Evaluating the Efficiency of Gene Silencing Oligonucleotides: A Comprehensive Guide for Therapeutic Development

This article provides a critical evaluation of the efficiency of different gene silencing oligonucleotides, including ASOs, siRNAs, and miRNAs, for researchers and drug development professionals.

Evaluating the Efficiency of Gene Silencing Oligonucleotides: A Comprehensive Guide for Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a critical evaluation of the efficiency of different gene silencing oligonucleotides, including ASOs, siRNAs, and miRNAs, for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores foundational mechanisms, from RNase H-dependent degradation to RNA interference (RNAi). The content details methodological applications across disease areas like oncology and neurology, addresses key challenges in delivery and stability, and offers a comparative analysis of silencing strategies against emerging gene-editing tools. Supported by recent advances in nanotechnology and conjugate systems, this review serves as a strategic resource for selecting, optimizing, and validating oligonucleotide-based therapies to overcome historical barriers in clinical translation.

Core Mechanisms of Gene Silencing: From ASOs to RNAi

Gene silencing is a fundamental biological process for regulating gene expression, enabling researchers and drug developers to precisely inhibit the function of specific genes. This capability is crucial for functional genomics, drug discovery, and therapeutic development. The two primary mechanisms—transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) and post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS)—operate at distinct stages of the central dogma and employ different molecular machinery. TGS prevents RNA synthesis at the DNA level through epigenetic modifications, while PTGS degrades or blocks already synthesized mRNA molecules, preventing translation into protein [1]. Understanding these differences is essential for selecting the optimal gene silencing strategy for specific research or therapeutic objectives. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these mechanisms, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to oligonucleotide-based research.

The following table outlines the fundamental characteristics of TGS and PTGS, highlighting their distinct operational stages, key effectors, and primary outcomes.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Transcriptional vs. Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing

| Feature | Transcriptional Gene Silencing (TGS) | Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing (PTGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage of Action | Transcription initiation (DNA level) [1] | After transcription (mRNA level) [1] |

| Primary Target | Gene promoter region [1] | Messenger RNA (mRNA) transcript [1] |

| Molecular Triggers | dsRNA homologous to promoter sequences, DNA methylation, histone modifications [1] | dsRNA homologous to coding sequences, RNA interference (RNAi) [1] |

| Key Epigenetic Mark | Promoter DNA methylation [1] | Not typically involved |

| Primary Outcome | Inhibition of RNA synthesis [1] | Sequence-specific degradation of mRNA [1] |

Molecular Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Pathway of dsRNA-Induced Gene Silencing

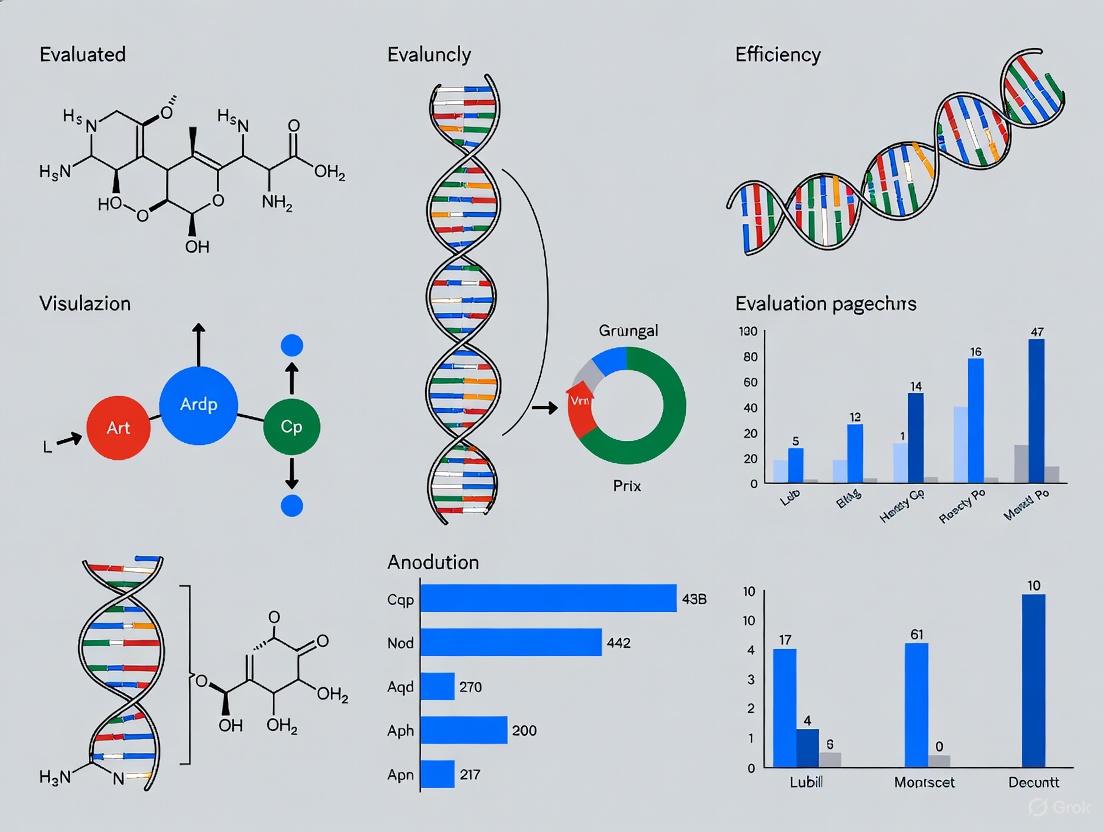

The diagram below illustrates the mechanistic divergence triggered by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), a key initiating molecule in both TGS and PTGS, depending on its sequence homology.

Figure 1: dsRNA-induced gene silencing pathways. TGS occurs with promoter homology, PTGS with coding sequence homology [1].

Key Experimental Protocol: Differentiating TGS and PTGS

A seminal experiment demonstrating the distinction between TGS and PTGS involved targeting flower pigmentation genes in Petunia [1].

1. Objective: To determine whether dsRNA induces TGS or PTGS based on the targeted sequence (promoter vs. coding region).

2. Methodology:

- Construct Design: Generate transgenes expressing dsRNA.

- Plant Transformation: Introduce the respective dsRNA-expressing constructs into Petunia plants.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Observe flower pigmentation patterns as a visual reporter of gene silencing.

- Molecular Analysis:

- mRNA Level Quantification: Use techniques like Northern blotting to measure the abundance of the target mRNA.

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Perform bisulfite sequencing on the gene's promoter region to detect cytosine methylation, a hallmark of TGS [1].

- Small RNA Detection: Isolate and sequence small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to confirm the involvement of the RNAi pathway [1].

3. Key Findings:

- dsRNA corresponding to a promoter sequence led to Transcriptional Gene Silencing (TGS), characterized by promoter methylation and a reduction in the synthesis of new mRNA [1].

- dsRNA corresponding to a coding sequence led to Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing (PTGS), characterized by normal transcription rates but rapid degradation of the existing mRNA [1].

- Both processes produced small RNA species and involved DNA methylation, suggesting a mechanistic relationship [1].

Performance and Efficiency Data

The following table synthesizes key performance metrics for common gene silencing technologies, highlighting their relative efficiencies and characteristics.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Gene Silencing Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism Type | Targeting Specificity | Efficiency | Reversibility | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNAi (siRNA/shRNA) | PTGS [2] | High (mRNA sequence) [2] | High (can achieve >70% knockdown) [2] | Reversible (transient) [2] | Functional genomics, therapeutic gene silencing [2] |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | PTGS [3] | High (mRNA sequence) [3] | Moderate to High [3] | Reversible (transient) | Treatment of genetic disorders (e.g., DMD, SMA) [3] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 (Knockout) | N/A (Gene editing) | High (DNA sequence) [2] | Very High (permanent disruption) [2] | Irreversible [2] | Gene knockout, functional genomics [2] |

| CRISPRi (dCas9) | TGS [2] | High (DNA promoter sequence) [2] | High (tunable repression) [2] | Reversible [2] | Reversible gene silencing, regulation of gene expression [2] |

| Promoter-targeted dsRNA | TGS [1] | High (DNA promoter sequence) [1] | Moderate to High (leads to promoter methylation) [1] | Can be stable/heritable [1] | Generating stable gene knockouts [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful gene silencing experiments require a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for planning and executing these studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Silencing Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| siRNAs / shRNAs | Small interfering RNAs or short hairpin RNAs that trigger the RNAi pathway for specific mRNA degradation [2]. | The cornerstone of PTGS experiments in functional genomics and therapeutic development [2]. |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | Single-stranded DNA/RNA molecules that bind to complementary mRNA, inducing its degradation or blocking translation [3]. | Used in PTGS for both research and approved therapeutics for neurological and genetic disorders [3]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | A complex of Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) that introduces double-strand breaks at specific genomic loci for gene knockout [2]. | Enables permanent gene disruption, distinct from but often compared with silencing technologies [2]. |

| CRISPRi (dCas9) Systems | A complex of catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) and gRNA that binds to DNA without cutting, blocking transcription (TGS) [2]. | Used for reversible, tunable transcriptional repression without altering the DNA sequence [2]. |

| Methylation-Specific PCR Reagents | Reagents and primers designed to detect methylated vs. unmethylated DNA, crucial for confirming TGS [1]. | Essential for validating the epigenetic marker (DNA methylation) associated with TGS in experimental analysis [1]. |

| Delivery Vectors (e.g., LNPs, Viral Vectors) | Lipid nanoparticles or engineered viruses (e.g., lentivirus, AAV) that package and deliver silencing constructs into cells [3]. | Critical for overcoming the primary challenge of intracellular delivery in both research and clinical settings [3]. |

Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing are distinct yet powerful strategies for controlling gene expression. The choice between TGS and PTGS depends on the research goal: TGS is suited for long-term, stable silencing through epigenetic modification, while PTGS is ideal for rapid, reversible knockdown of existing mRNA. Technologies like CRISPRi and promoter-targeted RNAi exploit TGS mechanisms, whereas RNAi and ASOs are pillars of PTGS. As the gene silencing market continues to grow, driven by advancements in delivery systems and the success of RNAi therapeutics, a deep understanding of these core mechanisms remains paramount for researchers and drug developers aiming to design efficient and specific genetic interventions.

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are synthetic, single-stranded nucleic acids, typically 15–30 nucleotides in length, designed to modulate gene expression by binding to target RNA sequences via Watson-Crick base pairing [4] [5] [6]. Their therapeutic application stems from their ability to precisely target and alter RNA function, offering a powerful strategy for treating genetic disorders [4] [5]. The clinical success of ASOs is evidenced by several FDA-approved drugs, such as Nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy and Tofersen for SOD1-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [5] [6]. The functional versatility of ASOs is largely categorized into two principal mechanistic classes: RNase H-dependent degradation and splice-switching modulation [5] [6]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two core mechanisms, focusing on their operational principles, experimental performance, and optimal research applications.

The fundamental distinction between these ASO classes lies in their site of action, molecular outcomes, and structural requirements.

RNase H-Dependent ASOs

These ASOs, often designed as gapmers, facilitate the enzymatic cleavage and degradation of their target RNA [4] [7] [6]. A gapmer is a chimeric oligonucleotide featuring a central DNA "gap" region flanked by chemically modified RNA-like nucleotides (e.g., 2'-MOE, 2'-OMe, or LNA) on both the 5' and 3' ends [7] [8]. The central DNA segment forms a heteroduplex with the complementary mRNA, which is recognized by the endogenous enzyme RNase H1 [7] [6]. This enzyme cleaves the RNA strand within the duplex, leading to the degradation of the target mRNA and a subsequent reduction in protein expression [4] [7]. This mechanism is primarily used for transcript knockdown to suppress the expression of genes harboring toxic gain-of-function mutations [4] [5].

Splice-Switching ASOs (SSOs)

Also known as steric-blocking ASOs, SSOs modulate pre-mRNA splicing by physically blocking access to key splice-regulatory elements without degrading the RNA [5] [6] [8]. They achieve this by binding to pre-mRNA sequences such as splice sites, branch points, or splicing enhancers/silencers, thereby preventing the spliceosome machinery from recognizing these elements [4] [5]. This action can lead to the exclusion (skipping) or inclusion of specific exons in the mature mRNA [4]. SSOs are typically fully modified along their entire length with chemistries like 2'-OMe, 2'-MOE, or phosphorodiamidate morpholino (PMO) that do not activate RNase H [7] [8]. Their primary application is to correct aberrant splicing caused by genetic mutations or to alter splicing patterns to restore protein function, making them ideal for addressing loss-of-function variants [4] [6].

The following diagram illustrates the key pathways and cellular locations for these two mechanisms.

Performance and Experimental Data

Direct comparisons of RNase H-dependent ASOs and SSOs reveal significant differences in their efficacy, optimal design, and functional outcomes.

Table 1: Head-to-Head Comparison of Key Characteristics

| Parameter | RNase H-Dependent ASOs | Splice-Switching ASOs (SSOs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Catalytic degradation of target mRNA via RNase H1 [7] [6] | Steric blockade of splicing factors to alter pre-mRNA processing [4] [8] |

| Primary Application | Knockdown of gene expression (e.g., for gain-of-function mutations) [4] [5] | Correction of aberrant splicing; modulation of protein isoforms [4] [6] |

| Typical Chemistry | Gapmer design (e.g., 5-10-5 2'MOE/DNA/2'MOE) [7] | Fully modified backbone (e.g., 2'OMe, PMO, 2'MOE) [7] [8] |

| Cellular Localization | Nucleus and Cytosol [7] | Nucleus [9] |

| Therapeutic Example | Tofersen (SOD1-ALS) [5] | Nusinersen (SMA), Eteplirsen (DMD) [5] [6] |

| Key Consideration | Requires a contiguous DNA "gap" (≥8 nt) for RNase H recruitment [6] | Must use non-RNase H activating chemistry to avoid mRNA degradation [7] |

Quantitative data further highlights performance differences under experimental conditions. A study targeting the CTNNB1 gene demonstrated the relative potency of different gapmer chemistries used in RNase H-dependent silencing, which can be benchmarked against the efficacy typically observed with SSOs in splicing correction assays.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of ASO Performance in Model Systems

| ASO Type / Experiment | Chemical Modification | Observed Efficacy | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase H-Dependent (Gapmer) [7] | Affinity Plus (LNA) / DNA (3-10-3) | ~80% Gene Knockdown | CTNNB1 mRNA reduction in cell culture |

| RNase H-Dependent (Gapmer) [7] | 2'-MOE / DNA (5-10-5) | ~70% Gene Knockdown | CTNNB1 mRNA reduction in cell culture |

| RNase H-Dependent (Gapmer) [7] | 2'-OMe / DNA (5-10-5) | ~60% Gene Knockdown | CTNNB1 mRNA reduction in cell culture |

| Splice-Switching ASO [9] | 2'-OMe (Fully PS-modified) | ~2.0-fold increase in splice correction | HeLa pLuc/705 luciferase splice-correction assay (25 nM) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reliable and reproducible results, researchers must adhere to protocol specifics for each ASO type.

Protocol for Evaluating RNase H-Dependent ASOs (Gapmers)

This protocol is designed for in vitro assessment of gapmer efficacy in cell cultures [10] [7].

ASO Design and Synthesis:

- Design a gapmer structure with a central DNA block of at least 8-10 nucleotides flanked by 3-5 high-affinity modified nucleotides (e.g., 2'-MOE, LNA) on each side [7] [8].

- Incorporate phosphorothioate (PS) linkages throughout the backbone to enhance nuclease resistance and cellular uptake [7] [8].

- Control: Include a mismatch control (MM) ASO with a scrambled sequence or several base-pair mismatches [10].

Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Culture appropriate cell lines (e.g., U87-MG glioblastoma cells) under standard conditions [10].

- Plate cells at 30-50% confluence the day before transfection to ensure exponential growth during the experiment [10].

- Transfect ASOs using a suitable transfection reagent such as Oligofectamine or Lipofectin. A common working concentration is 50-100 nM, but a dose-response curve (e.g., 25-200 nM) is recommended for optimization [10].

- For sustained knockdown, a second transfection 24 hours after the first may be performed [10].

Harvesting and Analysis:

- Time Point: Harvest cells 48 hours after the final transfection. Microarray studies suggest that PDK1-specific patterns are most detectable at this time point, before being obscured by non-specific transcriptional changes at 72 hours [10].

- Efficacy Assessment:

Protocol for Evaluating Splice-Switching ASOs (SSOs)

This protocol uses a luciferase-based reporter system to quantitatively measure splice correction [9].

ASO Design and Synthesis:

- Design SSOs to be fully complementary to the target splice-regulatory element (e.g., a cryptic splice site) [4].

- Use steric-blocking chemistries such as 2'-OMe, 2'-MOE, or PMO with a full phosphorothioate or morpholino backbone. Crucially, avoid DNA residues that activate RNase H [7] [8].

- Control: Include a scrambled sequence control oligonucleotide with the same chemistry.

Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Utilize the HeLa pLuc/705 reporter cell line. This cell line stably expresses a luciferase gene whose coding sequence is interrupted by a mutated β-globin intron that causes aberrant splicing and loss of luciferase activity [9].

- Plate HeLa pLuc/705 cells and transfert with SSOs using standard methods. Test a concentration range (e.g., 25-200 nM for lipofected delivery; 5-20 μM for gymnotic/non-transfected delivery) [9].

Harvest and Readout:

- Time Point: Incubate for 24 hours post-transfection [9].

