Eliminating DNA Contamination in RNA Preps: A Complete Guide for Accurate Gene Expression Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the critical challenge of genomic DNA contamination in RNA preparations.

Eliminating DNA Contamination in RNA Preps: A Complete Guide for Accurate Gene Expression Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the critical challenge of genomic DNA contamination in RNA preparations. Contaminating DNA is a pervasive issue that can lead to false-positive results in sensitive downstream applications like RT-qPCR and RNA-seq, compromising data integrity. We cover the foundational knowledge of why DNA co-purifies with RNA, explore and compare effective DNase treatment and column-based removal methodologies, offer troubleshooting and optimization strategies for difficult samples, and detail robust validation techniques to confirm complete DNA removal. By synthesizing current best practices, this guide empowers scientists to ensure their RNA samples are truly DNA-free, thereby enhancing the reliability of their transcriptomic data and its applications in biomedical and clinical research.

The Unavoidable Problem: Why Genomic DNA Plagues Your RNA Samples

The pursuit of high-quality, DNA-free RNA is a fundamental prerequisite for reliable gene expression analysis, yet it remains a significant challenge in molecular biology. Despite advances in RNA isolation technologies, contaminating genomic DNA (gDNA) persists as a common problem that can compromise the integrity of sensitive downstream applications like RT-PCR and RNA-Seq. This technical support center is built upon a critical thesis: no single RNA isolation method consistently produces RNA completely free of genomic DNA without targeted intervention [1]. The evidence demonstrates that regardless of the extraction technique employed—from organic extraction to column-based purification—some level of DNA contamination inevitably occurs, necessitating systematic detection and removal protocols. The following troubleshooting guides and FAQs are designed to help researchers navigate this inherent challenge, providing evidence-based strategies to achieve RNA preparations of sufficient purity for even the most demanding applications.

Experimental Evidence: Systematic Comparison of RNA Isolation Methods

Quantitative Evidence of DNA Contamination Across Methods

A comprehensive study evaluating RNA isolated from mouse liver tissue by five different methods demonstrated that all tested techniques resulted in detectable genomic DNA contamination, as evidenced by PCR amplification in minus-RT controls [1].

Table 1: DNA Contamination Detection Across RNA Isolation Methods [1]

| RNA Isolation Method | Example Products | DNA Contamination Detected? |

|---|---|---|

| Single-reagent extraction | TRIzol Reagent, RNA Stat-60 | Yes |

| Glass fiber filter-binding | RNeasy, RNAqueous | Yes |

| Guanidinium thiocyanate/acid phenol | Chomczynski and Sacchi procedure | Yes |

| Centrifugation through CsCl cushion | Traditional ultracentrifugation | Yes |

| Oligo d(T) selection | Poly(A)Pure, FastTrack RNA | Yes |

This foundational evidence establishes that DNA contamination is an inherent limitation across all major categories of RNA isolation methodologies, confirming the necessity of post-isolation DNA removal strategies.

Comparison of Commercial Kits for DNA Contamination

A systematic comparison of six commercial RNA isolation kits using SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells further quantified this problem, revealing significant differences in gDNA carry-over and the effectiveness of DNase treatment [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RNA Isolation Kits and DNase Treatment Efficacy [2]

| Kit Name | Methodology | A260/A280 Ratio | Yield (μg RNA/1E6 cells) | Visible gDNA Contamination Without DNase? | PCR Detection After DNase? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AxyPrep Multisource Total RNA | Spin column | 2.07 | 3.94 ± 0.41 | No | No |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | Spin column | 2.07 | 0.62 ± 0.52 | Yes | Yes |

| EasySpin | Spin column | 2.06 | 1.02 ± 0.54 | Not specified | Not specified |

| Illustra RNAspin Mini | Spin column | 2.13 | 0.09 ± 0.11 | Not specified | Not specified |

| TRIzol Plus | Phenol-based | 1.86 | 0.67 ± 0.80 | Not specified | Not specified |

| E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit II | Phenol-column hybrid | 1.89 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | Not specified | Not specified |

The data highlights that while some kits (particularly the AxyPrep Multisource Total RNA Miniprep) show superior performance with minimal DNA contamination, the effectiveness varies significantly between products. This underscores the importance of both initial kit selection and subsequent DNase treatment for critical applications.

Detection and Removal of Genomic DNA Contamination

Workflow for DNA Contamination Management

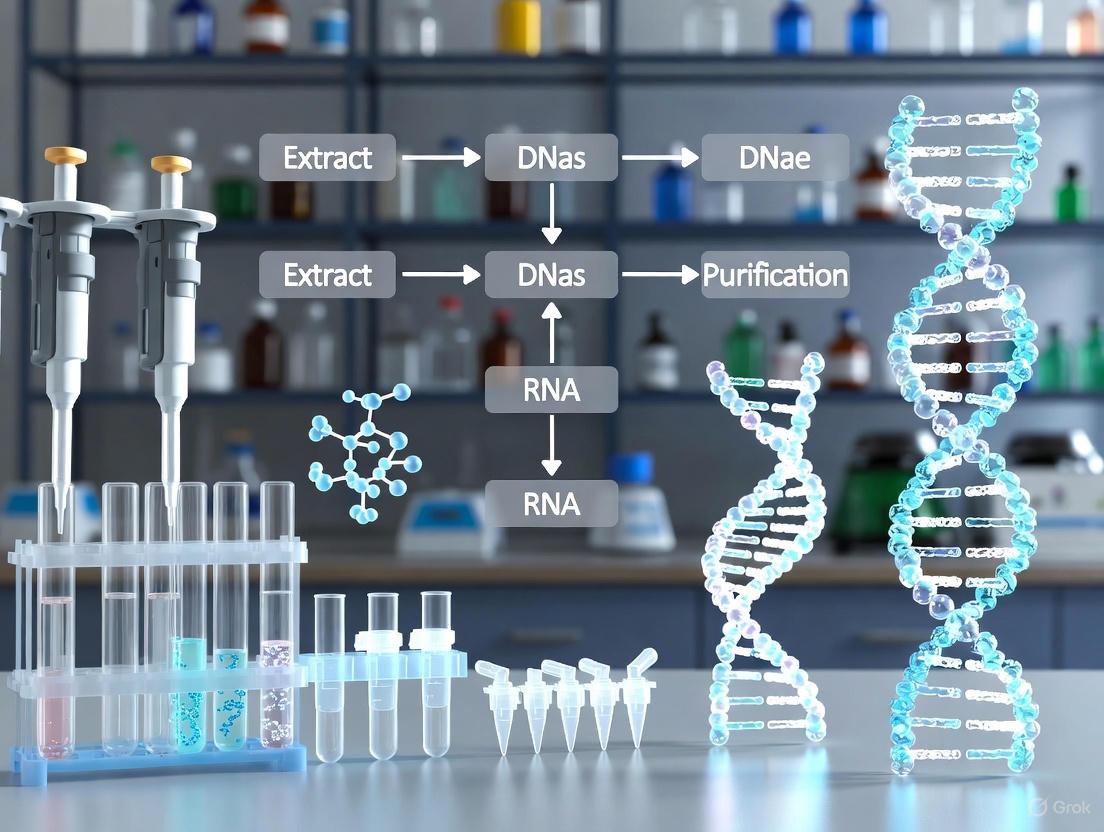

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and procedures for ensuring DNA-free RNA preparations, from initial isolation to final verification:

Methods for Detecting DNA Contamination

Accurate detection of genomic DNA contamination is essential before proceeding with sensitive downstream applications. The following methods provide complementary approaches for identifying gDNA in RNA preparations:

Minus-RT Control PCR: The most critical control for RT-PCR experiments. Amplification of a product from an RNA sample that was not reverse transcribed indicates contamination with amplifiable DNA [1]. This control should be included for every RNA sample in an RT-PCR experiment.

Primer Design Strategy: Designing PCR primers that span intron-exon boundaries can help identify gDNA contamination, as the amplified product from contaminating DNA will include introns and be much larger than the expected cDNA product [1]. However, this approach cannot detect pseudogenes (intron-less processed genes integrated into the genome).

Spectrophotometric Analysis: While A260/A280 ratios below 2.0 can indicate DNA contamination, this method has limited sensitivity. More specialized spectrophotometric assays using fluorescent dyes specific for RNA or DNA can provide better discrimination [3].

Gel Electrophoresis and Fragment Analysis: Genomic DNA contamination can be visualized as a high molecular weight smear or band (>10 kb) on agarose gels, or as a high molecular weight "bump" on a Fragment Analyzer trace [4] [3]. These methods are particularly useful for detecting significant contamination but lack sensitivity for trace amounts.

qPCR with Genomic Targets: The most sensitive detection method, using primer pairs for housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, actin, rDNA loci) that can detect trace amounts of DNA that would escape other detection methods [3]. This approach is essential for applications requiring extremely pure RNA, such as RNA-Seq.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving DNA Contamination Issues

FAQ: Common Scenarios and Evidence-Based Solutions

Q1: My RNA samples show good A260/A280 ratios (>2.0), but I still get amplification in my minus-RT controls. Why does this happen, and how can I resolve it?

