, RDE-10, NRDE-3) exists. Some genes require all regulators for efficient silencing, while others can be silenced even if one regulator is missing. This suggests that the cellular context and regulation of the target gene itself contribute to the RNAi outcome [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Off-Target Effects

Problem: Observed Phenotype Does Not Match Expected Knockdown of Target Gene

This is a classic symptom of potential off-target effects. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnose the issue.

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Validation

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Bioinformatic Risk Assessment

This protocol is a prerequisite before conducting experiments to predict potential specific off-target effects [21] [22].

- Sequence Input: Obtain the full sequence of your dsRNA or siRNA trigger.

- Database Selection: Use a high-quality, annotated transcriptome or genome of the experimental organism. If using a model organism, a reference genome is ideal. For non-model organisms, a de novo assembled transcriptome may be used, acknowledging potential limitations [21].

- Alignment and Filtering:

- Use a local BLAST tool (e.g., BLASTn) to align the trigger sequence against the selected database.

- Apply filters to identify potential off-target candidates:

- Overall identity >80% over the entire length.

- Presence of contiguous perfect matches ≥16 bp.

- Presence of >26 bp segments with ≤2 mismatches.

- Manual Inspection: Manually inspect the top hits from the BLAST results to confirm the location and context of the matched sequences.

Protocol 2: Untargeted Transcriptomics for Off-Target Detection

This experimental protocol is used to empirically detect off-target effects by profiling global gene expression changes after RNAi treatment [21] [24].

- Experimental Design:

- Groups: Include a treatment group (dsRNA/siRNA) and a appropriate control group (scrambled RNA or buffer).

- Replicates: Use a minimum of three biological replicates per group to ensure statistical power.

- Sample Collection: Collect tissue or cells at a time point post-treatment that is relevant to the phenotype being studied.

- RNA Extraction & Sequencing:

- Extract total RNA using a method that preserves small RNAs (if interested in miRNA competition).

- Prepare RNA-seq libraries. For a comprehensive view, consider both standard mRNA-seq and small RNA-seq.

- Sequence the libraries on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Map sequencing reads to the reference genome/transcriptome.

- Perform differential gene expression analysis (e.g., using DESeq2 or edgeR).

- Identify Off-Targets: Look for significantly downregulated genes. Cross-reference these genes with the list of predicted off-target candidates from Protocol 1.

- Pathway Analysis: Use Gene Ontology (GO) or Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis to identify if downregulated genes are enriched in specific pathways, which may indicate a non-specific immune or stress response.

Visualization of the RNAi Pathway and Off-Target Mechanisms

The diagram below illustrates the core RNAi mechanism and points where specific and non-specific off-target effects can occur.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for studying and mitigating RNAi off-target effects.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Off-Target Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Long dsRNA (>200 bp) | The primary trigger for RNAi in many invertebrate and plant systems; processed into a pool of siRNAs [25] [26]. | The length increases the potential for generating multiple siRNAs with different off-target potentials. Design should follow rules on sequence identity and contiguous matches [22]. |

| Synthetic siRNA (21-22 nt) | Allows for precise targeting with a defined sequence; commonly used in mammalian systems [23]. | Enables chemical modification (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) to reduce immune activation and improve stability. The seed sequence should be carefully evaluated [23]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools (e.g., dsRIP) | Web-based platforms for designing optimized dsRNA/siRNA sequences [25]. | Algorithms can predict highly efficient siRNA strands within a dsRNA based on features like thermodynamic asymmetry and GC content, and identify potential off-targets in non-target species [25]. |

| Dicer/DCR-1 Mutants | Genetic tools to dissect the steps in the RNAi pathway [26]. | Used to confirm that observed effects are dependent on the canonical RNAi pathway. |

| RISC Component Mutants (e.g., RDE-1, Ago2) | Used to validate on-target engagement and understand mechanisms of off-target silencing [26] [23]. | Loss of function can abolish RNAi. Different Argonautes have specialized roles (e.g., NRDE-3 in nuclear silencing) [26]. |

| Transcriptomics Kits (RNA-seq) | For genome-wide experimental detection of off-target mRNA degradation [21] [24]. | Essential for unbiased discovery of both specific and non-specific off-target effects. Requires a high-quality reference genome. |

Your Troubleshooting Guide to Mitigating RNAi Off-Target Effects

This guide helps you identify and troubleshoot the primary causes of off-target effects in RNAi experiments, which can lead to misleading data and false conclusions.