- Efficacy Assessment:

- Lyse cells and measure luciferase activity using a luminometer. Successful splice correction restores the luciferase reading frame, resulting in increased luminescence, which serves as a direct and quantitative measure of SSO efficacy [9].

- Normalize luminescence readings to total protein concentration (e.g., via BCA assay) to account for variations in cell number or viability [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful ASO experimentation requires a selection of specialized reagents and tools. The following table lists key solutions for researchers.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASO Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gapmer ASOs (2'MOE, LNA) | To achieve catalytic degradation of target mRNA via RNase H [7] | Knockdown of genes with toxic gain-of-function mutations [4] |

| Splice-Switching ASOs (2'OMe, PMO) | To sterically block the spliceosome and alter exon inclusion/exclusion [7] [8] | Correction of splicing defects in diseases like DMD or SMA [6] |

| Phosphorothioate (PS) Linkages | Increases nuclease resistance and promotes binding to serum proteins, improving bioavailability and cellular uptake [7] [8] | Standard modification for both gapmer and SSO designs for in-cellulo and in vivo activity [7] |

| HeLa pLuc/705 Cell Line | A reporter cell line for quantitatively measuring splice-switching activity via luciferase readout [9] | High-throughput screening and validation of SSO efficacy [9] |

| Lipofectamine / Oligofectamine | Cationic lipid-based transfection reagents for delivering oligonucleotides into cells [10] | Routine transient transfection of ASOs into various mammalian cell lines [10] |

| Mismatch Control (MM) ASO | A control oligonucleotide with a scrambled or mismatched sequence to account for sequence-independent effects [10] | Critical for validating that the observed phenotypic effects are due to on-target ASO activity [10] |

RNase H-dependent ASOs and splice-switching ASOs are distinct tools, each with a defined mechanistic basis and application scope. The choice between them is not one of superiority but of strategic alignment with the research goal. RNase H-dependent gapmers are the definitive choice for robust mRNA knockdown, while SSOs offer a unique capability to reprogram genetic information at the pre-mRNA level. A clear understanding of their comparative profiles—summarized in the performance data, protocols, and reagent tables provided—enables researchers to make informed decisions, thereby optimizing experimental design and accelerating the development of effective oligonucleotide-based therapies.

RNA interference (RNAi) is a highly conserved biological mechanism for gene regulation that operates at the post-transcriptional level by silencing messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules [11]. Central to the RNAi pathway is the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), a multiprotein complex that functions as the primary effector machinery for gene silencing [12]. RISC is a ribonucleoprotein complex that utilizes small RNA strands as guides to identify complementary mRNA transcripts for silencing through various mechanisms [13]. The core component of RISC is the Argonaute (Ago) protein family, which binds the small RNA guide strand and positions it to facilitate target recognition; some Argonaute proteins can directly cleave target RNAs, while others recruit additional gene-silencing proteins [13]. The composition and size of RISC can vary significantly, ranging from a minimal complex of approximately 160 kDa, consisting essentially of Argonaute bound to a small RNA, to larger "holo-RISC" complexes of up to 3 MDa that include numerous associated proteins [13] [12].

Two major classes of small RNAs that program RISC are small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), both of which are central to this comparative analysis. Since its discovery following the initial description of RNAi by Andrew Fire and Craig Mello in 1998 (who received the 2006 Nobel Prize for this work), and the subsequent biochemical identification of RISC by Gregory Hannon and colleagues, the field has rapidly advanced [12]. The RNAi machinery has been co-opted as an powerful experimental tool for basic research and holds transformative potential for therapeutic development to treat devastating diseases [14] [15]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of siRNA and miRNA pathways, with a focus on RISC complex formation and function, to aid researchers in evaluating the efficiency of these gene-silencing oligonucleotides.

Comparative Pathways: siRNA and miRNA

Although siRNAs and miRNAs both utilize the RISC to regulate gene expression, their origins, mechanisms of biogenesis, and modes of action differ significantly. The diagrams below illustrate the distinct pathways for siRNA and miRNA.

siRNA Pathway

Figure 1: The siRNA Pathway. This pathway begins with the introduction of long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) from exogenous sources, such as viruses or experimentally introduced synthetic RNA. The core steps are:

- Dicer Processing: The RNase III enzyme Dicer cleaves long dsRNA into short siRNA duplexes of 21-23 base pairs with 2-nucleotide 3' overhangs [12] [16].

- RISC Loading: The siRNA duplex is loaded into the RISC Loading Complex (RLC). In Drosophila, a heterodimer of Dicer-2 and the protein R2D2 facilitates this process, with R2D2 binding the thermodynamically more stable end of the duplex [17].

- Strand Selection and Unwinding: The siRNA duplex is unwound, and the passenger strand is selectively degraded. The strand with the less thermodynamically stable 5' end is preferentially retained as the guide strand [12].

- Target Cleavage: The mature RISC, containing the guide strand and Argonaute 2 (Ago2), binds perfectly complementary mRNA sequences. The Ago2 protein, which has slicer activity, cleaves the target mRNA, leading to its degradation [17] [12].

miRNA Pathway

Figure 2: The miRNA Pathway. This pathway involves endogenous genes and regulates physiological gene expression. The core steps are:

- Transcription and Nuclear Processing: miRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II to produce primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs). The enzyme Drosha processes pri-miRNAs in the nucleus to form precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs), which have a stem-loop structure of about 70-90 nucleotides [17] [11].

- Nuclear Export and Dicing: Pre-miRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm by Exportin-5. Subsequently, Dicer cleaves the pre-miRNA loop, generating a short miRNA duplex [17] [11].

- RISC Loading and Maturation: Similar to siRNAs, the miRNA duplex is loaded into RISC, the passenger strand is discarded, and the guide strand is retained.

- Translational Repression: The mature miRNA-RISC complex typically binds to the 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) of target mRNAs with partial complementarity, leading to translational repression or mRNA destabilization without cleavage [11] [12]. A single miRNA can regulate hundreds of different mRNA targets [11].

Key Functional Differences and Efficiencies

The distinct biogenesis and mechanisms of action of siRNAs and miRNAs lead to significant differences in their biological roles, silencing efficiency, and specificity, which are critical for research and therapeutic applications.

Table 1: Functional Comparison of siRNA and miRNA

| Feature | siRNA | miRNA |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Exogenous (viruses, synthetic) [11] | Endogenous (encoded in genome) [11] |

| Precursor Structure | Long, double-stranded RNA [12] | Short, single-stranded RNA with stem-loop (pri-miRNA, pre-miRNA) [17] [11] |

| Complementarity | Perfect or near-perfect match to target [12] | Partial match, especially in "seed region" (nucleotides 2-8) [13] [11] |

| Primary Mechanism | mRNA cleavage and degradation [11] [12] | Translational repression and mRNA destabilization [11] [12] |

| Specificity | High specificity for a single target mRNA [11] | Broad specificity; regulates multiple mRNAs and pathways [11] |

| Amplification | RISC is catalytic and can cleave multiple mRNAs [15] | RISC is catalytic and can repress multiple mRNAs [15] |

| Primary Application | Research: Knockdown of specific genes. Therapeutics: Silence disease-causing genes [14] [11] | Research: Study gene regulatory networks. Therapeutics: miRNA mimics/inhibitors to modulate pathways [11] |

RISC Assembly and Strand Selection

A critical determinant of efficiency for both siRNAs and miRNAs is the proper loading into RISC and the selection of the active guide strand. This process is governed by the "asymmetry rule": the strand whose 5' end is less thermodynamically stable is preferentially loaded into RISC as the guide strand, while the other strand (the passenger strand) is degraded [17] [12]. The 5'-phosphate of the guide strand is anchored in a binding pocket between the MID and PIWI domains of the Argonaute protein, while the 3'-end is clamped by the PAZ domain [13]. The inherent asymmetry in the thermodynamic stability of the duplex ends is thought to be sensed by proteins in the RISC Loading Complex (e.g., the R2D2 protein in Drosophila), which helps direct the strand selection process [17].