This common scenario occurs because spectrophotometric ratios are relatively insensitive to low-level DNA contamination, while PCR can detect minute amounts of DNA [3]. The solution involves implementing a robust DNase treatment protocol:

Protocol: Add 1 μL RNase-free DNase I, 2 μL 10X reaction buffer, 6 μL DEPC-treated H₂O, and 0.5 μL RNase inhibitor to 2 μg RNA in 11 μL DEPC-treated water (total volume 20 μL) [5]. Incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes, followed by 65°C for 20 minutes to inactivate the DNase.

Alternative Solution: Use specialized DNase Treatment & Removal Reagents that include both RNase-free DNase and a unique DNase Removal Reagent that eliminates the enzyme after digestion without messy phenol extractions or risky heat inactivation procedures [1].

Q2: After DNase treatment, my RNA yields are lower. How can I minimize RNA loss during DNA removal?

RNA loss during DNase treatment and cleanup is a common problem. Consider these approaches:

Optimized Removal Reagents: Use integrated systems like the DNA-free DNase Treatment & Removal Reagents, which employ a specialized removal reagent that binds DNase and divalent cations after digestion is complete, requiring only a brief centrifugation step [1]. This avoids the RNA losses associated with phenol:chloroform extraction or additional purification columns.

Modified Protocol: If using column-based cleanups after DNase treatment, extend incubation times during elution to at least 5 minutes or perform two consecutive elutions to maximize RNA recovery [4].

Carrier Enhancement: For very small RNA quantities, add glycogen as a co-precipitant to improve yield visualization and recovery during precipitation steps [6].

Q3: I'm working with lipid-rich tissues (brain, liver) and getting persistent DNA contamination. What specialized approaches can help?

Fatty tissues present particular challenges due to their high lipid content and abundance of complex biomolecules:

Kit Selection: Choose kits specifically designed for challenging tissues. In comparative studies, the AxyPrep Multisource Total RNA Miniprep Kit successfully isolated DNA-free RNA from neuroblastoma cells without additional DNase treatment, while other kits showed persistent contamination [2].

Protocol Modification: For TRIzol-based isolations, add a high-salt precipitation step using 0.25 volumes of isopropanol plus 0.25 volumes of high-salt solution (0.8 M sodium citrate and 1.2 M NaCl) per 1 mL of TRIzol used. This effectively precipitates RNA while maintaining proteoglycans and polysaccharides in soluble form [6].

Q4: How critical is complete DNase removal after treatment, and what's the most effective removal method?

Complete DNase removal is essential because residual enzyme can degrade newly synthesized cDNA in downstream applications [1]. The optimal method depends on your application requirements:

DNase Removal Reagents: Most efficient for routine applications—fast (3 minutes), simple, and minimizes RNA loss [1].

Proteinase K/Phenol-Chloroform: Most rigorous removal but time-consuming, technically demanding, and carries risk of sample loss [1].

Heat Inactivation: Simple but risky—divalent cations in digestion buffer can cause chemically-induced RNA strand scission when heated [1].

Column Purification: Effective but adds expense and processing time [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA-Free RNA

Table 3: Key Reagents for Managing DNA Contamination in RNA Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNase Treatment Systems | DNA-free DNase Treatment & Removal Reagents [1] | Complete system for DNA digestion and enzyme removal |

| RNase-free DNase I | RQ1 RNase-free DNase [5] | Digests DNA without degrading RNA |

| Specialized RNA Kits | RNAqueous-4PCR Kit [1] | Integrated system for RT-PCR-ready RNA |

| Contamination Detection | Minus-RT controls [1] | Essential control for detecting amplifiable DNA |

| Rapid DNase Removal | DNase Removal Reagent [1] | Binds and removes DNase after treatment |

| Organic Removal | Phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol [5] | Traditional protein and enzyme removal |

| Inhibition Prevention | RNase Out [5] | Protects RNA from degradation during processing |

The evidence unequivocally supports the thesis that DNA contamination is an inevitable consequence of RNA isolation, regardless of the method employed. Rather than seeking a perfect isolation technique, researchers should adopt a systematic approach that assumes contamination will occur and implements appropriate detection and removal strategies. This includes: (1) selecting isolation methods validated for your specific sample type; (2) implementing sensitive detection controls appropriate for your downstream application; (3) applying optimized DNase treatment protocols; and (4) verifying successful DNA removal before proceeding to critical experiments. By acknowledging the inevitability of DNA contamination and implementing these evidence-based practices, researchers can consistently generate DNA-free RNA suitable for even the most sensitive applications in gene expression analysis and diagnostic development.

FAQ: DNA Contamination in RNA Preparations

1. Why is genomic DNA contamination a problem in RNA-based experiments? DNA contaminating RNA preparations can serve as a template during PCR, leading to false-positive signals in sensitive downstream applications like RT-PCR and RNA-seq. This can obscure true gene expression data and result in inaccurate conclusions [1].

2. Can I rely on my RNA isolation kit to completely remove genomic DNA? No. No RNA isolation method consistently produces RNA entirely free of genomic DNA without the use of a dedicated DNase treatment step. This includes single-reagent extraction methods, glass fiber filter-binding methods, and guanidinium thiocyanate/acid phenol-chloroform extractions [1].

3. What is the best way to check for DNA contamination in my RNA sample? The most reliable method is to perform a "minus-RT" control. In this control, the RNA sample is run through the PCR protocol without the reverse transcription step. If a PCR product is generated, it was amplified from contaminating DNA, not the RNA of interest [1]. While designing primers to span intron-exon boundaries can help, it is not foolproof due to the existence of intron-less pseudogenes [1].

4. My RNA-seq data shows DNA contamination. How can I address this bioinformatically? While some alignment and counting processes may filter out reads mapping to non-genic regions, variable levels of DNA contamination can complicate differential expression analysis [7]. Specialized tools and R packages are being developed to tackle this issue. If contamination is suspected, you can:

- Re-analyze with alignment filters: Standard alignment and counting may ignore intergenic reads.

- Explore specialized tools: Investigate new software designed to estimate and correct for DNA contamination in sequencing data [7].

- Note: Overly aggressive correction can also remove genuine signals, so results should be interpreted with caution [7].

5. How does extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA) differ from common genomic DNA contamination? eccDNA is a natural form of circular DNA derived from chromosomal DNA but existing independently in the nucleus [8]. Unlike random genomic DNA fragments, eccDNA is a biologically meaningful molecule involved in gene regulation, cancer progression, and other cellular functions. Its circular nature and potential to carry full genes make it a distinct entity from the linear genomic DNA fragments that typically contaminate RNA preps [9]. Standard DNase treatments may not distinguish between contaminating linear DNA and biologically relevant circular eccDNA.

Troubleshooting Guide: Preventing and Removing Genomic DNA Contamination

Problem: Persistent DNA contamination in RNA samples after standard isolation.

Solution: Implement a rigorous DNase treatment protocol followed by safe enzyme removal.

Detailed Protocol: DNase Treatment and Removal

This protocol ensures complete DNA digestion without risking RNA degradation [1].

Materials:

- RNase-free DNase I

- 10X DNase Reaction Buffer

- DNase Removal Reagent (or spin-column cleanup kit)

- RNase inhibitor (optional)

Steps:

- DNase Digestion: For a 20 µL reaction, combine 2 µg of RNA, 1 µL of RNase-free DNase I, 2 µL of 10X reaction buffer, and RNase-free water. Add 0.5 µL of RNase inhibitor for extra protection [5].

- Incubate: Incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes [5]. Some protocols recommend doubling the standard incubation time or enzyme units for stubborn contamination [10].

- Inactivate/Remove DNase: This is a critical step. Avoid simple heat inactivation in the presence of Mg²⁺, as it can cause RNA degradation [1]. Use one of these methods:

- Preferred - DNase Removal Reagent: Add the reagent, incubate for 2 minutes at room temperature, and centrifuge. The DNase and ions are pelleted, leaving clean RNA in the supernatant [1].

- Alternative - Spin-Column Purification: Pass the reaction mixture through an RNA clean-up column to bind the RNA and wash away the DNase [10] [4].

- Quality Control: Always perform a "minus-RT" control PCR to confirm the success of the DNA removal.

Problem: DNA contamination is discovered post-sequencing in RNA-seq data.

Solution: Assess the level of contamination and consider bioinformatic correction.

- Assessment: Use quality control tools to estimate the percentage of reads mapping to intergenic or intronic regions [7].

