Mastering EMSA: A Comprehensive Guide to Studying Nucleic Acid-Protein Interactions in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), a foundational technique for detecting nucleic acid-protein interactions crucial for understanding gene regulation, transcription, and drug development.

Mastering EMSA: A Comprehensive Guide to Studying Nucleic Acid-Protein Interactions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), a foundational technique for detecting nucleic acid-protein interactions crucial for understanding gene regulation, transcription, and drug development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, the content spans from core principles and historical development to detailed, optimized protocols and advanced applications. It systematically addresses common methodological challenges, offers robust troubleshooting strategies, and explores advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses with other binding assays. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical applications, this guide serves as an essential resource for reliably implementing EMSA in modern molecular biology and therapeutic discovery.

EMSA Fundamentals: Unraveling the Principles of Nucleic Acid-Protein Interactions

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), also known as a gel shift or gel retardation assay, is a fundamental technique used to study interactions between proteins and nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) [1] [2]. This method is pivotal for investigating gene regulation, particularly by transcription factors, and is extensively applied in molecular biology to confirm suspected interactions, determine binding affinities, and elucidate specific binding sequences [1] [3]. The core principle of EMSA hinges on a simple yet powerful biophysical phenomenon: when a protein binds to a nucleic acid probe, the resulting complex migrates more slowly than the free nucleic acid during non-denaturing gel electrophoresis due to increased molecular size and alterations in net charge [1] [2]. This observable reduction in electrophoretic mobility, or "shift," provides direct evidence of an interaction. The following sections detail the physical principles underpinning this shift, present quantitative data on influencing factors, and provide a modern, accessible protocol for researchers.

Core Biophysical Principles of Mobility Shifts

The mobility shift observed in an EMSA is not an artifact but a direct consequence of the physical changes inflicted upon the nucleic acid upon protein binding. The two primary factors governing this shift are the molecular size and the charge of the complex, both of which are altered upon formation of the protein-nucleic acid complex.

The Role of Molecular Size and Mass

The foundation of the EMSA is the sieving effect of the gel matrix. A polyacrylamide or agarose gel acts as a three-dimensional mesh through which molecules must travel. The migration rate of a molecule is inversely proportional to its mass and hydrodynamic volume [2] [4]. A naked, linear DNA or RNA fragment is relatively compact and can navigate the pores of the gel efficiently. When one or more proteins bind, the mass and physical dimensions of the complex increase substantially, hindering its progress through the gel. This results in the characteristic "shift" or "retardation" where the protein-bound nucleic acid is found closer to the gel's origin compared to the free probe [2]. This principle is robust enough to resolve complexes of different stoichiometries or conformations [2]. When working with large complexes or intrinsically disordered proteins (IDRs), which may require the binding of multiple protein units to produce a detectable shift, a significant molar excess of protein is often necessary to increase the complex's mass [4].

The Role of Molecular Charge

While size is a critical factor, the net charge of the complex plays an equally important role in determining electrophoretic mobility. Nucleic acids are highly negatively charged due to their phosphate-sugar backbones. During electrophoresis, this negative charge drives the molecule toward the positive anode. When a protein binds, it contributes its own net charge to the complex. The overall charge of the resulting complex depends on the isoelectric point (pI) and charge of the protein under the assay conditions. The binding of a positively charged protein (e.g., a transcription factor with a basic domain) partially neutralizes the negative charge of the nucleic acid, reducing the net charge density of the complex and contributing to its slower migration [5]. This electrostatic attraction is a significant driving force for many protein-nucleic acid interactions. In fact, a comprehensive analysis of 369 aptamer-protein pairs revealed a significant inverse correlation between a protein's isoelectric point (pI) and the dissociation constant (KD) of the complex, meaning that more positively charged proteins tend to form higher-affinity complexes with negatively charged nucleic acids [5]. Furthermore, the gel matrix provides a "caging" effect that helps stabilize the interaction complexes; even if components dissociate, their localized concentrations remain high, promoting prompt reassociation [2].

Table 1: Key Factors Affecting Electrophoretic Mobility in EMSA

| Factor | Effect on Nucleic Acid Probe | Effect on Protein-Nucleic Acid Complex | Net Effect on Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mass/Size | Low mass, small hydrodynamic volume. | Increased mass and hydrodynamic volume. | Decreased mobility (shift/retardation). |

| Net Charge | High negative charge. | Reduced negative charge (if protein is basic). | Decreased mobility. |

| Complex Stoichiometry | Single species. | Larger complexes with more protein subunits. | Progressively decreased mobility. |

| Gel Matrix Pore Size | Faster migration in lower percentage gels. | Larger complexes require gels with larger pores (e.g., lower % acrylamide or agarose). | Must be optimized for the complex of interest. |

Quantitative Data on Molecular Interactions

Understanding the quantitative aspects of these interactions is crucial for experimental design and data interpretation. The following table summarizes key parameters from recent research that influence complex formation and stability.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters Affecting Complex Formation and Detection

| Parameter | Typical Range or Value | Impact on EMSA | Supporting Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Charge (pI) | pI > 7.4 for positive net charge at physiological pH. | Positively charged proteins (high pI) show stronger binding and easier detection due to electrostatic attraction with nucleic acids [5]. | Analysis of 369 aptamer-protein pairs showed a significant inverse correlation between protein pI and KD [5]. |

| Protein:DNA Molar Ratio | Wide range (e.g., 50:1 to 12,500:1 for IDRs); typically titrated. | High molar excess of protein may be needed to shift DNA, especially for low-affinity binders or IDRs [4]. | For IDRs, a high molar excess (e.g., 0.01–2.5 μM IDR to 0.2 nM DNA) is recommended to promote multiple binding events and a detectable mass change [4]. |

| Salt Stability (CSC) | Varies; e.g., 99.3 mM NaCl for R4/DNA8 vs. 215.9 mM for R4/RNA8. | Indicates complex robustness; higher CSC values correspond to more stable complexes resistant to dissociation by ionic strength. | RNA-peptide coacervates show ~2.2x greater salt stability than DNA-peptide analogues, suggesting stronger interactions [6]. |

| Thermal Stability | Varies; e.g., dissolution at ≈45°C for R4/DNA8 vs. ≈60°C for R4/RNA8. | Indicates complex stability under temperature stress; higher dissolution temperatures suggest more stable interactions. | RNA-peptide coacervates demonstrate exceptional thermal stability compared to DNA-based ones [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Fluorescent EMSA

This protocol provides a detailed method for performing a non-radioactive EMSA using fluorescently labeled probes, adapted from modern approaches [7] [8]. It uses the PPF-EMSA (Protein from Plants Fluorescent EMSA) and FluoTag-EMSA principles, which can be adapted for proteins from various sources.

Reagent Preparation

- DNA Probe Labeling:

- Design: Synthesize complementary oligonucleotides containing the specific protein-binding sequence. For a double-stranded probe, design two complementary strands.

- Labeling (Cy3): Order one oligonucleotide with a Cy3 fluorophore conjugated to its 5' end. Alternatively, for the FluoTag method, add a specific short sequence tag to the 3' end of your RNA probe and hybridize it post-synthesis to a complementary DNA oligonucleotide carrying a fluorophore like Cy5 or IRDye 800 [8].

- Annealing: Combine the labeled strand and its unlabeled complementary strand in an equimolar ratio in annealing buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 50 mM KCl, pH 9.0). Heat the mixture to 98°C for 2 minutes and then allow it to cool slowly to room temperature over 30-60 minutes to form double-stranded probes [7].

- Protein Extraction and Purification:

- Source: The protein of interest can be a purified recombinant protein, an in vitro transcription/translation product, or a protein isolated from a native source (e.g., plant or mammalian nuclear extracts) [7] [2].

- PPF-EMSA Method: For proteins from host plants, use a transient transformation system to express the protein fused to an epitope tag (e.g., FLAG). Isolate the protein using immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody [7]. This ensures the protein is in a natural state with relevant post-translational modifications.

- Binding Buffer (2X):

- Competitor DNA:

- Non-specific Competitor: Use poly(dI•dC) or sonicated salmon sperm DNA to adsorb proteins that bind non-specifically to any DNA sequence.

- Specific Competitor: Use an unlabeled, double-stranded oligonucleotide identical to the probe sequence to verify binding specificity.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Binding Reaction Setup:

- In a low-adhesion microcentrifuge tube, assemble the following components in order:

- Nuclease-free water (to a final volume of 20 μL)

- 2 μL of 10X non-specific competitor DNA (e.g., poly(dI•dC))

- 2 μg of protein extract (or a molar titration of purified protein)

- 10 μL of 2X Binding Buffer

- Critical Note: The order of addition is crucial. The non-specific competitor must be added before the labeled probe to quench non-specific binding sites [2].