| Troubleshooting Guide | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Key Controls to Implement |

| Sequence-Dependent Off-Targets | siRNA guide strand behaving like a microRNA, binding to and repressing transcripts with partial complementarity, especially in the "seed" region (nucleotides 2-8) [3] [2]. | - Bioinformatic Design: Use rigorous in silico tools to screen for complementarity to off-target transcripts, especially in the seed region [27] [25].- Chemical Modifications: Utilize siRNAs with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) to reduce seed-mediated off-targeting [3].- Pooled siRNAs: Use a pool of several siRNAs targeting the same gene at lower concentrations; off-target effects are not synergistic while on-target effects are [3] [28]. | |

| Saturation of Endogenous RNAi Machinery | High concentrations of transfected siRNA can overwhelm the cellular RNAi pathway, disrupting natural microRNA regulation and causing phenotypic changes unrelated to your target [2]. | Titrate siRNA: Use the lowest effective siRNA concentration. For many lipid-mediated transfections, 10 nM is often sufficient, reducing off-targets while maintaining efficacy [28]. | |

| Activation of Innate Immune Response | Introduction of dsRNA can trigger interferon-activated pathways, leading to global changes in gene expression that are mistaken for specific RNAi effects [1]. | - Quality Control: Ensure siRNA is highly pure and free of long dsRNA contaminants [28].- Design: Avoid immunostimulatory sequences in your siRNA design.- Validation: Include controls to measure interferon response markers. | |

| Inaccurate Guide Strand Selection | The incorrect strand of the siRNA duplex (the passenger strand) is loaded into RISC, leading to the silencing of non-targeted genes [3] [25]. | Design for Thermodynamic Asymmetry: Design siRNAs so the antisense (guide) strand has a less stable 5' end than the passenger strand. This biases RISC loading towards the intended guide strand [3] [25]. |

Essential Protocols for Validation

Following these detailed methodologies is critical for confirming that your observed phenotypic effects are due to specific on-target silencing.

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Bioinformatic Analysis for Off-Target Prediction

This protocol is adapted from EFSA guidance for risk assessment of RNAi-based genetically modified plants and provides a conservative framework for predicting potential off-target transcripts in your experimental system [27].

- Step 1: Sequence Preparation. Compile the complete sequence of all 21-nucleotide small RNAs potentially processed from your dsRNA or siRNA trigger.

- Step 2: Transcriptome Alignment. Perform an in silico search against the most up-to-date transcriptome of your model organism. The search should use specific alignment parameters:

- No more than four mismatches in total (or three mismatches and one single-nucleotide gap).

- G:U wobble pairs count as half a mismatch.

- No mismatches or gaps at position 10 or 11 of the small RNA.

- No more than two mismatches in the first 12 nucleotides at the 5' end.

- A minimum free energy (MFE) ratio of the duplex to the perfect complement of greater than 0.75 [27].

- Step 3: Risk Assessment. Prioritize off-target transcripts with multiple potential binding sites for different small RNAs from your trigger. Analyze the established or predicted function of these off-target genes to assess potential impact on your experimental outcomes [27].

Protocol 2: Experimental Confirmation of On-Target Engagement

This protocol outlines a rescue experiment, which is considered the gold standard for validating the specificity of an RNAi-induced phenotype.

- Step 1: Design a Rescue Construct. Clone the cDNA of your target gene into an expression vector. Crucially, introduce silent mutations in the region targeted by the siRNA. These mutations should not change the amino acid sequence but should make the mRNA resistant to silencing by your specific siRNA [28].

- Step 2: Co-transfection. Co-transfect your cells with both the siRNA and the rescue plasmid expressing the modified, siRNA-resistant target mRNA [28].

- Step 3: Phenotypic Analysis. Monitor whether the expression of the modified mRNA rescues the phenotype caused by the siRNA alone.

- Step 4: Interpretation. A successful reversal of the phenotype strongly indicates that the observed effect was due to specific silencing of your intended target and not an off-target effect.

Visualizing the Pathways to Reliable and Unreliable Data

The diagrams below illustrate the intended RNAi mechanism versus the common routes to off-target effects that compromise data integrity.