Experimental Considerations for siRNA and miRNA Research

Design and Efficiency Parameters for siRNA

For experimental research using synthetic siRNAs, careful design is paramount for achieving high silencing efficiency and minimizing off-target effects. Key parameters are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Design Parameters for Efficient Synthetic siRNA

| Parameter | Optimal Characteristic | Rationale & Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 30-52% [17] [18] | Prevents overly stable duplexes that resist RISC unwinding; GC content >60% negatively impacts silencing [14] [18]. |

| Thermodynamic Asymmetry | Unstable 5' end of the guide strand (A/U rich) [17] [18] | Ensures correct guide strand incorporation into RISC; a lower relative thermodynamic stability at the 5' antisense end improves RISC loading efficiency [17]. |

| Seed Region (pos 2-8) | Avoid G-quadruplexes and high stability [18] | Critical for initial target recognition; strong base-pairing in off-target transcripts can cause miRNA-like off-target effects [18]. |

| Nucleotide Preferences | A/U at positions 15-19; A at position 19; A at position 3; U at position 10 [17] | Empirical rules derived from large-scale screens of functional siRNAs; enhance silencing potency [17]. |

| Target mRNA Region | 50-100 nt downstream of start codon; CDS over UTRs [18] | Regions with less stable secondary structure and reduced interference from ribosomal machinery improve efficiency [14] [18]. |

| Off-Target Filtering | BLAST against transcriptome/genome [14] [18] | Removes siRNAs with significant homology to other genes, reducing unintended silencing of off-target transcripts [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for siRNA and miRNA Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Example Product Lines |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-designed Synthetic siRNAs | Synthetic duplexes designed for high-specificity knockdown of a single target gene. Ideal for loss-of-function studies. | Silencer Select (Thermo Fisher) [11] |

| miRNA Mimics | Synthetic small RNAs that mimic endogenous mature miRNAs. Used for gain-of-function studies to observe downstream protein down-regulation. | mirVana Mimics (Thermo Fisher) [11] |

| miRNA Inhibitors | Single-stranded antisense oligonucleotides that bind to and inhibit endogenous miRNAs. Used for loss-of-function studies resulting in protein up-regulation. | mirVana Inhibitors (Thermo Fisher) [11] |

| Chemically Modified Nucleotides | Enhance stability, half-life, and safety of RNA oligonucleotides (e.g., 2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro, phosphorothioate) [14] [15]. | Component of therapeutic and advanced research siRNAs/miRNAs |

| Bioinformatics Design Tools | Algorithms and software for selecting highly active and specific siRNA sequences based on rules and machine learning. | BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer (Thermo Fisher), siRNA Wizard (InvivoGen) [15] [18] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Facilitate cellular uptake of oligonucleotides (e.g., Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), GalNAc conjugates for hepatocyte targeting) [15] [18]. | Various commercial transfection reagents and formulation systems |

Advanced Design and Modification Strategies

Current research and therapeutic development heavily rely on chemical modifications to improve the properties of synthetic siRNAs. A 2025 systematic study analyzing ~1260 modified siRNAs revealed that the modification pattern (e.g., the level of 2'-O-methyl content) significantly impacts efficacy, while structural features like symmetric versus asymmetric configurations do not [14]. Common modifications include:

- Ribose modifications (2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro) to increase nuclease resistance and binding affinity [15] [19].

- Phosphonate modifications (Phosphorothioate, PS) in the backbone to confer resistance to nucleases and improve pharmacokinetics [15] [18]. These modifications are essential for stabilizing siRNAs in the harsh endosomal environment and are a key factor in the long-term efficacy of siRNA drugs by creating an intracellular depot that is slowly released into the cytoplasm [14].

Furthermore, modern siRNA design has moved beyond simple rule-based algorithms. Machine learning and deep learning models (e.g., neural networks, graph neural networks) are now trained on large datasets of experimentally validated siRNAs to discern complex patterns and provide significantly enhanced predictive accuracy for silencing efficiency [15] [19]. These models can also integrate predictions for the efficacy of chemically modified siRNAs, addressing a critical gap in the design pipeline [19].

The siRNA and miRNA pathways, while sharing the common effector complex RISC, offer distinct tools for gene regulation research and therapeutic development. siRNAs are the tool of choice for achieving potent and specific knockdown of a single gene, making them ideal for functional genetics and targeted therapies. In contrast, miRNAs are invaluable for studying broader gene regulatory networks and complex biological processes. The efficiency of both exogenous siRNA and endogenous miRNA is fundamentally governed by the precise molecular mechanisms of RISC assembly, strand selection, and target recognition. Continued advancements in the understanding of RISC biology, coupled with sophisticated design algorithms and strategic chemical modifications, are key to harnessing the full potential of these powerful gene-silencing technologies.

The evolution from early oligonucleotide drugs (ODNs) to modern RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutics represents one of the most significant advancements in molecular medicine. This transition has enabled researchers to target previously "undruggable" pathways with unprecedented specificity, fundamentally expanding the therapeutic landscape for genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases [20]. The initial discovery of RNAi as a natural cellular process in 1998, followed by its systematic characterization, earned Andrew Fire and Craig Mello the Nobel Prize in 2006 and catalyzed the development of an entirely new class of therapeutics [21] [22]. Unlike traditional small molecule drugs that target proteins, RNAi therapeutics operate at the post-transcriptional level, selectively degrading messenger RNA (mRNA) before translation occurs, thereby preventing the synthesis of disease-causing proteins [23].

This revolutionary approach offers distinct advantages over conventional therapeutic modalities, including the ability to target virtually any gene with high specificity, cost-effective design processes compared to recombinant proteins, rapid production capabilities, and no risk of genotoxic effects associated with DNA therapeutics [20]. The commercial approval of Onpattro (patisiran) in 2018 marked a watershed moment as the first RNAi-based therapeutic approved for clinical use, validating decades of research and opening the floodgates for further development [21]. Subsequent approvals, including givosiran for acute hepatic porphyria, lumasiran for primary hyperoxaluria type 1, and inclisiran for hypercholesterolemia, have further established RNAi as a transformative therapeutic platform [21]. According to current industry analysis, there are over 260 siRNA drug candidates in preclinical or clinical development, targeting conditions from cancer to Alzheimer's disease to HIV [21].

Historical Timeline: Key Milestones in Oligonucleotide Therapeutics

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Oligonucleotide Therapeutics

| Time Period | Therapeutic Class | Key Milestones | Representative Approved Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990-2000 | Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | First-generation modifications; FDA approval of Fomivirsen (1998) for CMV retinitis | Fomivirsen, Mipomersen, Defibrotide |

| 2001-2010 | Refined ASOs & Early RNAi | RNAi mechanism discovery (Nobel Prize 2006); Improved ASO chemistries | Nusinersen, Inotersen |

| 2011-Present | Modern RNAi Therapeutics | First siRNA approval (2018); GalNAc conjugation technology; LNPs for delivery | Patisiran, Givosiran, Lumasiran, Inclisiran |

The historical development of oligonucleotide therapeutics began with antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) in the 1990s, which are chemically synthesized single-stranded oligonucleotides typically 12-25 nucleotides in length designed to bind target RNA through Watson-Crick hybridization [20]. These early ODNs functioned primarily through occupancy-only mechanisms or RNA degradation via RNase H activation, with pioneering drugs like Fomivirsen demonstrating clinical validation of the oligonucleotide approach despite limitations in stability and delivery efficiency [20].

The paradigm shift began with the discovery of RNA interference (RNAi), a natural cellular process that regulates gene expression through sequence-specific gene silencing at the translational level by degrading specific messenger RNAs [23]. This breakthrough understanding revealed that double-stranded RNA molecules could trigger a highly precise cellular machinery that evolved as an antiviral defense mechanism [24]. The subsequent identification that small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) of 21-23 base pairs could mediate RNAi in mammalian cells without triggering the interferon response opened the door for therapeutic applications [22].

The period from 2010 onward witnessed accelerated development of delivery technologies, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and GalNAc conjugates, which effectively addressed the primary challenges of stability, tissue-specific targeting, and intracellular delivery that had hampered earlier oligonucleotide therapeutics [20] [21]. The success of these platforms culminated in the current era of RNAi therapeutics, with multiple FDA-approved products and an expanding pipeline targeting various disease areas [22].

Comparative Mechanisms: ASOs versus RNAi Therapeutics

Table 2: Mechanism Comparison Between ASOs and RNAi Therapeutics

| Characteristic | Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | RNAi Therapeutics (siRNAs) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Single-stranded, 12-25 nucleotides | Double-stranded, 21-23 bp with 2-nt 3' overhangs |

| Mechanism of Action | RNase H activation, splicing modulation, translational arrest | RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage and degradation |

| Specificity | High, but potential for off-target effects | Very high, with precise sequence complementarity requirements |

| Catalytic Activity | Non-catalytic (occupancy) or catalytic (RNase H) | Catalytic (RISC recycled for multiple rounds) |

| Therapeutic Scope | Protein reduction, splicing modification, translational repression | Primarily gene silencing through mRNA degradation |

The fundamental distinction between early ODNs and modern RNAi therapeutics lies in their mechanisms of action. ASOs are typically single-stranded and can function through multiple mechanisms, including RNase H-mediated degradation of the target RNA, modulation of RNA splicing through exon skipping or inclusion, or translational arrest by binding to regulatory sequences [20]. This versatility enables diverse therapeutic applications, as evidenced by approved ASOs that reduce pathogenic protein levels, enhance functional proteins, or modify defective protein structures [20].

In contrast, RNAi therapeutics, particularly siRNAs, operate through a highly conserved pathway initiated by the enzyme Dicer, which processes double-stranded RNA into 21-23 nucleotide siRNA duplexes [23]. These siRNAs are then incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where the guide strand directs sequence-specific recognition and cleavage of complementary mRNA targets through the catalytic activity of Argonaute 2 (AGO2) [23] [21]. The cleaved mRNA fragments are subsequently degraded by cellular nucleases, effectively preventing translation of the target protein [21].

