Gene Expression and Regulation: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Clinical Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of gene expression and regulation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Gene Expression and Regulation: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Clinical Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of gene expression and regulation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the fundamental principles of transcriptional and post-transcriptional control, including the roles of transcription factors, enhancers, and chromatin structure. The scope then progresses to cover state-of-the-art methodological approaches for profiling gene expression, such as RNA-Seq and single-cell analysis, and their application in identifying disease biomarkers and therapeutic targets. The content further addresses common challenges in data interpretation and analysis optimization, including the integration of multi-omics data. Finally, it offers a comparative evaluation of computational tools for pathway enrichment and network analysis, validating findings through case studies in cancer and infectious disease. This resource synthesizes foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications to bridge the gap between basic research and clinical translation.

The Core Machinery: Unraveling Fundamental Mechanisms of Gene Control

The Central Dogma and Fundamental Principles

Gene expression represents the fundamental process by which the genetic code stored in DNA is decoded to direct the synthesis of functional proteins that execute cellular functions. This process involves two principal stages: transcription, where a DNA sequence is copied into messenger RNA (mRNA), and translation, where the mRNA template is read by ribosomes to assemble a specific polypeptide chain. The regulation of these processes determines cellular identity, function, and response to environmental cues, with disruptions frequently leading to disease states [1].

The orchestration of gene expression extends beyond the simple protein-coding sequence to include complex regulatory elements that control the timing, location, and rate of expression. Whereas the amino acid code of proteins has been understood for decades, the principles governing the expression of genes—the cis-regulatory code of the genome—have proven more complex to decipher [1]. Recent technological advances have transformed our understanding from a "murky appreciation to a much more sophisticated grasp of the regulatory mechanisms that orchestrate cellular identity, development, and disease" [1].

Molecular Mechanisms of Transcription and Translation

Transcription: DNA to RNA

Transcription initiates when RNA polymerase binds to a specific promoter region upstream of a gene, unwinding the DNA double helix and synthesizing a complementary RNA strand using one DNA strand as a template. In eukaryotic cells, this primary transcript (pre-mRNA) undergoes extensive processing including 5' capping, 3' polyadenylation, and RNA splicing to remove introns and join exons, resulting in mature mRNA that is exported to the cytoplasm [2].

The splicing process represents a critical layer of regulation, where alternative splicing of the same pre-mRNA can generate multiple protein isoforms with distinct functions from a single gene. Post-transcriptional regulation has emerged as a key layer of gene expression control, with methodological advances now enabling researchers to differentiate co-transcriptional from post-transcriptional splicing events [3].

Translation: RNA to Protein

Translation occurs on ribosomes where transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules deliver specific amino acids corresponding to three-nucleotide codons on the mRNA template. The ribosome catalyzes the formation of peptide bonds between adjacent amino acids, generating a polypeptide chain that folds into a functional three-dimensional protein structure. Translation efficiency is influenced by multiple factors including mRNA stability, codon usage bias, and regulatory RNA molecules.

Regulatory Mechanisms Governing Gene Expression

Gene expression is regulated at multiple levels through sophisticated mechanisms that ensure precise spatiotemporal control:

Transcriptional Regulation

Cis-regulatory elements, including promoters, enhancers, silencers, and insulators, control transcription initiation by serving as binding platforms for transcription factors. Enhancer elements can be located great distances from their target genes, with communication facilitated through three-dimensional genome organization that brings distant regulatory elements into proximity with promoters [3]. The development of technologies such as ChIP-seq (chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing) has enabled genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding sites, revealing the complexity of transcriptional networks [2].

Post-Transcriptional Regulation

After transcription, gene expression can be modulated through RNA editing, transport from nucleus to cytoplasm, subcellular localization, stability, and translation efficiency. MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs can bind to complementary sequences on target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation. Recent attention has focused on the potential of circular RNAs as stable regulatory molecules with therapeutic potential [3].

Epigenetic Mechanisms

DNA methylation and histone modifications create an epigenetic layer that regulates chromatin accessibility and gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These heritable modifications can be influenced by environmental factors and play crucial roles in development, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis [3].

Table 1: Key Levels of Gene Expression Regulation

| Regulatory Level | Key Mechanisms | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional | Transcription factor binding, chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation, 3D genome organization | Determines which genes are accessible for transcription and initial transcription rates |

| Post-transcriptional | RNA splicing, editing, export, localization, and stability | Generates diversity from limited genes and fine-tunes expression timing and location |

| Translational | Initiation factor regulation, miRNA targeting, codon optimization | Controls protein synthesis rate and efficiency in response to cellular needs |

| Post-translational | Protein folding, modification, trafficking, and degradation | Determines final protein activity, localization, and half-life |

Advanced Research Methodologies and Technologies

Sequencing-Based Approaches

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomic analysis by enabling researchers to examine individual cells with unprecedented resolution, revealing previously uncharacterized cell types, transient regulatory states, and lineage-specific transcriptional programs [1] [4]. Different scRNA-seq protocols offer distinct advantages: full-length transcript methods (Smart-Seq2, MATQ-Seq) excel in isoform usage analysis and detection of low-abundance genes, while 3' end counting methods (Drop-Seq, inDrop) enable higher throughput at lower cost per cell [4].

Long-read sequencing technologies have transformed genomics by illuminating previously inaccessible repetitive genomic regions and enabling comprehensive characterization of full-length RNA isoforms, revealing the complexity of alternative splicing and transcript diversity [1]. The development of nascent transcription quantification methods like scFLUENT-seq provides quantitative, genome-wide analysis of transcription initiation in single cells [3].

Computational and Machine Learning Approaches

Deep learning and artificial intelligence are playing a pivotal role in decoding the regulatory genome, with models trained on large-scale datasets to identify complex DNA sequence patterns and dependencies that govern gene regulation [1]. Sequence-to-expression models can predict gene expression levels directly from DNA sequence, providing new insights into the combinatorial logic underlying cis-regulatory control [3]. Benchmarking platforms like PEREGGRN enable systematic evaluation of expression forecasting methods across diverse cellular contexts and perturbation conditions [5].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of scRNA-seq Technologies

| Protocol | Isolation Strategy | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Amplification Method | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 | FACS | Full-length | No | PCR | Enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts |

| Drop-Seq | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | High-throughput, low cost per cell, scalable to thousands of cells |

| inDrop | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | IVT | Uses hydrogel beads, low cost per cell |

| MATQ-Seq | Droplet-based | Full-length | Yes | PCR | Increased accuracy in quantifying transcripts |

| SPLiT-Seq | Not required | 3'-only | Yes | PCR | Combinatorial indexing without physical separation, highly scalable |

Experimental Workflows and Technical Protocols

RNA Sequencing Analysis Pipeline

Comprehensive gene expression analysis requires integrated bioinformatics workflows. The exvar R package exemplifies such an integrated approach, providing functions for Fastq file preprocessing, gene expression analysis, and genetic variant calling from RNA sequencing data [6]. The standard workflow begins with quality control using tools like rfastp, followed by alignment to a reference genome, gene counting using packages like GenomicAlignments, and differential expression analysis with DESeq2 [6].

For functional interpretation, gene ontology enrichment analysis can be performed using AnnotationDbi and ClusterProfiler packages, with results visualized in barplots, dotplots, and concept network plots [6]. Integrated analysis platforms increasingly support multiple species including Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Arabidopsis thaliana, and other model organisms, though limitations exist due to the availability of species-specific annotation packages [6].

Perturbation Studies and Functional Validation

CRISPR-based screening approaches enable systematic functional characterization of regulatory elements. Tools like Variant-EFFECTS combine prime editing, flow cytometry, sequencing, and computational analysis to quantify the effects of regulatory variants at scale [1] [3]. In vivo CRISPR screening methods have advanced to allow functional validation of regulatory elements in their native contexts [1].

Perturbation-seq technologies (e.g., Perturb-seq) enable coupled genetic perturbation and transcriptomic readout, generating training data for models that forecast expression changes in response to novel genetic perturbations [5]. Benchmarking studies indicate that performance varies significantly across cellular contexts, with integration of prior knowledge (e.g., TF binding from ChIP-seq) often improving prediction accuracy [5].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Expression Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Poly[T] primers | Selective capture of polyadenylated mRNA | scRNA-seq protocols to minimize ribosomal RNA contamination |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Barcoding individual mRNA molecules | Accurate quantification of transcript abundance in high-throughput scRNA-seq |

| Reverse transcriptase | Synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates | First step in most RNA-seq protocols |

| Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) | Precise genome editing | CRISPR-based perturbation studies in primary cells |

| Prime editing systems | Precise genome editing without double-strand breaks | Functional characterization of regulatory variants |

| dCas9-effector fusions | Targeted transcriptional activation/repression | CRISPRa/CRISPRi perturbation studies without altering DNA sequence |

| Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) grade antibodies | Enrichment of DNA bound by specific proteins | Mapping transcription factor binding sites and histone modifications |

| Transposase (Tn5) | Tagmentation of chromatin | ATAC-seq for mapping accessible chromatin regions |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

Gene expression programs are embedded within complex regulatory networks that respond to extracellular signals, intracellular cues, and environmental challenges. Signaling pathways such as Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog, and receptor tyrosine kinase pathways ultimately converge on transcription factors that modulate gene expression patterns. These networks exhibit properties of robustness, feedback control, and context-specificity, enabling appropriate cellular responses to diverse stimuli.

Transcriptional condensates have emerged as potential temporal signal integrators—membleneless organelles that concentrate molecules involved in gene regulation and may serve as decoding mechanisms that transmit information through gene regulatory networks governing cellular responses [3]. The interplay between signaling pathways, transcriptional regulation, and post-transcriptional processing creates multi-layered control systems that enable complex cellular behaviors.

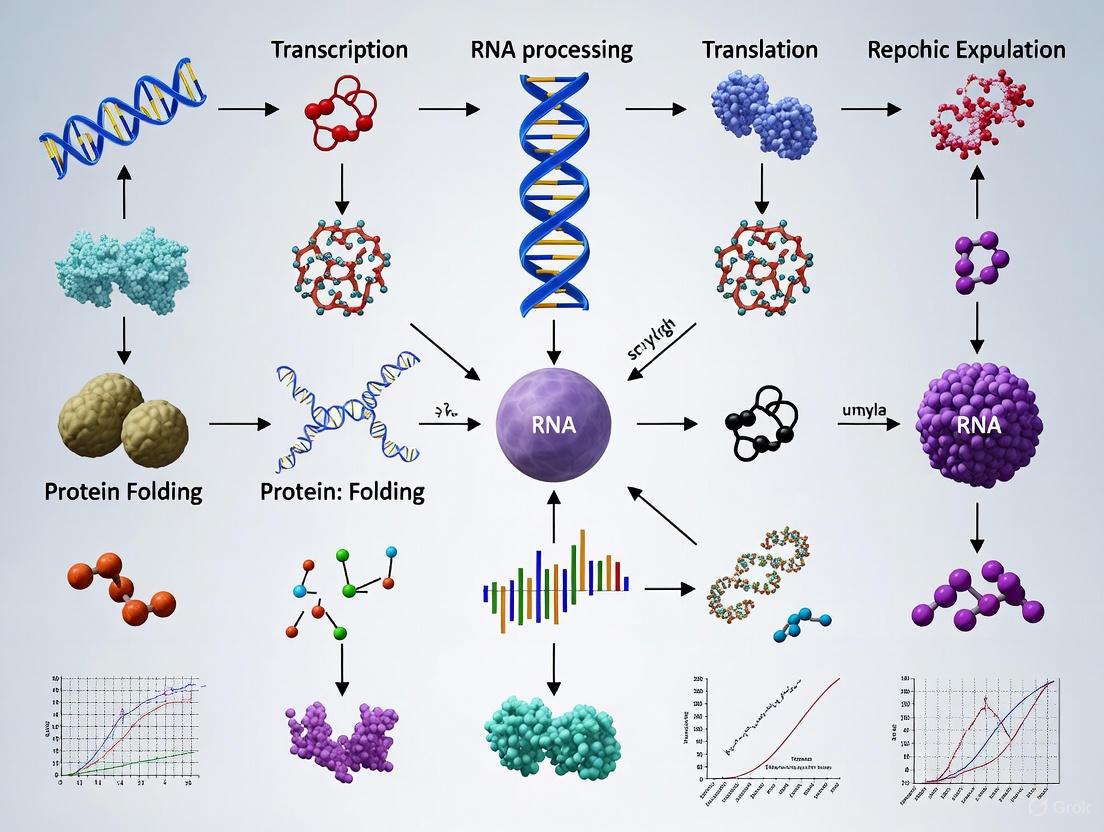

Visualizing Gene Expression Workflows

Central Pathway of Gene Expression

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow

Future Directions and Clinical Applications

The field of gene expression research is rapidly evolving toward more predictive, quantitative models. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) approaches are being integrated with mutational and clinical features to identify genomic signatures for disease prognosis and treatment response [2]. Large-scale biobank resources are enabling regulatory genomics at unprecedented scales, revealing how variation in gene regulation shapes human traits and disease susceptibility [3].

In personalized medicine, gene expression profiling identifies potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets, as exemplified by studies on the ACE2 receptor and prostate cancer [6]. Spatial transcriptomics technologies are advancing to localize gene expression patterns within tissue architecture, with ongoing developments aiming to integrate microRNA detection into spatial biology [3].

The integration of multi-omics datasets—including genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—promises more comprehensive models of gene regulatory networks. As these technologies mature, they will continue to transform our understanding of basic biology and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies for human disease.

Gene expression is the fundamental process by which functional gene products are synthesized from the information stored in DNA, with transcription serving as the first and most heavily regulated step [7]. The precise control of when, where, and to what extent genes are transcribed is governed by the intricate interplay between cis-regulatory elements (such as promoters and enhancers) and trans-regulatory factors (including transcription factors and RNA polymerase) [7] [8]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms is not merely an academic exercise; it provides a foundation for identifying novel therapeutic targets, understanding disease pathogenesis, and developing drugs that can modulate gene expression patterns with high specificity [9] [10]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of the core components of the transcriptional machinery, recent advances in our understanding of regulatory mechanisms such as RNA polymerase pausing and transcriptional bursting, and the experimental approaches driving discovery in this field.

Core Components of the Transcriptional Machinery

Promoters and Enhancers: The Genomic Control Elements

Promoters are DNA sequences typically located proximal to the transcription start site (TSS) of a gene. They serve as the primary platform for assembling the transcription pre-initiation complex (PIC). While core promoter elements are conserved, their specific sequence and architecture contribute significantly to the variable transcriptional output of different genes [11].

Enhancers are distal regulatory elements that can be located thousands of base pairs away from the genes they control. They function to amplify transcriptional signals through looping interactions that bring them into physical proximity with their target promoters. This enhancer-promoter communication is a critical, often rate-limiting step in gene activation and is facilitated by transcription factors, coactivators, and architectural proteins that mediate chromatin looping [11] [8].

RNA Polymerase II: The Enzymatic Core

RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII) is the multi-subunit enzyme responsible for synthesizing messenger RNA (mRNA) and most non-coding RNAs in eukaryotes. The journey of RNAPII through a gene is a multi-stage process:

- Recruitment and Initiation: RNAPII is recruited to the promoter region, where it assembles into the PIC.

- Promoter-Proximal Pausing: After initiating transcription and synthesizing a short RNA transcript (20–60 nucleotides), RNAPII frequently pauses. This pausing is a major regulatory checkpoint for ~30–50% of genes [12].

- Elongation and Termination: Upon receiving the appropriate signals, RNAPII is released into productive elongation, transcribing the full length of the gene before terminating [11] [12].

Transcription Factors and Coactivators: The Regulators

Transcription Factors (TFs) are sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins that recognize and bind to enhancer and promoter elements. They function as activators or repressors and can be classified by their DNA-binding domains (e.g., zinc fingers, helix-turn-helix). The binding of TFs to their cognate motifs is influenced by motif strength, chromatin accessibility, and the cellular concentration of the TFs themselves [12] [13].

Coactivators are multi-protein complexes that do not bind DNA directly but are recruited by TFs to execute regulatory functions. Key coactivators include the Mediator complex, which facilitates interactions between TFs and RNAPII, and chromatin-modifying enzymes like the BAF complex, which remodels nucleosomes to create accessible chromatin [11] [12].

Table 1: Core Components of the Eukaryotic Transcriptional Machinery

| Component | Molecular Function | Key Features | Regulatory Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter | DNA sequence for PIC assembly | Located near TSS; contains core elements (e.g., TATA box) | Determines transcription start site and basal transcription level |

| Enhancer | Distal transcriptional regulator | Binds TFs; can be located >1Mb from target gene; loops to promoter | Amplifies transcriptional signal; confers cell-type specificity |

| RNA Polymerase II | mRNA synthesis enzyme | Multi-subunit complex; undergoes phosphorylation during cycle | Catalytic core; its pausing and release are major regulatory steps |

| Transcription Factors | Sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins | Recognize 6-12 bp motifs; can be activators or repressors | Interpret regulatory signals and recruit co-regulators |

| Mediator Complex | Coactivator; molecular bridge | Large multi-subunit complex; interacts with TFs and RNAPII | Integrates signals from multiple TFs to facilitate PIC assembly |

Quantitative Models of Transcriptional Regulation

The regulation of gene expression is increasingly understood in quantitative terms. Thermodynamic models provide a framework for predicting transcription levels based on the equilibrium binding of proteins to DNA. The central tenet is that the level of gene expression is proportional to the probability that RNAP is bound to its promoter ((p_{bound})) [13].

This probability is calculated using statistical mechanics, considering all possible microstates of the system—specifically, the distribution of RNAP molecules between a specific promoter and a large number of non-specific genomic sites. The fold-change in expression due to a regulator is derived from the ratio of (p_{bound}) in the presence and absence of that regulator. This modeling reveals that the regulatory outcome depends not only on the binding affinities of TFs and RNAP for their specific sites but also on their concentrations and their affinity for the non-specific genomic background [13].

Advanced Regulatory Concepts

RNA Polymerase II Pausing and Release

A critical discovery in the past decade is that RNAPII frequently enters a promoter-proximal paused state after transcribing only 20–60 nucleotides. This pausing, stabilized by complexes like NELF and DSIF, creates a checkpoint that allows for the integration of multiple signals before a gene commits to full activation [11] [12].

Recent research illustrates the functional significance of pausing. A 2025 study on the estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) demonstrated that paused RNAPII can prime promoters for stronger activation. The paused polymerase recruits chromatin remodelers that create nucleosome-free regions (NFRs), exposing additional TF binding sites. Furthermore, the short, nascent RNAs transcribed by the paused polymerase can physically interact with and stabilize TFs like ERα on chromatin, leading to the formation of larger transcriptional condensates and a more robust transcriptional response upon release [12].

Transcriptional Bursting and Re-initiation

Live-cell imaging and single-cell transcriptomics have revealed that transcription is not a continuous process but occurs in stochastic bursts—short periods of high activity interspersed with longer periods of quiescence. Two key parameters define this phenomenon:

- Burst Frequency: How often a gene transitions from an inactive to an active state; often linked to enhancer-promoter communication and TF binding dynamics.

- Burst Size: The number of mRNA molecules produced per burst; largely determined by the number of RNAPII molecules that successfully re-initiate transcription from a promoter that is already in an active, "open" configuration [11].

RNAPII re-initiation is a process where multiple polymerases initiate from the same promoter in rapid succession during a single burst, significantly amplifying transcriptional output without the need to reassemble the entire pre-initiation complex for each round [11].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters in Transcriptional Regulation

| Parameter | Definition | Biological Influence | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burst Frequency | Rate of gene activation events | Controlled by enhancer strength, TF activation, chromatin accessibility | Live-cell imaging, single-cell RNA-seq |

| Burst Size | Number of transcription events per burst | Governed by re-initiation efficiency and pause-release dynamics | Live-cell imaging, single-cell RNA-seq |

| Polymerase Dwell Time | Duration TF remains bound to DNA | Impacts stability of transcriptional condensates and duration of bursts | Single Molecule Tracking (SPT/SPT) |

| Fold-Change | Ratio of expression with/without a regulator | Measures the regulatory effect of a TF (activation or repression) | RNA-seq, qPCR, thermodynamic modeling |

| Paused Index | Ratio of Pol II at promoter vs. gene body | Indicator of the prevalence of polymerase pausing for a given gene | ChIP-seq against Pol II (e.g., Pol IIS5P) |

Experimental Methods for Studying Transcription

Core Methodologies

A suite of powerful technologies enables researchers to dissect transcriptional mechanisms.

- RNA-seq (RNA Sequencing): A cornerstone method for transcriptome analysis. It involves converting a population of RNA (e.g., total, poly-A+) into a library of cDNA fragments, which are then sequenced en masse using high-throughput platforms. This allows for the genome-wide quantification of transcript levels, discovery of novel splice variants, and identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [7] [8].

- ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing): This technique identifies the genomic binding sites for TFs, histone modifications, or RNAPII itself. It involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, shearing the chromatin, immunoprecipitating the protein-DNA complexes with a specific antibody, and then sequencing the bound DNA fragments [8] [12].

- Single Molecule Tracking (SMT): SMT, a form of live-cell imaging, allows researchers to track the movement and binding dynamics of individual TFs in real time within the nucleus. It provides quantitative data on the bound fraction and residence time (dwell time) of TFs, parameters that are altered in different transcriptional states [12].

Integrated Experimental Workflows

The most powerful insights often come from integrating complementary methods. For instance, RNA-seq can first be used to identify a set of transcription factors and target genes that are differentially expressed in response to a stimulus (e.g., a drug or hormone). Subsequently, ChIP-seq for a specific TF from that list can directly map its binding sites to the promoters or enhancers of the responsive genes, thereby validating a putative regulatory network [8]. This integrated approach is crucial for distinguishing direct targets from indirect consequences in a gene regulatory cascade.

Diagram 1: Integrated RNA-seq and ChIP-seq Workflow. This pipeline shows how RNA-seq is used for gene discovery, followed by ChIP-seq for direct target validation, culminating in an integrated regulatory model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Transcriptional Regulation Research

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| TF-specific Antibodies | High-specificity immunoprecipitation of target transcription factors or chromatin marks. | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq, ChIP-qPCR) [8] [12] |

| Crosslinking Agents (e.g., Formaldehyde) | Covalently stabilizes protein-DNA interactions in living cells. | Preservation of in vivo binding events for ChIP-seq [8] |

| Polymerase Inhibitors (e.g., DRB, Triptolide) | DRB inhibits CDK9/pTEFb to block pause-release; Triptolide causes Pol II degradation. | Probing the functional role of Pol II pausing and elongation [12] |

| HaloTag / GFP Tagging Systems | Enables fluorescent labeling of proteins for live-cell imaging. | Single Molecule Tracking (SPT) and visualization of transcriptional condensates [12] |

| Stable Cell Lines | Genetically engineered lines with tagged proteins (e.g., ERα-GFP) or reporter constructs. | Consistent, reproducible models for imaging and functional studies [12] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Accurate amplification of cDNA and immunoprecipitated DNA fragments. | cDNA library construction for RNA-seq; amplification of ChIP-seq libraries [8] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The ability to modulate gene expression with small molecules represents a paradigm shift in pharmacology. Transcription-based pharmaceuticals offer several advantages over traditional drugs and recombinant proteins: they can be administered orally, are less expensive to produce, can target intracellular proteins, and have the potential for tissue-specific effects due to the unique regulatory landscape of different cell types [10].

Several approved drugs already work through transcriptional mechanisms. Tamoxifen acts as an antagonist of the estrogen receptor (a ligand-dependent TF) in breast tissue. The immunosuppressants Cyclosporine A and FK506 inhibit the TF NF-AT, preventing the expression of interleukin-2 and other genes required for T-cell activation. Even aspirin has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting NF-κB-mediated transcription [10].

Gene expression signatures are also used to guide drug development. The Connectivity Map database contains gene expression profiles from human cells treated with various drugs, allowing researchers to discover novel therapeutic applications for existing drugs or to predict mechanisms of action for new compounds based on signature matching [9].

The field of transcriptional regulation continues to evolve rapidly. Emerging areas of focus include understanding the role of biomolecular condensates—phase-separated, membraneless organelles that concentrate transcription machinery—in enhancing gene activation [12] [14]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence with functional genomics is poised to revolutionize our ability to predict regulatory outcomes from DNA sequence and to design synthetic regulatory elements for therapeutic purposes [15].

In conclusion, the core machinery of transcription—promoters, RNA polymerase, and transcription factors—operates not as a simple on-off switch, but as a sophisticated, quantitative control system. The discovery of regulated pausing, bursting, and re-initiation has added layers of complexity to our understanding of how genes are controlled. For researchers and drug developers, mastering these mechanisms provides a powerful toolkit for interrogating biology and designing the next generation of therapeutics that act at the most fundamental level of cellular control.

The central dogma of molecular biology has long recognized transcription as the first step in gene expression. However, the journey from DNA to functional protein involves sophisticated layers of regulation that occur after an RNA molecule is synthesized. RNA splicing, editing, and maturation represent critical post-transcriptional processes that dramatically expand the coding potential of genomes and enable precise control over gene expression outputs. These mechanisms allow single genes to produce multiple functionally distinct proteins and provide cells with rapid response capabilities without requiring new transcription events. Recent technological advances have revealed that these processes are not merely constitutive steps in RNA processing but are dynamically regulated across tissues, during development, and in response to cellular signals [16]. Furthermore, growing evidence establishes that dysregulation of these post-transcriptional mechanisms contributes significantly to human diseases, making them promising targets for therapeutic intervention [17] [18]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of the mechanisms, regulation, and experimental approaches for studying RNA splicing, editing, and maturation, framing these processes within the broader context of gene expression regulation research.

RNA Splicing: Mechanisms and Regulation

Core Splicing Machinery

RNA splicing is the process by which non-coding introns are removed from precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) and coding exons are joined together. This process is executed by the spliceosome, a dynamic ribonucleoprotein complex composed of five small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) and numerous associated proteins [16]. The spliceosome recognizes conserved sequence motifs at exon-intron boundaries and carries out a two-step transesterification reaction to remove introns and ligate exons [16]. Recent cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies have yielded high-resolution structures of several conformational states of the spliceosome, revealing the dynamic rearrangements that drive intron removal and exon ligation [16].

The timing of splicing relative to transcription has substantial impact on gene expression outcomes. Splicing can occur either co-transcriptionally, as the pre-mRNA is being synthesized, or post-transcriptionally, after transcription is completed [16] [19]. Recent advances in long-read sequencing and imaging methods have provided insights into the timing and regulation of splicing, revealing its dynamic interplay with transcription and RNA processing [16]. Notably, recent analyses have revealed that up to 40% of mammalian introns are retained after transcription termination and are subsequently removed largely while transcripts remain chromatin-associated [19].

Alternative Splicing and Regulatory Mechanisms

Alternative splicing greatly expands the coding potential of the genome; more than 95% of human multi-intron genes undergo alternative splicing, producing mRNA isoforms that can differ in coding sequence, regulatory elements, or untranslated regions [16]. These isoforms can influence mRNA stability, localization, and translation output, thereby modulating cellular function [16]. There are seven major types of alternative splicing events: exon skipping, alternative 3' splice sites, alternative 5' splice sites, intron retention, mutually exclusive exons, alternative first exons, and alternative last exons [20].

Table: Major Types of Alternative Splicing Events

| Splicing Type | Description | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Exon Skipping | An exon is spliced out of the transcript | Can remove protein domains or regulatory regions |

| Alternative 3' Splice Sites | Selection of different 3' splice sites | Can alter C-terminal protein sequences |

| Alternative 5' Splice Sites | Selection of different 5' splice sites | Can alter N-terminal protein sequences |

| Intron Retention | An intron remains in the mature transcript | May introduce premature stop codons or alter reading frames |

| Mutually Exclusive Exons | One of two exons is selected, but not both | Can swap functionally distinct protein domains |

| Alternative First Exons | Selection of different transcription start sites | Can alter promoters and N-terminal coding sequences |

| Alternative Last Exons | Selection of different transcription end sites | Can alter C-terminal coding sequences and 3'UTRs |

Recent research has uncovered novel regulatory mechanisms controlling splicing decisions. MIT biologists recently discovered that a family of proteins called LUC7 helps determine whether splicing will occur for approximately 50% of human introns [21]. The research team found that two LUC7 proteins interact specifically with one type of 5' splice site ("right-handed"), while a third LUC7 protein interacts with a different type ("left-handed") [21]. This regulatory system adds another layer of complexity that helps remove specific introns more efficiently and allows for more complex types of gene regulation [21].

Experimental Approaches for Splicing Analysis

The advent of high-throughput RNA sequencing has revolutionized the ability to detect transcriptome-wide splicing events. Both bulk RNA-seq and single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) enable high-resolution profiling of transcriptomes, uncovering the complexity of RNA processing at both population and single-cell levels [20]. Computational methods have been developed to identify and quantify alternative splicing events, with specialized tools designed for different data types and experimental questions.

Table: Computational Methods for Splicing Analysis

| Method Category | Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-seq Analysis | Roar, rMATS, MAJIQ | Identify differential splicing between conditions |

| Single-cell Analysis | Sierra, BAST | Resolve splicing heterogeneity at single-cell level |

| de novo Transcript Assembly | Cufflinks, StringTie | Reconstruct transcripts without reference annotation |

| Splicing Code Models | various deep learning approaches | Predict splicing patterns from sequence features |

For researchers investigating splicing mechanisms, several key experimental protocols provide insights into splicing regulation:

Protocol 1: Analysis of Splicing Kinetics Using Metabolic Labeling

- Incubate cells with 4-thiouridine (4sU) or 5-ethynyluridine (5-EU) to label newly transcribed RNA

- Harvest RNA at multiple time points after labeling (e.g., 15min, 30min, 1h, 2h, 4h)

- Separate labeled (new) from unlabeled (pre-existing) RNA using biotin conjugation and streptavidin pulldown

- Prepare sequencing libraries from both fractions

- Map sequencing reads to reference genome and quantify intron retention levels

- Calculate splicing kinetics based on appearance of spliced isoforms in labeled fraction over time [19]

Protocol 2: Splicing-Focused CRISPR Screening

- Design sgRNA library targeting splicing factors, RNA-binding proteins, and regulatory elements

- Transduce cells with lentiviral sgRNA library at low MOI to ensure single integration events

- Apply selective pressure or specific cellular stressors relevant to research question

- Harvest genomic DNA at multiple time points

- Amplify sgRNA regions and sequence with high coverage

- Identify enriched/depleted sgRNAs using specialized analysis tools (e.g., MAGeCK)

- Validate hits using individual sgRNAs and RT-PCR splicing assays [21]

RNA Editing: Mechanisms and Functions

Types and Mechanisms of RNA Editing

RNA editing encompasses biochemical processes that alter the RNA sequence relative to the DNA template. The most common type of RNA editing in mammals is adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) editing, catalyzed by adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) enzymes [17]. Inosine is interpreted as guanosine by cellular machinery, effectively resulting in A-to-G changes in the RNA sequence. This process can alter coding potential, splice sites, microRNA target sites, and secondary structures of RNAs [18].

Another significant editing mechanism is cytosine-to-uracil (C-to-U) editing, mediated by the APOBEC family of enzymes, though this is less common in mammals than A-to-I editing [17]. In plants, C-to-U editing directed by pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins contributes to environmental adaptability [17].

Biological Roles and Disease Associations

RNA editing serves diverse biological functions, including regulation of neurotransmitter receptor function, modulation of immune responses, and maintenance of cellular homeostasis [17]. Recent comprehensive analyses have revealed the importance of RNA editing in human diseases, particularly neurological disorders. A 2025 study characterized the RNA editing landscape in the human aging brains with Alzheimer's disease, identifying 127 genes with significant RNA editing loci [18]. The study found that Alzheimer's disease exhibits elevated RNA editing in specific brain regions (parahippocampal gyrus and cerebellar cortex) and discovered 147 colocalized genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and cis-edQTL signals in 48 likely causal genes including CLU, BIN1, and GRIN3B [18]. These findings suggest that RNA editing plays a crucial role in Alzheimer's pathophysiology, primarily allied to amyloid and tau pathology, and neuroinflammation [18].

Experimental Approaches for Editing Analysis

Protocol 3: Genome-Wide RNA Editing Detection

- Isolate high-quality RNA and DNA from the same tissue or cell sample

- Perform paired-end RNA sequencing (≥100M reads) and whole-genome sequencing (≥30x coverage)

- Align RNA-seq reads to reference genome using splice-aware aligners (e.g., STAR)

- Identify potential editing sites using variant callers specialized for RNA editing (e.g., REDItools, JACUSA)

- Filter sites against common SNPs (using dbSNP and matched DNA-seq data)

- Remove sites with potential mapping biases or alignment artifacts

- Annotate remaining high-confidence editing sites with genomic features

- Perform differential editing analysis between conditions using statistical methods (e.g., beta-binomial tests) [18]

Protocol 4: Targeted RNA Editing Using CRISPR-Based Systems

- Design guide RNAs targeting specific adenosine residues for A-to-I editing

- Clone guide RNA sequences into appropriate expression vectors

- Co-transfect cells with vectors expressing:

- Catalytically inactive Cas13 (dCas13) fused to ADAR deaminase domain (for REPAIR system)

- Or engineer endogenous ADAR enzymes using circular RNAs (LEAPER 2.0 technology)

- Include appropriate nuclear localization signals for targeting nuclear transcripts

- Harvest RNA 48-72 hours post-transfection

- Analyze editing efficiency by RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing or amplicon sequencing

- Validate functional consequences through Western blot or functional assays [17]

RNA Editing Mechanism and Consequences

Integration with Other RNA Maturation Processes

Connections with Alternative Polyadenylation

RNA splicing coordinates with other RNA maturation processes, particularly alternative polyadenylation (APA). APA modifies transcript stability, localization, and translation efficiency by generating mRNA isoforms with distinct 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) or coding sequences [20]. There are two primary types of APA: 3'-UTR APA (UTR-APA), which generates mRNAs with truncated 3' UTRs and typically promotes protein synthesis, and intronic APA (IPA), which occurs within a gene's intron and results in mRNA truncation within the coding region [20]. Approximately 50% (~12,500 genes) of annotated human genes harbor at least one IPA event [20].

The integration of splicing and polyadenylation decisions creates complex regulatory networks that expand transcriptome diversity. Computational methods have been developed to jointly analyze these processes, with tools like APAtrap, TAPAS, and APAlyzer capable of detecting both UTR-APA and IPA events from RNA-seq data [20].

RNA Modification Landscapes

Beyond editing, RNAs undergo numerous chemical modifications that constitute the "epitranscriptome." The most frequent RNA epitranscriptomic marks are methylations either on RNA bases or on the 2'-OH group of the ribose, catalyzed mainly by S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferases (MTases) [22]. TRMT112 is a small protein acting as an allosteric regulator of several MTases, serving as a master activator of methyltransferases that modify factors involved in RNA maturation and translation [22]. Growing evidence supports the importance of these MTases in cancer and correct brain development [22].

Protocol 5: Transcriptome-Wide Mapping of RNA Modifications

- Isolate RNA under conditions that preserve modifications (avoid harsh purification methods)

- For m⁶A mapping: Perform immunoprecipitation with anti-m⁶A antibodies (meRIP-seq)

- Alternatively, use antibody-independent methods such as Mazter-seq or DART-seq

- For pseudouridine mapping: Use CMC modification followed by reverse transcription

- Sequence enriched fractions and input controls

- Call modification peaks using specialized peak-calling algorithms

- Integrate with splicing and expression data to identify coordinated regulation

- Validate key findings using mass spectrometry or site-specific assays [22]

Therapeutic Targeting and Future Directions

RNA-Targeted Therapeutics

RNA splicing and editing have emerged as promising therapeutic targets for various diseases. Targeting RNA splicing with therapeutics, such as antisense oligonucleotides or small molecules, has become a powerful and increasingly validated strategy to treat genetic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and certain cancers [16] [17]. Splicing modulation has emerged as the most clinically validated strategy, exemplified by FDA-approved drugs like risdiplam for spinal muscular atrophy [23].

RNA-targeting small molecules represent a transformative frontier in drug discovery, offering novel therapeutic avenues for diseases traditionally deemed undruggable [23]. Recent advances include the development of RNA degraders and modulators of RNA-protein interactions, expanding the toolkit for therapeutic intervention [23]. As of 2025, RNA editing therapeutics have entered clinical trials, with Wave Therapeutics announcing positive proof-of-mechanism data for their RNA editing platform [24].

Technological Advances

Technological innovations continue to drive discoveries in RNA biology. Machine learning models are improving our ability to predict the effects of genetic variants on splicing, with the potential to guide drug development and clinical diagnostics [16]. Computational approaches that integrate with experimental validation are increasingly critical for advancing RNA-targeted therapeutics [23].

The field of RNA structure determination has seen significant advances, with methods ranging from X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [23]. Computational prediction of RNA structures has recently emerged as a complementary approach, with machine learning algorithms now capable of predicting secondary and tertiary structures with remarkable accuracy [23].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Processing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Splicing Modulators | Risdiplam, Branaplam | Small molecules that modulate splice site selection |

| CRISPR-Based Editing Tools | REPAIR system, LEAPER 2.0 | Precision RNA editing using dCas13-ADAR fusions or endogenous ADAR recruitment |

| Metabolic Labeling Reagents | 4-thiouridine (4sU), 5-ethynyluridine (5-EU) | Pulse-chase analysis of RNA processing kinetics |

| Computational Tools | QAPA, APAtrap, MAJIQ, REDItools | Detection and quantification of splicing, polyadenylation, and editing events |

| Antibodies for RNA Modifications | anti-m⁶A, anti-m⁵C, anti-Ψ | Immunoprecipitation-based mapping of epitranscriptomic marks |

| Library Preparation Kits | SMARTer smRNA-seq, DIRECT-RNA | Specialized protocols for sequencing different RNA fractions |

Therapeutic Approaches Targeting RNA Processing

The processes of RNA splicing, editing, and maturation represent central layers of gene regulation that expand genomic coding potential and enable precise control over gene expression outputs. Once considered mere intermediate steps between transcription and translation, these processes are now recognized as sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that contribute to normal development, cellular homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis when dysregulated. Advances in sequencing technologies, structural biology, and computational methods have revealed unprecedented complexity in these post-transcriptional regulatory networks. The growing understanding of these mechanisms has opened new therapeutic avenues, with RNA-targeted therapies emerging as promising treatments for previously untreatable conditions. As research continues to decipher the intricate relationships between splicing, editing, and other RNA maturation processes, and as technologies for measuring and manipulating these processes evolve, our ability to understand and therapeutically modulate gene expression will continue to expand, reshaping both basic biological understanding and clinical practice.

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) represent a crucial regulatory layer that expands the functional diversity of the proteome and serves as a fundamental mechanism governing gene expression and cellular physiology. This technical review provides an in-depth analysis of three central PTMs—phosphorylation, glycosylation, and ubiquitination—focusing on their molecular mechanisms, regulatory functions in signal transduction, and experimental methodologies for their investigation. Within the framework of gene expression regulation, we examine how these PTMs precisely control transcription factor activity, mRNA stability, and protein turnover, thereby enabling cells to dynamically respond to environmental cues and maintain homeostasis. The content is structured to equip researchers with both theoretical knowledge and practical experimental approaches, including detailed protocols, reagent solutions, and data visualization tools, to advance investigation in this rapidly evolving field.

The human proteome's complexity vastly exceeds that of the genome, with an estimated 1 million proteins compared to approximately 20,000-25,000 genes [25]. This diversity arises substantially through post-translational modifications (PTMs), covalent alterations to proteins that occur after translation. PTMs regulate virtually all aspects of normal cell biology and pathogenesis by influencing protein activity, localization, stability, and interactions with other cellular molecules [25]. As a cornerstone of functional proteomics, PTMs represent a critical interface between cellular signaling and gene expression outcomes, enabling precise spatiotemporal control of physiological processes.

In the specific context of gene expression regulation, PTMs serve as key mechanistic links that translate extracellular signals into altered transcriptional programs and protein abundance. Transcription factors, the direct gatekeepers of gene expression, are themselves heavily modified by PTMs that orchestrate their entire functional lifespan—from subcellular localization and DNA-binding affinity to protein-protein interactions and stability [26]. Beyond transcription, PTMs directly regulate mRNA processing, stability, and translation, adding further layers of control to gene expression outputs. This review focuses on phosphorylation, glycosylation, and ubiquitination as three central PTMs that exemplify the sophisticated regulatory capacity of protein modifications in shaping cellular responses through gene regulatory networks.

Phosphorylation

Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Functions

Protein phosphorylation, the reversible addition of a phosphate group to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues, constitutes one of the most extensively studied PTMs [25]. This modification is catalyzed by kinases and reversed by phosphatases, creating dynamic regulatory switches that control numerous cellular processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and signal transduction pathways [25]. The negative charge introduced by phosphorylation can induce conformational changes that alter protein function, create docking sites for protein interactions, or regulate catalytic activity.

In gene expression regulation, phosphorylation exerts multifaceted control over transcription factors. It can regulate transcription factor stability, subcellular localization, DNA-binding affinity, and transcriptional activation capacity [26]. Multiple phosphorylation sites within a single transcription factor can function as coincidence detectors, tunable signal regulators, or cooperative signaling response elements. For instance, the MSN2 transcription factor in yeast processes different stress responses through "tunable" nuclear accumulation governed by phosphorylation at eight serine residues within distinct regulatory domains, generating differentially tuned responses to various stressors [26].

A recently elucidated mechanism demonstrates phosphorylation-dependent tuning of mRNA deadenylation rates, directly connecting this PTM to post-transcriptional regulation. Phosphorylation modulates interactions between the intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of RNA adaptors like Puf3 and the Ccr4-Not deadenylase complex, altering deadenylation kinetics in a continuously tunable manner rather than as a simple binary switch [27]. This graded mechanism enables fine-tuning of post-transcriptional gene expression through phosphorylation-dependent regulation of mRNA decay.

Experimental Methods and Reagent Solutions

Western blot analysis using phospho-specific antibodies represents a cornerstone technique for investigating protein phosphorylation. The Thermo Scientific Pierce Phosphoprotein Enrichment Kit enables highly pure phosphoprotein enrichment from complex biological samples, as validated through experiments with serum-starved HeLa and NIH/3T3 cell lines stimulated with epidermal growth factor (EGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), respectively [25]. Critical controls in such experiments include cytochrome C (pI 9.6) and p15Ink4b (pI 5.5) as negative controls for nonspecific binding of non-phosphorylated proteins [25].

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Phosphorylation Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Specific Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Recognize phosphorylated amino acid residues | Western blot detection of specific phosphoproteins |

| Pierce Phosphoprotein Enrichment Kit | Enriches phosphorylated proteins from complex lysates | Reduction of sample complexity prior to phosphoprotein analysis |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent undesired dephosphorylation during lysis | Preservation of endogenous phosphorylation states |

| Kinase Assay Kits | Measure kinase activity in vitro | Screening kinase inhibitors or characterizing kinase substrates |

Figure 1: Phosphorylation-Dependent Gene Regulation. Extracellular signals trigger kinase cascades that phosphorylate transcription factors, influencing their nuclear localization and ability to regulate target gene expression.

Glycosylation

Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Functions

Glycosylation involves the enzymatic addition of carbohydrate structures to proteins and is one of the most prevalent and complex PTMs [28]. The two primary forms are N-linked glycosylation (attachment to asparagine residues) and O-linked glycosylation (attachment to serine or threonine residues) [25]. Glycosylation significantly influences protein folding, conformation, distribution, stability, and activity [25] [28]. The process begins in the endoplasmic reticulum and continues in the Golgi apparatus, involving numerous glycosyltransferases and glycosidases that generate remarkable structural diversity [28].

In gene regulation, glycosylation modulates transcription factor activity through several mechanisms. O-GlcNAcylation, the addition of β-D-N-acetylglucosamine to serine/threonine residues, occurs on numerous transcription factors and transcriptional regulatory proteins, with effects ranging from protein stabilization to inhibition of transcriptional activation [26]. This modification competes with phosphorylation at the same or adjacent sites, creating reciprocal regulatory switches that integrate metabolic information into gene regulatory programs. The enzymes responsible for O-GlcNAcylation—O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA)—respond to nutrient availability (glucose), insulin, and cellular stress, positioning this PTM as a key sensor linking metabolic status to gene expression [26].

Emerging evidence reveals novel roles for glycosylation in epitranscriptomic regulation. Recent research has identified 5'-terminal glycosylation of protein-coding transcripts in Escherichia coli, where glucose caps on U-initiated mRNAs prolong transcript lifetime by impeding 5'-end-dependent degradation [29]. This previously unrecognized form of epitranscriptomic modification expands the functional repertoire of glycosylation in gene expression regulation and may selectively enhance synthesis of proteins encoded by U-initiated transcripts.

Experimental Methods and Reagent Solutions

Multiple methodological approaches are required to comprehensively analyze protein glycosylation due to its structural complexity. Mass spectrometry-based glycomics and glycoproteomics enable system-wide characterization of glycan structures and their attachment sites. The biotin switch assay, originally developed for detecting S-nitrosylation, has been adapted for various PTM studies and can be modified for glycosylation investigation [25]. Lectin-based affinity enrichment provides a complementary approach for isolating specific glycoforms prior to analytical separation.

Table 2: Glycosylation Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent/Method | Principle | Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Lectin Affinity Columns | Carbohydrate-binding proteins isolate glycoproteins | Enrichment of specific glycoforms from complex mixtures |

| Glycosidase Enzymes | Enzymatic removal of specific glycan structures | Characterization of glycosylation type and complexity |

| Metabolic Labeling with Sugar Analogs | Incorporation of modified sugars into glycoconjugates | Detection, identification and tracking of newly synthesized glycoproteins |

| Anti-Glycan Antibodies | Immunorecognition of specific carbohydrate epitopes | Western blot, immunohistochemistry, and flow cytometry applications |

Figure 2: O-GlcNAcylation in Gene Regulation. Nutrient status influences UDP-GlcNAc availability through the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, modulating transcription factor O-GlcNAcylation via the opposing actions of OGT and OGA, ultimately affecting gene expression.

Ubiquitination

Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Functions

Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid polypeptide, to lysine residues on target proteins [25]. This process occurs through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ubiquitin ligases that confer substrate specificity [30]. Following initial monoubiquitination, subsequent ubiquitin molecules can form polyubiquitin chains with distinct functional consequences depending on the linkage type. While K48-linked ubiquitin chains typically target proteins for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked chains primarily regulate signal transduction, protein trafficking, and DNA repair [31] [30].

In gene expression regulation, ubiquitination controls the stability and activity of numerous transcription factors and core clock proteins. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) ensures precise temporal degradation of transcriptional regulators, enabling dynamic gene expression patterns in processes such as circadian rhythms [30]. Core clock proteins like PERIOD and CRYPTOCHROME undergo ubiquitin-mediated degradation at specific times within the circadian cycle, which is essential for maintaining proper oscillation and resetting the molecular clock [30].

Beyond protein degradation, ubiquitination activates specific signaling cascades that directly impact gene expression. Recent research has elucidated a ubiquitination-activated TAB-TAK1-IKK-NF-κB axis that modulates gene expression for cell survival in the lysosomal damage response [31]. K63-linked ubiquitin chains accumulating on damaged lysosomes activate this signaling pathway, leading to expression of transcription factors and cytokines that promote anti-apoptosis and intercellular communication [31]. This mechanism demonstrates how ubiquitination serves as a critical signaling platform coordinating organelle homeostasis with gene expression programs.

Experimental Methods and Reagent Solutions

The Thermo Scientific Pierce Ubiquitin Enrichment Kit provides effective isolation of ubiquitinated proteins from complex cell lysates, as demonstrated in comparative studies with HeLa cell lysates where it yielded superior enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins compared to alternative methods [25]. Western blot analysis remains a fundamental detection method, while mass spectrometry-based proteomics enables system-wide identification of ubiquitination sites and linkage types. Dominant-negative ubiquitin mutants (e.g., K48R or K63R) help determine the functional consequences of specific ubiquitin linkages.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent/Assay | Mechanism | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Kits | Affinity-based purification of ubiquitinated proteins | Isolation of ubiquitinated proteins prior to detection or analysis |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Block proteasomal degradation | Stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins to enhance detection |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Prevent removal of ubiquitin chains | Preservation of endogenous ubiquitination states |

| Ubiquitin Variant Sensors | Selective recognition of specific ubiquitin linkages | Determination of polyubiquitin chain topology in cells |

Figure 3: Ubiquitination in Gene Regulation. The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade conjugates ubiquitin to target proteins. Polyubiquitination can target transcription factors for proteasomal degradation or activate signaling pathways, both leading to altered gene expression.

Interconnected PTMs in Gene Regulatory Networks

Cross-Regulation and Hierarchical Modifications

PTMs rarely function in isolation; rather, they form intricate networks of interdependent modifications that collectively determine protein function. These interconnected PTMs can occur as sequential events where one modification promotes or inhibits the establishment of another modification within the same protein [26]. This phenomenon, often described as "PTM crosstalk," enables sophisticated signal integration and fine-tuning of transcriptional responses.

A prominent example of PTM crosstalk in gene regulation is the reciprocal relationship between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation. These modifications frequently target the same or adjacent serine/threonine residues, creating molecular switches that integrate metabolic information with signaling pathways [26]. The enzymes governing these modifications themselves undergo reciprocal regulation—kinases are overrepresented among O-GlcNAcylation substrates, while O-GlcNAc transferase is phosphoactivated by kinases that are themselves regulated by O-GlcNAcylation [26]. This creates complex regulatory circuits that enable precise tuning of transcriptional responses to changing cellular conditions.

The functional consequences of interconnected PTMs are exemplified by the regulation of transcription factor stability. Multisite phosphorylation can create degradation signals (degrons) that promote subsequent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of transcription factors like ATF4, allowing dose-dependent regulation of target genes in processes such as neurogenesis [26]. Similarly, phosphorylation of the PERIOD clock protein creates binding sites for E3 ubiquitin ligases, linking the circadian timing mechanism to controlled protein turnover [30].

Experimental Approaches for Studying PTM Crosstalk

Investigating interconnected PTMs requires methodological approaches capable of capturing multiple modification types simultaneously. Advanced mass spectrometry-based proteomics now enables system-wide profiling of various PTMs, revealing co-occurrence patterns and potential regulatory hierarchies. The PTMcode database (http://ptmcode.embl.de) provides a valuable resource for exploring sequentially linked PTMs in proteins [26]. Functional validation typically involves mutagenesis of modification sites combined with pharmacological inhibition of specific modifying enzymes to dissect hierarchical relationships.

Concluding Perspectives and Therapeutic Implications

The pervasive influence of phosphorylation, glycosylation, and ubiquitination on gene regulation extends to numerous pathological conditions, making these PTMs attractive therapeutic targets. In cancer immunotherapy, PTMs extensively regulate immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1, CTLA-4, and others, influencing immunotherapy efficacy and treatment resistance [32]. Targeting the PTMs of these checkpoints represents a promising strategy for improving cancer immunotherapy outcomes.

The expanding toolkit for investigating PTMs includes increasingly sophisticated chemical biology approaches. For glycosylation studies, temporary glycosylation scaffold strategies offer reversible approaches to guide protein folding without permanent modifications, holding significant potential for producing therapeutic proteins and developing synthetic proteins with precise structural requirements [33]. Similarly, small molecules that modulate ubiquitin-mediated degradation of core clock proteins offer potential strategies for resetting circadian clocks disrupted in various disorders [30].

Future research directions will likely focus on developing technologies capable of capturing the dynamic, combinatorial nature of PTM networks in living cells and understanding how specific patterns of modifications generate distinct functional outputs. As our knowledge of the PTM "code" deepens, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention in the myriad diseases characterized by dysregulated gene expression, from cancer to metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders.

Epigenetic regulation provides a critical layer of control over gene expression programs without altering the underlying DNA sequence, serving as a fundamental interface between the genome and cellular environment. This regulatory domain works synergistically with DNA-encoded information to support essential biological processes including phenotypic determination, proliferation, growth control, metabolic regulation, and cell survival [34]. Within this framework, two interconnected mechanisms—DNA methylation and chromatin remodeling—stand as pillars of epigenetic control. DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, predominantly at CpG dinucleotides, leading to transcriptional repression through chromatin compaction and obstruction of transcription factor binding [35]. Chromatin remodeling, an ATP-dependent process, dynamically reconfigures nucleosome positioning and composition through enzymatic complexes that slide, evict, or restructure nucleosomes [36]. Together, these systems establish and maintain cell-type-specific gene expression patterns that define cellular identity and function. The intricate interplay between these epigenetic layers enables precise spatiotemporal control of genomic information, with profound implications for development, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic interventions.

DNA Methylation: Mechanisms and Biological Functions

Molecular Machinery of DNA Methylation

DNA methylation represents a fundamental epigenetic mark involving the covalent transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the fifth carbon of cytosine residues, primarily within CpG dinucleotides [35]. This reaction is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which constitute a family of enzymes with specialized functions. The DNMT family includes DNMT1, responsible for maintaining methylation patterns during DNA replication by recognizing hemi-methylated sites, and the de novo methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B, which establish new methylation patterns during embryonic development and cellular differentiation [35]. DNMT3L, a catalytically inactive cofactor, enhances the activity of DNMT3A/B, while DNMT3C, found specifically in male germ cells, ensures meiotic silencing [35].

The distribution of DNA methylation across the genome is non-random, with approximately 70-90% of CpG sites methylated in mammalian cells [35]. CpG islands—genomic regions with high G+C content and dense CpG clustering—remain largely unmethylated, particularly when located near promoter regions or transcriptional start sites. This distribution reflects the dual functionality of DNA methylation in transcriptional regulation: promoter methylation typically suppresses gene expression, while gene body methylation exhibits more complex regulatory roles including facilitation of transcription elongation and alternative splicing [37].

The reading and interpretation of DNA methylation marks is mediated by methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MBDs), including MBD1-4 and MeCP2 [35]. These proteins recognize methylated DNA and recruit additional complexes containing histone deacetylases (HDACs) and other chromatin modifiers, establishing a repressive chromatin state. This connection demonstrates the functional integration between DNA methylation and histone modifications in gene silencing.

DNA demethylation occurs through both passive and active mechanisms. Passive demethylation involves the dilution of methylation marks during DNA replication in the absence of DNMT1 activity. Active demethylation is catalyzed by Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) enzymes, which iteratively oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), ultimately leading to base excision repair and replacement with an unmodified cytosine [35] [38].

Metabolic Regulation of DNA Methylation

The DNA methylation process is intrinsically linked to cellular metabolism, with key metabolites serving as essential cofactors and substrates. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) functions as the universal methyl donor for DNMTs and histone methyltransferases, directly linking one-carbon metabolism to epigenetic regulation [38]. SAM production depends on methionine availability and folate cycle activity, creating a direct conduit through which nutritional status influences the epigenome. Following methyl group transfer, SAM is converted to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), a potent competitive inhibitor of DNMTs and histone methyltransferases. The SAM:SAH ratio therefore serves as a critical metabolic indicator of cellular methylation capacity [38].

In cancer cells, metabolic reprogramming frequently upregulates one-carbon metabolism to support rapid proliferation, resulting in elevated SAM levels that drive hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes [38]. Conversely, SAM depletion can lead to DNA hypomethylation and oncogene activation. This metabolic-epigenetic nexus extends to therapeutic applications, as demonstrated in gastric cancer where SAM treatment induced hypermethylation of the VEGF-C promoter, suppressing its expression and inhibiting tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo [38].

DNA Methylation in Development and Disease

DNA methylation undergoes dynamic reprogramming during embryonic development and gametogenesis. In mammalian primordial germ cells, genome-wide DNA demethylation occurs, erasing most methylation marks, including those at imprinted loci [35]. This is followed by de novo methylation during prospermatogonial development, establishing sex-specific methylation patterns [35]. Similarly, during spermatogenesis, DNA methylation levels fluctuate dynamically, with increasing methylation during the transition from undifferentiated spermatogonia to differentiating spermatogonia, followed by demethylation in preleptotene spermatocytes and subsequent remethylation during meiotic stages [35].

Dysregulation of DNA methylation patterns is implicated in various pathologies, including male infertility and cancer. Comparative analyses of testicular biopsies from patients with obstructive azoospermia (OA) and non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) reveal differential DNMT expression profiles, underscoring the importance of proper methylation control for normal spermatogenesis [35]. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), sophisticated computational approaches like Methylation Signature Analysis with Independent Component Analysis (MethICA) have identified distinct methylation signatures associated with specific driver mutations, including CTNNB1 mutations and ARID1A alterations [39]. These signatures provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying hepatocarcinogenesis and highlight the potential of methylation patterns as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers.

Chromatin Remodeling: Complex Composition and Biological Functions

ATP-Dependent Chromatin Remodeling Complexes

Chromatin remodeling represents an ATP-dependent process mediated by specialized enzymes that alter histone-DNA interactions, thereby modulating chromatin accessibility and functionality. These remodelers utilize energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to catalyze nucleosome sliding, eviction, assembly, and histone variant exchange [36]. Based on sequence homology and functional characteristics, chromatin remodelers are classified into several major families, each with distinct mechanistic properties and biological functions.

The SWI/SNF (Switching Defective/Sucrose Non-Fermenting) family remodelers facilitate chromatin opening through nucleosome sliding, histone octamer eviction, and dimer displacement, primarily promoting transcriptional activation [36]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the SWI/SNF subfamily includes four ATPase chromatin remodelers: BRM, SYD, MINU1, and MINU2, with BRM exhibiting conserved domains similar to yeast and mammalian counterparts, while SYD and MINU1/2 display plant-specific domain organization [36].

The ISWI (Imitation SWI) and CHD (Chromodomain Helicase DNA-binding) families specialize in nucleosome assembly and spacing, utilizing DNA-binding domains that function as molecular rulers to measure linker DNA segments between nucleosomes [36]. This spacing function is crucial for establishing regular nucleosome arrays and maintaining chromatin structure.

The INO80 (Inositol-requiring protein 80) and SWR1 (SWI2/SNF2-Related 1) families mediate nucleosome editing through incorporation or exclusion of histone variants, particularly the H2A variant H2A.Z [36]. While SWR1 specifically replaces H2A-H2B dimers with H2A.Z-H2B variants, INO80 exhibits broader functionality including nucleosome sliding and both eviction and deposition of H2A.Z-H2B dimers [36]. In Arabidopsis, ISWI remodelers CHR11 and CHR17 can function as components of the SWR1 complex, illustrating a plant-specific mechanism that couples nucleosome positioning with H2A.Z deposition [36].

Several additional SNF2-family chromatin remodelers, including DDM1 (Decrease in DNA Methylation 1), DRD1 (Defective in Meristem Silencing 1), and CLASSYs, regulate DNA methylation and transcriptional silencing in plants [36]. These specialized remodelers highlight the functional integration between nucleosome positioning and DNA methylation in epigenetic regulation.

Chromatin Remodeling in Transcriptional Regulation and Development

Chromatin remodeling complexes play pivotal roles in diverse biological processes including transcriptional regulation, DNA replication, DNA damage repair, and the establishment of epigenetic marks. By modulating chromatin accessibility, these complexes govern the precise spatiotemporal patterns of gene expression that guide developmental programs and cellular differentiation.

In plants, which as sessile organisms must adapt to fluctuating environmental conditions, chromatin remodeling has evolved unique regulatory specializations that enable response to ecological challenges [36]. Forward genetic screens in Arabidopsis thaliana have revealed that CLASSY proteins regulate DNA methylation patterns, with recent research identifying RIM proteins (REPRODUCTIVE MERISTEM transcription factors) that collaborate with CLASSY3 to establish DNA methylation at specific genomic targets in reproductive tissues [40]. This discovery represents a paradigm shift in understanding methylation regulation, revealing that genetic sequences—not just pre-existing epigenetic marks—can direct new methylation patterns [40].

The compositional complexity of chromatin remodeling complexes contributes to their functional diversity. In mammals, SWI/SNF remodelers form three distinct subcomplexes—cBAF (canonical BRG1/BRM-associated factor), pBAF (polybromo-associated BAF), and ncBAF (non-canonical BAF)—each with specialized roles in gene regulation [36]. Similarly, Drosophila possesses two SWI/SNF subcomplexes (BAP and PBAP), while yeast contains SWI/SNF and RSC complexes. Recent advances in proteomics and biochemical characterization have enabled comprehensive identification of plant SWI/SNF complex subunits, revealing both conserved and plant-specific components [36].

Experimental Approaches for Epigenetic Analysis

DNA Methylation Profiling Technologies

Accurate assessment of DNA methylation patterns is essential for understanding its functional significance in development and disease. Multiple technologies have been developed for genome-wide methylation profiling, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applications. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of major DNA methylation detection methods:

Table 1: Comparison of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiling Methods

| Method | Resolution | Genomic Coverage | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina EPIC Array | Single CpG site | ~935,000 CpG sites [37] | Cost-effective, standardized processing, high throughput [37] | Limited to predefined CpG sites, bias toward gene regulatory regions [37] |

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | ~80% of CpG sites [37] | Comprehensive coverage, reveals sequence context, absolute methylation levels [37] | DNA degradation from bisulfite treatment, high computational requirements [37] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Single-base | Comparable to WGBS [37] | Preserves DNA integrity, reduces sequencing bias, improved CpG detection [37] | Newer method with less established analytical pipelines |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) | Single-base | Long contiguous regions | Long-read sequencing, detects methylation in challenging regions, no conversion needed [37] | High DNA input requirements, lower agreement with bisulfite-based methods [37] |

Bisulfite conversion-based methods remain widely used, with the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip array assessing over 935,000 methylation sites covering 99% of RefSeq genes [37]. This technology provides a balanced approach for large-scale epidemiological studies, though it is limited to predefined CpG sites. WGBS offers truly comprehensive coverage but involves substantial DNA degradation due to harsh bisulfite treatment conditions, which can introduce artifacts through incomplete cytosine conversion [37].

Emerging technologies address these limitations through alternative approaches. EM-seq utilizes TET2 enzyme-mediated conversion combined with APOBEC deamination to detect methylation states while preserving DNA integrity [37]. This method demonstrates high concordance with WGBS while reducing sequencing bias. Oxford Nanopore Technologies enables direct detection of DNA methylation without chemical conversion or enzymatic treatment, instead relying on electrical signal deviations as DNA passes through protein nanopores [37]. This approach facilitates long-read sequencing that can resolve complex genomic regions and haplotypes.

Table 2: Practical Considerations for DNA Methylation Method Selection

| Parameter | EPIC Array | WGBS | EM-seq | ONT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Input | 500 ng [37] | 1 μg [37] | Lower input possible [37] | ~1 μg of 8 kb fragments [37] |