- Action:

- If contamination is low and uniform across samples, standard alignment and quantification with DESeq2 may be sufficient, as counting is often restricted to exonic regions [7].

- If contamination is high and variable, consider using specialized software to subtract the contamination signal. Be aware that this may reduce the power to detect differentially expressed genes [7].

- For critical experiments, the most robust solution is to repeat the experiment with a new, rigorously DNase-treated RNA sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA-Free RNA Work

The following table details key reagents for preventing and removing DNA contamination.

| Item | Function | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNase-free DNase I | Enzymatically digests contaminating DNA in RNA samples. | Must be certified RNase-free; requires Mg²⁺/Ca²⁺ for activity; sold separately or in kits [1] [10]. |

| DNase Removal Reagent | Rapidly inactivates and removes DNase after digestion. | Prevents RNA degradation; faster and safer than phenol-chloroform extraction [1]. |

| RNA Clean-up Kit (Spin Column) | Purifies RNA after DNase treatment to remove enzyme and salts. | Essential if not using a dedicated removal reagent; also removes other contaminants [10] [4]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA from degradation during DNase treatment. | Added to digestion reaction for extra security with valuable samples [5]. |

| "minus-RT" Control Primers | Detects DNA contamination in RNA samples. | Primers designed to span an intron can help distinguish PCR products from cDNA vs. genomic DNA [1]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Sample to Contamination-Free RNA

The diagram below illustrates the integrated workflow for obtaining high-quality, DNA-free RNA, incorporating both experimental and computational checkpoints.

Understanding eccDNA: A Specialized Source of Signal

In the context of DNA contamination, it is crucial to be aware of extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA). These are circular DNA molecules derived from chromosomal DNA but physically separate from it [8]. They range in size from hundreds of base pairs to megabases and can carry entire genes, including oncogenes in cancer [11] [9].

Biogenesis and Relation to DNA Damage: A primary mechanism for eccDNA formation involves errors in DNA repair. When DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) occur, they can be repaired by pathways like nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ). If two intrachromosomal DSBs happen close together, the repair machinery can incorrectly circularize the excised fragment, creating eccDNA [11] [9]. This means that cellular stress and DNA damage, which can be common in experimental models like cancer cell lines, actively generate these molecules.

Why It Matters: Unlike random genomic contamination, eccDNA is a biologically functional entity. In RNA-seq experiments, transcripts originating from genes amplified on eccDNA (like ecDNA in cancer) are genuine biological signals and should not be filtered out as contamination [8] [9]. Distinguishing between technical DNA contamination and meaningful eccDNA-derived signals requires careful experimental design and data interpretation, often needing specialized sequencing methods like Circle-seq for definitive identification.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing DNA Contamination in RNA Studies

1. How does genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination cause false positives in RT-qPCR?

gDNA contamination in RNA samples is a frequent cause of false positives in RT-PCR-based analyses. During reverse transcription and qPCR, primers can amplify contaminating gDNA sequences if they are present. This risk is significantly higher for long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) like MALAT1, NEAT1, and NORAD, which often lack intron-exon junctions. Without these junctions, it is impossible to design primers that distinguish the mature RNA transcript from the genomic DNA template, leading to co-amplification and false positive signals [12].

2. Why are lncRNA studies particularly vulnerable to DNA contamination?

Many well-studied lncRNAs have no introns in their sequences. A review of the literature shows that the expression levels of many lncRNAs are often evaluated by RT-qPCR without a DNase treatment step. When researchers tested this using MALAT1 as a model lncRNA, they found that results were highly affected by gDNA contamination. The inclusion of a DNase treatment step was determined to be absolutely necessary to avoid false positive results, a finding that can be extrapolated to other lncRNAs without exons [12].

3. What are the best methods for decontaminating laboratory surfaces to prevent DNA carryover?

Studies evaluating decontamination efficiency have found large differences between cleaning strategies. The most effective methods for removing contaminating DNA from surfaces like plastic, metal, and wood are sodium hypochlorite (bleach) solutions and certain commercial agents like Trigene and Virkon [13] [14]. A comparison of cleaning strategies is provided in Table 1 below.

4. How can I identify contamination in my qPCR experiments?

One of the most common ways to monitor for contamination is to use "No Template Controls" (NTCs). These wells contain all qPCR reaction components except for the DNA template. If these wells show amplification, it indicates contamination. If the contamination is from a contaminated reagent, all NTCs will show similar amplification. If the contamination is random, like from an aerosol, only some NTCs will amplify, and at different cycle threshold (Ct) values [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DNase Treatment of RNA Samples to Prevent gDNA False Positives

The following protocol, adapted from research on MALAT1, is essential for specific lncRNA detection [12].

- Reaction Setup: In a nuclease-free tube, combine the following:

- ≤ 200 ng/μL input RNA

- 1 μL TURBO DNase Buffer

- 0.4 U DNase I enzyme

- Incubation: Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Add 1 μL of DNase Inactivation Reagent and incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Separation: Centrifuge the tube at 10,000 × g for 1.5 minutes. Carefully transfer the supernatant (containing the treated RNA) to a fresh, nuclease-free tube.

- Verification: To confirm complete DNA degradation, perform a PCR targeting your gene of interest (e.g., MALAT1) using the DNase-treated RNA as a template without the reverse transcription step. The absence of amplification confirms successful DNA removal.

Protocol 2: Establishing a Contamination-Minimized qPCR Workflow

Good laboratory practice is essential to avoid contamination in sensitive qPCR experiments [15].

- Physical Separation: Establish separate, dedicated areas for different stages of work:

- Pre-PCR Area: For sample preparation, reagent preparation, and qPCR setup.

- Post-PCR Area: For qPCR amplification and analysis of products.

- These areas should have dedicated equipment (pipettes, centrifuges, lab coats) and consumables. Maintain a one-way workflow from pre- to post-PCR areas.

- Use of Protective Equipment: Always wear gloves and change them frequently, especially if contamination is suspected. Use aerosol-resistant filtered pipette tips.

- Surface Decontamination: Regularly clean work surfaces and equipment in the pre-PCR area with a 10-15% fresh bleach solution (sodium hypochlorite). Allow it to sit for 10-15 minutes before wiping down with de-ionized water. Note that bleach is unstable, so fresh dilutions should be made weekly [15] [13].

- Reagent and Sample Management: Aliquot all reagents to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles and cross-contamination of stock solutions. Store samples separately from reagents and kits.

- Enzymatic Control (Optional): Use a master mix containing Uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG). When combined with dUTP in the PCR mix, UNG can degrade carryover contamination from previous amplification products before the thermal cycling begins [15].

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for a robust, contamination-aware qPCR experiment:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Efficiency of Cleaning Strategies for DNA Decontamination on Various Surfaces

This table summarizes data from a study that quantified the percentage of mitochondrial DNA recovered from different surfaces after cleaning with various agents, compared to a no-treatment control [13].

| Cleaning Agent | Plastic (% Recovery) | Metal (% Recovery) | Wood (% Recovery) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA | |||

| No-treatment control | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Ethanol (70%) | 26.0 | 21.0 | 20.0 |

| DNA Remover | 5.8 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| Sodium hypochlorite (0.4%) | < 0.3 | < 0.3 | < 0.3 |

| Trigene (10%) | < 0.3 | < 0.3 | < 0.3 |

| Virkon (1%) | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| Whole Blood (Cell-Contained DNA) | |||

| No-treatment control | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Ethanol (70%) | 46.0 | 43.0 | 27.0 |

| Sodium hypochlorite (0.4%) | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| Virkon (1%) | < 0.8 | < 0.8 | < 0.8 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Preventing and Managing DNA Contamination

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| DNase I Enzyme | Enzymatically degrades contaminating genomic DNA in RNA samples prior to reverse transcription, crucial for studying intron-less lncRNAs [12]. |

| Uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) | An enzyme included in some qPCR master mixes that degrades carryover contamination from previous PCR products (containing dUTP) before amplification begins [15]. |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | A potent chemical decontaminant for laboratory surfaces. Solutions with 1-2% active hypochlorite effectively destroy amplifiable DNA [13] [14]. |

| Aerosol-Resistant Filtered Tips | Prevent the accidental introduction of aerosols into pipette shafts, minimizing cross-contamination between samples during liquid handling [15]. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | A critical quality control reaction containing all PCR components except the template RNA/DNA. Amplification in the NTC indicates contamination [15]. |

FAQs: Addressing Critical Concerns on DNA Contamination

Q1: Why is genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination a particularly critical issue for long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) research, as in the MALAT1 case study?

gDNA contamination is a critical issue because many well-studied lncRNAs, including MALAT1, NEAT1, NKILA, and NORAD, lack introns (i.e., they are mono-exonic) [16] [12]. Primers designed for their detection by RT-qPCR will inevitably bind to contaminating gDNA sequences, as there are no exon-intron junctions to target across. This leads to false-positive signals, as the PCR amplifies the gDNA contaminant alongside, or instead of, the intended cDNA target [12]. Without a DNase treatment step, results on the expression of these lncRNAs are highly unreliable [16].