A key advantage of the RNAi pathway is its catalytic nature—once activated, a single RISC complex can facilitate the cleavage of multiple mRNA molecules, providing amplified silencing effects from limited therapeutic doses [23]. Additionally, the requirement for near-perfect complementarity between the siRNA guide strand and its target mRNA, particularly within the "seed region" (nucleotides 2-8), enhances specificity and reduces off-target effects compared to earlier ASO approaches [23].

(Diagram 1: Comparative Mechanisms of ASOs and siRNA Therapeutics)

Technological Advancements: Delivery Systems and Chemical Modifications

The transition from early ODNs to modern RNAi therapeutics required solving fundamental delivery challenges. Unmodified siRNAs face rapid degradation by serum nucleases, poor cellular internalization due to their hydrophilic nature and negative charge, renal clearance, and potential immunogenicity [20] [21]. Two key technological breakthroughs have addressed these limitations: advanced chemical modifications and sophisticated delivery systems.

Chemical Modifications

Comprehensive chemical modification strategies have been developed to enhance siRNA stability, specificity, and pharmacokinetic properties while reducing immunogenicity [21]. These include:

- Sugar modifications: 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), and 2'-fluoro (2'-F) substitutions improve nuclease resistance and reduce immune stimulation [21] [25]. Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) modifications with their constrained bicyclic structure confer high binding affinity [21].

- Backbone modifications: Phosphorothioate (PS) linkages, where a non-bridging oxygen is replaced with sulfur, significantly increase resistance to nuclease degradation and enhance plasma protein binding, thereby extending circulation half-life [21] [25].

- Terminal and conjugate modifications: 5'-(E)-vinylphosphonate (5'-VP) modifications increase siRNA accumulation in tissues by 2- to 22-fold and enhance mRNA silencing potency, particularly in rapidly dividing cells [26]. Conjugation with targeting ligands like GalNAc enables hepatocyte-specific delivery through the asialoglycoprotein receptor [21].

Recent research demonstrates that optimized chemical structures, particularly fully modified backbones combined with 5'-VP stabilization, can extend silencing duration from days to several weeks even in rapidly dividing cancer and immune cells—a previously significant challenge [26].

Delivery Systems

Advanced delivery platforms have been crucial for translating RNAi therapeutics to clinical applications:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): The most clinically advanced platform, LNPs combine ionizable lipids, helper lipids, PEGylated lipids, and cholesterol to encapsulate and protect siRNAs, facilitating cellular uptake and endosomal escape [20] [21]. Patisiran (Onpattro) utilizes this technology for treating hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis [21].

- Ligand Conjugates: GalNAc-siRNA conjugates represent a breakthrough in targeted delivery, enabling efficient hepatocyte uptake through receptor-mediated endocytosis with potency allowing subcutaneous administration every 3-6 months [21] [22].

- Polymeric Nanoparticles: Cationic polymers like polyethyleneimine (PEI), poly-L-lysine (PLL), chitosan, and PLGA form polyplexes with siRNAs through electrostatic interactions, protecting them from degradation and enhancing cellular uptake [20] [25].

- Advanced Platforms: Emerging technologies include cholesterol-enriched exosomes that enable direct cytosolic delivery via membrane fusion, bypassing endosomal entrapment [27], and self-assembled RNA nanostructures (SARNs) that enhance stability and delivery efficiency [28].

Table 3: Evolution of Delivery Systems for Oligonucleotide Therapeutics

| Delivery System | Generation | Key Features | Clinical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naked Oligonucleotides | First | Minimal modification, rapid degradation, limited bioavailability | Early ASOs (Fomivirsen) |

| Lipid-Based Systems | Second | Enhanced stability, improved cellular uptake, endosomal escape | Patisiran (LNP) |

| Ligand-Conjugated | Third | Tissue-specific targeting, reduced dosing frequency | Givosiran, Inclisiran (GalNAc) |

| Engineered Nanoplatforms | Emerging | Biomimetic designs, multifunctionality, enhanced penetration | Cholesterol-enriched exosomes, SARNs |

Clinical Applications and Efficacy Data

The therapeutic efficacy of RNAi therapeutics has been demonstrated across multiple disease areas, with particularly notable success in genetic disorders and hepatic diseases.

Approved Therapeutics and Clinical Performance

- Patisiran (Onpattro): For hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, demonstrated significant improvement in neuropathy impairment scores compared to placebo in clinical trials, with dosing every 3 weeks [20] [22].

- Givosiran (Givlaari): For acute hepatic porphyria, reduced annualized attack rates by 74% compared to placebo in phase 3 trials, with monthly subcutaneous administration [27] [26].

- Inclisiran (Leqvio): For hypercholesterolemia, provides sustained reduction of LDL cholesterol with dosing just twice per year, dramatically improving patient compliance [21] [22].

The duration of silencing effect varies significantly between non-dividing and rapidly dividing cells. In non-dividing hepatocytes, chemically modified siRNAs can maintain silencing for up to 6-18 months, with one clinical study reporting effects lasting up to 680 days after a single administration [26]. In contrast, early siRNA designs in rapidly dividing cells typically showed silencing durations of only 3-7 days in vitro, though advanced chemical modifications including 5'-VP stabilization have extended this to 3-4 weeks in preclinical cancer models [26].

Comparative Efficacy in Different Tissue Types

The efficiency of RNAi therapeutics varies considerably across tissues and cell types, influenced by delivery efficiency, cellular turnover rates, and intracellular processing. Hepatocytes have proven particularly amenable to RNAi targeting, benefiting from natural accumulation mechanisms and relatively slow division rates [26]. Other tissues present greater challenges:

- Cancer Cells: Rapid division historically limited silencing duration due to dilution effects, but optimized chemistries now enable sustained silencing through multiple cell divisions [26].

- Immune Cells: Difficult to transferect but crucial for immunotherapeutic applications; novel delivery platforms like cholesterol-enriched exosomes show improved uptake and silencing in T cells [27].

- Neurological Tissue: The blood-brain barrier presents significant delivery challenges, though intrathecal administration and novel nanoparticle systems show promise [20].

Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Evaluation

In Vitro Silencing Efficacy Assessment

Protocol: Quantitative Evaluation of Gene Silencing in Cell Culture

- siRNA Preparation: Synthesize siRNA with appropriate chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-F, 2'-OMe, phosphorothioate, 5'-VP) using solid-phase phosphoramidite chemistry [26].

- Delivery Formulation: Complex siRNAs with delivery vehicles (e.g., LNPs at nitrogen-to-phosphate ratio 5:1, polymer-based nanoparticles, or commercial transfection reagents like RNAiMAX) in serum-free medium [27] [26].

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Plate appropriate cell lines (e.g., HCT116 colorectal cancer cells for oncology models, primary hepatocytes for metabolic diseases) at 30-50% confluence in 24-well plates. Transfert with siRNA concentrations typically ranging from 1-100 nM [26].

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate for 24-72 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Collect cells at multiple time points (24h, 48h, 72h, 7d, 14d) to assess silencing kinetics and duration [26].

- Efficacy Analysis:

- Extract total RNA and perform quantitative RT-PCR to measure target mRNA levels normalized to housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) [26].

- Analyze protein reduction via Western blotting or ELISA for targets where antibodies are available.

- Calculate percentage silencing compared to non-targeting siRNA controls.

- Cell Proliferation Monitoring: For dividing cells, track cell counts and division rates throughout the experiment to account for siRNA dilution effects [26].

In Vivo Therapeutic Efficacy Assessment

Protocol: Preclinical Evaluation in Disease Models

- Animal Models: Select appropriate disease models (e.g., transgenic mice for genetic disorders, xenograft models for cancer, diet-induced models for metabolic diseases) [27] [26].

- Formulation and Dosing:

- For hepatocyte targets: Prepare GalNAc-conjugated siRNAs in phosphate-buffered saline for subcutaneous injection [21].

- For systemic delivery: Formulate siRNAs in LNPs (ionizable lipid:DSPC:cholesterol:PEG-lipid at 50:10:38.5:1.5 molar ratio) for intravenous administration [20].

- For oral delivery: Utilize engineered exosomes (e.g., cholesterol-enriched exosomes) protected from gastrointestinal degradation [27].

- Administration and Monitoring: Administer siRNA therapeutics at doses typically ranging from 1-10 mg/kg. Monitor animals for signs of toxicity and disease progression [26].

- Efficacy Endpoints:

- Collect tissue samples at predetermined endpoints (e.g., tumors, liver, plasma) for mRNA and protein analysis [26].

- For cancer models: Measure tumor volume regularly using calipers or imaging (e.g., bioluminescence) [27].

- For genetic/metabolic disorders: Assess relevant biomarkers in plasma or tissue homogenates.