Key Reagents for Robust RNAi Experiments

The following table details essential materials and controls required to conduct reliable RNAi experiments and effectively manage off-target risks.

| Research Reagent Solutions | |

|---|---|

| Reagent / Control | Function and Importance |

| Validated & Modified siRNAs | Use siRNAs with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) to reduce seed-based off-target effects and increase stability [3]. |

| Bioinformatic Design Tools | Software (e.g., DEQOR, siDirect, dsRIP) is essential for selecting target sequences with high predicted efficacy and low potential for off-target binding [25]. |

| Positive Control siRNA | A siRNA known to achieve high knockdown of a standard gene (e.g., GAPDH). Validates your transfection and experimental conditions are working [28]. |

| Negative Control siRNA | A non-targeting (scrambled) siRNA with no significant homology to the transcriptome. Serves as the baseline for distinguishing specific silencing from non-specific effects [28]. |

| Fluorescent Transfection Control | A fluorescently-labeled oligonucleotide (e.g., BLOCK-iT Fluorescent Oligo) used to visually confirm and quantify transfection efficiency under the microscope [28]. |

| siRNA-Rescue Construct | A plasmid expressing the target mRNA with silent mutations in the siRNA-binding site. Gold-standard control to confirm phenotype specificity [28]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the fundamental difference between an off-target effect and a false positive in an RNAi screen? An off-target effect is the molecular event where an siRNA inadvertently silences genes other than its intended target. A false positive is the experimental consequence: you observe a phenotypic change and incorrectly attribute it to the silencing of your target gene, when it was actually caused by an off-target effect.

Q: I have used multiple siRNAs against the same target gene and they all produce the same phenotype. Does this rule out off-target effects? While this is a strong indicator of an on-target effect, it does not provide absolute proof. It is possible (though less likely) that each individual siRNA has its own unique set of off-target genes that, through different pathways, converge on the same phenotype. The most rigorous validation is a rescue experiment with an siRNA-resistant construct [28].

Q: My negative control siRNA is causing unexpected cytotoxicity. What could be wrong? This often points to issues with the siRNA preparation or transfection. The culprit could be:

- Chemical Contamination: The siRNA may contain salts or solvents from the synthesis process.

- Immunostimulation: The negative control sequence itself, or contaminants in the preparation, may be activating the innate immune response [28].

- Transfection Toxicity: The concentration of the transfection reagent may be too high. Re-optimize the reagent:siRNA ratio and always include an untransfected cell control.

Q: Are there advantages to using CRISPR-based knockdown (CRISPRi) over RNAi for gene silencing? Yes. CRISPRi functions at the DNA level by blocking transcription, and its guide RNA typically requires a perfect sequence match for binding, leading to significantly fewer sequence-based off-target effects compared to RNAi [1]. For loss-of-function studies where permanent knockout is not desired, CRISPRi can be a more specific alternative. However, the optimal choice depends on your experimental goals, as RNAi's ability to achieve partial, transient knockdown can be advantageous for studying essential genes [1].

Proactive Design Strategies for Enhancing RNAi Specificity and Efficacy

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Algorithm Selection and Data Interpretation

Q: My pre-designed siRNA is not producing the expected knockdown. What are the first parameters I should check?

A: Begin by troubleshooting the siRNA sequence itself and your experimental setup.

- Check siRNA Sequence Efficiency: siRNA efficacy is highly sequence-dependent. Review the GC content (optimal range is often 30-50%) and the stability of the 5'-terminal seed region (preference for A/U bases) [29].

- Verify mRNA Level Knockdown: Use real-time PCR to check mRNA levels at approximately 48 hours post-transfection. Ensure your qRT-PCR assay target site is positioned within a reasonable distance from the siRNA cut site to avoid issues with alternative splice transcripts [19].

- Confirm Transfection Efficiency: Always run a positive control siRNA in parallel to demonstrate that the transfection reagents are working and the siRNA is being delivered correctly to the cells [19].

Q: A key gene I need to target has a highly homologous gene family. How can I minimize off-target effects in this scenario?

A: This requires a multi-pronged bioinformatic and experimental approach.

- Leverage Advanced Prediction Tools: Use modern algorithms that incorporate deep learning, as they can better capture the complex patterns of off-target binding, including the critical importance of the seed region [30].

- Prioritize Specific Target Sites: During the design phase, use software that ranks potential target sequences based on the number of similar sites in the genome. Select the guide with the fewest and most dissimilar off-target candidates [31].

- Validate with Amplicon-Seq: After designing your siRNA, perform amplicon-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) on the top predicted off-target sites to empirically assess and confirm editing levels [32].