Q2: What are the primary sources of gDNA contamination in RNA samples?

Contamination primarily arises during sample preparation. Key sources include:

- Co-extraction: gDNA is routinely co-extracted with RNA during standard isolation protocols [12].

- Incomplete DNase Digestion: Residual gDNA remains if a DNase treatment step is omitted or performed inefficiently [17].

- Carry-over during Library Prep: In RNA-seq, residual gDNA can be carried into sequencing libraries because reverse transcriptase can use DNA as a template, and the resulting DNA products are processed alongside cDNA [18].

- Cross-Contamination: Aerosolized DNA from other samples in the lab environment can contaminate reagents or samples during qPCR setup. This is a major concern for highly sensitive techniques [15].

Q3: How can I detect gDNA contamination in my RNA samples or sequencing data?

Several methods can be used for detection:

- No Template Controls (NTCs): In RT-qPCR, include wells containing all reaction components except the RNA template. Amplification in these wells indicates contamination of your reagents or primers with gDNA or amplicons [15].

- Spectrophotometry: While not specific for gDNA, abnormal A260/280 ratios can sometimes indicate contamination [19].

- Bioanalyzer/TapeStation: gDNA contamination can appear as a high molecular weight smear or as a distinct peak on an electrophoretogram [20].

- RNA-seq Mapping Metrics: The percentage of reads mapping to intergenic regions (IR%) is a key metric for gDNA contamination. Tools like Picard Tools, Qualimap, and the CleanUpRNAseq R package can calculate this and other diagnostic statistics [18].

Q4: My RNA-seq data is already generated and I suspect gDNA contamination. Can I correct for it computationally?

Yes, bioinformatic correction is possible. The CleanUpRNAseq R/Bioconductor package is specifically designed to identify and correct gDNA contamination in RNA-seq data [18]. It offers multiple correction methods for both unstranded and stranded data, helping to improve the accuracy of gene expression quantification and downstream differential expression analysis without the need to re-sequence samples [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Solving DNA Contamination

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| False positives in RT-qPCR for mono-exonic genes/lncRNAs | Primers amplifying contaminating gDNA due to lack of exon-intron junctions [16] [12]. | Incorporate a rigorous DNase I treatment step during RNA purification (on-column or in-solution) prior to cDNA synthesis [16] [12]. |

| High molecular weight smear on RNA gel/bioanalyzer | Insufficient shearing or removal of gDNA during homogenization and purification [19] [20]. | Optimize homogenization to shear gDNA thoroughly (e.g., bead beating). Perform an off-column DNase treatment for samples rich in gDNA [19]. |

| Amplification in No Template Controls (NTCs) | Contaminated reagents (primers, water, master mix) or aerosol contamination in the lab [15]. | Aliquot reagents. Use aerosol-resistant filter tips. Physically separate pre- and post-PCR areas. Decontaminate workspaces and equipment with 10-15% bleach solution [15]. |

| High intergenic read percentage in RNA-seq | gDNA carried over and sequenced in the RNA-seq library [18] [17]. | Use CleanUpRNAseq for in-silico correction [18]. For future preps, ensure complete DNase digestion and use poly(A) selection, which is less susceptible to gDNA contamination than rRNA depletion [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: The MALAT1 Contamination Case Study

This protocol outlines the key experimental steps used to validate the effect of gDNA contamination on MALAT1 detection [12].

Objective

To quantify the false-positive signal in MALAT1 lncRNA detection caused by gDNA contamination and demonstrate the necessity of a DNase treatment step.

Materials

- Sample Types: Plasma, primary tissue samples (e.g., from NSCLC patients).

- RNA Extraction Kit: miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Advanced Kit or RNeasy Mini Kit.

- DNase I Enzyme: TURBO DNase (Ambion Life Technologies) including buffer and inactivation reagent.

- Reverse Transcription Kit: High-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit.

- qPCR Reagents: SYBR Green master mix, specific primers for MALAT1 and a control gene (e.g., B2M).

Methodology

- Sample Collection and RNA Extraction:

- Critical Step: DNase Treatment:

- Split the extracted RNA into two aliquots: one for DNase treatment and one as an untreated control.

- Treatment Group: In a DNase-free tube, combine ≤200 ng/μL RNA, 1 μL TURBO DNase Buffer, and 0.4U DNase I enzyme. Incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes [12].

- Add 1 μL of DNase inactivation reagent, incubate for 5 minutes, and centrifuge at 10,000× g for 1.5 minutes. Carefully transfer the supernatant (purified RNA) to a new tube [12].

- cDNA Synthesis:

- Reverse transcribe the DNase-treated and untreated RNA into cDNA using the high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit.

- Include a negative control (no reverse transcriptase enzyme) for the untreated RNA sample to check for gDNA contamination [12].

- qPCR Amplification and Analysis:

- Perform qPCR using primers specific for the mono-exonic MALAT1 lncRNA and a control gene (e.g., B2M) that has exons and introns, allowing primers to be designed across a junction [12].

- Compare the Ct values for MALAT1 and the control gene between the DNase-treated and untreated samples.

Expected Results

- In untreated samples, MALAT1 will be detected with a low Ct value, suggesting high expression.

- In DNase-treated samples, the MALAT1 signal should be significantly reduced or eliminated, while the signal for the control gene (B2M) remains unchanged. This confirms that the initial MALAT1 signal was a false positive due to gDNA contamination [16] [12].

This table summarizes findings from a systematic study where known amounts of gDNA were spiked into RNA.

| gDNA Contamination Level | Library Prep Method | Effect on Gene Expression Quantification | Number of False DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% (DNase Treated) | Poly(A) Selection | Minimal | Baseline |

| 0.1% | Poly(A) Selection | Minimal | Low |

| 1% | Poly(A) Selection | Altered for low-abundance transcripts | Increased |

| 10% | Poly(A) Selection | Significantly altered | High |

| 0% (DNase Treated) | Ribo-Zero (rRNA depletion) | Minimal | Baseline |

| 0.1% | Ribo-Zero (rRNA depletion) | Begins to alter profiling | Moderate |

| 1% | Ribo-Zero (rRNA depletion) | Significantly altered | High |

| 10% | Ribo-Zero (rRNA depletion) | Severely altered / Clusters with untreat. | Very High |

This table highlights the pervasiveness of contamination in public repositories.

| Data Source / Study | Type of Contamination | Prevalence / Impact |

|---|---|---|

| GTEx (V7) Dataset | Pancreas & esophagus-enriched genes (e.g., PRSS1, KRT4) in non-native tissues [21]. | ~40% of samples affected; led to numerous false eQTL assignments [21]. |

| Various RNA-seq Studies | Genomic DNA (gDNA) reads from incomplete removal [18]. | gDNA contamination levels ranged from 0.7% to 22.7% in human Ribo-Zero libraries [18]. |

| SEQC/MAQC-III Consortium | DNA contamination in reference RNA samples [18]. | Spotted in commercial reference RNA and project samples, affecting data integrity [18]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Enzymatically degrades contaminating genomic DNA in RNA samples. Can be used on-column during purification or in-tube after elution [22] [12]. |

| miRNeasy / RNeasy Kits | For simultaneous extraction of total RNA (including small RNAs) from serum, plasma, and tissues. Provides a clean RNA template suitable for sensitive downstream assays [12]. |

| TURBO DNase | A potent, recombinant DNase effective for removing gDNA from challenging samples. Often includes an easy-to-use inactivation reagent [12]. |

| Uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) | An enzyme included in some qPCR master mixes to prevent carryover contamination from previous PCR amplifications by degrading uracil-containing DNA templates [15]. |

| CleanUpRNAseq R Package | A bioinformatics tool for detecting and correcting the effects of gDNA contamination in existing RNA-seq data, salvaging valuable datasets [18]. |

| Aerosol-resistant Filter Tips | Essential for preventing cross-contamination of samples and reagents during liquid handling, a key best practice in qPCR and RNA work [15]. |

FAQ: Why might my primers still amplify genomic DNA even when they span an exon-exon junction?

This occurs when a significant portion of the primer's 3' end is complementary to a sequence within a single exon of the genomic DNA. Even if the 5' end does not bind, the polymerase can still extend from the annealed 3' end, leading to a false-positive amplification product [23]. This partial annealing negates the primary advantage of using junction-spanning primers.

FAQ: What are the proven methods to completely eliminate genomic DNA contamination?

Relying solely on primer design is often insufficient. A multi-layered approach combining robust primer design with physical removal of genomic DNA is recommended. The following table summarizes the effectiveness of common decontamination methods based on experimental data:

| Method | Protocol Summary | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I Treatment | Treat purified RNA samples with DNase I, followed by enzyme inactivation or removal [24]. | Most effective method; treatment with TURBO DNase increased ΔCt (no-RT vs +RT) from 3.43 to 12.99, indicating near-complete DNA removal [24]. |

| Compaction Agents | Use cationic molecules (e.g., Spermidine) to selectively precipitate double-stranded DNA from an RNA solution [25]. | With 500 μM Spermidine, genomic DNA was undetectable (Ct ≥ 12.6) after 40 PCR cycles, while mRNA Ct increased by only 5 cycles, showing strong DNA-selectivity [25]. |

| Column-Based Purification | Use kits (e.g., PureLink, MagMAX) that incorporate a DNase digestion step on the purification column [24]. | Effective when integrated with on-column DNase digestion; without it, ΔCt was as low as 1.27, but digestion made DNA undetectable [24]. |

The following workflow illustrates this integrated, multi-layered defense strategy:

FAQ: How can I design better junction-spanning primers to minimize genomic amplification?

Advanced primer design tools and specific parameter tuning are critical. The limitations of early tools have been addressed by newer software that incorporates experimental validation.

The table below compares the capabilities of modern primer design tools:

| Tool Name | Key Features for Avoiding gDNA | Species Availability | Notable Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| ExonSurfer [26] [27] | Designs primers spanning junctions; performs genomic DNA BLAST; avoids common SNPs. | Human, Mouse, Rat, Zebrafish, A. thaliana, D. melanogaster, O. sativa | Open-source; automatically selects optimal junctions; provides end-to-end design with specificity filtering. |

| Ex-Ex Primer [23] | Generates primers from established/hypothetical junctions; parameters fine-tuned with experimental validation. | Human, Mouse, Rat | Experimentally validated; helps circumvent gDNA contamination in RT-PCR. |

| Primer-BLAST [28] | Option for "Primer must span an exon-exon junction"; checks primer specificity against a selected database. | Broad (uses NCBI databases) | Integrates Primer3 with BLAST for specificity; widely used and trusted. |

When designing primers, adhere to these experimentally-supported parameters:

- Junction Placement: Ensure the 3' end of the primer (approximately 5-10 bases) is complementary to the second exon. This minimizes the chance of stable annealing to a single exon in gDNA [23] [29].

- Primer Length: Keep primers between 18–24 nucleotides [29].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): Aim for a Tm of 60–64°C, with forward and reverse primers within 1–2°C of each other [29] [30].

- Amplicon Size: Design a short amplicon, ideally 75–150 bp. This improves PCR efficiency and makes any gDNA-derived product (which would be much larger) less likely to amplify efficiently [29] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA-Free RNA Research

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Role in Preventing gDNA Contamination |

|---|---|---|

| TURBO DNA-free Kit [24] | DNase I digestion | Highly effective for removing gDNA from purified RNA samples; includes a reagent to remove the enzyme post-digestion. |

| Cells-to-CT Kit [24] | Cell lysis & nucleic acid preparation | Integrates rapid cell lysis with on-spot DNase I digestion, eliminating the need for RNA purification. |

| PureLink / MagMAX Kits [24] | RNA purification | Column-based kits that include an optional on-column DNase digestion step for efficient gDNA removal during purification. |

| Spermidine (Compaction Agent) [25] | Selective nucleic acid precipitation | A cationic molecule that selectively precipitates double-stranded gDNA from an RNA solution, offering a nuclease-free alternative. |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (*_m1) [24] | qPCR detection | Pre-designed assays where the probe spans an exon-exon junction, ensuring detection of only spliced cDNA and not gDNA. |

DNA Removal in Action: Comparing DNase Treatment and Innovative Kit Technologies

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How can RNA be treated to remove residual DNA? RNase-free DNase treatment of the RNA can reduce DNA to undetectable levels. A common protocol involves combining 1 µg total RNA, 1 µL 10X DNase I buffer, 1 µL Amplification Grade DNase I (1 unit/µL), and DEPC-treated water to a 10 µL reaction volume. This is incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature and inactivated by adding 1 µL of 25 mM EDTA followed by heating for 10 minutes at 65°C [31].

2. What is the difference between regular DNase I and Amplification Grade DNase I? Amplification Grade DNase I is subjected to an extra final HPLC purification step to remove traces of RNases, making it suitable for sensitive applications like RT-PCR. It is supplied at 1 unit/µL with a dedicated buffer and EDTA. Regular DNase I is supplied at a much higher concentration (5-15 mg/mL or 50-375 U/µL) and does not come with its own buffer [31].

3. Are DNase I products RNase-free? Most commercial DNase I products are guaranteed free of RNase activity. However, some versions (e.g., Cat. No. 18047-019) are not tested for RNase and are recommended primarily for protein applications. For demanding applications like RT-PCR, it is advised to use a grade specifically certified as RNase-free, such as Amplification Grade DNase I [31].

4. When can DNase treatment be omitted? DNase treatment can be considered when using RNA extraction methods that minimize gDNA carry-over (e.g., acidic phenol/chloroform extraction) or when using 3' mRNA-Seq library prep methods that rely on poly(A) stretches for priming, as these pick up less gDNA background. It may also be omitted in some targeted sequencing experiments where the genomic loci for primer binding are distant from the transcript regions [3].

5. How do I know if my RNA sample is contaminated with DNA? The most sensitive method is to run a "minus-RT" control in an RT-PCR experiment. If a PCR product is generated from an RNA sample that was not reverse transcribed, it indicates contaminating DNA. Other methods include analyzing optical density ratios (a 260/280 value below 2 can indicate DNA contamination), agarose gel electrophoresis (looking for a high molecular weight band), or using a Fragment Analyzer [1] [3].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| DNA persists after treatment | Incomplete digestion or inactivation of DNase I [1] | Ensure optimal digestion conditions (buffer, time, temperature). Use a reliable inactivation method (e.g., EDTA chelation + heat, or a DNase Removal Reagent) [31] [1]. |

| RNA degradation after treatment | RNase contamination in DNase I preparation or harsh inactivation [1] | Use certified RNase-free DNase I. Avoid heating RNA in the presence of divalent cations; instead, use EDTA to chelate Mg²⁺ before heat step or use a DNase Removal Reagent [31] [1]. |

| Poor RT-PCR/Yield | Carryover of DNase I or inactivation reagents [1] | DNase I can degrade newly synthesized cDNA. Ensure complete removal/inactivation of DNase I after the digestion step. If using EDTA, note that it can inhibit downstream enzymes; the chelation capacity may need to be saturated with additional ions [1]. |

| Low DNase I Activity | Suboptimal reaction buffer [32] | DNase I requires Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ for optimal activity. Ensure the reaction buffer contains these divalent cations (e.g., 2 mM MgCl₂ and 0.1 mM CaCl₂) [32]. |

| Enzyme adherence to tube walls [32] | DNase I is a "sticky" enzyme. Use RNase-free microfuge tubes for reactions to minimize activity loss [32]. |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol: DNase I Treatment of RNA [31] This protocol is designed to remove up to 1 µg of DNA from an RNA sample.

- Reaction Setup: Combine the following in a nuclease-free microcentrifuge tube:

- 1 µg of total RNA

- 1 µL of 10X DNase I Reaction Buffer (e.g., 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 20 mM MgCl₂, 500 mM KCl)

- 1 µL of Amplification Grade DNase I (1 unit/µL)

- DEPC-treated water to a final volume of 10 µL.

- Incubation: Mix gently and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Inactivation: Add 1 µL of 25 mM EDTA (final concentration 2.3 mM) to chelate the Mg²⁺ ions.

- Heat Inactivation: Incubate the mixture at 65°C for 10 minutes to inactivate the DNase I.

- Proceed: The treated RNA is now ready for downstream applications like RT-PCR.

Protocol for Heavily Contaminated RNA [32] For RNA with severe DNA contamination or when treating more than 10 µg of RNA.

- Dilution: Dilute the RNA sample to a concentration of approximately 100 µg/mL of nucleic acid.

- Reaction Setup: For a 25–100 µL reaction, use 2 units of DNase I per ~10 µg of RNA.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes.

- Inactivation and Clean-up: Inactivate and remove the DNase I using a method such as the DNA-free DNase Removal Reagent, phenol:chloroform extraction, or column purification [32] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| Amplification Grade DNase I | An endonuclease purified to be RNase-free, specifically for digesting contaminating DNA in RNA preps for sensitive downstream applications [31]. |

| 10X DNase I Reaction Buffer | An optimized buffer (typically containing Tris-HCl, MgCl₂, KCl, and sometimes CaCl₂) providing the ideal ionic conditions and pH for maximum DNase I activity [31] [32]. |

| DNase Inactivation Reagent | A unique reagent (e.g., a resin) that rapidly sequesters and removes DNase I and divalent cations after digestion, preventing RNA degradation and avoiding hazardous phenol extraction [1]. |

| EDTA (25 mM Solution) | A chelating agent used to inactivate DNase I by binding the Mg²⁺ ions essential for its enzymatic activity. It is often included in inactivation protocols [31]. |

Workflow: DNase I Treatment and Verification

The diagram below outlines the key steps and verification methods for ensuring DNA-free RNA.