- Duration Studies: For assessing silencing longevity, administer single doses and monitor effects over extended periods (weeks to months), with serial sampling where possible [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Oligonucleotide Therapeutics Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Synthesis | Phosphoramidite reagents (2'-F, 2'-OMe, 2'-MOE, LNA); Solid supports (CPG) | siRNA synthesis with custom modifications | Enables incorporation of stability-enhancing modifications |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid nanoparticles (IONizable lipids, DSPC, cholesterol, PEG-lipids); Polyethylenimine (PEI); Chitosan | Cellular delivery formulation | Protects siRNA, enhances cellular uptake, facilitates endosomal escape |

| Transfection Reagents | RNAiMAX; Lipofectamine 2000 | In vitro screening | Enables efficient siRNA delivery in cell culture models |

| Analytical Tools | qRT-PCR systems; Western blot reagents; ELISA kits; Nuclease stability assays | Efficacy assessment | Quantifies target gene silencing at mRNA and protein levels |

| Animal Models | Xenograft models; Transgenic mice; Disease-specific models | In vivo efficacy testing | Provides physiologically relevant context for therapeutic evaluation |

The historical evolution from early ODNs to modern RNAi therapeutics represents a remarkable journey from fundamental biological discovery to clinical transformation. The key differentiators—including catalytic mechanism of action, high specificity, and durable effects—position RNAi therapeutics as a cornerstone of precision medicine. Current research focuses on expanding the therapeutic landscape beyond hepatic disorders to include cancer, neurological diseases, and inflammatory conditions through continued innovation in delivery technologies and chemical modifications [20] [22].

The emerging breakthroughs in oral siRNA delivery [27], tissue-specific targeting platforms, and combination approaches with other modalities like CRISPR suggest that the full potential of RNAi therapeutics is yet to be realized. As the field continues to evolve, the ongoing refinement of efficiency, specificity, and delivery will undoubtedly unlock new therapeutic possibilities, ultimately fulfilling the promise of targeting previously undruggable pathways across the spectrum of human disease.

Gene silencing oligonucleotides represent a powerful therapeutic strategy for targeting previously "undruggable" genes in diseases like cancer [29]. Their efficacy is not inherent but depends on efficient engagement with the cell's intrinsic RNA silencing machinery. Three key enzymatic players—Dicer, Argonaute 2 (Ago2), and RNase H—orchestrate distinct silencing pathways, each with unique mechanisms that critically influence the design and performance of therapeutic oligonucleotides [30] [29]. This guide objectively compares these pathways, providing structured experimental data and methodologies to inform research and drug development.

Core Silencing Machinery: A Comparative Analysis

The efficiency of gene silencing is fundamentally determined by the cellular enzyme a therapeutic oligonucleotide is designed to engage. The table below provides a detailed comparison of the three core enzymes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Gene Silencing Enzymes

| Feature | Dicer | Argonaute 2 (Ago2) | RNase H |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Initiator of RNAi; processes long dsRNA and pre-miRNAs into siRNAs/miRNAs [12] [29] | Catalytic core of RISC; executes mRNA slicing and guides translational repression [30] [12] | DNA-RNA hybrid cleaving enzyme; not part of the RNAi pathway [31] |

| Mechanism of Action | RNase III enzyme; cleaves dsRNA to produce ~22 nt duplexes with 2-nt 3' overhangs [29] | "Slicer" activity; cleaves target mRNA complementary to the loaded guide strand [30] [12] | Endonuclease; cleaves the RNA strand in a DNA-RNA duplex [31] |

| Key Substrates | Long dsRNA, pre-miRNAs [29] | siRNA-loaded RISC, miRNA-loaded RISC, Dicer-independent shRNAs [30] | DNA-RNA heteroduplexes [31] |

| Therapeutic Oligo Engagement | Processes conventional shRNAs into functional siRNAs [30] | Directly processes and utilizes AgoshRNAs; cleaves mRNA targeted by siRNAs [30] | Activated by antisense DNA oligonucleotides (ASOs) to cleave complementary mRNA [31] |

| Silencing Outcome | Gene silencing via siRNA production for RISC loading [29] | Direct mRNA cleavage (perfect complementarity) or translational repression (miRNA-like) [30] [12] | mRNA degradation [31] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Silencing Efficiency

Robust experimental validation is essential for evaluating oligonucleotide performance. The following protocols are standard in the field for quantifying silencing efficacy and mechanism.

Testing Dicer-Dependent shRNA Processing

This protocol verifies that a designed short hairpin RNA (shRNA) is correctly processed by Dicer into an active siRNA.

- Step 1: In Vitro Dicer Cleavage Assay. Incubate the synthesized shRNA (e.g., 29 bp stem) with recombinant human Dicer enzyme in a suitable reaction buffer. Use a typical ratio of 1 µg shRNA to 1 unit of Dicer for 24 hours at 37°C [30].

- Step 2: Product Analysis. Analyze the reaction products by high-resolution denaturing urea-PAGE (15-20%). A successfully processed shRNA will show a distinct band at approximately 21-23 nucleotides, corresponding to the liberated siRNA duplex [30] [32].

- Step 3: Validation. Compare the migration of the product against a synthetic siRNA duplex of the same sequence to confirm correct processing.

Validating Ago2's Catalytic "Slicer" Activity

This experiment demonstrates Ago2's ability to directly cleave a target mRNA.

- Step 1: RISC Assembly. Form the active RISC complex by incubating a synthetic siRNA (perfectly complementary to your target mRNA) with purified Ago2 protein in RISC assembly buffer (e.g., containing ATP and Mg²⁺) [33].

- Step 2: Cleavage Reaction. Add a radiolabeled or fluorescently tagged mRNA transcript containing the target site to the assembled RISC. Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours [30].

- Step 3: Detection. Resolve the products by denaturing PAGE. Successful Ago2 cleavage produces two smaller, distinct RNA fragments compared to the full-length mRNA control [30].

Confirming RNase H-Mediated mRNA Cleavage

This protocol confirms the activation of RNase H by a DNA-based antisense oligonucleotide (ASO).

- Step 1: Duplex Formation. Anneal a complementary DNA ASO to a radiolabeled target mRNA transcript to form a DNA-RNA heteroduplex [31].

- Step 2: Enzyme Incubation. Incubate the heteroduplex with purified RNase H in an appropriate buffer (e.g., containing MgCl₂) at 37°C for 30-60 minutes [31].

- Step 3: Analysis. Visualize the cleavage products via denaturing urea-PAGE. RNase H activity will result in specific cleavage fragments of the mRNA, while the DNA ASO remains intact and can be re-used [31].

Visualization of Gene Silencing Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the canonical and non-canonical pathways, highlighting the distinct roles of Dicer and Ago2.

Canonical vs. Non-Canonical RNAi Pathways

RISC Assembly and Silencing Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful investigation into gene silencing pathways relies on specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details essential tools for related research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Silencing Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Key Function in Research | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Dicer Enzyme | In vitro processing of pre-miRNAs/shRNAs to verify substrate validity and measure kinetics [32]. | Confirm a novel shRNA design is a true Dicer substrate by observing cleavage into a ~22 nt product [30]. |

| Dicer-Knockout Cell Lines | To study Dicer-independent pathways and isolate the specific functions of Ago2 [34]. | Demonstrate the functionality of AgoshRNAs, which show activity in Dicer-knockout cells, unlike conventional shRNAs [30]. |

| pSilencer Retro System | Viral delivery of shRNA expression constructs for stable, long-term gene silencing, even in hard-to-transfect cells [35]. | Achieve stable knockdown of a target gene in primary human fibroblasts (NHDF-neo cells) to study long-term phenotypic effects [35]. |

| TRBP / PACT Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of the RISC-loading complex to study its composition and assembly dynamics [33] [36]. | Identify novel protein interactors with Ago2 in the presence or absence of miRNAs through co-immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry [34]. |

| Chemically Modified ASOs | To enhance nuclease stability, cellular delivery, and binding affinity for RNase H activation studies [29]. | Compare the potency and longevity of different chemically modified ASOs in triggering RNase H-mediated cleavage of a target mRNA in vivo [29]. |

| Artificial Site-Specific RNA Endonucleases (ASREs) | Engineered tools for precise RNA cleavage, useful for probing RNA function and developing new silencing strategies [31]. | Target and cleave specific mitochondrial-encoded mRNAs, a compartment where traditional RNAi is not functional [31]. |

The choice of silencing pathway—Dicer-dependent, Ago2-centric, or RNase H-mediated—is a fundamental decision that dictates the design, efficacy, and application of gene silencing oligonucleotides. Dicer-dependent strategies (e.g., conventional shRNAs) leverage the cell's natural miRNA biogenesis pathway for robust silencing. In contrast, Dicer-independent designs (e.g., AgoshRNAs) offer a more streamlined pathway directly through Ago2, which can be advantageous for specific therapeutic applications like viral gene therapy [30]. Meanwhile, the RNase H pathway, activated by DNA-like ASOs, operates on a completely different principle but achieves the same final outcome of mRNA degradation [31]. A deep understanding of this cellular machinery, backed by rigorous experimental validation, is paramount for advancing the next generation of oligonucleotide therapeutics from the bench to the clinic.