- Incubate the mixture for 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

- Add 1-2 μL of the labeled DNA probe (10-50 fmol) to each reaction. Mix gently.

- Specificity Control: For competition assays, add a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled specific competitor to the reaction before adding the labeled probe.

- Incubate the binding reaction for 20-30 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- In a low-adhesion microcentrifuge tube, assemble the following components in order:

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Prepare a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-6%) or an agarose gel (e.g., 0.8-1.2% for larger complexes) in 0.5X TBE or TAE buffer. Pre-run the gel for 30-60 minutes at the recommended voltage (e.g., 80-100 V) in a cold room or with a cooling apparatus to maintain a constant temperature.

- After the binding incubation, add 2-3 μL of a non-denaturing loading dye (e.g., 30% glycerol with trace amounts of xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue) to each reaction. Do not use dyes containing SDS.

- Load the samples onto the pre-run gel. Run the gel at 80-100 V, keeping the apparatus in the dark or covered with foil to protect the fluorophore.

Visualization and Analysis:

- Following electrophoresis, carefully transfer the gel to a flatbed fluorescence scanner.

- Scan the gel using the appropriate laser and filter settings for your fluorophore (e.g., Cy3: excitation ~550 nm, emission ~570 nm).

- The free DNA probe will appear as a fast-migrating band. Protein-DNA complexes will be visualized as slower-migrating bands above the free probe.

- Quantify the band intensities using software like Image Studio (LI-COR) or ImageJ to calculate the fraction of bound vs. free DNA, which can be used for determining dissociation constants (KD) [9] [4].

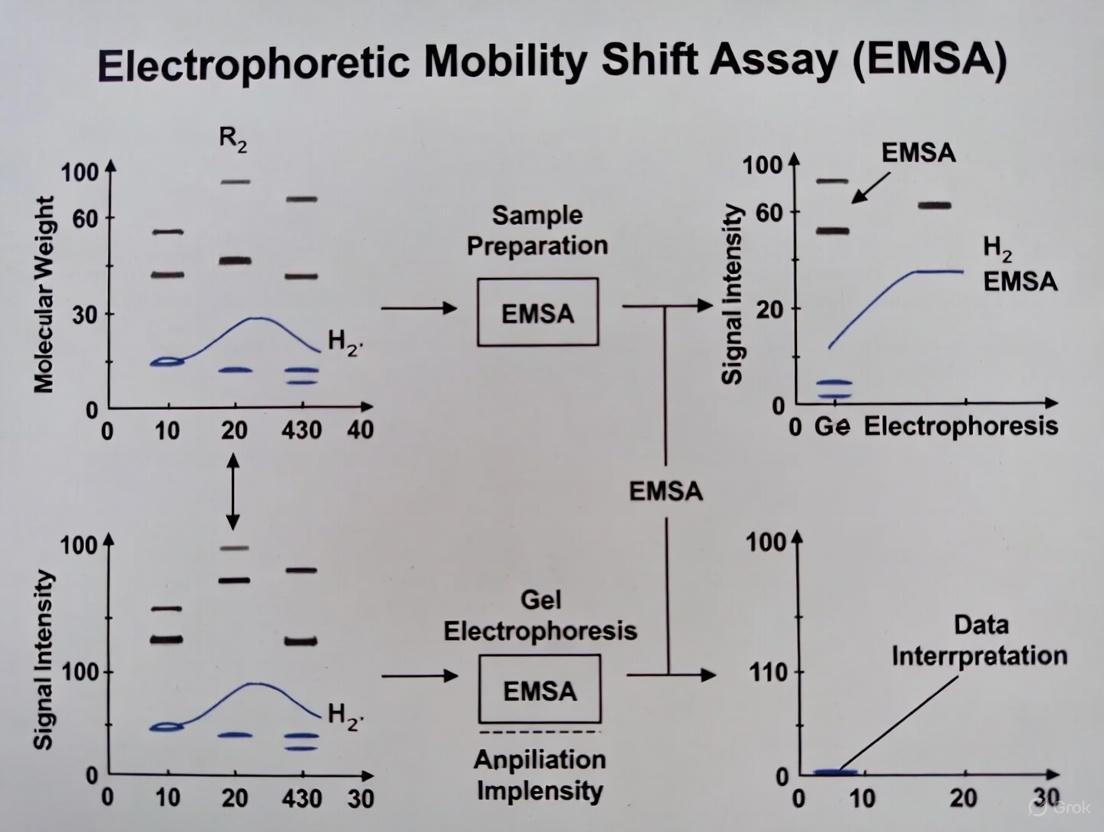

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for a fluorescent EMSA, culminating in the core biophysical principle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful EMSA requires careful selection of reagents. The table below lists key solutions and materials essential for the protocol.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Fluorescent EMSA

| Research Reagent | Function / Rationale | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled DNA Probe | The detectable target for protein binding. | Cy3-labeled dsDNA oligo or FluoTag-labeled RNA for sensitive, non-radioactive detection [7] [8]. |

| Protein Sample | The DNA-binding factor. | Recombinant protein, in vitro expressed protein, or native protein from nuclear extracts or immunoprecipitation (e.g., PPF-EMSA) [7] [2]. |

| Non-specific Competitor | Blocks non-specific protein-DNA interactions. | Poly(dI•dC) or sonicated salmon sperm DNA; must be added before the labeled probe [2]. |

| Specific Competitor | Validates binding specificity. | A 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe sequence; competes for binding and should abolish the shifted band [2]. |

| Binding Buffer | Provides optimal conditions for complex formation. | Typically contains salts (KCl, MgCl₂), buffering agents (HEPES), reducing agents (DTT), and stabilizers (glycerol, BSA) [4]. |

| Non-Denaturing Gel Matrix | Resolves free probe from protein-bound complexes. | Polyacrylamide (for high resolution of small complexes) or Agarose (for large complexes or IDRs) [4]. |

| Fluorescence Scanner | Detects the fluorescently labeled probe and complex. | A scanner with appropriate lasers/filters for Cy3, Cy5, or IRDye dyes. |

Troubleshooting and Advanced Applications

Common Challenges and Solutions

- No Shift Observed: Ensure protein is active and functional; optimize binding buffer components (e.g., divalent cations, pH); increase protein concentration; check for protease degradation.

- High Background or Smearing: Increase the concentration of non-specific competitor; titrate the labeled probe to use less; ensure the gel is run at the proper temperature (cold room).

- Complex Stuck in Well: The complex may be too large; use a lower percentage gel or agarose gel; add mild detergents like NP-40 to the binding reaction to prevent aggregation [4].

Advanced Applications

The basic EMSA principle has been adapted for various sophisticated applications. The super-shift assay involves adding a specific antibody to the binding reaction. If the antibody binds to the protein in the complex, it creates an even larger "super-shifted" complex with further reduced mobility, confirming the protein's identity [7]. EMSA can also be used to study protein-RNA interactions, which are crucial for post-transcriptional gene regulation [8]. Furthermore, novel readout methods like chemiluminescence using digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes offer high sensitivity without radioactivity [9].

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), also known as the gel retardation assay, stands as a cornerstone technique in molecular biology for detecting interactions between proteins and nucleic acids. The modern EMSA was formally established in 1981 through independent work by Fried and Crothers [10] and Garner and Revzin [11], who systematically developed the method for quantifying protein-DNA interactions. This protocol provided a robust, sensitive means to study binding equilibria and kinetics, filling a critical methodological gap in the study of gene regulation. The core principle of EMSA is elegantly simple: when a protein binds to a nucleic acid (DNA or RNA), the resulting complex migrates more slowly than the free nucleic acid during non-denaturing gel electrophoresis, resulting in a measurable "mobility shift" [2]. The technique's ability to resolve complexes of different stoichiometries or conformations, using everything from crude cellular extracts to purified proteins, has secured its enduring popularity for over four decades [10] [2].

Historical Development and Technological Evolution

The Foundational Era (1980s)

The initial adoption of EMSA in the 1980s was driven by its simplicity and the qualitative clarity it provided. Early applications focused on identifying sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins, such as transcription factors, in complex mixtures. A landmark in the technique's history was its application to the E. coli lactose operon system, which helped solidify its quantitative potential for determining binding affinities and stoichiometries [11]. During this period, the technology relied almost exclusively on radiolabeling with ³²P for detection, offering high sensitivity but introducing significant safety and regulatory concerns [7] [2]. While the core methodology was established in 1981, its roots can be traced back to earlier observations of electromagnetism and interference, with the term EMI (Electromagnetic Interference) being formally recognized by the International Electrotechnical Commission as early as 1933 [12].

Refinement and Expansion (1990s - Early 2000s)

The subsequent decades witnessed significant refinements aimed at overcoming the technique's limitations. Researchers developed a multitude of EMSA variants to address specific experimental questions, as detailed in Table 1. A major push during this era was to find non-radioactive detection methods. The development of probes labeled with haptens like biotin and digoxigenin, detected through chemiluminescence, provided a safer and more accessible alternative without sacrificing sensitivity [2]. Concurrently, the "supershift" assay, which uses antibodies specific to the DNA-binding protein to further retard the complex's mobility, became a standard for verifying the identity of proteins in a complex [10].

Modern Innovations and Applications (2010s - Present)

The modern era of EMSA is characterized by a focus on biological relevance, quantitative precision, and technological integration. A key innovation is the Protein from Plants Fluorescent EMSA (PPF-EMSA), developed to more accurately reflect in vivo conditions. This method involves transiently expressing proteins in host plants, allowing them to fold naturally and acquire essential post-translational modifications (PTMs), which are often missing in proteins expressed in prokaryotic systems like E. coli [7]. This advancement ensures that the observed DNA-binding activity more closely mirrors the true biological function of the protein.

Furthermore, the push for precise quantification has led to sophisticated software solutions, such as the 'Densitometric Image Analysis Software'. This tool addresses the non-linearity of autoradiographic films and can account for experimental errors, enabling the determination of stepwise equilibrium constants with uncertainties as low as ~20%, a significant improvement over the earlier factor of ~2 [13]. The adoption of fluorescent dyes like Cy3 and Cy5 for direct in-gel detection has also gained traction, reducing assay time and cost while allowing real-time visualization of DNA-protein interactions during electrophoresis [7].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in EMSA Development

| Time Period | Key Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1981 | Precursor techniques [11] | Laid groundwork for separation of macromolecular complexes. |

| 1981 | Formal establishment of EMSA by Fried & Crothers and Garner & Revzin [10] [11] | Provided a standard, quantitative method for studying protein-nucleic acid interactions. |

| 1980s-1990s | Proliferation of variants (supershift, competition, reverse EMSA) [10] | Expanded applications to kinetics, stoichiometry, and complex protein identification. |

| 1990s-2000s | Non-radioactive detection (biotin, digoxigenin) [2] | Improved safety and accessibility; enabled chemiluminescent detection. |

| 2000s-2010s | Fluorescent EMSA (Cy3, Cy5) [7] | Enabled direct, real-time in-gel detection, simplifying protocol. |

| 2010s-Present | PPF-EMSA (protein isolation from host plants) [7] | Ensured native protein folding and PTMs for biologically relevant results. |

| 2010s-Present | Advanced densitometric software analysis [13] | Enabled highly accurate quantification of binding constants from EMSA data. |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Core EMSA Protocol

The following protocol outlines the standard steps for a modern, non-radioactive EMSA, adaptable for either chemiluminescent or fluorescent detection.

A. Probe Preparation and Labeling

- Probe Design: For defined binding sites, synthesize complementary oligonucleotides (20-50 bp) and anneal them to form a double-stranded probe. For complex multi-protein binding, use longer fragments (100-500 bp) generated by PCR or restriction digestion [2].

- Labeling: Choose a detection method based on equipment and sensitivity needs.

- Biotin/DIG Labeling: Incorporate a hapten-labeled nucleotide during PCR or use end-labeling kits. Probes are later detected by chemiluminescence after gel transfer to a membrane [2].

- Fluorescent Labeling: Synthesize primers with a 5' fluorescent dye (e.g., Cy3) and use them to generate your probe via PCR. The labeled probe can be detected directly in the gel [7].

B. Protein Sample Preparation

- Source Selection: The protein source depends on the experimental question.

- Prokaryotic Expression: Suitable for initial characterization but may lack PTMs [7].

- PPF-EMSA Method: For host-specific studies, clone the gene of interest into a transient expression vector with an epitope tag (e.g., FLAG). Express the protein in plant tissues (e.g., Betula platyphylla, Arabidopsis thaliana) and purify it using immunoprecipitation with an antibody against the tag [7]. This yields natively folded, post-translationally modified protein.

C. Binding Reaction

- Master Mix: Assemble binding reactions on ice. A typical 20 µL reaction may contain:

- Binding Buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 50 mM KCl, pH 9.0 [7]. Note: Buffer composition (ionic strength, pH, divalent cations) is protein-specific and must be optimized.

- Non-specific Competitor: 1 µg of poly(dI•dC) or sonicated salmon sperm DNA. Crucially, add this to the protein first to block non-specific binding [2].

- Specific Competitor (for specificity control): A 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled identical probe. Add this after the non-specific competitor but before the labeled probe [2].

- Labeled Probe: Typically 0.1-10 nM. Add last to the mixture.

- Protein Extract: Amount is determined empirically via titration.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at room temperature or a specified temperature for 20-30 minutes to allow complex formation.

D. Electrophoresis and Detection

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a non-denaturing polyacrylamide (typically 4-10%) or agarose gel in a low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., 0.5x TBE) pre-chilled to 4-10°C.

- Loading and Running: Load the binding reactions without denaturing dyes (or with minimal, non-ionic dyes like bromophenol blue). Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100 V), keeping the apparatus cool to stabilize complexes.

- Detection:

- Chemiluminescent: Transfer nucleic acids to a positively charged nylon membrane via electroblotting. Detect the biotin/DIG-labeled probe using streptavidin- or antibody-conjugated enzymes and a chemiluminescent substrate [2].

- Fluorescent: Directly visualize the gel using a fluorescence scanner or imager equipped with the appropriate excitation/emission filters (e.g., 532 nm excitation for Cy3) [7].

Diagram 1: EMSA Experimental Workflow. The flowchart outlines the core steps of a modern EMSA, highlighting key parallel paths for protein preparation and detection methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for EMSA

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled DNA Probe | The detectable nucleic acid target for binding. | Can be radiolabeled, hapten-labeled (biotin), or fluorescently labeled (Cy3). Size (20-500 bp) depends on application. |

| Binding Buffer | Provides the chemical environment (pH, ions) for complex formation. | Must be optimized for each protein; may require Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, DTT, or glycerol. |

| Non-specific Competitor DNA | Absorbs non-sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins to reduce background. | Poly(dI•dC) or sonicated salmon sperm DNA. Must be added before the labeled probe [2]. |

| Specific Competitor DNA | Unlabeled identical probe used to confirm binding specificity. | A 200-fold molar excess should abolish or diminish the shifted band [2]. |

| Antibody (Supershift) | Binds to the protein in the complex, causing a further mobility shift. | Used to confirm the identity of the binding protein in the complex. |

| Non-denaturing Gel Matrix | Separates protein-nucleic acid complexes from free nucleic acid. | Typically polyacrylamide; the "caging" effect helps stabilize complexes during electrophoresis [2]. |

Current Applications and Data Analysis

EMSA remains a vital tool in both basic and applied research. Its applications extend beyond confirming simple protein-DNA binding to include:

- Determination of Binding Stoichiometry: Resolving complexes with different protein-to-DNA ratios within a single lane [10] [13].

- Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies: Measuring association and dissociation rate constants, as well as equilibrium binding constants [10] [11].

- Analysis of Cooperative Binding: Studying how the binding of one protein molecule influences the binding of subsequent molecules to adjacent sites on the DNA [13].

- Identification of Unknown Proteins: Using supershift assays or coupling with Western blotting and mass spectrometry to identify proteins in DNA-protein complexes [10].

For quantitative analysis, software like the 'Densitometric Image Analysis Software' is used to measure band intensities. The program corrects for the non-linear response of autoradiographic film and calculates a stepwise equilibrium constant (K) for each lane using the formula: K = [Protein-DNA Complex] / ([Free DNA] * [Free Protein]) [13]. By accounting for background noise, smearing, and technical errors, this software can reduce the inaccuracy of equilibrium constants to approximately 20%, enabling the generation of precise data for predictive models of genomic binding [13].

Table 3: Evolution of EMSA Detection Methods and Their Characteristics

| Detection Method | Era of Prominence | Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiolabeling (³²P) | 1980s - Present | Very High | High sensitivity; historical gold standard | Health hazards; regulatory disposal; short probe half-life |

| Chemiluminescence (Biotin/DIG) | 1990s - Present | High (comparable to ³²P) | Safe; cost-effective; stable probes | Requires membrane transfer; extra detection steps |

| Fluorescence (Cy3, Cy5) | 2000s - Present | Moderate to High | Real-time monitoring; no transfer; fast protocol | Requires specialized imaging equipment; can be less sensitive than chemiluminescence |

From its formal inception in 1981 to the present day, the Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay has demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability. Its evolution from a qualitative tool using radioactive probes to a quantitative, versatile technique employing fluorescent tags and sophisticated software mirrors broader trends in molecular biology. The development of methods like PPF-EMSA, which prioritizes biological context by using proteins from host organisms, ensures that EMSA will continue to provide physiologically relevant insights into gene regulation. As it continues to be integrated with other analytical techniques and adapted to new scientific questions, EMSA solidifies its status as an indispensable protocol for researchers exploring the fundamental interactions between proteins and nucleic acids.

The study of protein-nucleic acid interactions is fundamental to understanding critical cellular processes such as transcription, DNA replication, and repair. At the heart of characterizing these molecular interactions lies the concept of binding equilibrium—a dynamic state where the association and dissociation of a protein-nucleic acid complex occur at equal rates. The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), also known as a gel shift or gel retardation assay, serves as a core technology for detecting and quantifying these interactions by leveraging the principle that protein-bound nucleic acids migrate more slowly through a native gel than their free counterparts [10] [2]. This application note provides a detailed framework for applying EMSA to quantitatively analyze the binding equilibrium, complete with protocols, key reagents, and data interpretation guidelines.

Theoretical Foundations of Binding Equilibrium

The formation of a protein-nucleic acid complex can be represented by the simple equilibrium equation: P + NA ⇌ P-NA

Where P represents the protein, NA the nucleic acid, and P-NA the complex. The equilibrium association constant (K~a~) is defined as K~a~ = [P-NA] / [P][NA], providing a direct measure of binding affinity [10]. A higher K~a~ value indicates a tighter, more favorable interaction.

The molecular forces governing this equilibrium are diverse and include:

- Electrostatic Interactions: Attraction between charged amino acid residues and the negatively charged DNA phosphate backbone is a primary driver, often considered a long-range guiding force [14].

- Hydrogen Bonding: Networks of hydrogen bonds between protein side chains and nucleic acid bases can confer sequence specificity [14].

- Hydrophobic Effect and Van der Waals Forces: The burial of hydrophobic surfaces and close-range atomic interactions contribute significantly to the overall binding energy and complex stability [14].

- Stacking Interactions: In some complexes, aromatic amino acid residues can stack with nucleic acid bases, further stabilizing the structure [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Forces in Protein-Nucleic Acid Interactions

| Interaction Type | Key Features | Role in Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic | Long-range; protein positive charges with DNA phosphates | Low; provides general affinity for DNA |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Directional and geometry-dependent; with DNA bases | High; recognizes specific base sequences |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Releases ordered water molecules; buries apolar surfaces | Medium; contributes to overall stability |

| Stacking | π-orbital interactions between aromatic systems | Variable; can stabilize everted bases |

The EMSA Technique: Principles and Workflow

EMSA is a robust method that captures a "snapshot" of the binding equilibrium. The protein-nucleic acid complex, once formed, is resolved from the free nucleic acid via native polyacrylamide or agarose gel electrophoresis. The gel matrix itself provides a "caging effect" that helps stabilize transient complexes during the electrophoretic process [2].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and underlying equilibrium of a typical EMSA experiment:

The success of an EMSA depends on several key factors that influence complex stability and migration. These include buffer conditions (ionic strength, pH, divalent cations), temperature, and the concentration of competitors [10] [2]. The table below summarizes the ranges for critical binding parameters.

Table 2: Key Parameters for EMSA Binding Reactions

| Parameter | Typical Range | Purpose and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 0°C to 60°C [10] | Affects complex stability; often room temperature for 20-30 min [15] |

| pH | 4.0 to 9.5 [10] | Must be compatible with protein activity and complex formation |

| Monovalent Salt (KCl/NaCl) | 1 mM to 300 mM [10] | Lower salt generally stabilizes electrostatic interactions |

| Divalent Cations (Mg²⁺) | ≤ 20 mM [10] | Often essential for zinc-finger proteins and enzymatic activity [2] |

| Reducing Agents (DTT) | ≤ 10 mM [10] | Maintains cysteine residues in reduced state |

| Non-specific Competitor | Variable (e.g., poly(dI·dC)) [2] | Binds non-specific proteins to reduce background |

| Carriers (Glycerol, BSA) | Glycerol ≤ 2 M [10] | Aids gel loading; BSA can stabilize some proteins |

Detailed Protocol: Fluorescent EMSA

This protocol uses infrared or Cy3-labeled DNA probes, offering a safe and sensitive alternative to radioactive detection [15] [7] [16].

Reagent Preparation

- DNA Probe Design: Design a double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide (~20-50 bp) containing the specific protein binding site.

- Probe Labeling: Label the probe at one or both 5' ends with a fluorophore (e.g., IRDye 700, Cy3) [15] [7]. Using two labeled strands can significantly increase signal intensity [15].

- Probe Annealing: Combine equimolar amounts of complementary oligonucleotides in STE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). Heat to 100°C for 3-5 minutes and allow to cool slowly to room temperature in the dark [15] [16].

- Protein Source: Use purified recombinant protein or protein isolated from host organisms (e.g., via immunoprecipitation from transiently transformed plants) [7]. Host-isolated proteins offer native folding and post-translational modifications.

Gel Preparation

Prepare a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The following recipe makes ~40 mL for a mini-gel system:

- 5 mL of 40% polyacrylamide stock (29:1 acrylamide:bis)

- 2 mL of 1 M Tris, pH 7.5

- 7.6 mL of 1 M Glycine

- 160 μL of 0.5 M EDTA

- 26 mL of H₂O

- 200 μL of 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS)

- 30 μL of TEMED

Mix thoroughly and pour immediately. Allow 1-2 hours for complete polymerization [15]. Pre-cast TBE gels (e.g., 4-12%) are also suitable [15].

Binding Reaction

Set up a 20 μL reaction as follows for the NFκB model system [15]:

Table 3: Sample Binding Reaction Setup

| Component | Volume | Final Concentration/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 10X Binding Buffer | 2 μL | 100 mM Tris, 500 mM KCl, 10 mM DTT; pH 7.5 |

| Poly(dI·dC) (1 μg/μL) | 1 μL | Non-specific competitor DNA |

| 25 mM DTT / 2.5% Tween 20 | 2 μL | Stabilizes dye and improves quantification [15] |

| Nuclease-free Water | 13 μL | Adjusts final volume |

| IRDye 700-labeled Probe | 1 μL | ~20 fmol of labeled DNA target |

| Protein Extract/Protein | 1 μL | 5 μg of nuclear extract or purified protein |

Incubation: Mix components gently. The order of addition is critical. Add the non-specific competitor first with the protein, followed by the labeled probe. Incubate the reaction for 20-30 minutes at room temperature in the dark [15] [2].

Electrophoresis and Detection

- Add 1 μL of 10X native loading dye (e.g., LI-COR Orange) to the binding reaction. Avoid dyes like bromophenol blue, which interfere with fluorescence detection [15].

- Load the entire reaction onto the pre-run native gel.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of ~10 V/cm in 0.5X or 1X TBE/TGE buffer for approximately 30 minutes or until sufficient separation is achieved. Perform electrophoresis in the dark to prevent photobleaching [15].

- Image the gel directly in the glass plates or after carefully transferring to an imaging surface using an infrared or fluorescence scanner (e.g., LI-COR Odyssey) [15] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of an EMSA requires careful selection and optimization of key reagents.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for EMSA Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled Nucleic Acid | IRDye 700-end-labeled dsDNA [15], Cy3-labeled probe [7], ³²P-labeled DNA [10] | Tracer for detection; fluorescent labels offer safety and convenience |

| Non-specific Competitor | poly(dI·dC), sonicated salmon sperm DNA [2] | Absorbs proteins that bind DNA non-specifically, reducing background |

| Specific Competitor | Unlabeled wild-type oligonucleotide [2] | Confirms binding specificity by competing for the target protein |

| Binding Buffer Components | Tris/KCl, DTT, MgCl₂, ZnCl₂, glycerol, Tween 20 [15] [2] | Creates optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for the specific protein-DNA interaction |

| Antibodies for Supershift | Antibody against the target protein or an epitope tag (e.g., FLAG) [7] | Confirms protein identity in the complex by causing a further mobility "supershift" |

| Gel Matrix | Native polyacrylamide (4-8%) [15] [16], agarose | Resolves complex from free probe; polyacrylamide offers higher resolution for small complexes |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantification of the shifted (bound) and free nucleic acid bands allows for the determination of binding parameters. The fraction of bound nucleic acid (θ) is calculated as θ = [Bound] / ([Bound] + [Free]). By varying the protein concentration and measuring θ, one can generate a binding isotherm and determine the equilibrium association constant (K~a~) and the binding stoichiometry [10].

Controls are vital for correct interpretation:

- Specific Competition: Inclusion of a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled specific competitor should abolish or drastically reduce the shifted band [2].

- Antibody Supershift: An antibody against the protein of interest can further retard the complex, confirming its presence [7].

- Mutant Competitor: An unlabeled oligonucleotide with a mutated binding site should not compete effectively for binding, demonstrating sequence specificity.

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay remains a powerful, versatile, and accessible technique for probing the equations that govern protein-nucleic acid binding equilibria. Through careful experimental design, optimization of binding conditions, and the use of robust controls and modern detection methods, researchers can extract quantitative thermodynamic data critical for understanding gene regulation, designing therapeutic interventions, and advancing molecular life sciences.

Advantages and Inherent Limitations of the EMSA Technique

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), also known as a gel shift or gel retardation assay, is a fundamental technique in molecular biology for studying interactions between nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) and proteins [17]. Since its development, EMSA has become a cornerstone method for detecting and analyzing these interactions, which are crucial for understanding fundamental biological processes such as gene regulation, transcription, DNA repair, and replication [18] [19]. The technique is prized for its simplicity, sensitivity, and versatility, allowing researchers to probe binding events under a wide range of conditions. However, despite its widespread use, EMSA possesses several inherent limitations that must be carefully considered during experimental design and data interpretation. This article provides a detailed examination of both the advantages and limitations of EMSA, supplemented with application notes and protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principle of EMSA

The fundamental principle of EMSA is based on the observation that the electrophoretic mobility of a nucleic acid molecule through a non-denaturing gel is retarded upon binding to a protein [17] [19]. When a mixture of free nucleic acids and nucleic acid-protein complexes is subjected to gel electrophoresis, the larger, often more charged, protein-nucleic acid complexes migrate more slowly through the gel matrix than the smaller, unbound nucleic acids. This results in a distinct "shift" in the band position when visualized, indicating a binding event has occurred [20].

EMSA Basic Workflow: This diagram illustrates the core steps of an EMSA experiment, from the binding reaction to the final detection of shifted complexes.

Advantages of the EMSA Technique

EMSA remains a popular technique due to a compelling set of advantages that make it suitable for many laboratory applications.

Table 1: Key Advantages of the EMSA Technique

| Advantage | Description | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Simplicity and Robustness [18] [17] [19] | The assay is straightforward to perform and can be successfully conducted under a wide spectrum of conditions. | Accessible to most laboratories without the need for highly specialized equipment. |

| High Sensitivity [17] [19] | Capable of detecting binding events at low nanomolar concentrations (even below 0.1 nM) with small sample volumes (less than 20 µl). | Conserves precious protein or nucleic acid samples. |

| Direct Measurement of Affinity [18] [19] | Can be used to determine apparent dissociation constants (Kd) by titrating protein into a fixed concentration of nucleic acid and quantifying the bound fraction. | Provides quantitative data on binding strength. |

| Flexibility in Sample Type [19] | Effective with both purified recombinant proteins and crude protein extracts (e.g., nuclear extracts). | Useful for identifying DNA-binding proteins present in complex mixtures. |

| Versatility in Conditions [17] | The assay buffer conditions (temperature: 0–60°C, pH: 4–9.5, salt concentration: 1–300 mM) can be modified over a wide range. | Allows for the study of diverse nucleic acid-protein complexes under near-physiological or specific conditions. |

| Analysis of Complex Size and Stoichiometry | The degree of mobility shift can provide information about the size and number of proteins bound to the nucleic acid. | Aids in characterizing the nature of the complex formed. |

Inherent Limitations of the EMSA Technique

Despite its utility, EMSA is not without its drawbacks, which can impact the interpretation of results and the applicability of the technique for certain scientific questions.

Table 2: Key Limitations of the EMSA Technique

| Limitation | Description | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Complex Dissociation [17] [19] | The protein-nucleic acid complex may dissociate during electrophoresis due to the non-equilibrium nature of the process. | Can lead to false negatives or underestimation of binding affinity. |

| No Sequence Specificity Information [18] [17] | EMSA confirms binding but does not identify the exact nucleotide sequence to which the protein is bound. | Requires complementary techniques (e.g., footprinting) to map binding sites. |

| Not Suitable for Kinetic Studies [19] | As an end-point assay, it does not provide real-time data on association or dissociation rates (kon, koff). | Limited utility for studying binding dynamics. |

| Influence of Non-Size Factors on Mobility [17] [19] | Electrophoretic mobility is influenced not only by molecular weight but also by the complex's charge, shape, and induced bends in the DNA. | Can complicate the interpretation of the complex's composition. |

| Potential for Non-Specific Binding [21] [18] | Highly charged molecules like oligonucleotides can bind non-specifically to filters or lab plastics. | May cause over- or underestimation of the free fraction and requires careful optimization with blockers. |

| Cumbersome Protocol [18] | The multi-step process, including gel preparation, electrophoresis, and detection, can be time-consuming. | Lower throughput compared to some modern, solution-based methods. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Fluorescence-Based EMSA

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for performing a non-radioactive EMSA using fluorescently labeled DNA, adapted from modern approaches [9] [22].

Materials and Reagent Preparation

- Binding Buffer: 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 2.5% Glycerol, and 0.1% NP-40. Store at 4°C.

- Non-denaturing Polyacrylamide Gel: A 6% gel (19:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) in 0.5X TBE buffer. Add 100 µL of 10% ammonium persulfate and 10 µL of TEMED per 10 mL of gel solution to polymerize.

- Fluorescently-Labeled DNA Probe: A 20-40 bp double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing the protein-binding site, end-labeled with an infrared fluorescent dye (e.g., IRDye) [22].

- Protein Sample: Purified recombinant protein or nuclear extract in a suitable storage buffer.

- Electrophoresis Equipment: Mini-gel apparatus and a compatible power supply.

- Imaging System: An infrared imaging system such as the Odyssey CLx Imager [22].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Detailed EMSA Protocol: This workflow outlines the key experimental steps, including the essential control reactions.

Gel Preparation and Pre-run: Pour a 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5X TBE. Allow it to polymerize completely. Assemble the gel apparatus with 0.5X TBE as the running buffer. Pre-run the gel for 30-60 minutes at 100 V to equilibrate the temperature and remove excess persulfate.

Binding Reaction:

- Prepare the following reactions in low-adhesion microcentrifuge tubes on ice (typical total volume: 20 µL):

- Reaction 1 (Control): 1 µL of labeled DNA probe (~10-20 fmol), 18 µL of binding buffer, 1 µL of nuclease-free water.

- Reaction 2 (Test): 1 µL of labeled DNA probe, 18 µL of binding buffer, 1 µL of protein sample.

- Reaction 3 (Specificity Control): 1 µL of labeled DNA probe, 18 µL of binding buffer, 1 µL of protein sample, and a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled identical competitor DNA.

- Mix the reactions gently by pipetting and centrifuge briefly.

- Incubate the reactions for 20-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Prepare the following reactions in low-adhesion microcentrifuge tubes on ice (typical total volume: 20 µL):

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Stop the pre-run and carefully clean the wells of the gel with a syringe.

- Add a minimal amount of non-denaturing loading dye to each reaction (or load the dye in a separate lane).

- Load the samples onto the gel.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 100 V (maintaining ~10 V/cm) for approximately 1-2 hours, or until the dye front has migrated an appropriate distance. It is critical to run the gel in a cold room or with a cooling apparatus to prevent complex dissociation due to heating.

Detection and Visualization:

- Carefully disassemble the gel plates. The gel can be imaged directly without transfer or drying.

- Place the wet gel (still on its glass plate) directly onto the scanner bed of an Odyssey CLx Imager or similar system.

- Acquire the image using the appropriate channel for the fluorescent dye (e.g., 700 nm or 800 nm channel).

- The result should show a fast-migrating band for the free probe (Reaction 1). A successful binding reaction (Reaction 2) will show a slower-migrating "shifted" band. The specificity of this shift is confirmed if it is abolished by the excess unlabeled competitor (Reaction 3).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for EMSA Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled Nucleic Acid Probe [17] [22] | The molecule whose binding is being studied; the label enables detection. | Can be radioisotope (³²P), fluorophore (IRDye, FAM), biotin, or digoxigenin-labeled. Choice depends on safety, sensitivity, and available detection equipment. |

| Non-denaturing Polyacrylamide Gel [17] | Matrix for separating bound from unbound nucleic acids based on size/charge. | Concentration (typically 4-10%) affects resolution. Must be non-denaturing to preserve protein-nucleic acid interactions. |

| Binding Buffer [17] | Provides the chemical environment (pH, ionic strength, cofactors) for the binding reaction. | Components (HEPES, KCl, glycerol, DTT, EDTA) can be optimized for specific protein-nucleic acid interactions. |

| Purified Protein or Nuclear Extract [19] | The binding partner of interest. | Purity and concentration are critical. Crude extracts can be used but may contain competing or non-specific factors. |

| Specific & Non-specific Competitor DNA [17] | Unlabeled nucleic acids used to confirm binding specificity (e.g., poly(dI:dC), salmon sperm DNA). | Specific competitor is identical to the probe; non-specific competitor has an unrelated sequence. |

| Electrophoresis System | Provides the electric field to drive separation. | Standard vertical mini-gel systems are commonly used. Temperature control is often necessary. |

Application Note: EMSA in Oligonucleotide Therapeutic Development

EMSA finds specialized applications in modern drug development, particularly for oligonucleotide therapeutics. Traditional plasma protein binding (PPB) studies for small molecules often use equilibrium dialysis, but this method is not viable for large, charged oligonucleotides due to poor diffusion through dialysis membranes [21]. Here, an optimized ultrafiltration method coupled with EMSA principles can be applied.

Challenge: Oligonucleotides exhibit strong non-specific binding to filter membranes, leading to underestimated free fraction (fu) values [21].

EMSA-Informed Solution: An EMSA can serve as an alternative or orthogonal method to estimate PPB for oligonucleotides [21]. The assay can resolve protein-bound oligonucleotides from free oligonucleotides based on mobility. Key considerations for this application include:

- Using an optimized ultrafiltration device with a large molecular weight cut-off (e.g., 50 kDa) to improve recovery.

- Pre-treating filter surfaces with detergents (e.g., Tween) to reduce non-specific binding, though this may impact protein binding itself.

- Recognizing that dilution steps required for EMSA may disrupt the binding equilibrium before measurement, which must be accounted for in data interpretation [21].

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay remains a powerful, accessible, and highly sensitive technique for the initial detection and quantitative analysis of nucleic acid-protein interactions. Its strengths of simplicity, flexibility, and the ability to provide direct visual evidence of binding make it an indispensable tool in the molecular biologist's arsenal. However, researchers must be acutely aware of its inherent limitations, including the potential for complex dissociation, the lack of information on binding site specificity, and the influence of factors beyond size on mobility. A thorough understanding of both the advantages and limitations of EMSA, combined with carefully designed controls and protocols as outlined in this article, is essential for generating robust and reliable data. As the field advances, adaptations of EMSA, such as those utilizing near-infrared fluorescence or applied to novel therapeutic oligonucleotides, continue to extend its utility in basic research and drug development.

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) stands as a fundamental pillar in molecular biology for detecting interactions between proteins and nucleic acids (DNA or RNA). This technique, also known as a gel shift or gel retardation assay, operates on a simple yet powerful principle: when a protein binds to a nucleic acid fragment, it forms a larger, bulkier complex that migrates more slowly through a non-denaturing gel matrix than the free nucleic acid does. This difference in migration speed results in a visible "shift" in the position of the band on the gel, providing direct evidence of an interaction [23]. For over three decades, EMSA has remained the "go-to assay" for investigating qualitative interactions, and with advances in imaging technologies, its role has expanded to include robust quantitative analyses [24].

The broad applicability of EMSA stems from its significant advantages. The technique is relatively simple to perform yet robust, accommodating a wide range of binding conditions, including variations in temperature, pH, and salt concentration [10]. It is highly sensitive, capable of detecting interactions with protein and nucleic acid concentrations as low as 0.1 nM when using radioisotope-labeled nucleic acids [10]. Furthermore, EMSA is versatile, working with nucleic acids of various sizes and structures—from short oligonucleotides to molecules several thousand nucleotides long, and including single-stranded, duplex, and quadruplex forms [10]. This combination of simplicity, sensitivity, and versatility accounts for the continuing popularity of EMSA in studying gene regulatory mechanisms.

Key Biological Processes Probed by EMSA

Transcription Factor Binding and Gene Regulation

One of the most classical applications of EMSA is in the study of transcription factors—proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences to activate or repress gene transcription. By using DNA probes containing a suspected transcription factor binding site, researchers can employ EMSA to confirm the interaction, determine its specificity through competition experiments, and identify the exact protein involved via supershift assays with specific antibodies [23]. This application is fundamental to understanding the transcriptional control of genes involved in development, cell cycle progression, and stress responses. The ability to resolve complexes of different stoichiometries or geometries further allows scientists to dissect the assembly of multi-protein complexes on DNA, a common theme in the formation of enhanceosomes and other regulatory complexes [25].

Hox Gene Function and DNA Binding

Hox genes, which encode a family of transcription factors critical for determining the anteroposterior axis during bilaterian animal development, represent a specific and biologically significant application of EMSA. These genes act as master regulators, controlling the expression of downstream target genes important for development. The EMSA protocol has been specifically adapted to measure Hox-DNA binding, allowing researchers to not only visualize protein-DNA complexes but also quantify protein affinity and cooperativity [25].

Research on the Hox gene Antennapedia (Antp) in the lepidopteran Bombyx mori provides a compelling example. While traditionally associated with embryonic patterning, Antp was found to regulate the expression of silk protein genes like sericin-1 in the terminally differentiated silk gland tissue [26]. EMSA was crucial in demonstrating that the putative activator complex could bind to the upstream regions of these genes, strongly suggesting that Antp directly activates their expression [26]. This finding expanded the understanding of Hox gene function beyond developmental patterning to include roles in regulating physiological processes in differentiated tissues.

RNA-Protein Interactions and Post-Transcriptional Control

EMSA is equally powerful for studying interactions between proteins and RNA, which are central to post-transcriptional gene regulation. This includes the binding of proteins to messenger RNA (mRNA) that influence its splicing, stability, localization, and translation. A specific example involves the PAZ domain of the Argonaute 2 (Ago2) protein, a key component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [27]. The PAZ domain binds the 3'-end of guide small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and EMSA has been successfully used to determine the equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) for complexes between the human Ago2 PAZ domain and various native and chemically modified RNA oligonucleotides [27]. Such studies are vital for understanding the RNA interference pathway and for developing chemically modified siRNAs for therapeutic purposes, such as the FDA-approved drug Patisiran [27].

DNA Repair and Viral Replication Mechanisms

Other essential biological processes characterized using EMSA include DNA repair mechanisms and viral replication. EMSA allows researchers to study how DNA repair proteins recognize and bind to damaged DNA sites, a critical first step in initiating repair [23]. Similarly, in virology, EMSA has been applied to investigate the binding of viral proteins to host DNA or RNA, which is often a key event in viral replication and pathogenesis [23]. The assay's flexibility with different nucleic acid structures also enables the study of recombinase and integrase enzymes, which bind to specific DNA sequences to catalyze DNA rearrangement and integration events [23].

Essential EMSA Protocols and Methodologies

Standard EMSA for Binding Confirmation

The foundational EMSA protocol confirms whether a protein binds to a specific nucleic acid sequence. The procedure begins with preparing a labeled nucleic acid probe, which can be DNA or RNA. While radioactive labeling with ³²P was traditional, modern approaches often use fluorescent dyes (e.g., Cy3, Cy5) or biotin for chemiluminescent detection, which are safer and generate less background noise [24] [23]. The binding reaction is assembled by incubating the purified protein (or a nuclear extract) with the labeled probe in an appropriate binding buffer, which typically contains salts, buffering agents, carrier proteins like BSA, and non-specific competitors like poly(dI-dC) to reduce non-specific binding [27] [10].

The mixture is then loaded onto a non-denaturing polyacrylamide or agarose gel and subjected to electrophoresis. During electrophoresis, the electric field drives the molecules through the gel matrix. Free nucleic acid migrates relatively quickly, while the protein-nucleic acid complex, being larger and more bulky, is retarded, resulting in a shifted band. After electrophoresis, the gel is imaged using an method appropriate for the label (e.g., autoradiography for radioactive probes, fluorescence scanning, or chemiluminescence detection) [27] [24]. The presence of a shifted band indicates a successful interaction.

Quantitative EMSA for Affinity Determination (Kd)

To move beyond mere detection and quantify the strength of a protein-nucleic acid interaction, a quantitative EMSA is performed. This protocol involves titrating the protein concentration while keeping the concentration of the labeled nucleic acid probe constant across a series of binding reactions [27] [23]. After electrophoresis and imaging, the fraction of bound nucleic acid is quantified by measuring the intensity of the shifted band relative to the total nucleic acid intensity (free plus bound) in each lane.

The data is then plotted as the fraction bound versus the total protein concentration. A non-linear regression analysis of this binding curve is performed to determine the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), which is the protein concentration at which half of the nucleic acid is bound [27]. The Kd is a critical measure of binding affinity; a lower Kd indicates a tighter, higher-affinity interaction. This quantitative approach is essential for comparing the affinities of different protein mutants for the same nucleic acid or the same protein for different nucleic acid sequences or modifications [27].

Table 1: Key Solutions and Reagents for Quantitative EMSA

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Example Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled Nucleic Acid Probe | Tracer molecule to visualize and quantify the interaction; typically used at low, constant concentration. | Fluorescently tagged (SYBR Gold, Cy dyes) or biotinylated DNA/RNA oligonucleotide [27] [23]. |

| Binding Buffer | Provides optimal ionic strength and pH environment to support specific protein-nucleic acid interactions. | Often contains Tris or HEPES buffer, NaCl or KCl, Mg²⁺, DTT, glycerol, non-ionic detergent, and non-specific DNA/RNA [27] [10]. |

| Non-Denaturing Gel | Matrix for separating protein-nucleic acid complexes from free nucleic acid based on size and charge. | Typically 4-10% polyacrylamide or low-percentage agarose gel, cast and run in low-ionic-strength buffer like 0.5x TBE [27] [24]. |

Competitive and Supershift EMSA for Specificity and Identification

Two powerful variants of the standard EMSA provide additional layers of information about the protein-nucleic acid complex.

Competitive EMSA: This assay proves the specificity of the observed interaction. It involves performing binding reactions in the presence of an excess of unlabeled competitor nucleic acids. If the unlabeled competitor is identical to the labeled probe (specific competitor), it will compete for binding with the protein, leading to a decrease in the intensity of the shifted band. In contrast, a non-specific competitor (e.g., a random DNA sequence) will not effectively compete for binding, and the shifted band will remain strong [23]. This confirms that the protein's binding is sequence-specific.

Supershift EMSA: This assay identifies a specific protein component within a shifted complex. An antibody specific to the protein of interest is added to the binding reaction. If that protein is present in the complex, the antibody will bind to it, forming an even larger antibody-protein-nucleic acid complex. This "supershifted" complex migrates even more slowly than the original shifted complex, appearing higher up in the gel [24] [23]. This is a definitive way to confirm the identity of a binding protein, especially when using crude nuclear extracts containing many different proteins.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of an EMSA requires careful preparation and optimization of key reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for EMSA

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Protein / Nuclear Extract | The nucleic-acid binding protein of interest. | Source of binding activity; purity and activity must be determined for quantitative studies [25] [23]. |

| Nucleic Acid Probe | The DNA or RNA sequence to which the protein binds. | Must be designed with the specific binding site; can be labeled with fluorophores, biotin, or radioisotopes [27] [23]. |

| Non-Specific Competitor DNA | To block non-specific binding of proteins to the probe. | Commonly poly(dI-dC), sheared salmon sperm DNA, or other non-specific polymers [10]. |

| Native Gel Matrix | To separate complexes based on size/shape. | Polyacrylamide (for high resolution) or agarose (for larger complexes); must be non-denaturing [27] [24]. |

| Electrophoresis Buffer | To provide conductivity during separation. | Low ionic strength buffers like TBE or TAE; often matches the buffer used in the gel [27]. |

| Detection System | To visualize the free probe and shifted complex. | Systems include fluorescence imaging, chemiluminescence, or autoradiography, chosen based on the probe label [27] [24] [23]. |

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay remains an indispensable tool in the molecular biologist's arsenal, bridging fundamental research and therapeutic development. Its application in studying transcription factor binding, Hox gene function, RNA-protein interactions in RISC, and DNA repair mechanisms underscores its versatility and enduring relevance. The evolution of the technique from a qualitative tool to a quantitative one, coupled with the development of safer and more sensitive detection methods, ensures that EMSA will continue to provide critical insights into the molecular dialogues that govern cellular life. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering both the fundamental and advanced protocols of EMSA is essential for probing the intricacies of gene regulation and for validating the mechanisms of novel therapeutic compounds.

EMSA in Action: Step-by-Step Protocols and Diverse Research Applications

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) is a fundamental technique in molecular biology used to detect interactions between proteins and nucleic acids (DNA or RNA). This protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step guide for performing EMSA, from probe labeling to gel autoradiography, enabling researchers to study transcription factors, DNA-binding proteins, and their regulatory elements. The core principle of EMSA relies on the observation that protein-nucleic acid complexes migrate more slowly than free nucleic acids during non-denaturing polyacrylamide or agarose gel electrophoresis, resulting in a characteristic "shift" or "retardation" in mobility [2] [10]. This protocol is essential for researchers and drug development professionals investigating gene regulation mechanisms.

Table 1: Key Applications of EMSA in Nucleic Acid-Protein Interaction Research

| Application Area | Specific Use | Relevance in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Analysis | Identify sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins (e.g., transcription factors) in crude lysates [2]. | Study gene regulatory mechanisms and promoter/enhancer elements. |

| Binding Affinity & Kinetics | Measure thermodynamic and kinetic parameters of protein-nucleic acid interactions [2] [10]. | Quantitative analysis of binding strength and dynamics. |

| Mutagenesis Studies | Identify critical binding sequences within gene regulatory regions [2]. | Functional characterization of DNA motifs and protein domains. |

| Complex Stoichiometry | Resolve complexes of different stoichiometry or conformation [2] [10]. | Determine the number of protein molecules bound to a nucleic acid fragment. |

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for EMSA

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Probe | The labeled DNA or RNA fragment containing the protein's binding site. | Can be a short synthesized oligonucleotide (20-50 bp) or a longer PCR product/restriction fragment (100-500 bp) [2]. |

| Labeling Molecule | Allows for sensitive detection of the probe after electrophoresis. | Radioactive (³²P), biotin, digoxigenin, or fluorescent dyes (Cy3, Cy5) [2] [16] [7]. |

| DNA-Binding Protein | The protein of interest that interacts with the probe. | Can be a purified preparation, in vitro transcription product, or crude nuclear/cell extract [2]. |

| Non-specific Competitor DNA | Blocks non-specific binding of proteins to the labeled probe. | Poly(dI•dC), sonicated salmon sperm DNA [2] [28]. |

| Specific Competitor DNA | Unlabeled version of the probe; verifies binding specificity by competition. | Used as a control; a 200-fold molar excess is typically sufficient [2]. |

| Binding Buffer | Provides optimal ionic strength, pH, and co-factors for the protein-nucleic acid interaction. | Often contains salts, glycerol, DTT, non-ionic detergents, and sometimes divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺) [2]. |

| Gel Matrix | Resolves protein-nucleic acid complexes from free nucleic acid via electrophoresis. | Non-denaturing polyacrylamide (common) or agarose gel [2] [16]. |

| Detection System | Visualizes the shifted bands. | X-ray film (for radioactivity), phosphorimager, CCD camera for chemiluminescence (biotin/DIG) or fluorescent scanner [2] [16] [7]. |

Methodology

A. Probe Design and Labeling

The DNA probe is a critical component, and its design depends on the experimental goal. For well-defined binding sites, complementary oligonucleotides (20-50 bp) can be synthesized and annealed [2]. For studying multi-protein complexes, longer DNA fragments (100-500 bp) generated by PCR or restriction digestion are more appropriate [2].

Step-by-Step Protocol for Infrared Fluorescent Dye Labeling [16]:

Oligonucleotide Design:

- Design one long oligonucleotide (~51-mer) containing the target binding sequence.

- Design a complementary short oligonucleotide (~14-mer) with a melting temperature above 37°C. This short oligo is synthesized with an infrared fluorescent dye (e.g., IRDye) modification at its 5' terminus.

Annealing:

- In a 1.5 mL tube, mix 0.6 µL of the 5'-dye-labeled short oligo (100 µM), 1.2 µL of the long oligo (100 µM), and 28.2 µL of STE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA).

- Place the tube in boiling water for 5 minutes, then turn off the heat and allow the water to cool to room temperature overnight, protected from light.

Fill-in Reaction:

- Prepare a reaction mix with the 30 µL of annealed oligos, 8.5 µL of 10x Klenow buffer, 1.7 µL of 10 mM dNTPs, and 1.7 µL of Klenow fragment (3'→5' exo-).

- Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes.

- Stop the reaction by adding 3.4 µL of 0.5 M EDTA and heat-inactivating at 75°C for 20 minutes.

- Dilute the final double-stranded probe to a working concentration of 0.1 µM and store at -20°C in the dark.

Alternative Radioisotope Labeling (5' End-Labeling with ³²P): While not detailed in the searched protocols, a common method involves using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (T4 PNK) and [γ-³²P]ATP to transfer a radioactive phosphate group to the 5' end of a DNA oligonucleotide [2].

B. Binding Reaction

The binding reaction is where the protein and labeled probe interact. The order of addition of components is often critical for minimizing nonspecific binding [2].

Prepare the Reaction Mix: For a standard 20 µL reaction, combine the following components in order:

- Nuclease-free water (to 20 µL total volume)

- Binding Buffer (typically 10-20 mM Tris-HCl, 50-100 mM NaCl/KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 5% Glycerol [28])

- Non-specific Competitor DNA (e.g., 1 µg of poly(dI•dC))

- Protein Extract or Purified Protein

- Optional for competition controls: Unlabeled Specific Competitor DNA (add before the labeled probe)

- Labeled Probe (add last)

Incubate: Mix the components gently and incubate the reaction at room temperature (25°C) or 30°C for 20-30 minutes to allow complex formation [28].

Diagram 1: Binding Reaction Workflow

C. Non-Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis

A non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel is used to resolve the complexes from the free probe.

Gel Preparation: Prepare a 4-6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5x TBE buffer. For a 5%, 30 mL gel mixture [16]:

- 5 mL of 30% Acrylamide/Bis (37.5:1)

- 3 mL of 5x TBE

- 1.5 mL of 50% Glycerol (helps stabilize complexes and aids loading)

- 20.2 mL of ddH₂O

- 300 µL of 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS)

- 15 µL of TEMED

- Pour the gel immediately after adding APS and TEMED and allow it to polymerize.

Pre-electrophoresis and Sample Loading:

- Assemble the gel apparatus and fill the tanks with 0.5x TBE running buffer.

- Pre-run the gel for 30-60 minutes at a constant voltage (e.g., 100 V) to establish a stable current and temperature.

- After the binding reaction incubation, add a small volume of non-denaturing loading dye (without SDS or bromophenol blue, which can disrupt complexes) to each sample.

- Load the samples onto the gel and run it at a constant voltage (e.g., 100 V) for 60-90 minutes or until the dye front has migrated sufficiently. Running the gel in a cold room (4°C) can help stabilize labile complexes.

D. Detection and Autoradiography

The detection method depends on the probe label used. This section details autoradiography for radiolabeled probes.

Gel Transfer (Optional but Recommended): For better handling and to prevent the gel from breaking during the drying process, the separated complexes can be transferred from the gel onto a positively charged nylon membrane using a wet or semi-dry transfer system [28].

Cross-linking: If a membrane transfer was performed, the nucleic acids are cross-linked to the membrane using a UV cross-linker. This step is not needed if detecting directly in the gel.

Autoradiography:

- For Gels: Dry the gel under vacuum on a gel dryer. In a darkroom, place the dried gel (or the membrane) in an autoradiography cassette.

- Exposure: Place a sheet of X-ray film directly against the gel/membrane in the cassette. Close the cassette and expose it at -80°C for several hours to days, depending on the signal intensity [29].

- Development: Develop the film using an automated film processor or manually in a darkroom using developer and fixer solutions.

Diagram 2: Autoradiography Detection Pathway

Anticipated Results and Interpretation

A successful EMSA will show one or more bands corresponding to the free probe at the bottom of the gel/autoradiograph. A specific protein-DNA interaction is confirmed by the appearance of a higher molecular weight "shifted" band. The specificity of this band is validated by its disappearance or significant reduction when a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled specific competitor (cold probe) is included in the reaction. The inclusion of a non-specific competitor DNA (e.g., poly(dI•dC)) should not affect the intensity of the specific shifted band [2].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common EMSA Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No shifted band | Protein not active or present in sufficient concentration. | Use fresh protein extract, check protein activity, increase protein amount. |

| Complex dissociates during electrophoresis. | Optimize binding buffer (e.g., add Mg²⁺), run gel at 4°C, shorten run time [10]. | |

| High background or smearing | Non-specific binding. | Increase concentration of non-specific competitor DNA, optimize salt concentration in binding buffer [2]. |

| Multiple shifted bands | Multiple proteins binding to the probe. | Use purified protein instead of crude extract. Perform a "supershift" assay with a specific antibody to identify proteins in the complex [10]. |

| Faint or no signal | Inefficient probe labeling. | Check labeling efficiency, increase exposure time for autoradiography [29]. |

Discussion

EMSA remains a cornerstone technique for studying protein-nucleic acid interactions due to its simplicity, sensitivity, and ability to provide qualitative and semi-quantitative data [10]. The protocol outlined above allows for the detection of specific binding events using either radioactive or non-radioactive detection methods.

Recent advancements have expanded the utility of EMSA. The development of fluorescent EMSA (fEMSA) using infrared or Cy3-labeled probes offers a safer and faster alternative to radioactivity, allowing direct in-gel detection without post-electrophoresis processing like transfer or film exposure [16] [7]. Furthermore, innovative approaches such as isolating proteins directly from host plants (PPF-EMSA) ensure that the proteins are in their natural state with correct folding and post-translational modifications, which can be critical for authentic binding activity [7].

A key limitation of EMSA is that the assay is not at equilibrium during electrophoresis, which can lead to dissociation of labile complexes and underestimation of binding affinity [10]. Additionally, EMSA does not directly identify the protein(s) in the complex or the precise binding site location, though these can be addressed with supershift assays or combined with footprinting techniques, respectively [10]. Despite these limitations, when performed with appropriate controls, EMSA is an powerful and indispensable tool for confirming direct nucleic acid-protein interactions in vitro.

The Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) is a fundamental technique for studying nucleic acid-protein interactions, central to processes like transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, and viral assembly [2] [10]. This assay operates on the principle that protein-nucleic acid complexes migrate more slowly than free nucleic acids during non-denaturing gel electrophoresis, resulting in a detectable "shift" or "retardation" [2] [10]. The core of a successful EMSA experiment lies in the effective design and labeling of the nucleic acid probe, which serves as the binding target for the protein of interest.

Effective probe design requires careful consideration of the binding sequence and structural context. For studying specific transcription factors or DNA-binding proteins, short double-stranded oligonucleotides (typically 20-50 base pairs) containing the precise binding sequence are often sufficient [2]. These can be economically synthesized as complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides and annealed to form duplexes. For more complex studies involving multi-protein complexes or multiple binding sites, longer DNA fragments (100-500 base pairs) generated via PCR or restriction digestion may be necessary [2]. These longer fragments typically require gel purification to remove enzymes and template DNA that could cause nonspecific competition [2].

Critical to probe design is the incorporation of appropriate labeling strategies that enable sensitive detection without interfering with protein-binding activity. The choice of labeling method—radioactive, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent—impacts the sensitivity, safety, cost, and experimental workflow of the EMSA procedure. Each method employs distinct chemistries and detection systems, requiring researchers to match the approach to their specific experimental needs and available resources.

Probe Labeling Methodologies: Principles and Protocols

Radioactive Labeling with ³²P

Traditional radioactive labeling using ³²P has been the gold standard for EMSA detection due to its exceptional sensitivity [10]. This method typically employs the [γ-³²P]ATP with T4 polynucleotide kinase for 5' end-labeling or [α-³²P]dNTP with Klenow fragment for 3' end-labeling during fill-in reactions [2]. The fundamental advantage of radioactive detection lies in its ability to detect very low concentrations of protein-DNA complexes (as low as 0.1 nM) with minimal interference to the binding interaction [10]. However, growing concerns about safety regulations, disposal costs, and isotope half-life have prompted many laboratories to transition to non-radioactive alternatives [2] [16].

Table 1: Radioactive Labeling Protocol Overview