Within the broader context of research on removing DNA contamination from RNA preparations, DNase I enzyme serves as a fundamental tool for ensuring accurate molecular biology results. This technical support center addresses the critical experimental challenges researchers face when implementing DNase protocols, particularly focusing on maintaining complete enzymatic activity while ensuring the enzyme preparations are free of RNase contamination. DNase I nonspecifically cleaves DNA to release 5'-phosphorylated di-, tri-, and oligonucleotide products, making it indispensable for degrading contaminating DNA after RNA isolation, preparing RNA for sensitive downstream applications like RT-PCR, and conducting specialized techniques such as DNase I footprinting to identify protein binding sequences on DNA [32]. The efficacy of these applications depends entirely on proper protocol optimization and understanding the enzyme's behavior under various experimental conditions.

Understanding DNase I: Mechanism and Applications

Biochemical Properties and Cleavage Specificity

DNase I is a 37,000 Dalton endonuclease derived from bovine pancreas that degrades double-stranded DNA to produce 3'-hydroxyl oligonucleotides [33]. The enzyme requires divalent cations for activity, and its specificity depends on which divalent cation is present. In the presence of Mg²⁺, DNase I nicks each strand of double-stranded DNA independently, generating random cleavage sites [33]. The digestion of heterogeneous double-stranded DNA typically yields dinucleotides (60%), trinucleotides (25%), and oligonucleotides, with the smallest substrate being a trinucleotide [32].

Although commonly described as nonspecific, DNase I does exhibit some sequence preference, showing sensitivity to minor groove structure and favoring cleavage of purine-pyrimidine sequences [32]. However, it cuts at all four bases in heterogeneous double-stranded DNA, with specificity for a given base typically varying no more than 3-fold [32]. The enzyme also demonstrates reduced activity on non-standard DNA structures: its specific activity for single-stranded DNA is approximately 500 times less than for double-stranded DNA, while activity on RNA-DNA hybrids is less than 1-2% of that for double-stranded DNA [32].

Research Applications

- DNA Contamination Removal: Elimination of trace to moderate amounts of genomic DNA from RNA preparations to prevent false positives in RT-PCR [32] [34]

- DNase Footprinting: Identification of protein binding sequences on DNA through protection patterns from DNase digestion [32]

- Cell Culture Applications: Prevention of cell clumping when handling cultured cells [32]

- Library Preparation: Creation of fragmented DNA sequence libraries for in vitro recombination reactions [32]

- Assay Validation: Verification that signals in DNA quantification assays specifically measure DNA rather than non-DNA components [33]

Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table summarizes key reagents required for optimized DNase experiments:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for DNase Protocols

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase-free DNase I | Degrades DNA contaminants in RNA samples | Certified free of RNase activity; essential for RNA work | DNA removal from RNA preps; sample clean-up prior to RT-PCR [32] [35] |

| resDetect DNase Activity Assay Kit | Quantitative DNase detection | FRET-based; rapid 30-min assay; sensitivity: 3.9×10⁻⁵ U | Detecting DNase contamination in buffers/reagents [36] |

| RNase Alert Kit | Tests for RNase contamination | Single-step 30-min assay; works with various RNases | Verifying RNase-free status of DNase preparations [35] |

| Threshold Total DNA Assay | Quantitates contaminant DNA | Validates DNA removal efficiency | Biopharmaceutical quality control; DNase qualification [33] |

| NAxtra Magnetic Nanoparticles | Nucleic acid isolation | Cost-effective; suitable for low cell inputs (down to single cells) | High-throughput NA purification from limited samples [37] |

| DNase I Buffer (10X) | Optimal enzyme activity | Contains Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺, Tris pH 7.5 | Standard digestion conditions; compatible with various samples [32] |

Optimized DNase Protocols and Methodologies

Standard DNase I Treatment for RNA Samples

This protocol is suitable for removing up to 1 µg of DNA from RNA samples in a 25-100 µL reaction volume [32]:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute RNA sample to approximately 100 µg/mL nucleic acid concentration before treatment. For severely contaminated RNA preparations (DNA >10 µg/mL), dilute to 100 µg/mL total nucleic acid concentration [32].

- Reaction Setup:

- Use 2 units of DNase I per 10 µg of RNA

- Prepare 1X DNase I Buffer from 10X stock (final concentration: 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM CaCl₂)

- Adjust reaction volume to 25-100 µL

- For heavily contaminated samples, use 4-6 units of DNase I and extend incubation to 60 minutes [32]

- Incubation: 37°C for 30 minutes (standard) or 60 minutes (heavy contamination)

- DNase Inactivation: Several methods are available:

- DNase Removal Reagent: Add reagent, incubate, and pellet by centrifugation (most recommended) [32]

- Heat Inactivation: 75°C for 10 minutes (may cause RNA degradation in presence of divalent cations) [32]

- Phenol Extraction: Effective but risks RNA loss and residual phenol inhibition of downstream applications [32]

DNase I Qualification Protocol

Before using a new lot of DNase I for critical applications, qualify its activity using this procedure [33]:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare DNase I at 2500 U/mL in storage buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM dithioerythritol, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 50% glycerol). Aliquot and store at -20°C [33].

- Reaction Setup: Test three levels of DNase I (25, 50, and 100 units) in duplicate with appropriate controls:

- Prepare tubes with 0.5 mL Zero Calibrator with and without DNA spike (50 pg double-stranded DNA)

- Add DNase I stock (10 µL for 25 U, 20 µL for 50 U, 40 µL for 100 U)

- Add MgCl₂ to 5 mM final concentration

- Incubation and Processing:

- Incubate 3 hours at 37°C

- Heat samples at 105°C for 15 minutes, then cool on ice

- Add EDTA to chelate free Mg²⁺ ions

- Analyze denatured samples with Total DNA Assay

- Interpretation: The lowest DNase I level that reduces DNA spike by at least 90% while allowing proper filtration is the optimum concentration [33].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points in DNase experimentation:

Fluorescence-Based DNase Activity Assessment

Advanced detection methods utilize FRET-based assays for sensitive DNase activity measurement [36] [38]:

- Principle: A fluorophore-labeled DNase substrate remains non-fluorescent until cleaved by DNase activity, producing a gradually enhanced fluorescence signal proportional to enzyme concentration and activity [36].

- Procedure:

- Add 90 µL working DNase substrate solution to 96-well plate

- Add 10 µL DNase I standards or test samples

- Incubate in fluorometer collecting real-time data at 1-minute intervals for 30 minutes at 37°C

- Measure fluorescence at ex/em = 535/565 nm

- Applications: Quantitative determination of DNase I in environmental samples, biological materials, and molecular biology reagents [36].

Troubleshooting Common DNase Experimental Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Table 2: DNase Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete DNA digestion | Insufficient DNase units; suboptimal buffer conditions; sample too concentrated | Qualify DNase activity; ensure Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ present; dilute sample to ~100 µg/mL nucleic acid | Use recommended 2 U/10 µg RNA; include cation requirements in buffer [32] |

| RNase contamination | DNase preparation contaminated with RNase | Use certified RNase-free DNase; test with RNaseAlert Kit | Verify RNase-free status before critical RNA work [35] |

| Poor downstream PCR | Residual DNase activity; incomplete inactivation | Use DNase Removal Reagent instead of heat; add EDTA to chelate cations | Avoid heat inactivation in presence of divalent cations [32] |

| High background in assays | DNase adhesion to tubes; small DNA fragments | Use recommended tube types; qualify digestion efficiency | Use RNase-free microfuge tubes; up to 50% activity loss to tube walls [32] |

| Variable activity across samples | Buffer incompatibility; inhibitory components | Increase DNase concentration for inhibitory samples; ensure consistent Mg²⁺ levels | Some proteins inhibit DNase I; may require higher units or overnight incubation [33] |

Critical Technical Considerations

Cation Requirements: Contrary to some beliefs, DNase I is not active in buffers containing Mg²⁺ yet lacking Ca²⁺. The minimal activity observed in Ca²⁺-free buffers is due to synergistic activation by contaminating Ca²⁺. EGTA addition at concentrations above Ca²⁺ levels but below Mg²⁺ levels inhibits DNase I by at least 1000-fold [32].

Ionic Strength Effects: DNase I exhibits optimal activity in buffers containing Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ without additional salts. When NaCl or KCl concentration increases from 0 to 30 mM, activity drops more than 2-fold [32].

Enzyme Adhesion: DNase I is a "sticky" enzyme that can adhere to container walls. In some microfuge tubes and 96-well plates, up to 50% of input DNase activity can adhere to container walls within 10 minutes. Use RNase-free microfuge tubes specifically recommended for DNase digestions [32].

Sample Compatibility: The optimal amount of DNase I must be determined for different sample types. Some proteins may inhibit DNase I activity, requiring higher enzyme concentrations or extended incubation times, potentially overnight for complete digestion [33].

Advanced Applications and Methodologies

Integration with Novel Extraction Technologies

Emerging technologies complement traditional DNase applications:

- Magnetic Nanoparticle Isolation: The NAxtra-based method enables simple, rapid, inexpensive purification of total nucleic acids, RNA, or DNA down to the single-cell level without carrier RNA. Automated processing allows handling of 96 samples within 12-18 minutes, providing a cost-effective alternative to commercial kits [37].

- High-Throughput Genome Release: Mechanical disruption methods using specialized 96-well plates and shear applicators can release genomic DNA without traditional extraction buffers, enabling rapid preparation of PCR-ready DNA from fungal spores and other challenging samples within minutes [39].

Quantitative Assessment in Pharmaceutical Applications

In biopharmaceutical settings, DNase I is used with the Total DNA Assay to:

- Validate that assay signals specifically measure DNA rather than non-DNA components

- Confirm that observed assay inhibition stems from small fragment DNA rather than protein or buffer interference [33]

These applications require rigorous DNase qualification and careful attention to reaction conditions, particularly Mg²⁺ concentrations and appropriate EDTA chelation after digestion [33].

Optimized DNase protocols balancing complete DNA degradation with preservation of RNA integrity are fundamental to successful molecular biology research. By understanding the enzyme's biochemical requirements, implementing proper qualification procedures, utilizing appropriate controls, and selecting validated reagents, researchers can effectively overcome common experimental challenges. The continued development of complementary technologies like magnetic nanoparticle extraction and high-throughput genome release further enhances our ability to work with challenging samples while maintaining the critical DNA removal capabilities that DNase I provides. Through careful attention to the technical details outlined in this support document, researchers can ensure reliable, reproducible results in their investigations of gene expression and nucleic acid biology.

Column-Based DNA Removal is a integrated purification strategy that leverages the binding properties of silica-based membranes or magnetic beads to separate RNA from other cellular components, concurrently incorporating a dedicated deoxyribonuclease (DNase) digestion step to eliminate genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination. This methodology is critical because virtually all RNA isolation methods, including single-reagent extraction and glass fiber filter-binding techniques, co-purify trace amounts of gDNA, which can lead to false-positive results in sensitive downstream applications like RT-PCR and RNA-Seq [1] [40]. The on-column treatment efficiently removes this contaminating DNA, ensuring the integrity of gene expression data, particularly for targets like long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that lack intron-exon junctions and are highly susceptible to gDNA-driven false signals [40].

The workflow typically involves binding RNA to the column matrix under specific buffer conditions, performing an on-column DNase digestion to degrade DNA, washing away impurities, and finally eluting purified, DNA-free RNA. This approach minimizes sample handling and reduces the risk of RNase contamination and RNA degradation compared to in-solution digestion methods [41].

FAQs: Addressing Common Research Queries

1. Why is a dedicated DNA removal step necessary, even with specialized RNA extraction kits? No RNA isolation method consistently produces RNA completely free of genomic DNA without a DNase treatment [1]. Contaminating gDNA is a frequent cause of false positives in RT-PCR-based analyses, as it can serve as an amplification template [1] [40]. This is a particular concern for quantifying certain lncRNAs (e.g., MALAT1, NEAT1) that lack introns, making it impossible to design primers that distinguish between cDNA and gDNA templates [40]. Including a DNase treatment step is essential to avoid compromised data and erroneous conclusions.

2. What are the advantages of on-column DNase treatment versus in-solution digestion? On-column digestion offers several key benefits:

- Reduced RNA Loss and Degradation: The process occurs after the RNA is bound and protected on the column matrix, minimizing sample manipulation and contact with potential RNases [41].

- Streamlined Workflow: The DNase enzyme is simply washed away in subsequent steps, avoiding the need for additional purification methods like phenol:chloroform extraction or heat inactivation, which can be time-consuming, lead to sample loss, or damage the RNA [1].

- Effectiveness: It provides an efficient method for removing DNA while minimizing potential degradation [41].

3. My RNA samples still show DNA contamination after on-column DNase treatment. What should I do? If contamination persists, consider these troubleshooting steps:

- Verify Protocol Execution: Ensure the correct DNase I reaction buffer was used and that the incubation was performed at the proper temperature and duration (typically 15-30 minutes at room temperature or 37°C) [42] [41].

- Assess Sample Type: Tissues rich in gDNA, such as spleen, may require a more rigorous DNase treatment. For challenging samples, a second DNase treatment or a high-activity, room-temperature-stable DNase kit used in-solution after the initial purification may be necessary [20].

- Check for Inhibitors: Residual salts or guanidine from the lysis buffer can inhibit DNase activity. Ensure wash buffers contain ethanol and perform the recommended number of wash steps prior to the DNase treatment to remove these inhibitors [42] [20].

- Confirm Removal: Always include a "no-reverse transcriptase" (-RT) control in downstream RT-PCR experiments to test for the presence of contaminating DNA [41] [1].

4. How does gDNA contamination specifically impact RNA-Seq data analysis? gDNA contamination in RNA-Seq libraries can introduce significant biases:

- Altered Transcript Quantification: It can lead to inaccurate quantification of low-abundance transcripts, making them appear more expressed than they are. This inflates the background signal for non-expressed genes and can lead to false positives in differential expression analysis [43] [17].

- Disrupted Normalization: The random background of DNA-derived reads can throw off global normalization methods, affecting the entire dataset's integrity [43].

- False Discovery of Novel Elements: Contamination can lead to the misidentification of genomic sequences as novel transcribed elements, such as new long non-coding RNAs [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low RNA Yield | Incomplete elution from the column. | Ensure elution buffer is applied directly to the center of the membrane to saturate it completely. Consider using a larger elution volume or a second elution [42]. |

| DNA Carryover | Insufficient DNase digestion or presence of inhibitors. | Ensure reagents are mixed thoroughly. Verify that wash steps before digestion are complete to remove inhibitors. For difficult samples, increase DNase incubation time or use a higher activity DNase [42] [20]. |

| RNA Degradation | RNase contamination during the procedure. | Use RNase-free tips, tubes, and reagents. Work quickly on a clean bench and wear gloves. Keep columns covered when not in use [42]. |

| Low A260/230 Ratio (Salt Carryover) | Residual guanidine salts or wash buffer components. | Perform additional wash steps with the provided wash buffer (containing ethanol). Ensure the column does not contact the flow-through. If reusing collection tubes, blot the rim to remove residual liquid before re-centrifugation [42] [4]. |

| Inhibition in Downstream Applications | Ethanol or salt carryover from wash buffers. | Perform a final "dry spin" of the column (empty) to remove residual ethanol before elution. Ensure the eluate does not contact the flow-through [42] [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Correction

Protocol 1: Standard On-Column DNase Digestion

This is a generalized protocol for performing DNase treatment directly on a RNA purification column.

Materials:

Method:

- Bind RNA to the column per the manufacturer's instructions and wash as normal.

- Prepare the DNase I digestion mix on ice: Combine 10 µl of 10x DNase I Reaction Buffer, 5 µl (or 1 unit/µg RNA) of RNase-free DNase I, and 85 µl of nuclease-free water for a 100 µl total reaction volume [41].

- Apply the digestion mix directly onto the center of the silica membrane in the column.

- Incubate at room temperature (15-25°C) or 37°C for 15 minutes.

- Add wash buffer to the column and centrifuge to stop the reaction and remove the DNase enzyme.

- Proceed with the remaining wash steps and final RNA elution as directed by the kit protocol.

Protocol 2: In-Solution DNase Treatment for Stubborn Contamination

For samples with persistent gDNA contamination, a more rigorous in-solution treatment after initial RNA isolation may be required.

Materials:

- RNase-free DNase I

- 10x DNase I Reaction Buffer

- 25 mM EDTA

- Nuclease-free water

- Thermostatic water bath or heat block

Method:

- Thaw the purified RNA sample on ice.

- For up to 2 µg of RNA, combine the RNA, 2 µl of 10x DNase I Reaction Buffer, and 1 unit of DNase I per 1-2 µg of RNA. Adjust the final volume to 20 µl with nuclease-free water [41].

- Incubate the sample for 5-10 minutes at 37°C [41].

- Inactivate the DNase I by adding 2.5 µl of 25 mM EDTA and incubating for 5-10 minutes at 65-75°C [41].

- Centrifuge the sample briefly and place on ice. The RNA can now be used directly or cleaned up again using an RNA cleanup kit to remove EDTA and ions if they are suspected to inhibit downstream reactions [1].

Protocol 3: Detecting gDNA Contamination with a "-RT" Control

This control is essential for validating the success of DNA removal.

- Method:

- When setting up an RT-PCR experiment, include a control reaction for each RNA sample that contains all components except the reverse transcriptase enzyme [41] [1].

- Substitute the reverse transcriptase volume with nuclease-free water.

- Run this "-RT" control through the subsequent PCR amplification alongside your experimental samples.

- Interpretation: A PCR product in the "-RT" control indicates the presence of contaminating gDNA in your RNA sample, as the product was amplified from DNA, not cDNA. The absence of a band confirms successful DNA removal [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Spin Columns | Binds RNA under high-salt conditions, allowing contaminants and DNA to be washed through. | The foundation of column-based purification. Modern kits often integrate DNA removal steps directly into the protocol [44]. |

| RNase-Free DNase I | Degrades both single-stranded and double-stranded DNA by hydrolyzing phosphodiester bonds. | Critical for effective DNA removal. Must be RNase-free to prevent RNA degradation. Available from suppliers like NEB and ThermoFisher [42] [1]. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based Kits (e.g., MagMAX, NAxtra) | Silica-coated magnetic beads bind RNA, enabling high-throughput automation on platforms like KingFisher. | Offer scalability, repeatability, and reduced processing time. Effective for removing interfering nucleic acids from complex samples like AAV preparations [44] [37]. |

| DNase Inactivation Reagents | Removes or inactivates DNase post-digestion without harmful heat or phenol. | A unique reagent in some kits (e.g., DNA-free) that binds DNase and cations after digestion, enabling a clean, quick inactivation by centrifugation [1]. |

| Specialized Kits with Integrated DNA Removal (e.g., RNAqueous-4PCR) | Provides a complete system from isolation to DNA removal, ensuring RNA is ready for RT-PCR. | Designed for maximum convenience and reliability, including all necessary reagents for DNA removal in a single kit [1]. |

Quantitative Impact of gDNA Contamination

Research has systematically quantified the effects of gDNA contamination on RNA-seq data, providing critical insights for data interpretation.

Table 1: Impact of gDNA Contamination on RNA-Seq Analysis (Adapted from BMC Genomics [17])

| gDNA Added to Total RNA | Library Prep Method | Effect on Gene Expression Profiling | Number of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% (DNase-treated control) | Poly(A) Selection & Ribo-Zero | Baseline profile. | Baseline. |

| 0.01% - 0.1% | Poly(A) Selection | Minimal to no significant effect. | Approximately constant. |

| 0.01% - 0.1% | Ribo-Zero | Begins to affect clustering; more sensitive to contamination. | Increasing number of DEGs. |

| 1% - 10% | Poly(A) Selection | Significant fluctuations; libraries cluster separately. | Marked increase. |

| 1% - 10% | Ribo-Zero | Major disruption; profiling is highly skewed. | Large, concentration-dependent increase. |

Key Findings from the Data:

- Ribo-Zero vs. Poly(A) Selection: Ribosomal RNA depletion methods (Ribo-Zero) are significantly more sensitive to gDNA contamination than poly(A) selection methods [17].

- Low-Abundance Transcripts are Most Affected: Over 94% of genes whose measured expression was artificially correlated with gDNA contamination were low-abundance transcripts (log2 FPKM < 0) [17]. This contamination can raise false discovery rates in differential expression analysis.

- Residual DNA Post-DNase: The same study estimated that even after standard DNase treatment, total RNA can retain approximately 1.8% residual gDNA contamination [17], underscoring the need for effective removal protocols.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Problems and Solutions with Phenol-Free DNA Removal

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| DNA contamination persists after treatment | Insufficient DNase I activity or contact time | Increase DNase I concentration to 1 unit per 1-2 µg RNA and ensure 10-minute incubation at 37°C [41]. |

| RNA degraded after DNase treatment | RNase contamination or improper heat inactivation | Use certified RNase-free DNase I. Inactivate with 25 mM EDTA and heat at 65-75°C for 10 minutes [41]. |

| Low RNA yield after column cleanup | Inhibitor carryover from silica columns | Dilute eluted sample or use precipitation-based purification to avoid column-derived inhibitors [45]. |

| Incomplete DNA removal from surfaces | Short contact time or low temperature | For surfaces, use DNA/RNA-ExitusPlus with 10-20 minute contact time; increase temperature to 50-60°C for large contaminations [46]. |

| Skewed spectrophotometer ratios (260/230) | Chemical contaminant carryover, such as ethanol | Vent the open sample tube on the lab bench for 20 minutes and re-measure. For RNA, ensure 260/230 ratio >1.5 [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of phenol-free DNA removal reagents?

Phenol-free reagents, such as DNA/RNA-ExitusPlus, offer significant safety and practical benefits. They are non-toxic to humans, non-corrosive to laboratory equipment, and do not produce toxic fumes. Their ready-to-use formulation, often with a color indicator, allows for easy application on workstations and equipment. Furthermore, they achieve complete DNA/RNA degradation via non-enzymatic, catalytic processes, eliminating the risk of residual contamination that can falsify PCR results [46].

Q2: How can I effectively remove DNA from an RNA sample without using phenol?

The most common and effective phenol-free method is treatment with RNase-free DNase I. A standard protocol involves incubating the RNA sample with DNase I (1 unit per 1-2 µg of RNA) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 100 mM Tris-HCl, 25 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM CaCl₂, pH 7.6) at 37°C for 5-10 minutes [41]. The DNase I can then be inactivated by adding 25 mM EDTA and heating at 65-75°C for 10 minutes [41]. Alternatively, many modern RNA isolation kits incorporate an on-column DNase digestion step, which is highly efficient and minimizes sample handling and potential RNase degradation [41].

Q3: My downstream enzymatic reactions are inhibited after a column-based cleanup. What should I do?

Research has shown that commercial silica columns can elute low levels of an unidentified substance that inhibits subsequent enzymatic reactions [45]. To resolve this, you can:

- Dilute the eluent: A higher dilution factor can reduce the concentration of the inhibitor to a level that no longer affects your enzyme [45].

- Switch purification methods: Employ an inhibitor-free precipitation-based purification method. A novel approach using chaotropic salts combined with alcohol or polyethylene glycol (PEG) can achieve simultaneous protein removal and nucleic acid precipitation, effectively avoiding this issue [45].

Q4: Is heat inactivation alone sufficient to stop DNase I activity?

While a common practice, heat inactivation alone can be risky. For critical applications, a more robust method is recommended. The most reliable protocol involves chelating the divalent cations (Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺) that DNase I requires for activity. This is done by adding EDTA (to a final concentration of 5-20 mM) before or concurrently with the heat inactivation step (65-75°C for 10 minutes) [41]. Some researchers also use Proteinase K treatment followed by a cleanup step to degrade the DNase I completely [41].

Q5: How do I validate that DNA contamination has been successfully removed from my RNA sample?

The standard method is to perform a "no-reverse transcriptase" control (-RT control) during your RT-PCR analysis. In this control, the reverse transcriptase enzyme is omitted from the reaction mix. If a PCR product is still amplified, it indicates the presence of contaminating DNA, not the target RNA. A successful DNA removal treatment will result in no amplification in the -RT control [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DNA Removal from RNA Samples

| Reagent | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I, RNase-free | Enzymatically degrades both single- and double-stranded DNA [41]. | The gold-standard enzyme for DNA removal; requires Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ for activity [41]. |

| DNA/RNA-ExitusPlus | Non-enzymatic chemical reagent that degrades DNA/RNA on surfaces and equipment [46]. | Ready-to-use spray; non-toxic, non-corrosive, and contains a color indicator [46]. |

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., GITC, GHCl) | Enable simultaneous protein denaturation and nucleic acid precipitation in inhibitor-free protocols [45]. | Key component in novel single-step purification methods that avoid silica column inhibitors [45]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ ions, effectively inactivating DNase I [41]. | Critical for stopping DNase I activity after digestion without relying solely on heat [41]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease used to digest and remove DNase I enzyme after treatment [41]. | Used as an alternative or supplement to EDTA/heat inactivation, often followed by a cleanup step [41]. |

Experimental Workflow: Phenol-Free DNA Contamination Removal

The following diagram illustrates the primary workflows for removing DNA contamination from RNA samples using innovative, phenol-free methods.

DNA Removal Method Decision Workflow

When selecting a DNA removal strategy, the optimal choice depends on the nature of your sample and the required purity. The following decision diagram guides you through the selection process.