Therapeutic Applications and Delivery Strategies for Oligonucleotides

In the development of gene silencing oligonucleotides, such as those used in antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and RNA interference (RNAi), two fundamental challenges are overcoming rapid degradation by nucleases and ensuring strong binding to the intended target. Chemical modifications provide a powerful strategy to address these challenges, directly influencing the efficacy, stability, and safety of therapeutic oligonucleotides. This guide objectively compares the performance of major chemical modifications, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed comparison of how different alterations impact nuclease stability and binding affinity, which are critical for designing effective gene silencing therapeutics.

Key Chemical Modifications and Their Mechanisms

Chemical modifications are typically applied to three parts of an oligonucleotide: the phosphate backbone, the ribose sugar, and the nucleobase. Each modification confers distinct properties that can be leveraged to optimize oligonucleotide function.

- Backbone Modifications: The replacement of the non-bridging oxygen with sulfur in the phosphorothioate (PS) backbone is one of the most common modifications. It not only increases resistance to nuclease degradation but also enhances binding to plasma proteins, improving pharmacokinetic properties and cellular uptake [37] [38].

- Sugar Modifications: Modifications at the 2'-position of the ribose sugar, such as 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-fluoro (2'-F), and 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), primarily enhance binding affinity to complementary RNA and increase nuclease resistance. Bulky 2' modifications like 2'-OMe and 2'-MOE provide significant steric hindrance against nuclease activity [39]. Furthermore, bridged nucleic acids (BNAs) like Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA),

- Combinatorial Approaches: Modern oligonucleotide design often employs "gapmer" structures, which combine different modifications within a single molecule. A typical gapmer features a central DNA "gap" region flanked by modified "wings" containing LNA or 2'-modified sugars. This design maximizes RNase H recruitment for target mRNA degradation while ensuring high affinity and stability [37].

The following diagram illustrates the core trade-off between stability and binding affinity in oligonucleotide design, and how hybrid strategies like gapmers integrate the advantages of different modifications.

Comparative Performance Data

A head-to-head comparison of modifications is essential for informed decision-making. The following tables summarize experimental data on nuclease stability and binding affinity from key studies.

Table 1: Nuclease Stability of Chemically Modified Oligonucleotides

| Modification Type | Test System | Key Metric | Performance Summary | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorothioate (PS) | Recombinant CAF1 Deadenylase | Resistance to Degradation | Confers significant resistance against CAF1. | [39] |

| 2'-OMe / 2'-MOE | Recombinant CAF1 Deadenylase | Resistance to Degradation | Provide significantly higher stability against CAF1. | [39] |

| 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) | Recombinant CAF1 Deadenylase | Resistance to Degradation | Limited enhancement of stability at high CAF1 concentration (2.5 μM). | [39] |

| PS/PO Mixed Backbone | Phosphodiesterase I (PDEI), Mouse Serum | Resistance to Exonuclease | Higher stability than full PO; stability depends on PO count and sequence context. | [37] |

| LNA (in Gapmer) | Mouse Liver Homogenate | Metabolic Stability | Significantly enhanced stability compared to unmodified controls. | [37] |

Table 2: Binding Affinity and Functional Activity of Chemically Modified Oligonucleotides

| Modification Type | Target / Protein | Key Metric | Performance Summary | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorothioate (PS) | Poly(A)-Binding Protein (PABP) | Binding Affinity (KD) | Retained PABP binding activity (critical for translation). | [39] |

| 2'-OMe / 2'-MOE | Poly(A)-Binding Protein (PABP) | Binding Affinity (KD) | Abolished PABP binding activity. | [39] |

| 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) | Poly(A)-Binding Protein (PABP) | Binding Affinity (KD) | Abolished PABP binding activity. | [39] |

| LNA (in Gapmer) | Complementary RNA | Target Affinity & Potency | High binding affinity (ΔTm +2 to +8 °C per mod.) and improved gene silencing potency. | [37] [38] |

| 2'-OMe / 2'-MOE | Complementary RNA | Target Affinity | Improved binding affinity relative to unmodified RNA. | [39] [38] |

| PS/PO Mixed Backbone | RNase H1, Immune Proteins | Efficacy & Toxicity | Maintains RNase H1 activity; can reduce immunostimulatory effects and hepatotoxicity. | [37] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the comparative data presented, the experimental methodologies must be clearly detailed.

Nuclease Stability Assay (CAF1 Resistance)

This protocol is used to evaluate the resistance of modified poly(A) tails to deadenylation, a key mRNA decay process [39].

- RNA Substrate Preparation: Synthesize 5'-ATTO488-labeled RNA oligonucleotides. The substrate should consist of a 13-nucleotide unmodified non-poly(A) sequence followed by a 20-nucleotide poly(A) tract with the desired chemical modification pattern (e.g., 50% or 100% modification density).

- Enzymatic Reaction: Incubate the RNA substrate (at a concentration used in the reference study) with 2.5 μM recombinant human CAF1 protein in an appropriate reaction buffer. The reaction should be carried out at 37°C, and aliquots should be taken at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60 minutes).

- Analysis by Denaturing PAGE: Quench the reaction aliquots. Separate the products using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Visualize and quantify the remaining full-length RNA substrate using a fluorescence gel imager. The half-life or percentage of intact RNA remaining at a specific time point serves as the metric for stability.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Binding Assay

This protocol quantitatively measures the binding affinity (KD) between a modified oligonucleotide and a protein like Poly(A)-Binding Protein (PABP) [39].

- Ligand Immobilization: Dilute 5'-biotinylated poly(A) oligonucleotides (e.g., A24 with specific chemical modifications) in HBS-EP+ buffer. Immobilize the ligand onto a Series S streptavidin (SA) sensor chip using standard amine coupling chemistry to achieve an appropriate resonance unit (RU) level.

- Analyte Binding and Kinetics: Dilute the analyte (full-length PABP) in a series of concentrations in running buffer. Inject the analyte over the ligand surface at a constant flow rate (e.g., 30 μL/min) with a contact time of 120 seconds and a dissociation time of 600 seconds. Regenerate the chip surface between cycles with a mild regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0).

- Data Analysis: Double-reference the resulting sensorgrams (subtract both the reference flow cell signal and a buffer blank). Fit the processed data to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model using the SPR evaluation software to determine the association rate (ka), dissociation rate (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

The workflow for these two key experiments is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and materials required to perform the experiments discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Oligonucleotide Stability and Binding Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Modified Oligonucleotides | Substrates for testing stability and binding; potential therapeutics. | PS-oligos, 2'-OMe-oligos, LNA gapmers, custom-synthesized. |

| Recombinant Nucleases | Enzymes for in vitro stability testing. | CAF1 deadenylase, Phosphodiesterase I (PDEI). |

| Biological Matrices | Simulate in vivo degradation environment. | Mouse serum, mouse liver homogenate. |

| SPR Instrumentation & Chips | Label-free, real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions. | Biacore system; Series S Streptavidin (SA) sensor chip. |

| Target Proteins | Analyze the functional binding of modified oligonucleotides. | Recombinant Poly(A)-Binding Protein (PABP), RNase H1. |

| Analytical Chromatography & Electrophoresis | Purity analysis and separation of oligonucleotides and their metabolites. | HPLC, UPLC-MS, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE). |

| PAGE Equipment & Reagents | Separate and visualize oligonucleotide fragments post-degradation assay. | Denaturing polyacrylamide gels, fluorescence imagers. |

The therapeutic application of gene silencing oligonucleotides, such as small interfering RNA (siRNA) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), represents a transformative approach for treating previously undruggable diseases. These therapeutics function by selectively modulating gene expression through RNA interference (RNAi) and related mechanisms, offering the potential for precise, mechanism-based treatments for genetic, oncological, and viral diseases [15] [40]. However, the clinical translation of these powerful therapeutic modalities is critically dependent on effective delivery systems that protect the oligonucleotides from degradation, facilitate tissue-specific targeting, and enable efficient cellular uptake and intracellular release [41] [42].

Among the numerous delivery strategies investigated, three platforms have demonstrated significant clinical success: viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), and GalNAc conjugates. Each system possesses distinct advantages and limitations in terms of delivery efficiency, tissue tropism, manufacturability, and safety profile. Viral vectors, particularly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), offer the potential for long-lasting gene silencing through sustained expression of RNAi triggers. Lipid nanoparticles provide a versatile, non-viral platform capable of encapsulating and protecting large nucleic acid payloads, as exemplified by their successful deployment in COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and the first FDA-approved siRNA therapeutic, patisiran [15] [43]. GalNAc conjugates represent a minimalist approach utilizing direct chemical conjugation of oligonucleotides to N-acetylgalactosamine ligands that specifically target the asialoglycoprotein receptor abundantly expressed on hepatocytes [44] [40].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these three dominant delivery platforms, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental validation methodologies, and suitability for specific research and therapeutic applications. By synthesizing quantitative data from recent studies and outlining standardized experimental protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the necessary information to select appropriate delivery systems for their specific gene silencing objectives.