Q: What is the recommended strategy for comprehensively identifying off-target sites for a novel therapeutic siRNA candidate?

A: Relying on a single method is insufficient. A robust strategy involves a combination of in silico and experimental techniques [32].

- In Silico Prediction: Use one or more bioinformatic tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder, CCTop) to generate an initial list of potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity [33] [30].

- Unbiased Experimental Discovery: Employ a genome-wide, unbiased assay such as GUIDE-seq or DISCOVER-seq to identify off-target sites that are actually cleaved in a cellular context, which accounts for factors like chromatin accessibility [33] [32].

- Targeted Quantification: Use the combined list from the above steps to perform deep amplicon sequencing, which serves as the gold standard for quantifying the frequency of off-target effects at these candidate loci [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Pitfalls

| Problem Area | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Knockdown Efficiency | Suboptimal siRNA sequence; Low transfection efficiency; Incorrect assessment timing. | Test multiple siRNAs to the same target; Use a validated positive control; Perform a time-course experiment (check at 24h, 48h, 72h) [19]. |

| High Cell Toxicity | Toxicity from the transfection reagent itself; Excessive siRNA concentration. | Run a transfection reagent-only control; Titrate down the siRNA concentration and test different cell densities [19]. |

| Inconsistent Results | Protein turnover rate masking mRNA knockdown; Degraded RNA. | Run a longer time course to assess protein-level knockdown; Check RNA quality post-isolation [19]. |

| Unexpected Phenotypes | Off-target effects silencing genes with similar sequences. | Use a more stringent siRNA design algorithm; Employ a high-fidelity Cas nuclease variant if using CRISPR; Validate findings with multiple independent siRNAs/guides [34] [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Off-Target Validation

Protocol: Candidate Site Validation via Amplicon Sequencing

This protocol is considered the gold standard for quantifying off-target editing frequency at sites identified through prediction or discovery methods [32].

Key Reagents:

- Primers: Design specific primers to amplify each candidate off-target locus (typically 200-300 bp amplicons).

- NGS Library Prep Kit: Use a high-fidelity polymerase and a compatible NGS library construction kit.

- Control DNA: Include a non-transfected/control sample to establish baseline sequencing noise.

Methodology:

- Design Primers: Design and validate PCR primers for all candidate off-target sites from your in silico prediction and genome-wide discovery assays.

- Extract Genomic DNA: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from your treated and control cells.

- Amplify Targets: Perform PCR amplification of each candidate locus from both test and control samples.

- Prepare NGS Libraries: Pool the amplicons, prepare sequencing libraries, and sequence on an NGS platform with sufficient depth (e.g., >100,000x coverage) to detect low-frequency events.

- Analyze Data: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., Inference of CRISPR Edits - ICE) to align sequences and quantify the percentage of indels at each site, comparing treated samples to the control baseline [34].

Protocol: Genome-Wide Off-Target Discovery with GUIDE-seq

GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by sequencing) is a cellular method that captures double-strand breaks (DSBs) in living cells, providing biologically relevant off-target data [33] [32].

Key Reagents:

- GUIDE-seq Oligo: A short, double-stranded, blunt-ended oligonucleotide that is incorporated into DSBs.

- Transfection Reagents: For co-delivery of the GUIDE-seq oligo with your CRISPR RNP or siRNA.

- NGS Library Prep & Sequencing Reagents.

Methodology:

- Co-transfect Cells: Co-deliver the programmable nuclease (e.g., Cas9/sgRNA) or siRNA and the GUIDE-seq oligo into your target cells.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries that will capture the genomic regions flanking the integrated GUIDE-seq oligo. Sequence these libraries.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use the dedicated GUIDE-seq software pipeline to map the sequenced tags back to the reference genome, identifying all sites of DSB formation [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Silencer Select siRNA | A pre-designed siRNA format guaranteed to silence target mRNA by ≥70% when two siRNAs to the same target are used, providing a reliable starting point [19]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered Cas9 proteins (e.g., HypaCas9, eSpCas9) with reduced tolerance for mismatches, significantly lowering off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity [34] [4]. |

| Chemically Modified gRNAs | Synthetic guide RNAs with modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl analogs) that increase stability and can reduce off-target editing [34]. |

| Positive Control siRNA | A critical control (e.g., targeting GAPDH) used to confirm that transfection reagents and conditions are working optimally in your specific cell type [19]. |

| Negative Control Probe (dapB) | A bacterial gene probe used in assays like RNAscope to confirm the specificity of signal and the absence of background staining [35]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Off-Target Analysis Decision Workflow

siRNA Design Parameters for Specificity

FAQs on RNAi Off-Target Effects

What are the primary sequence-based factors that cause RNAi off-target effects?

Off-target effects in RNAi experiments are primarily governed by two key sequence-based factors: the overall percentage of sequence identity between the dsRNA and non-target genes, and the presence of long stretches of perfectly or almost perfectly matched bases. Research shows that dsRNAs with >80% overall sequence identity to a non-target gene can efficiently trigger its knockdown [22]. Furthermore, the presence of even short perfectly matched segments within the dsRNA is a major driver of off-target effects; a contiguous match of ≥16 base pairs (bp) is sufficient to trigger RNAi, and a segment of >26 bp with just one or two mismatches can also cause significant off-target knockdown [22].

How do the rules for dsRNA off-target effects differ from those for siRNA?

While both dsRNA and siRNA can cause specific off-target effects through complementary base pairing, the assessment of risk can differ due to the processing of long dsRNA into multiple siRNAs. For siRNA, the seed region (nucleotides 2-8 of the guide strand) can mediate off-target effects, and as few as 11 contiguous complementary nucleotides can induce knockdown of off-target genes [22]. For dsRNA, which is more suitable for pest control applications, the risk assessment must account for the potential for any of the resulting siRNAs to have high complementarity to an off-target transcript. This makes the presence of long, highly complementary stretches within the parent dsRNA a critical factor [22].

Can a dsRNA with low overall identity still cause an off-target effect?

Yes, experimental evidence confirms that a dsRNA with low overall sequence identity can still cause significant off-target knockdown if it contains a long enough stretch of perfectly or nearly perfectly matched sequence. One study found that a dsRNA sharing only 53% overall identity with a target gene still caused 44.6% knockdown of the target mRNA because it possessed a 36 bp stretch of contiguous matching bases [22]. This underscores the critical importance of analyzing local sequence homology in addition to global percentage identity when designing dsRNAs.

Besides sequence factors, what other variables influence off-target risk?

Other factors include the expression level and renewal rate of the non-target gene's expression products [22]. Genes with lower expression levels may be less susceptible to observable knockdown in some contexts. Furthermore, the biological function of the gene and the dynamics of the cellular network it operates in can also play a role, as compensation effects from related genes can sometimes lead to the upregulation of non-target transcripts [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Phenotype or High Mortality in Control Groups

Potential Cause: Widespread off-target effects leading to the silencing of multiple essential genes beyond the intended target.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Check Sequence Specificity: Re-analyze your dsRNA sequence against the most current genome assembly for the target organism. Use the thresholds in Table 1 to check for potential off-target genes.

- Validate with qPCR: Measure the expression levels of the primary target gene and the top potential off-target genes (those with high overall identity or long contiguous matches). An unexpected knockdown of multiple genes confirms an off-target problem.

- Redesign dsRNA: Design a new dsRNA targeting a different region of your intended gene, ensuring it minimizes both overall sequence identity (aim for <80%) and eliminates long contiguous matches (≥16 bp) with all other genes.

Problem: Inconsistent Knockdown Efficiency Between Biological Replicates

Potential Cause: Variable off-target effects interacting with genetic or physiological differences between replicates.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Standardize Delivery: Ensure the concentration and delivery method (e.g., injection, feeding) of dsRNA are perfectly consistent across all replicates.

- Profile Gene Expression: Conduct a broader gene expression analysis (e.g., RNA-seq) on a subset of variable and consistent replicates. Look for correlated silencing of off-target genes in samples with atypical phenotypes.

- Use Multiple dsRNAs: If possible, use two or more distinct dsRNAs targeting the same gene. If they produce the same on-target phenotype without the inconsistencies, the original dsRNA was likely the source of the problem.

The following tables consolidate the key experimental findings on sequence parameters governing RNAi specificity.

Table 1: Thresholds for dsRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing

| Parameter | Threshold for Efficient Silencing | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Sequence Identity | >80% | Random mutagenesis of dsRNA against target genes in T. castaneum [22] |

| Perfectly Matched Contiguous Sequence | ≥16 bp | Mutational analysis and off-target evaluation [22] |

| Nearly Perfect Contiguous Sequence | >26 bp with one or two mismatches scarcely distributed | Single mismatches inserted between ≥5 bp matches; mismatched couplets between ≥8 bp matches [22] |

Table 2: Experimental Evidence of Off-Target Effects

| Target Gene | Off-Target Gene | Overall Identity | Key Contiguous Match Feature | Observed Knockdown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP6BQ6 | CYP6BK13 | 71% | 26 bp of perfectly matched sequence | Significant [22] |

| CYP6BQ6 | CYP6BK7 | 68% | 24 bp stretch with only two single mismatches | Significant [22] |

| CYP6BK13 | CYP6BK13 (via dsCYP6BK13-53) | 53% | 36 bp stretch of contiguous matching bases | 44.6% [22] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Silico Assessment of dsRNA Off-Target Risk

This protocol describes a bioinformatics workflow to predict the risk of off-target effects for a candidate dsRNA sequence before synthesis.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Candidate dsRNA Sequence: The proposed sequence for your experiment.

- Bioinformatics Software: Access to a local or web-based BLAST suite.

- Reference Genome: The annotated genome sequence for your target organism and for any critical non-target organisms (e.g., beneficial insects in a pest control context).

- Sequence Analysis Tool: Software capable of performing pairwise sequence alignments (e.g., EMBOSS needle, custom Python/Bioperl scripts).

II. Methodology

- Sequence Preparation: Format your candidate dsRNA sequence in FASTA format.

- BLAST Analysis: Perform a BLASTN search of the dsRNA sequence against the reference genome database. Use a low word size (e.g., 7) and disable the filter for low complexity regions to maximize sensitivity.

- Identify Potential Off-Targets: Compile a list of all genes with a BLAST hit meeting an initial E-value cutoff (e.g., < 10). This is your initial risk list.

- Calculate Global and Local Identity:

- For each gene on the risk list, perform a global pairwise alignment with the dsRNA to determine the overall percentage sequence identity.

- Flag any gene with >80% overall identity as high risk.

- Scan for Contiguous Matches:

- For each gene on the risk list, perform a local alignment or use a sliding window algorithm to identify the longest stretch of perfectly matched bases.

- Similarly, identify the longest stretch with one or two mismatches.

- Flag any gene containing a contiguous perfect match of ≥16 bp, or an almost perfect match of >26 bp with the mismatch pattern described in Table 1, as high risk.

- Final Risk Assessment: A candidate dsRNA should be considered specific only if it has no high-risk off-target genes based on the criteria in steps 4 and 5.

Protocol: Experimental Validation of Off-Target Knockdown

This protocol outlines how to experimentally confirm suspected off-target effects in a laboratory setting.

I. Materials and Reagents

- dsRNA: The candidate dsRNA and a negative control dsRNA (e.g., targeting GFP or a gene from a different organism).

- Experimental Organisms: The insects or cells used in your assay.

- RNA Extraction Kit: A standard kit for high-quality total RNA isolation.

- cDNA Synthesis Kit: A reverse transcription kit.

- qPCR Equipment and Reagents: SYBR Green or TaqMan master mix, and a real-time PCR system.

- Gene-Specific Primers: Validated qPCR primers for the intended target gene and for the potential off-target genes identified in the in silico assessment.

II. Methodology

- Treatment and Sampling: Treat experimental groups with the candidate dsRNA and the negative control dsRNA using your standard method (e.g., microinjection or feeding). Perform the treatment in at least three biological replicates.

- RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis: At an appropriate timepoint post-treatment (e.g., 24-72 hours), harvest tissue or cells and extract total RNA. Synthesize cDNA from equal amounts of RNA for each sample.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Perform qPCR reactions using primers for your target gene and the potential off-target genes.

- Include at least one stable reference gene for normalization.

- Use a standard relative quantification method (like the 2^(-ΔΔCq) method) to calculate the fold-change in gene expression in the treated group compared to the control group.

- Data Interpretation: A statistically significant reduction (e.g., >50%) in the mRNA level of a gene other than the primary target confirms an off-target effect. The results should correlate with your in silico predictions.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Decision Workflow for dsRNA Specificity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for RNAi Specificity Research

| Item | Function in Research | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Long dsRNA (200-500 bp) | The primary trigger for the RNAi pathway in insects. More effective than siRNA for many insect systems [22]. | Should be designed using the specificity rules outlined above. Can be synthesized in vitro. |

| Bioinformatics Software (BLAST) | To identify potential off-target genes by searching for sequences with high similarity to the dsRNA [22]. | A critical first step for any dsRNA-based experiment. Use sensitive parameters. |

| qPCR Primers & Reagents | To quantitatively measure the knockdown efficiency of both the target gene and potential off-target genes [22]. | Essential for experimental validation of specificity. Requires stable reference genes. |

| Reference Genome Assembly | A high-quality, annotated genome for the target organism is necessary for a comprehensive in silico off-target prediction [22]. | The quality of the genome directly impacts the reliability of off-target predictions. |

A significant challenge in RNA interference (RNAi) research and therapy is the phenomenon of off-target effects, where a small interfering RNA (siRNA) unintentionally silences genes other than its intended target. This occurs primarily through a mechanism that mimics microRNA (miRNA) activity: the siRNA guide strand can bind to partially complementary sequences, particularly in the 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) of off-target mRNAs [36]. The seed region (nucleotides 2-8 from the 5' end of the guide strand) is critically important for this unintended binding [37] [36]. Off-target effects can lead to misleading results in functional genomics studies and pose a substantial risk for therapeutic applications. Consequently, developing robust strategies to suppress off-target silencing is a central focus in advancing RNAi technology.

FAQs: Understanding 2'-O-Methyl Modifications

Q1: How does a 2'-O-methyl (2'-O-Me) ribosyl substitution specifically reduce off-target effects?

A 2'-O-methyl (2'-O-Me) modification involves adding a methyl group to the 2' hydroxyl group of the ribose sugar in an RNA nucleotide [38]. When placed at specific positions on the siRNA guide strand—most critically at position 2—this chemical alteration disrupts the stable binding between the siRNA seed region and off-target mRNAs that have only partial complementarity [37]. It functions by weakening the RNA-RNA interaction in the seed region, thereby preventing the silencing of these unintended transcripts. Importantly, because the binding to perfectly matched, on-target mRNAs is more stable, this modification does not significantly compromise the intended gene silencing effect [37].

Q2: What is the optimal position for incorporating a 2'-O-methyl modification to minimize off-targeting?

Research has demonstrated a sharp position dependence for the 2'-O-methyl modification. Introducing the modification at position 2 of the guide strand has the most potent effect in reducing off-target silencing [37]. While modifications at positions 1 and 2 together are also effective, modification of position 1 alone shows little benefit [37]. The high specificity for position 2 suggests a unique role for this nucleotide in the guide strand that is distinct from its simple base-pairing function.

Q3: Do 2'-O-methyl modifications affect the on-target potency of an siRNA?

When applied correctly, 2'-O-methyl modifications do not negatively impact the silencing of the intended, perfectly matched target. Studies have confirmed that siRNAs with a 2'-O-Me modification at position 2 of the guide strand maintain full on-target silencing efficacy across a wide range of concentrations [37].

Q4: How do 2'-O-methyl modifications compare to seed region mismatches for improving specificity?

While introducing mismatches in the seed region can also reduce off-target effects, this approach has a broader position dependence and a major drawback: it can create a new, non-native seed sequence. This new sequence may then silence a new set of off-target transcripts complementary to the mutated sequence [37]. In contrast, the 2'-O-methyl modification at position 2 suppresses silencing of the original off-target transcripts without inducing a new off-target signature, making it a superior strategy for enhancing siRNA specificity [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Persistent Off-Target Effects After Modification

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Incorrect Modification Placement The efficacy of the 2'-O-methyl modification is highly position-specific.

- Solution: Verify that the modification is placed on the guide (antisense) strand at position 2. Consider also modifying position 1 of the guide strand and positions 1 and 2 of the passenger (sense) strand to further reduce passenger strand activity [37].

Cause 2: High siRNA Concentration Even with modifications, excessively high siRNA concentrations can saturate the RNAi machinery and exacerbate residual off-target binding.

- Solution: Perform a dose-response curve. Use the lowest possible siRNA concentration that still achieves the desired level of on-target knockdown. Testing concentrations between 5 nM and 100 nM is generally recommended [19].

Cause 3: Inherently Promiscuous Seed Sequence Some seed sequences may have high complementarity to many transcripts.

- Solution: Redesign the siRNA. Use multiple siRNAs targeting the same gene to confirm that observed phenotypes are due to on-target effects. Employ computational tools (e.g., BLAST) to screen for homology with other genes during the design phase [36].

Problem: Poor On-Target Knockdown After Modification

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Over-modification Excessively modifying the guide strand, especially outside the seed region, can interfere with its loading into RISC or its ability to cleave the target mRNA.

Cause 2: Assay-Related Issues The problem may not lie with the modification itself but with the experimental setup for measuring knockdown.

- Solution: Check mRNA levels using a sensitive method like quantitative RT-PCR. Ensure the qRT-PCR assay target site is not too far from the siRNA cut site (>3,000 bases away) to avoid issues with alternative splicing. Always use a validated positive control siRNA to confirm transfection efficiency and assay functionality [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating the Reduction of Off-Target Effects Using Microarrays

This protocol is based on the seminal study that established the role of 2'-O-methyl modifications [37].

1. Design and Synthesis:

- Design the siRNA against your target of interest.

- Synthesize two versions: an unmodified siRNA and a modified siRNA with a 2'-O-methyl ribosyl substitution at position 2 of the guide strand. Ensure the 5'-end of the guide strand is phosphorylated.

- Recommended Control: Include a 2'-O-methyl modification at positions 1 and 2 of the sense strand to minimize its contribution to off-target silencing.

2. Transfection:

- Culture appropriate cells (e.g., HeLa cells).

- Transfect cells with both the modified and unmodified siRNA duplexes. A range of concentrations (e.g., 10-50 nM) is recommended to assess dose-dependency.

3. Gene Expression Analysis:

- Time Point: Harvest cells 48 hours post-transfection.

- Method: Isolate total RNA and analyze global gene expression using microarray technology.

- Comparison: Compare the expression profiles of cells treated with unmodified siRNA versus modified siRNA.

4. Data Interpretation:

- On-Target Efficacy: Confirm that silencing of the intended target mRNA is comparable between modified and unmodified siRNAs.

- Off-Target Reduction: Identify transcripts significantly down-regulated by the unmodified siRNA but not regulated (or regulated to a lesser extent) by the modified siRNA. The study by Jackson et al. showed that this modification can reduce silencing of approximately 80% of off-target transcripts, with the magnitude of their regulation reduced by an average of 66% [37].

Protocol 2: Confirming Reduction of Off-Target Effects at the Protein Level

1. siRNA Treatment:

- Perform a dose titration of both modified and unmodified siRNA, as described in Protocol 1.

2. Protein Measurement:

- Time Point: Harvest cells for protein analysis at 48-72 hours post-transfection (or later, depending on the protein's half-life).

- Method: Use Western blotting with commercial antibodies to measure levels of both the on-target protein and a selected off-target protein.

- Selection of Off-Target Protein: Choose a protein whose transcript was identified as an off-target in microarray data and shares seed region complementarity with the siRNA [37].

3. Data Analysis:

- Compare the potency and maximal extent of silencing for both the on-target and off-target proteins between the modified and unmodified siRNAs. The modification should specifically reduce the silencing of the off-target protein without affecting the on-target protein [37].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of 2'-O-Methyl Modification on siRNA Specificity

| Parameter | Unmodified siRNA | 2'-O-Me Modified siRNA | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-Target Silencing | Unaffected / Full efficacy | Unaffected / Full efficacy | MAPK14 siRNA; mRNA level [37] |

| Off-Target Transcripts Regulated | Baseline (100%) | Reduced by ~80% | 10 different siRNAs; microarray [37] |

| Magnitude of Off-Target Regulation | Baseline (100%) | Reduced by ~66% (average) | 10 different siRNAs; microarray [37] |

| Off-Target Protein Silencing | Potent silencing | Potent reduction in silencing | PIK3CB siRNA; YY1 protein level [37] |

| False-Positive Phenotypes | Observed (e.g., growth inhibition) | Significantly reduced | Functional cell-based assays [37] |

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Specific siRNA Design

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Role in Suppressing Off-Targets |

|---|---|---|

| 2'-O-Methyl (2'-O-Me) Modification | A common chemical modification that alters the ribose sugar of specific nucleotides [38]. | Weaken RISC binding to partially complementary mRNAs when placed in the seed region (esp. position 2) of the guide strand [37]. |

| Phosphorothioate (PS) Linkage | Replaces a non-bridging oxygen with sulfur in the phosphate backbone [38]. | Increases nuclease resistance and improves pharmacokinetics, allowing for lower effective doses which can reduce off-target exposure [38] [36]. |