Platform Comparison: Mechanisms and Performance Metrics

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of key performance metrics for major gene silencing delivery platforms

| Performance Metric | Viral Vectors (AAV) | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | GalNAc Conjugates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Payload | DNA encoding shRNA/miRNA, CRISPR-Cas9 | siRNA, mRNA, ASO, CRISPR components | siRNA, ASO |

| Mechanism of Delivery | Cellular entry via receptor binding, endosomal escape, nuclear import | Endocytosis, endosomal escape via ionizable lipids | Receptor-mediated endocytosis (ASGPR) |

| Delivery Efficiency | High (long-term expression) | Moderate to high (transient) | Very high for hepatocytes |

| Tissue Specificity | Broad tropism (serotype-dependent) | Broad (Liver-lung-spleen dominant; targeting possible) | Highly specific to hepatocytes |

| Onset of Action | Slow (days to weeks) | Rapid (hours to days) | Rapid (hours to days) |

| Duration of Effect | Long-lasting (months to years) | Transient (days to weeks) | Prolonged (weeks to months) |

| Immunogenicity | Moderate to high (pre-existing immunity, cellular immune responses) | Low to moderate (complement activation, anti-PEG immunity) | Very low |

| Manufacturing Complexity | High (cell culture, purification, scalability challenges) | Moderate (chemical synthesis, microfluidic mixing, scalable) | Low (chemical conjugation, highly scalable) |

| Storage Requirements | -80°C (long-term stability concerns) | -20°C to -80°C (lipid stability, cold chain) | Refrigerated or ambient (high stability) |

| Clinical Approval Status | Multiple approvals (e.g., Zolgensma, Luxturna) | Approved (Patisiran, COVID-19 vaccines) | Multiple approvals (Givosiran, Inclisiran) |

Quantitative Efficacy and Biodistribution Data

Table 2: Experimental biodistribution and efficacy data from preclinical and clinical studies

| Platform | Target Tissue/Cell Type | Biodistribution Profile | Silencing Efficiency (Experimental Models) | Effective Dose Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV Vectors | CNS, muscle, liver, retina (serotype-dependent) | Widespread distribution; AAV9 crosses BBB; liver sequestration common | >80% target mRNA reduction in CNS (non-human primates) | 1x1011 to 1x1013 vg/kg |

| LNPs | Liver (hepatocytes, Kupffer cells), spleen, lung | Primarily liver (60-90%); spleen (5-15%); lung (1-5%); can be tuned | 80-95% target knockdown in hepatocytes (mice, NHP) | 0.1-1.0 mg/kg (siRNA) |

| GalNAc Conjugates | Hepatocytes (specific) | >95% liver uptake; minimal extra-hepatic distribution | >90% target protein reduction in clinical trials | 1-10 mg/kg (subcutaneous) |

Platform-Specific Mechanisms and Experimental Methodologies

Viral Vector Delivery Systems

Viral vectors, particularly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), are engineered viral capsids that have been stripped of their replicative capacity and repurposed to deliver genetic material encoding RNAi triggers such as short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) or artificial microRNAs. The mechanism begins with receptor-mediated cell entry, followed by endosomal escape, nuclear entry, and subsequent transcription of the RNAi trigger from the viral genome [42]. The selection of AAV serotype (AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, AAV8, AAV9, etc.) dictates tissue tropism, with different serotypes exhibiting preferential targeting of specific tissues such as CNS (AAV9), muscle (AAV1), or liver (AAV8) [44].

Key Experimental Protocol for Viral Vector Evaluation:

- Vector Production: HEK293 cells are co-transfected with the AAV vector plasmid (containing the shRNA/miRNA expression cassette), rep/cap plasmid (defining serotype), and adenoviral helper plasmid using PEI transfection reagent. Vectors are purified via iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation or affinity chromatography [42].

- Titration: Genome titers are determined by quantitative PCR against standard curves, while infectious titers can be assessed via TCID50 assays.

- In Vivo Administration: Animals receive systemic (intravenous) or local (intracerebral, intramuscular) injections of AAV vectors at doses typically ranging from 1x10^11 to 1x10^13 vector genomes per kilogram (vg/kg).

- Efficacy Assessment: Target gene silencing is quantified via qRT-PCR of mRNA extracts and Western blot analysis of protein levels at predetermined timepoints (weeks to months post-administration).

- Biodistribution Studies: Vector genome distribution is quantified by qPCR of genomic DNA extracted from various tissues, while transgene expression can be visualized using in vivo bioluminescence imaging if a reporter gene is incorporated.

Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Delivery Systems

Lipid nanoparticles represent the most advanced non-viral delivery platform for nucleic acids, with clinical validation through multiple approved therapeutics and vaccines. Modern LNP formulations typically consist of four key components: (1) ionizable lipids that enable encapsulation and facilitate endosomal escape through their protonation in acidic environments; (2) phospholipids that contribute to bilayer structure; (3) cholesterol that enhances membrane integrity and stability; and (4) PEGylated lipids that reduce particle aggregation and opsonization, thereby prolonging circulation time [45] [41]. The mechanism of action involves systemic administration, extended circulatory half-life, cellular uptake via endocytosis, and endosomal escape triggered by the ionizable lipids, culminating in the release of the nucleic acid payload into the cytoplasm.

Key Experimental Protocol for LNP Evaluation:

- LNP Formulation: LNPs are prepared using microfluidic mixing technology where an ethanolic lipid solution (containing ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 at molar ratios typically around 50:10:38.5:1.5) is rapidly mixed with an aqueous solution containing the siRNA or mRNA at a fixed flow rate ratio (typically 3:1 aqueous to ethanol). The ionizable lipid structure (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315) significantly impacts potency [45] [43].

- Characterization: Particle size (typically 70-100 nm) and polydispersity index are measured by dynamic light scattering, ζ-potential by phase analysis light scattering, and encapsulation efficiency using Ribogreen assays after Triton X-100 disruption.

- In Vitro Testing: LNPs are evaluated in hepatocyte cell lines (HepG2, Huh7) or primary hepatocytes using transfection with luciferase-encoding mRNA or target-specific siRNA. Efficiency is quantified via luminescence or qPCR, respectively. Endosomal escape can be visualized using confocal microscopy with labeled lipids and endosomal markers.

- In Vivo Administration: Mice are typically administered 0.1-1.0 mg/kg siRNA or mRNA via intravenous injection. For liver targeting, the particles should have a diameter of <100 nm to facilitate endothelial fenestration.

- Biodistribution Analysis: Using dyes such as DiR or DIR-labeled LNPs, or quantum dots, whole-body distribution can be tracked by in vivo imaging systems (IVIS). Tissue-specific quantification requires HPLC or mass spectrometry analysis of extracted lipids or qPCR of the nucleic acid payload from homogenized tissues.

GalNAc Conjugate Delivery Systems

GalNAc conjugates represent a minimalist, targeted approach for delivering oligonucleotides specifically to hepatocytes. This platform exploits the high-affinity interaction between N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) ligands and the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR), which is abundantly expressed on hepatocytes (approximately 500,000 receptors per cell) and exhibits rapid cycling between the cell surface and intracellular compartments [44] [40]. The typical conjugate structure consists of a fully modified siRNA molecule covalently linked to a triantennary GalNAc ligand via a bifunctional linker. Upon receptor binding, the conjugate undergoes clathrin-mediated endocytosis, followed by endosomal escape and release of the siRNA into the cytoplasm where it engages the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to mediate target mRNA cleavage.

Key Experimental Protocol for GalNAc Conjugate Evaluation:

- Conjugate Synthesis: GalNAc conjugates are synthesized through solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis incorporating stabilized chemical modifications (2'-F, 2'-OMe, PS linkages), followed by solution-phase conjugation to triantennary GalNAc ligands via linkers such as (N-(2-hydroxyethyl)acrylamide) [44].

- In Vitro Binding and Uptake: Receptor binding affinity is quantified using surface plasmon resonance with immobilized ASGPR, or competitive binding assays in hepatocyte cell lines. Cellular internalization is visualized using fluorescently labeled conjugates and confocal microscopy.

- In Vitro Potency:

- Primary hepatocytes (human or mouse) are treated with GalNAc-conjugated siRNAs at concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 100 nM for 48-72 hours.

- Total RNA is extracted, and target gene expression is quantified by qRT-PCR normalized to housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH).

- EC50 values are calculated using non-linear regression analysis of dose-response curves.

- In Vivo Evaluation: