Beyond the Genetic Code: Discovering Novel DNA and RNA Modifications and Their Therapeutic Potential

The epitranscriptome and epigenome are rapidly expanding frontiers in molecular biology.

Beyond the Genetic Code: Discovering Novel DNA and RNA Modifications and Their Therapeutic Potential

Abstract

The epitranscriptome and epigenome are rapidly expanding frontiers in molecular biology. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on the discovery of novel DNA and RNA modifications. We explore the foundational biology of these chemical marks, from recently identified phage DNA arabinosylation to diverse RNA modifications like m6A and ac4C. The content delves into cutting-edge detection methodologies such as LIME-seq, discusses challenges in therapeutic targeting and detection specificity, and validates the clinical potential of these modifications as biomarkers and drug targets. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this article serves as a critical resource for understanding how novel nucleic acid modifications are reshaping therapeutic development for cancer, genetic disorders, and infectious diseases.

The Expanding Universe of Nucleic Acid Modifications: From Basic Mechanisms to Novel Discoveries

The regulation of gene expression extends beyond the DNA sequence itself, encompassing dynamic and reversible chemical modifications that form additional layers of cellular control. These regulatory mechanisms are classified into two complementary fields: epigenetics, which involves modifications to DNA and histone proteins that influence chromatin architecture and DNA accessibility, and epitranscriptomics, which encompasses chemical modifications to RNA molecules that fine-tune their metabolism, function, and stability [1] [2].

Understanding these modifications is crucial for a comprehensive view of cellular biology, as they regulate key processes including development, cellular differentiation, and stress responses. Furthermore, their dysregulation is implicated in a broad spectrum of human diseases, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [3] [1]. This overview details the known modifications within the epigenome and epitranscriptome, their functional consequences, the methodologies for their study, and their relevance to disease and drug discovery, providing a foundation for the discovery of novel modifications.

The Epigenome: A Landscape of DNA and Histone Modifications

The epigenome constitutes a heritable, yet reversible, layer of information that controls gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. It functions through several interconnected mechanisms, primarily involving direct chemical modification of DNA and histone proteins [1].

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is the most extensively studied epigenetic mark. It involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue, primarily within cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5-mC). This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B responsible for de novo methylation, and DNMT1 maintaining methylation patterns during DNA replication [4] [1].

Genomic DNA methylation patterns are not uniform. CpG islands—regions with a high frequency of CpG sites—are often found in gene promoters and are typically unmethylated, allowing for gene expression. In cancer, a hallmark of epigenetic dysregulation is the simultaneous occurrence of global genomic hypomethylation, which can lead to genomic instability and oncogene activation, and localized hypermethylation of CpG islands in the promoters of tumor suppressor genes, leading to their silencing [1]. The methylation process is dynamic, with the Ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of enzymes catalyzing the oxidation of 5-mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) and other derivatives, initiating active DNA demethylation pathways [1].

Histone Modifications

Histones, the core protein components of nucleosomes, are subject to a wide array of post-translational modifications on their N-terminal tails, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination [4] [1]. These modifications, often called the "histone code," are written, read, and erased by specialized enzymes and can either activate or repress transcription depending on the specific mark and its genomic context.

- Acetylation: Catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), the addition of an acetyl group to lysine residues neutralizes the positive charge of histones, relaxing chromatin structure (euchromatin) and promoting gene expression. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove these marks, leading to chromatin compaction (heterochromatin) and gene silencing [1].

- Methylation: Histone methyltransferases (HMTs) add methyl groups to lysine or arginine residues. The functional outcome is highly context-dependent; for example, methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me) is associated with active genes, while methylation at H3K27 (H3K27me) is repressive. This process is reversed by histone demethylases (KDMs) [1].

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Modifications and Their Functional Roles

| Modification Type | Chemical Group | Enzymes (Writers/Erasers) | General Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | Methyl group | DNMTs (Writers), TET enzymes (Erasers) | Gene silencing, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation |

| Histone Acetylation | Acetyl group | HATs (Writers), HDACs (Erasers) | Chromatin relaxation, transcriptional activation |

| Histone Methylation | Methyl group | HMTs (Writers), KDMs (Erasers) | Transcriptional activation or repression, dependent on specific residue |

The Epitranscriptome: Chemical Modifications of RNA

The epitranscriptome refers to the collection of all post-transcriptional chemical modifications to cellular RNA, representing a rapidly expanding field in molecular biology. Over 300 distinct RNA modifications have been identified, though only a subset has been well-characterized in messenger RNA (mRNA) [2] [3]. These modifications add a dynamic and reversible layer of regulation that influences nearly every aspect of RNA metabolism, including splicing, nuclear export, translation, stability, and decay [2].

Major mRNA Modifications

Similar to epigenetics, epitranscriptomic modifications are installed by "writer" enzymes, removed by "eraser" enzymes, and interpreted by "reader" proteins that dictate the functional outcome [2] [3].

- N6-methyladenosine (m⁶A): This is the most abundant and well-studied internal mRNA modification. It is dynamically regulated by a methyltransferase complex (writer) whose core includes METTL3 and METTL14, and is removed by demethylases (erasers) such as FTO and ALKBH5 [2] [3]. Readers proteins from the YTHDF family recognize m⁶A and influence mRNA fate, typically promoting transcript decay or modulating translation. m⁶A is enriched near stop codons and in 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) and is critical for neurodevelopment, stem cell differentiation, and the cellular stress response [2] [3] [5].

- Pseudouridine (Ψ): This is an isomer of uridine where the uracil base is linked to the ribose sugar via a carbon-carbon bond instead of a nitrogen-carbon bond. This "fifth ribonucleotide" increases mRNA stability and can influence translation fidelity. Its role in therapeutic mRNA design is crucial, as it helps evade innate immune recognition [2].

- 5-Methylcytosine (m⁵C): Methylation of cytosine in mRNA, catalyzed by enzymes like NSUN2, influences RNA export, translation efficiency, and stability [2] [3].

- N1-methyladenosine (m¹A): This positively charged modification can affect RNA secondary structure and translation. It has been implicated in diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by promoting the aggregation of proteins like TDP-43 [3].

- mRNA Cap Modifications: The 5' end of eukaryotic mRNA is capped with a modified guanine nucleotide (m⁷G). Further methylation can occur on the initial transcribed nucleotides, forming cap1 (m⁷GpppNm) and cap2 (m⁷GpppNmNm) structures. These modifications are essential for transcript stability, efficient translation initiation, and immune evasion [2].

Table 2: Prevalent mRNA Modifications and Their Characteristics (Ranked by PubMed Citation Prevalence)

| Modification | PubMed Prevalence (Rank) | Writer Enzymes | Eraser Enzymes | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N6-methyladenosine (m⁶A) | Highest [2] | METTL3-METTL14 complex | FTO, ALKBH5 | mRNA decay, translation, splicing, neurodevelopment |

| Pseudouridine (Ψ) | High [2] | Pseudouridine synthases (PUS) | (Not readily reversible) | mRNA stability, immune evasion, translation |

| 5-Methylcytosine (m⁵C) | High [2] | NSUN2, DNMT2 | TET enzymes? | RNA export, translation, stability |

| A-to-I Editing (Inosine) | High [2] | ADAR enzymes | (Not readily reversible) | Proteome diversity, RNA splicing, immune tolerance |

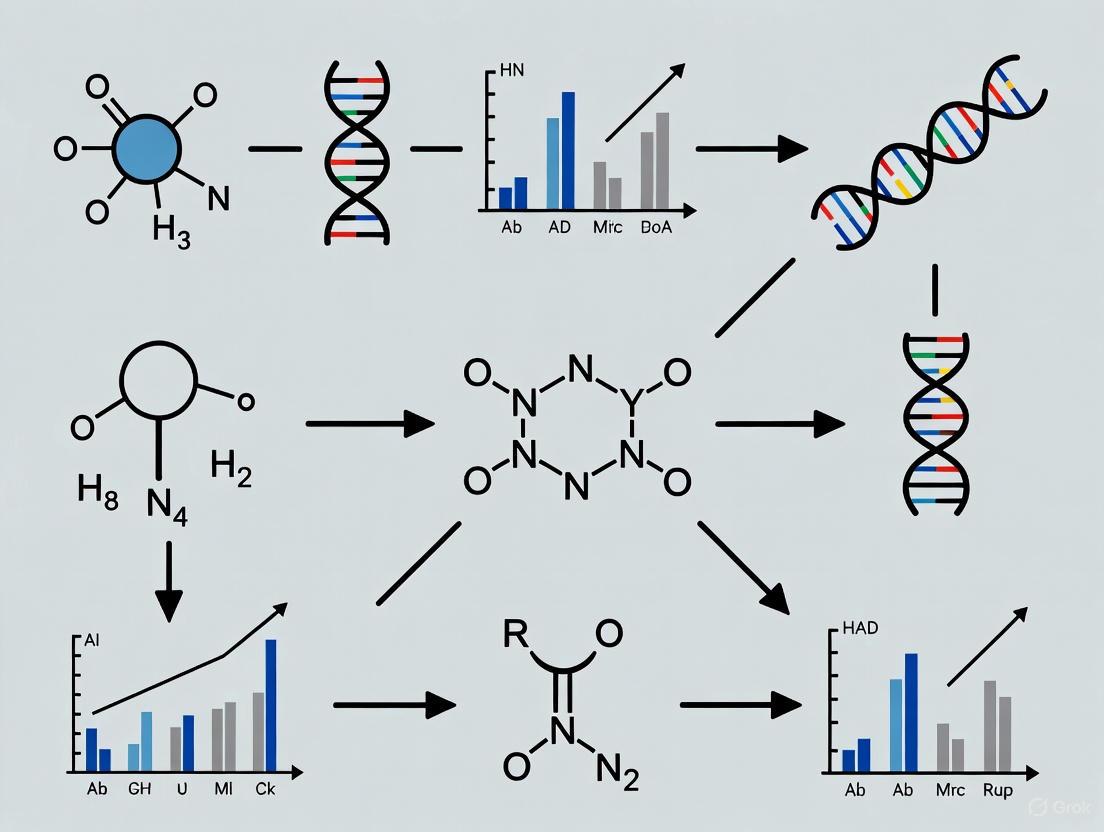

Diagram 1: The Writer-Reader-Eraser Paradigm of the Epitranscriptome. This diagram illustrates the dynamic cycle of RNA modifications, exemplified by m⁶A, Ψ, and m⁵C. Writer enzymes install the mark, reader proteins interpret it to dictate functional outcomes, and eraser enzymes remove the modification, allowing for rapid cellular responses [2] [3].

Methodologies for Mapping Modifications

Advancements in detection technologies have been instrumental in driving discoveries in both epigenetics and epitranscriptomics. The choice of method depends on the modification of interest, the required resolution, and the available input material.

Epigenetic Mapping Techniques

- Bisulfite Sequencing: The gold standard for detecting 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) at single-base resolution. Treatment with bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing for their precise mapping [4] [1].

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): This method identifies genomic regions bound by specific proteins or associated with specific histone modifications. Antibodies are used to pull down (immunoprecipitate) DNA fragments bound to a target protein (e.g., a transcription factor) or a specific histone mark (e.g., H3K27ac). The co-precipitated DNA is then sequenced to map the binding sites or modification patterns genome-wide [1].

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq): This technique probes chromatin accessibility by using a hyperactive transposase enzyme to insert sequencing adapters into open, nucleosome-free regions of the genome. It provides a map of the regulatory landscape, revealing active promoters and enhancers [1].

Epitranscriptomic Mapping Techniques

- Antibody-Based Enrichment Methods: Techniques such as MeRIP-seq (m⁶A) or miCLIP use modification-specific antibodies to immunoprecipitate modified RNA fragments. While powerful for transcriptome-wide mapping, they typically offer limited resolution (100-200 nucleotides) [2].

- Chemical Derivatization and Sequencing: For certain modifications like pseudouridine (Ψ), chemical treatments can be used to introduce mutations or adducts at the modification site during reverse transcription, allowing for its precise mapping [2].

- Direct RNA Sequencing with Nanopores: A transformative technology that allows for the direct sequencing of native RNA molecules without prior conversion to cDNA. As an RNA molecule passes through a protein nanopore, the resulting perturbations in an ionic current are sensitive to the RNA's sequence and its chemical modifications. Advanced computational analyses, including machine learning, can then be used to identify specific modifications at single-molecule resolution [2] [6]. This method is particularly promising for discovering novel modifications and for integrated analysis of multiple marks on the same RNA molecule [2].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Modification Analysis

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-m⁶A, Anti-5mC, Anti-H3K27ac | Immunoprecipitation of modified nucleic acids or histones for sequencing (MeRIP, ChIP). |

| Enzymatic Kits | Bisulfite Conversion Kit, TET enzyme kits | Convert 5mC for detection (bisulfite) or oxidize 5mC to 5hmC for subsequent analysis. |

| Direct Sequencing Platforms | Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Direct detection of RNA/DNA modifications on native molecules without chemical conversion. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Liquid Chromatography-MS | Quantitative, global profiling of modifications (e.g., histone PTMs, nucleosides) without locus-specific information. |

Functional Roles in Physiology and Disease

The dynamic nature of epigenetic and epitranscriptomic marks makes them essential for normal cellular processes, and their dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous diseases.

Role in the Central Nervous System and Neurodegeneration

The brain exhibits a particularly rich and tissue-specific epitranscriptome and epigenome. Modifications such as m⁶A are highly abundant and dynamically regulated during brain development, learning, and memory [3]. Dysregulation of these processes is strongly linked to neurodegenerative diseases:

- Alzheimer's Disease (AD): Research shows a rewiring of m⁶A methylation on promoter-antisense RNAs (paRNAs) in AD brains. One such paRNA, MAPT-paRNA, becomes more active and acts as a master regulator, influencing hundreds of neuronal genes across different chromosomes, linking epitranscriptomic changes directly to AD pathology [5]. Aberrant expression of writers (METTL3) and erasers (FTO) has also been documented in AD models [3].

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): The m¹A modification can directly promote the cytoplasmic mislocalization and aggregation of TDP-43, a key pathogenic protein in ALS [3].

- Parkinson's Disease (PD): Studies in PD models show distinct up- and down-regulation of various m⁶A regulatory proteins (e.g., ALKBH5, YTHDF1) in brain regions like the substantia nigra, indicating a role in disease mechanisms [3].

Role in Cancer

Epigenetic and epitranscriptomic dysregulation is a cardinal feature of cancer, contributing to uncontrolled proliferation, metastasis, and therapy resistance [1].

- Oncogenic Signaling: Widespread DNA hypomethylation can activate oncogenes, while hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters (e.g., BRCA1) silences them. Mutations in epigenetic enzymes like DNMT3A, TET2, and EZH2 are common driver events in hematological and solid cancers [1].

- Therapeutic Targets: The reversible nature of these modifications makes their regulatory enzymes attractive drug targets. Inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases (e.g., azacitidine) and histone deacetylases (e.g., vorinostat) are already approved for clinical use in certain cancers. Research into inhibitors of epitranscriptomic writers (e.g., METTL3) and readers is a rapidly advancing area of drug development [1].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Purpose: To transcriptome-wide map m⁶A modifications at a resolution of ~100-200 nucleotides.

- RNA Isolation and Fragmentation: Isolate high-quality total RNA from cells or tissue. Use divalent cations (e.g., Zn²⁺) or heat to fragment RNA into pieces of ~100 nucleotides.

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): Incubate the fragmented RNA with an anti-m⁶A antibody conjugated to magnetic beads. A control "Input" sample is set aside without IP.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound RNA. Elute the m⁶A-enriched RNA from the antibody-bead complex.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Convert both the IP and Input RNA samples into sequencing libraries. This typically involves reverse transcription to cDNA, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequence the libraries and align the reads to the reference genome. Peaks of enrichment in the IP sample compared to the Input sample are identified as m⁶A modification sites.

Purpose: To screen thousands of non-coding genetic variants (e.g., from genome-wide association studies) to identify those that functionally alter gene regulation.

- Library Design: Synthesize an oligonucleotide pool containing thousands of different genomic regulatory sequences (e.g., enhancers), each harboring a specific variant. Each sequence is coupled to a unique DNA barcode.

- Cloning and Delivery: Clone this library into a plasmid vector upstream of a minimal promoter and a reporter gene. Transfect the plasmid library into a relevant cell type (e.g., lung cells for lung cancer-associated variants).

- RNA Harvest and Sequencing: Harvest the cellular RNA and sequence the barcode regions. The abundance of each barcode in the RNA pool reflects the transcriptional activity driven by its associated regulatory sequence.

- Analysis: Compare the expression levels of the reference and variant sequences. Variants that cause a significant increase or decrease in barcode abundance are classified as functional regulatory variants.

The fields of epigenetics and epitranscriptomics have matured from cataloging modifications to understanding their profound functional significance in health and disease. The current landscape is defined by several key frontiers that will drive the discovery of novel modifications and their biological roles.

The development of novel sequencing technologies, particularly direct RNA and DNA sequencing via nanopores, is a major catalyst [2] [6]. This platform allows for the detection of multiple modifications simultaneously on a single molecule, without the biases introduced by chemical conversion or antibody enrichment. It is perfectly suited for exploratory discovery of the many among the 300+ known RNA modifications that remain uncharacterized in mRNA, as well as for probing non-canonical epigenetic marks [2].

The exploration of environmental RNA (eRNA) and the application of epitranscriptomics to diverse biological contexts, such as plant stress responses, will likely reveal new modification types and functions [2] [7]. Furthermore, the push for single-cell resolution mapping promises to uncover the cell-to-cell heterogeneity of epigenetic and epitranscriptomic states, which is critical for understanding complex tissues like the brain and the dynamics of tumor evolution [1].

Finally, the lessons learned from the basic biology of these modifications are being rapidly translated into clinical applications. This includes the design of modified therapeutic RNAs (e.g., mRNA vaccines with pseudouridine to evade immune sensors) and the development of small-molecule inhibitors against writers, readers, and erasers for cancer and other diseases [2] [8] [1]. As our tools and understanding continue to deepen, the systematic discovery and functional characterization of novel DNA and RNA modifications will undoubtedly redefine our understanding of gene regulation and open new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The ongoing evolutionary battle between bacteriophages (phages) and their bacterial hosts represents one of the most dynamic frontiers in molecular biology. For billions of years, phages and bacteria have co-evolved in a complex arms race, with bacteria developing diverse defense systems and phages countering with sophisticated evasion strategies [9]. A groundbreaking discovery has recently emerged from this ancient conflict: researchers from the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) have identified a novel type of phage DNA modification involving the attachment of arabinose sugars to cytosine bases [9]. This discovery, published in Cell Host & Microbe, reveals an unprecedented biological mechanism where phages modify their DNA with up to three arabinose sugars to evade bacterial defense systems [10].

This finding represents a significant advancement in the field of DNA and RNA modifications, illustrating how phage genomes employ unique chemical strategies to protect their genetic material from host detection. The arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine modifications not only provide new insights into phage biology but also offer promising avenues for developing novel therapeutic approaches against antibiotic-resistant pathogens, including Acinetobacter baumannii, classified by the World Health Organization as a critical priority pathogen [9]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the discovery, mechanistic insights, experimental methodologies, and potential applications of these novel DNA modifications.

Technical Breakdown of Arabinosyl-Hydroxy-Cytosine Modifications

Chemical Structure and Variants

The newly discovered modifications involve the enzymatic addition of arabinose sugars to cytosine bases in phage DNA through a unique chemical linkage. Researchers have identified three distinct variants of this modification, differing in the number of attached arabinose units:

- 5-arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine (5ara-hC): Single arabinose sugar attached to hydroxy-cytosine

- 5-arabinosyl-arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine (5ara-ara-hC): Double arabinosylation with two arabinose units

- 5-arabinosyl-arabinosyl-arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine (5ara-ara-ara-hC): Triple arabinosylation with three arabinose units [10]

These modifications are distinct from previously characterized DNA glycosylation patterns, particularly the well-studied 5-glucosyl-hydroxymethyl-cytosine (5ghmC) found in E. coli phage T4. The arabinose-based modifications represent a novel class of DNA hypermodifications that provide phages with unique advantages in evading bacterial immune systems [10].

Comparative Genomic Distribution

The research team identified these arabinose modifications across multiple phage families, demonstrating their widespread nature:

Table: Distribution of Arabinosyl-Hydroxy-Cytosine Modifications Across Phage Families

| Phage Name | Host Bacterium | Modification Type | Protection Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC53 | Serratia sp. ATCC 39006 | Single arabinosylation (5ara-hC) | Base level protection |

| 92A1 | Serratia strain 95 | Single arabinosylation (5ara-hC) | Base level protection |

| RB69 | Escherichia coli | Double arabinosylation (5ara-ara-hC) | Enhanced protection |

| Bas46 | Escherichia coli | Double arabinosylation (5ara-ara-hC) | Enhanced protection |

| Bas47 | Escherichia coli | Double arabinosylation (5ara-ara-hC) | Enhanced protection |

| Maestro | Acinetobacter baumannii | Triple arabinosylation (5ara-ara-ara-hC) | Maximum protection [10] |

Mechanistic Insights: Phage-Encoded Enzymatic Machinery

The arabinose modifications are synthesized by phage-encoded arabinose-5ara-hC transferases (Aat enzymes). These enzymes facilitate the stepwise addition of arabinose units to hydroxy-cytosine bases in phage DNA, with the number of attached arabinose units directly correlating with the level of protection against bacterial defense systems [10]. The modifications occur through both pre- and post-replication modification steps, similar to mechanisms observed in other modified phage genomes but with distinct biochemical pathways specific to arabinose attachment.

Experimental Characterization and Validation

Analytical Platform for Novel DNA Modification Detection

The research team at SMART AMR developed a highly sensitive analytical platform capable of detecting and identifying novel phage DNA modifications. This platform combines advanced analytical techniques with bioinformatic tools to characterize previously unrecognized modification systems [9]. Key components of their methodology included:

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: High-resolution mass spectrometry was employed to identify the unique mass signatures of arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine modifications and distinguish between single, double, and triple arabinosylated forms.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: The team utilized NMR to characterize the chemical structure of the modified nucleotides, confirming the arabinose-cytosine linkage and the configuration of multiple arabinose units [10].

Genomic Sequencing and Bioinformatics: Comparative genomic analysis of modified and unmodified phage DNA helped identify the genetic determinants responsible for the modification machinery.

Functional Assays for Evasion Capability Assessment

To evaluate the functional significance of these DNA modifications, researchers conducted a series of experiments testing phage susceptibility to various bacterial defense systems:

Table: Protection Profile of Arabinosyl-Hydroxy-Cytosine Modifications Against Bacterial Defense Systems

| Bacterial Defense System | Protection Afforded by Single Arabinosylation | Protection Afforded by Double Arabinosylation | Protection Afforded by Triple Arabinosylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I CRISPR-Cas | Partial | Significant | Complete |

| Type II Restriction-Modification Systems | Partial | Significant | Complete |

| Type III CRISPR-Cas (RNA-targeting) | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable |

| Type IV Restriction-Modification | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable |

| Type VI CRISPR-Cas (RNA-targeting) | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable |

| DNA Glycosylases Targeting 5ghmC | Evaded | Evaded | Evaded [10] |

The experimental data demonstrated that phages with double arabinose modifications showed significantly better protection against DNA-targeting defenses compared to those with single modifications. Triple arabinosylation provided the highest level of protection, enabling near-complete evasion of certain bacterial immune mechanisms [10].

Genetic Engineering Approaches

The research team established methods for genetically engineering these phages with specific DNA modifications, facilitating their future development as therapeutics. By manipulating the genes encoding Aat enzymes, researchers could control the extent of arabinosylation, creating phages with tailored evasion capabilities against specific bacterial defense mechanisms [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

The study and application of arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine modifications require specialized research tools and reagents. The following table outlines essential materials for working with these novel DNA modifications:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Arabinosyl-Hydroxy-Cytosine Modification Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Enzymes | AbaSI (NEB #R0665), Benzonase Nuclease, DNase I | Detection and characterization of modified nucleases; DNA digestion for analysis |

| Chromatography Reagents | Acetonitrile, AMPure XP Reagent | Separation and purification of modified nucleotides for mass spectrometry |

| Modified Nucleotide Standards | 5-arabinofuranosyl-hydroxy-dC, 5-arabinofuranosyl-arabinofuranosyl-hydroxy-dC | NMR reference standards for structural identification |

| Arabinose Compounds | D-Arabinose | Induction studies and control of arabinose-dependent systems |

| Cloning & Expression Systems | pBAD expression vectors, Arabinose-inducible artificial transcription factors | Controlled expression of modification enzymes; engineering of arabinose-responsive systems [10] [11] |

| Specialized Stains & Detection | Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), Ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) | Selective precipitation and analysis of modified DNA; metal chelation for enzyme studies |

Pathway and Mechanism Visualization

The complex interactions between phage modification systems and bacterial defense mechanisms can be visualized through the following pathway diagram:

Diagram Title: Phage-Bacterial Arms Race via DNA Arabinosylation

The diagram illustrates the sequential process where phage infection triggers bacterial defense systems, leading to the activation of phage-encoded arabinose transferases that modify viral DNA. The arabinosylated DNA evades detection by DNA-targeting systems, creating selective pressure that drives the continuous coevolution of phage and bacterial mechanisms.

Research Implications and Future Directions

Therapeutic Applications Against Antimicrobial Resistance

The discovery of arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine modifications has significant implications for addressing the global antimicrobial resistance crisis. Phage therapy represents a promising alternative to conventional antibiotics, particularly for infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens. The enhanced understanding of how phages naturally evade bacterial defenses enables researchers to engineer more effective phage therapeutics [9]. Specifically, this knowledge could be leveraged to develop targeted phage treatments for critical antibiotic-resistant pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii, which causes life-threatening infections including pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis [9].

Fundamental Revisions to Phage Biology

This research has revealed that natural DNA modifications in phages occur at a much higher rate than previously predicted, suggesting a vast potential for discovering other novel phage DNA modification systems [9]. The findings revise fundamental understanding of phage biology and open new avenues for exploring the extensive diversity of epigenetic modifications in viral genomes. The discovery that phages can hypermodify their DNA with multiple sugar units demonstrates a previously underappreciated level of biochemical complexity in phage evasion strategies.

Biotechnology and Synthetic Biology Applications

Beyond therapeutic applications, the mechanistic insights from arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine modifications offer valuable tools for biotechnology and synthetic biology. The arabinose-inducible expression systems, long used in molecular biology [12] [11] [13], can be further refined using principles derived from phage modification systems. Additionally, the unique properties of arabinosylated DNA may inspire novel biomaterials or molecular engineering approaches that leverage these natural modification pathways for technological applications.

The discovery of arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytosine modifications in phage DNA represents a significant milestone in the field of DNA modifications research. This breakthrough not only enhances our understanding of the complex molecular arms race between phages and bacteria but also provides valuable insights that could lead to novel therapeutic strategies against antibiotic-resistant pathogens. The sophisticated modification system, with its gradations of protection corresponding to the number of arabinose units, demonstrates the remarkable evolutionary innovation emerging from phage-bacterial interactions.

As research in this field advances, the continued exploration of novel DNA and RNA modifications will undoubtedly reveal additional layers of complexity in biological systems. The interdisciplinary approach combining analytics, informatics, genomics, and molecular biology that enabled this discovery serves as a model for future investigations into epigenetic modifications and their functional consequences across diverse biological contexts.

The epitranscriptome, comprising post-transcriptional chemical modifications to RNA, represents a crucial regulatory layer in gene expression. The "writer-eraser-reader" paradigm governs the installation, interpretation, and removal of these modifications, enabling dynamic control of RNA metabolism without altering the underlying nucleotide sequence. This framework plays fundamental roles in cellular homeostasis, and its dysregulation is increasingly implicated in disease pathologies, particularly cancer and drug resistance. This technical guide explores the core machinery of major RNA modifications including N6-methyladenosine (m6A), 5-methylcytosine (m5C), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), 7-methylguanosine (m7G), pseudouridine (Ψ), and adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) editing, with emphasis on experimental approaches and research tools driving discovery in this rapidly evolving field.

RNA modifications represent a critical regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, forming what is now known as the "epitranscriptome." These chemical alterations to RNA nucleotides constitute a sophisticated regulatory system that influences RNA fate, function, and metabolism. The writer-eraser-reader paradigm provides the fundamental framework for understanding how these modifications exert their functional effects:

- Writers: Enzymes that catalyze the addition of specific chemical modifications to RNA molecules. These include methyltransferases that add methyl groups to various nucleotide positions.

- Erasers: Enzymes that remove modifications, allowing for dynamic regulation and reversibility of the modification state.

- Readers: Proteins that recognize and bind to specific modifications, translating the chemical mark into functional consequences by recruiting effector complexes that influence RNA splicing, stability, localization, translation, and degradation.

This coordinated system enables precise, reversible control of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, allowing cells to rapidly adapt to environmental changes and developmental cues. The combinatorial potential of multiple modifications across individual RNA molecules creates a complex regulatory landscape that researchers are only beginning to decipher.

Major RNA Modifications and Their Regulatory Machinery

Core Modification Types and Functions

Table 1: Major RNA Modifications and Their Primary Functions

| Modification | Prevalence | Primary Functions | Key Regulatory Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| m6A (N6-methyladenosine) | Most abundant mRNA modification [14] | mRNA stability, splicing, translation, degradation [15] | Stem cell differentiation, neurogenesis, cancer progression [16] |

| m5C (5-methylcytosine) | mRNA, tRNA, rRNA [17] | RNA stability, nuclear export, translation [14] | Stress response, protein synthesis [16] |

| m1A (N1-methyladenosine) | mRNA, tRNA, rRNA | Translation regulation, RNA structure [14] | Cell proliferation, migration in cancer [14] |

| m7G (7-methylguanosine) | mRNA 5' cap, internal positions | RNA cap structure, protection from degradation [17] | Translation initiation, RNA processing [17] |

| Ψ (Pseudouridine) | mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, snRNA | RNA stability, structure, translation [14] | Detection biomarker in bodily fluids [14] |

| A-to-I Editing | mRNA, primarily coding regions | Codon alteration, splice regulation [18] | Neurodevelopment, cancer, therapeutic applications [18] |

Writer, Eraser, and Reader Components

Table 2: Regulatory Machinery for Major RNA Modifications

| Modification | Writers | Erasers | Readers |

|---|---|---|---|

| m6A | METTL3/METTL14 complex, METTL16, WTAP [19] [17] | FTO, ALKBH5 [19] [17] | YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2 [19] [17] |

| m5C | NSUN2, NSUN6, DNMT2, TRDMT1 [17] | TET enzymes [17] | ALYREF [17] |

| m1A | TRMT10C, TRMT61A, TRMT6 [14] | Not well characterized | YTHDF1-3 [14] |

| m7G | METTL1/WDR4 complex, RNMT [17] | Not identified | Not identified |

| Ψ | Pseudouridine synthases (PUSs), DKC1 [14] | None identified (irreversible) [14] | None identified [14] |

| A-to-I Editing | ADAR1, ADAR2 [18] | None (technically a base change) | Cellular machinery reads inosine as guanosine [18] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying RNA Modifications

Detection and Mapping Technologies

Advancements in detection technologies have been crucial for epitranscriptomics research. Current methods can be broadly categorized into antibody-based enrichment approaches and direct RNA sequencing methods.

Nanopore Direct RNA Sequencing represents a transformative technology that enables detection of RNA modifications in individual RNA molecules without prior chemical conversion or enrichment. The CHEUI (CH3 Estimation Using Ionic current) computational tool exemplifies recent advances, employing a two-stage neural network to predict m6A and m5C at single-molecule resolution from the same sample [16]. This method processes observed and expected nanopore signals to achieve high single-molecule, transcript-site, and stoichiometry accuracies.

Antibody-Based Enrichment Methods including MeRIP-seq and miCLIP remain widely used but require specific antibodies for each modification and typically cannot detect multiple modifications simultaneously or reveal co-occurrence on individual molecules.

EpiPlex Platform offers an emerging solution for multiplexed detection, using proximity barcoding to translate RNA modifications into unique barcodes read by next-generation sequencing. This approach can detect multiple modifications (including m6A and inosine) in a single reaction with minimal input material, making it suitable for biopsy samples [20].

CHEUI Workflow for m6A and m5C Detection

The CHEUI methodology provides a robust framework for detecting m6A and m5C modifications at single-molecule resolution:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Isolate RNA from experimental and control conditions

- Perform nanopore direct RNA sequencing without PCR amplification

- Base-call raw signals to generate sequencing reads aligned to reference transcriptome

Signal Preprocessing:

- Extract observed nanopore signals for 9-mer windows centered on each adenosine (for m6A) or cytosine (for m6C)

- Calculate expected unmodified signal values for each 9-mer context

- Compute distance metrics between observed and expected signals

- Generate feature vectors combining raw signals and distance metrics

Model Application:

- Process feature vectors through CHEUI-solo Model 1 CNN to predict modification status for individual reads

- Aggregate individual read predictions using CHEUI-solo Model 2 to estimate modification probability at each transcriptomic site

- For comparative analyses, use CHEUI-diff to statistically test differential modification rates between conditions

Validation:

- Validate predictions using synthetic RNA standards with known modification status

- Employ orthogonal methods (antibody-based enrichment, mass spectrometry) for confirmation

- Utilize cell lines with writer/eraser knockouts for benchmarking

This approach achieves approximately 80% accuracy for m6A and 75% for m5C detection in individual reads, with performance improvements possible through double-cutoff strategies (0.7/0.3 probability thresholds) that increase AUC while retaining 73% of reads [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for RNA Modification Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Platforms | EpiPlex (Alida Biosciences) | Multiplex detection of m6A, inosine, Ψ in single reaction [20] |

| Computational Tools | CHEUI, m6Anet, Nanom6A, Epinano | Modification detection from nanopore DRS data [16] |

| Oligonucleotide Design Platforms | OPERA (Korro Bio), RESTORE+ (AIRNA) | Design of ADAR-recruiting oligonucleotides for RNA editing [20] |

| AI/ML Platforms | BigRNA, DeepADAR (Deep Genomics) | Predictive modeling for oligonucleotide design and target identification [20] |

| Reference Materials | In vitro transcribed RNA standards | Validation and benchmarking of detection methods [16] |

| Cell Line Models | Writer/eraser knockout lines (e.g., METTL3 KO, FTO KO) | Functional studies and method validation [19] |

Research Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Role in Disease Mechanisms

RNA modifications play critical roles in disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer:

Drug Resistance in Cancer: Aberrant RNA modifications contribute significantly to chemoresistance across cancer types. METTL3 upregulation in breast cancer enhances stability of HYOU1 mRNA through m6A modification, conferring resistance to cisplatin [19]. ALKBH5 modulates chemotherapy resistance in triple-negative breast cancer by regulating FOXO1 mRNA stability [19]. In gynecological cancers, m6A readers like YTHDF1 promote ovarian cancer development by enhancing EIF3C translation [14].

Cancer Biomarker Development: Multi-modification signatures show promise for cancer prognosis. A methylation-related risk score (MARS) incorporating m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G regulators effectively stratifies clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients and predicts immunotherapy response [17]. Pseudouridine shows potential as a detection biomarker for ovarian cancer due to elevated levels in patient plasma [14].

Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

Small Molecule Inhibitors: Development of inhibitors targeting writer and eraser enzymes represents a promising therapeutic approach. METTL3 and FTO inhibitors show potential for sensitizing cancer cells to conventional chemotherapy [21]. Combination therapies pairing RNA modification inhibitors with standard chemotherapeutics demonstrate synergistic effects in preclinical models [21].

RNA Editing Therapeutics: ADAR-based RNA editing platforms (e.g., OPERA from Korro Bio, RESTORE+ from AIRNA) enable precise A-to-I editing to correct disease-causing mutations [20]. KRRO-110, an RNA editing therapeutic for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, exemplifies clinical translation with orphan drug designation and ongoing clinical trials [20].

Antisense Oligonucleotides: ASOs can manipulate RNA modification pathways or function through steric blockade mechanisms. Splice-switching ASOs represent an established approach, with approved drugs like eteplirsen (exon skipping) and nusinersen (exon inclusion) demonstrating clinical utility [22].

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite rapid progress, several challenges remain in epitranscriptomics research and therapeutic development:

Technical Limitations: Current methods struggle with comprehensive detection of multiple modifications on individual molecules, though platforms like EpiPlex and CHEUI are addressing this gap. The requirement for specialized computational expertise and validation standards continues to hinder widespread adoption.

Therapeutic Delivery: Efficient, tissue-specific delivery of RNA-targeting therapeutics remains a primary obstacle. While lipid nanoparticles and GalNAc conjugates have improved hepatic delivery, targeting other tissues, particularly the central nervous system, requires further innovation [18].

Resistance Mechanisms: As with conventional targeted therapies, resistance to epitranscriptomic therapeutics may emerge through compensatory mechanisms and adaptive cellular responses. Combination approaches targeting multiple nodes in modification networks may help overcome this challenge [21].

Functional Integration: Understanding how multiple modifications interact combinatorially to regulate RNA function represents a frontier in epitranscriptomics. The development of technologies that simultaneously map different modifications on individual transcripts will be crucial for deciphering this complex regulatory code.

The writer-eraser-reader paradigm continues to expand as new modifications, regulatory proteins, and functional relationships are discovered. Integration with other epigenetic regulatory layers and single-cell technologies will further illuminate the multifaceted roles of RNA modifications in health and disease, opening new avenues for basic research and therapeutic intervention.

The discovery of numerous chemical modifications on RNA molecules has established the field of epitranscriptomics as a critical frontier in molecular biology, parallel to the well-established study of DNA modifications. These dynamic, reversible RNA changes represent a fundamental layer of post-transcriptional gene regulation that influences RNA stability, splicing, translation, and degradation [23]. To date, over 170 distinct chemical modifications have been identified across various RNA species, including messenger RNA (mRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and non-coding RNAs [3] [24]. This expanding universe of RNA modifications functions through a sophisticated enzymatic machinery of "writer," "eraser," and "reader" proteins that install, remove, and interpret these chemical marks, respectively [3] [23]. The dysregulation of this precise system is now implicated across the pathological spectrum, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic diseases, positioning RNA modifications as both critical disease mediators and promising therapeutic targets [23] [24]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on novel RNA modifications, their mechanistic roles in human disease, and the advanced methodologies propelling this rapidly evolving field toward clinical translation.

Fundamental Mechanisms of RNA Modifications

The Writer-Eraser-Reader System

The dynamic nature of RNA modifications is governed by a highly regulated protein system that ensures precise spatiotemporal control of epitranscriptomic marks:

Writer Proteins: Enzymes responsible for adding chemical modifications to RNA substrates. The m^6A methyltransferase complex represents a canonical writer system, consisting of a core heterodimer of METTL3 (catalytic subunit) and METTL14 (structural scaffold), along with regulatory proteins such as WTAP, which facilitates complex localization and RNA targeting [3] [23]. Additional writers include METTL16 for specific nuclear mRNA targets, and KIAA1429 (VIRMA), which recruits the methyltransferase complex to specific RNA regions [3].

Eraser Proteins: Demethylases that remove RNA modifications, enabling dynamic regulation. The two primary m^6A erasers are FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated protein) and ALKBH5 (AlkB homolog 5), both belonging to the Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily but exhibiting distinct substrate preferences and tissue distributions [3] [23]. While both reverse m^6A, FTO employs a stepwise oxidative demethylation process (m^6A→hm^6A→f^6A→A), whereas ALKBH5 catalyzes direct conversion to adenosine [3].

Reader Proteins: Recognition factors that bind specifically to modified RNA and transduce the chemical signal into functional consequences. The YTH domain-containing proteins (YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2) represent the best-characterized m^6A readers, with YTHDF1 promoting translation, YTHDF2 facilitating RNA degradation, and YTHDC1 regulating splicing and nuclear export [3] [23].

Major RNA Modification Types

Table 1: Key RNA Modifications and Their Functional Roles

| Modification | Chemical Nature | RNA Targets | Primary Functions | Associated Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N6-methyladenosine (m^6A) | Methylation of adenosine at N6 position | mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, lncRNA | Splicing, export, stability, translation | METTL3/14, FTO, ALKBH5, YTHDF1-3 |

| 5-Methylcytosine (m^5C) | Methylation of cytosine at C5 position | mRNA, tRNA, rRNA | Nuclear export, translation, stability | NSUN2, DNMT2, ALYREF |

| N1-methyladenosine (m^1A) | Methylation of adenosine at N1 position | tRNA, rRNA | tRNA folding, translation fidelity | TRMT6/61A, ALKBH3 |

| N7-methylguanosine (m^7G) | Methylation of guanosine at N7 position | mRNA 5' cap, tRNA, miRNA | Protection from decay, translation initiation | RNMT, BCDIN3D |

| Pseudouridine (Ψ) | Isomerization of uridine | rRNA, tRNA, snRNA | RNA folding, stability, translation | Dyskerin, PUS1-10 |

The most abundant internal mRNA modification, m^6A, occurs predominantly within the RRACH consensus motif (R = G/A; H = A/C/U) and is enriched near stop codons and in 3' untranslated regions (3'UTRs) [3] [23]. This modification profoundly influences mRNA metabolism through recruitment of reader proteins that dictate subsequent processing events. The 5' cap modification m^7G represents another critical regulatory node, protecting mRNAs from exonuclease degradation and facilitating translation initiation through recognition by eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) [24]. Meanwhile, tRNA modifications such as m^1A and m^5C play essential roles in maintaining structural integrity, optimizing codon-anticodon interactions, and regulating translation fidelity [23].

RNA Modifications in Cancer Pathogenesis

Oncogenic Reprogramming of the Epitranscriptome

Cancer cells exhibit widespread dysregulation of RNA modification patterns that drive malignant transformation and tumor progression. The m^6A modification serves as a pivotal regulator in oncogenesis, with its writers, erasers, and readers frequently displaying altered expression across cancer types:

METTL3 demonstrates context-dependent roles, functioning as both an oncogene and tumor suppressor in different malignancies. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), METTL3 overexpression promotes translation of oncogenic transcripts including MYC and BCL2, while in pancreatic cancer it exhibits tumor-suppressive properties [25] [23].

FTO is frequently overexpressed in AML and glioblastoma, where it removes m^6A marks from oncogenic transcripts such as MYC and CEBBPA, enhancing their stability and promoting proliferation [25] [23].

YTHDF1 reader function is hijacked in hepatocellular carcinoma, where it recognizes m^6A-modified transcripts encoding components of the WNT/β-catenin pathway, driving uncontrolled proliferation [25].

The National Cancer Institute has established the RNA Modifications Driving Oncogenesis (RNAMoDO) Program to systematically investigate how dysregulated RNA modifications reprogram translation in cancer cells [26]. Funded projects are examining diverse modifications, including 5-formylcytosine in AML (City of Hope), the relationship between methionine metabolism and rRNA/tRNA modifications (Scripps Research Institute), tRNA modification reprogramming in melanoma metastasis (University of Massachusetts), and dihydrouridine modifications in tRNA affecting mRNA stability in renal cell carcinoma (UT Southwestern) [26].

RNA Modifications in Cancer Metabolism and Metastasis

Cancer-associated RNA modifications extend beyond m^6A to encompass a broad epitranscriptomic network that rewires cellular metabolism and facilitates metastatic progression:

m^5C modifications, installed by writers such as NSUN2 and read by ALYREF, promote the nuclear export of oncogenic transcripts and are dysregulated in breast and gastrointestinal cancers [25] [24].

tRNA modifications including m^1A, m^5C, and queuosine regulate translation of specific codon-biased mRNAs involved in cell proliferation and stress response, creating a translation program that supports tumor growth [26].

m^7G cap methylation by RNMT is elevated in breast cancer, enhancing the translation of cell cycle regulators such as Cyclin D1 and driving uncontrolled proliferation [24].

The dynamic nature of these modifications allows cancer cells to rapidly adapt to therapeutic challenges and microenvironmental stresses, including hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and oxidative stress [25]. Furthermore, epitranscriptomic changes in non-coding RNAs, particularly miRNAs and lncRNAs, create extensive regulatory networks that influence essentially all hallmarks of cancer [24].

RNA Modifications in Neurological Disorders

Neurodegenerative Diseases and RNA Modification Dysregulation

The central nervous system exhibits particularly high abundance and complexity of RNA modifications, which play critical roles in neuronal development, function, and survival [3]. Dysregulation of this sophisticated epitranscriptomic landscape is increasingly implicated in neurodegenerative pathogenesis:

Alzheimer's Disease (AD): Comprehensive profiling of m^6A patterns in postmortem human brain tissue has revealed substantial epitranscriptomic rewiring in AD [5]. A key finding identifies altered m^6A methylation on promoter-antisense RNAs (paRNAs), particularly MAPT-paRNA, which originates from the tau gene locus but functions as a master regulator influencing approximately 200 genes across multiple chromosomes through 3D genome organization [5]. This mechanism links epitranscriptomic changes to the widespread transcriptional dysregulation observed in AD. Additionally, METTL3 is downregulated in the hippocampus of AD patients, while FTO demonstrates increased expression, suggesting a net loss of m^6A methylation that contributes to pathological tau accumulation and neuronal dysfunction [3].

Parkinson's Disease (PD): Distinct alterations in m^6A regulatory components occur in brain regions affected by PD. In the substantia nigra of PD models, proteins including ALKBH5 and IGF2BP2 are upregulated, while YTHDF1 and FMR1 are downregulated. In the striatum, different patterns emerge with FMR1 upregulation and METTL3 downregulation, indicating region-specific epitranscriptomic disturbances [3].

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): The ALS-associated protein TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) directly binds m^1A-modified RNAs, which stimulates its cytoplasmic mislocalization and aggregation—a hallmark of ALS pathology [3]. This finding directly connects RNA modifications to protein misfolding events in neurodegeneration.

Mechanistic Insights from Model Systems

Studies in model organisms have provided crucial insights into how RNA modifications influence neuronal integrity. In transgenic C. elegans models expressing human tau and TDP-43, loss of the m^5C reader protein ALYREF ameliorates tau- and TDP-43-induced locomotor deficits and reduces pathological protein accumulation [3]. Similarly, m^6A deficiency exacerbates tau toxicity, while its restoration protects against neurodegeneration, suggesting potential therapeutic avenues [3]. The emerging paradigm indicates that RNA modifications regulate key aspects of neuronal biology, including axon guidance, synaptic plasticity, and stress response, with their dysruption creating vulnerability to degenerative processes.

Technological Advances in Epitranscriptomics

Novel Profiling Methodologies

Recent methodological innovations have dramatically accelerated the mapping and quantification of RNA modifications:

LIME-seq (Low-Input Multiple Methylation Sequencing): This novel approach enables simultaneous detection of multiple RNA modifications at nucleotide resolution from minimal input material, including clinically relevant samples like blood plasma [27]. A key innovation in LIME-seq is the use of HIV reverse transcriptase to generate cDNA from cell-free RNA, coupled with an RNA-cDNA ligation strategy that captures short RNA species (e.g., tRNA) typically lost in conventional RNA-seq protocols. When applied to plasma samples from colorectal cancer patients and healthy controls, LIME-seq revealed significant tRNA methylation changes between groups, demonstrating utility for non-invasive cancer detection [27].

Automated tRNA Modification Profiling: Researchers at the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) have developed a robotic platform that automates tRNA modification analysis across thousands of biological samples [28]. This system integrates robotic liquid handlers with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to generate high-resolution modification maps without hazardous chemical handling. In one application, the platform analyzed tRNA from over 5,700 strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, generating 200,000 data points that revealed new tRNA-modifying enzymes and regulatory networks [28].

Table 2: Advanced Methodologies for RNA Modification Analysis

| Method | Principle | Applications | Throughput | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIME-seq | Reverse transcription with specialized enzymes + ligation | Cell-free RNA modification profiling | High | Captures short RNAs; multiple modifications simultaneously |

| Automated LC-MS/MS | Robotic sample prep + mass spectrometry | tRNA modification screening | Very High (1000s samples) | Fully automated; quantitative; discovers new enzymes |

| Antibody-based Enrichment | Immunoprecipitation with modification-specific antibodies | m^6A mapping in tissues | Medium | Tissue-specific epitranscriptome mapping |

| Prime Editing | Precise genome editing to install suppressor tRNAs | Therapeutic correction of nonsense mutations | N/A | Disease-agnostic; permanent correction |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for RNA Modification Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modification-Specific Antibodies | Anti-m^6A, Anti-m^5C, Anti-m^1A | Enrichment and mapping of specific modifications | MeRIP-seq, m^6A-LAIC-seq [5] |

| Enzymatic Writers/Erasers | Recombinant METTL3/14, FTO, ALKBH5 | In vitro modification studies; functional validation | Methyltransferase/demethylase assays [3] |

| Reader Domain Proteins | YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2 recombinant proteins | Identification of modification sites; functional studies | RNA-protein interaction assays [23] |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Isotope-labeled nucleosides | Absolute quantification of modifications | LC-MS/MS calibration [28] |

| Specialized Reverse Transcriptases | HIV reverse transcriptase | cDNA synthesis from modified RNA | LIME-seq [27] |

| Prime Editing Systems | PERT (Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough) | Installation of suppressor tRNAs | Correction of nonsense mutations [29] |

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

Targeting RNA Modifications in Cancer

The therapeutic potential of modulating RNA modifications is being actively explored, particularly in oncology:

Enzyme-Targeting Strategies: Small molecule inhibitors targeting RNA-modifying enzymes are under development, including FTO inhibitors that show promise in preclinical models of AML and glioblastoma [23]. Conversely, METTL3 stabilizers are being investigated for contexts where enhancing m^6A methylation may have therapeutic benefits.

mRNA Cancer Vaccines: RNA modification knowledge has been successfully applied to improve mRNA-based cancer immunotherapies. Modifications such as pseudouridine and 5-methylcytosine are incorporated into therapeutic mRNAs to reduce immunogenicity and enhance stability, as demonstrated in the COVID-19 vaccines BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 [24]. Similar approaches are now being applied to cancer vaccines in clinical trials, with encouraging preliminary results [24].

Disease-Agnostic Genetic Therapies

A groundbreaking approach called PERT (Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough of Premature Termination Codons) demonstrates the potential of disease-agnostic therapies targeting RNA-related mechanisms [29]. Rather than correcting individual mutations, PERT uses prime editing to install a suppressor tRNA gene into the genome that enables readthrough of premature stop codons, regardless of which gene contains the mutation. This single editing system has shown efficacy in cell and animal models of four different genetic diseases—Batten disease, Tay-Sachs disease, Niemann-Pick disease type C1, and Hurler syndrome—restoring protein production to therapeutic levels (6-70% of normal) without detectable off-target effects [29].

Visualizing Key Mechanisms and Workflows

The RNA Modification Regulatory System

Diagram 1: The Writer-Eraser-Reader System of RNA Modifications. Writer enzymes (blue) add chemical groups to RNA, erasers (red) remove them, and reader proteins (green) recognize the modifications to direct functional outcomes including RNA processing, stability, and translation.

LIME-seq Workflow for Modification Profiling

Diagram 2: LIME-seq Workflow for Comprehensive RNA Modification Profiling. This method enables simultaneous detection of multiple RNA modifications from minimal input material, particularly valuable for clinical samples like blood plasma.

The study of novel RNA modifications has evolved from fundamental biochemical characterization to recognition as a critical regulatory layer in human disease pathogenesis. The expanding epitranscriptomic landscape encompasses diverse chemical modifications that influence essentially all aspects of RNA metabolism, with demonstrated roles in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other pathological conditions. Key challenges remain, including understanding the context-specific functions of RNA modifications, developing more comprehensive mapping technologies, and translating mechanistic insights into targeted therapies.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: First, expanding epitranscriptome analysis to single-cell resolution will reveal cellular heterogeneity in RNA modification patterns and their contributions to disease processes. Second, integrating multi-omics approaches will elucidate how RNA modifications interface with genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic networks in disease states. Third, advancing chemical biology and screening approaches will accelerate the development of small molecule modulators targeting RNA-modifying enzymes. Finally, clinical translation will benefit from continued development of non-invasive diagnostic platforms based on detecting epitranscriptomic signatures in liquid biopsies.

The rapid progress in epitranscriptomics underscores its transformative potential for precision medicine. As research continues to decode the complex language of RNA modifications and develop innovative tools for its manipulation, this dynamic field promises to yield novel biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and treatment strategies across the spectrum of human disease.

The central dogma of molecular biology has long defined RNA as a transient intermediary between the stable genetic information stored in DNA and the functional executors of cellular processes, proteins. However, this simplified view has been fundamentally transformed by the discovery of sophisticated chemical modification systems that regulate both nucleic acids. Cells extensively modify their DNA and RNA, creating a complex layer of regulatory information that controls gene expression patterns, maintains genomic integrity, and enables rapid cellular adaptation without altering the underlying nucleotide sequence.

This article explores the biological imperative driving these modification systems, framing our discussion within the context of discovering novel DNA and RNA modifications and their research methodologies. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding these dynamic modifications is increasingly crucial as they represent a new frontier of therapeutic targets and diagnostic tools. The integrated systems of DNA and RNA modifications form a coordinated regulatory network that fine-tunes gene expression from chromosome to transcript, representing one of the most exciting areas of modern molecular biology and therapeutic development.

DNA Modifications: Stable Regulators of Genetic Potential

Fundamental Functions and Biological Roles

DNA modifications represent stable, heritable marks that regulate gene expression potential without changing the DNA sequence itself. These epigenetic marks serve critical functions in development, cellular differentiation, and maintaining genomic stability.

Transcriptional Regulation: DNA methylation primarily occurs at cytosine residues in CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC). When concentrated in promoter-associated CpG islands, this modification typically leads to transcriptional silencing or downregulation of gene expression. This silencing occurs through two primary mechanisms: by physically impeding the binding of transcription factors to DNA or by recruiting proteins that promote the formation of transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin [30].

Genomic Integrity: DNA methylation plays a crucial role in maintaining genomic stability by suppressing the activity of transposable elements and preventing chromosomal rearrangements. Additionally, methylation establishes and maintains parental genomic imprinting, where genes are expressed in a parent-of-origin-specific manner, and facilitates X-chromosome inactivation in female mammals [30].

Cellular Differentiation and Development: The DNA methylation landscape is dynamically reprogrammed during embryonic development, creating cell-type-specific methylation patterns that lock in gene expression programs necessary for cellular differentiation. This programming allows genetically identical cells to maintain distinct identities and functions [30].

Cellular Memory and Environmental Response: Epigenetic marks provide a mechanism for cells to "remember" their developmental history and past environmental exposures. DNA methylation patterns can be stable through multiple cell divisions, allowing a sustained transcriptional response to transient environmental signals [30].

Novel DNA Modifications: Beyond 5mC, other modifications like 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine, and 5-carboxylcytosine have been identified, though their functions are less characterized. These may represent intermediate states in active demethylation pathways or possess distinct regulatory functions themselves [31].

Table 1: Primary Biological Functions of DNA Modifications

| Function | Key Modifications | Molecular Mechanism | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Silencing | 5-methylcytosine (5mC) | Methylation of promoter CpG islands impedes transcription factor binding and recruits repressive complexes | Stable, heritable gene silencing; genomic imprinting |

| Genome Stability | 5mC | Suppression of transposable elements and repetitive DNA | Prevention of chromosomal rearrangements and mutations |

| Cellular Differentiation | 5mC, 5hmC | Establishment of cell-type-specific methylation patterns during development | Lineage commitment and maintenance of cellular identity |

| Environmental Response | 5mC | Dynamic methylation changes in response to external stimuli | Cellular adaptation without changes to DNA sequence |

DNA Modification Detection and Manipulation Technologies

Advanced technologies have been developed to decode the DNA methylation landscape, with significant implications for basic research and clinical applications, particularly in oncology.

Bisulfite Sequencing: Whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) is considered the gold standard for methylation analysis, providing single-base resolution maps of 5mC across the entire genome. This method treats DNA with bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, allowing for their precise identification during sequencing [30] [32]. Recent advances have combined bisulfite conversion with long-read nanopore sequencing, though read lengths have been limited to approximately 1.5 kb due to DNA fragmentation [32].

Enzyme-Based Methods: Newer approaches utilize enzymes like APOBEC to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils, significantly reducing DNA fragmentation and enabling much longer read lengths of approximately 5 kb when combined with nanopore sequencing. This advancement represents a significant improvement for analyzing methylation patterns across large genomic regions [32].

Third-Generation Sequencing: Technologies like Oxford Nanopore Technologies can detect DNA modifications natively without pre-conversion, by analyzing changes in the electrical current signatures as DNA strands pass through nanopores. This approach allows for simultaneous sequencing and methylation profiling [30].

Targeted DNA Methylation Editing: The dCas9-Tet1 system represents a breakthrough for functionally validating methylation-dependent gene regulation. This system uses a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to the catalytic domain of TET1, an enzyme that initiates DNA demethylation. When guided by specific RNAs to genomic targets, it enables precise, locus-specific demethylation to study the functional consequences of removing this epigenetic mark [32].

CRISPR-Mediated Knock-in: The LOCK method enables high-efficient insertion of long DNA fragments (1-3 kb) using donors with 3'-overhangs and microhomology-mediated end joining, facilitating the study of gene function in their native genomic and epigenetic context [32].

RNA Modifications: Dynamic Regulators of Gene Expression

The RNA Modification Landscape and Molecular Functions

RNA modifications represent a diverse array of post-transcriptional regulations that dynamically influence RNA metabolism, function, and stability. Over 170 different chemical modifications have been identified across all RNA classes, creating a complex regulatory layer known as the "epitranscriptome" [33] [23].

The Writer-Eraser-Reader System: RNA modifications are dynamically regulated through a sophisticated enzymatic machinery. "Writer" complexes install modifications, "eraser" enzymes remove them, and "reader" proteins recognize the modifications and execute functional outcomes. This system creates a reversible, tunable regulatory mechanism that allows cells to rapidly respond to changing conditions [33] [34] [23].

mRNA Metabolism Regulation: The most well-studied mRNA modification, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), influences nearly every aspect of RNA metabolism, including splicing, nuclear export, translation efficiency, and decay. Other modifications like m5C, m1A, and pseudouridine (Ψ) also contribute to fine-tuning mRNA fate [33] [34] [23].

Translation Optimization: Modifications in transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) are crucial for optimizing protein synthesis. They enhance tRNA stability, improve codon-anticodon interactions, maintain ribosomal structure, and ensure translational fidelity. For instance, m5C modifications in tRNA maintain structural stability, while m1A modifications in rRNA influence ribosome assembly [34] [23].

Immune Regulation: RNA modifications serve as critical regulators of immune cell biology, influencing development, differentiation, activation, and migration. They modulate the expression of key immune-related genes and can function as "self" markers to prevent aberrant immune activation against endogenous RNA [34].

Table 2: Major RNA Modifications and Their Functions

| Modification | RNA Targets | Writers | Erasers | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N6-methyladenosine (m6A) | mRNA, lncRNA, miRNA | METTL3/METTL14/WTAP complex | FTO, ALKBH5 | Splicing, export, translation, stability, decay |

| 5-methylcytosine (m5C) | mRNA, tRNA, rRNA | NSUN2, DNMT2 | TET enzymes | Stability, nuclear export, translation initiation |

| N1-methyladenosine (m1A) | tRNA, rRNA | TRMT family | FTO, ALKBH | tRNA folding, ribosome assembly, translational fidelity |

| Pseudouridine (Ψ) | rRNA, tRNA, snRNA | PUS family | Not identified | RNA folding, stability, spliceosome assembly |

| A-to-I Editing | mRNA | ADAR family | Not applicable | Codon alteration, splice site modulation, miRNA targeting |

Experimental Approaches for RNA Modification Research

Sequencing-Based Mapping: Advanced sequencing technologies have been developed to map various RNA modifications. Techniques like meRIP-Seq and miCLIP enable transcriptome-wide mapping of m6A sites, while bisulfite sequencing can be adapted to detect m5C. Direct RNA sequencing using nanopore technology allows for direct detection of multiple modifications without chemical conversion [35] [34].

Mass Spectrometry: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides a highly sensitive method for quantifying the abundance of modified nucleosides in RNA hydrolysates, offering absolute quantification of modification levels [34].

Chemical Probing and Pull-Down: Antibody-based enrichment approaches combined with high-throughput sequencing enable the mapping of modification sites, while chemical-assisted techniques use specific reagents that react differently with modified versus unmodified bases [34].

Therapeutic RNA Editing: A particularly promising experimental application is RNA editing using engineered guide RNAs (gRNAs) to redirect endogenous Adenosine Deaminase Acting on RNA (ADAR) enzymes. This approach enables precise A-to-I (read as A-to-G) conversion at specific sites, allowing researchers to correct disease-causing mutations, modulate splicing, or alter protein function at the RNA level without permanent genomic changes [18].

Diagram 1: The Writer-Eraser-Reader System for RNA Modifications. This regulatory system enables dynamic, reversible control of RNA function through coordinated enzyme activities.

Interplay Between DNA and RNA Modifications in Gene Regulation

DNA and RNA modifications do not function in isolation but rather form a coordinated, multi-layered regulatory network that controls gene expression from chromosome to protein synthesis. Understanding their interplay represents a frontier in epigenetics and epitranscriptomics research.

Sequential Regulation: DNA modifications primarily regulate transcriptional initiation by controlling chromatin accessibility and transcription factor binding, establishing the fundamental potential for gene expression. Subsequently, RNA modifications fine-tune the fate of the transcribed RNA molecules, adding a crucial post-transcriptional regulatory layer that can either reinforce or counteract the transcriptionally defined expression program [30] [34].

Cross-Regulation Between Modification Systems: Evidence suggests that DNA and RNA modification systems can influence each other. For instance, the DNA methyltransferase DNMT2 also functions as an RNA methyltransferase, installing m5C modifications on tRNA. Additionally, several RNA binding proteins that recognize modified RNAs can influence chromatin structure and transcription, potentially creating feedback loops between the two systems [34].

Integrated Stress Response: Under cellular stress, both DNA and RNA modification landscapes undergo coordinated changes that collectively modulate gene expression patterns to promote adaptation. For example, stress-induced changes in DNA methylation can alter the transcription of specific genes, while concurrent changes in RNA modifications can adjust the translation efficiency of stress-response proteins [34] [23].

Technological Advances and Research Methodologies

Advanced Gene Editing and Detection Technologies

Recent technological advances have revolutionized our ability to detect, map, and functionally characterize nucleic acid modifications, driving the discovery of novel modifications and their biological functions.

Prime Editing Advancements: MIT researchers recently developed a significantly improved prime editing system termed vPE. By engineering Cas9 proteins with mutations that relax cutting constraints and degrade old DNA strands more efficiently, they combined these with RNA-binding proteins that stabilize template ends. This breakthrough system reduced error rates from approximately 1 in 7 edits to about 1 in 101 for common editing types, and from 1 in 122 to 1 in 543 for more precise editing modes, representing a 60-fold improvement in accuracy [36].

Nanopore Sequencing for Direct Detection: Third-generation sequencing technologies, particularly nanopore sequencing, enable direct detection of DNA and RNA modifications without chemical conversion steps. By analyzing changes in electrical current signatures as nucleic acids pass through protein nanopores, these platforms can identify modified bases while simultaneously determining the sequence. Tools like DirectRM have been developed to detect landscape and crosstalk between multiple RNA modifications using direct RNA sequencing [35] [32].

Single-Cell and Single-Molecule Approaches: Emerging technologies now enable modification mapping at single-cell resolution, revealing cell-to-cell heterogeneity in modification patterns that are masked in bulk analyses. Single-molecule imaging techniques using specialized immunostaining protocols allow for the detection and quantification of different DNA modifications in individual cells, providing spatial information within the nucleus [32].

Diagram 2: High-Precision Prime Editing Workflow. This next-generation gene editing system enables precise genetic corrections without double-strand breaks, significantly reducing errors compared to previous methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA and RNA Modification Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil for detection of 5mC by sequencing or PCR |

| Methylation-Sensitive Enzymes | HpaII, MspI, McrBC | Restriction enzymes with differential activity based on methylation status for targeted methylation analysis |

| Antibodies for Enrichment | Anti-5mC, Anti-5hmC, Anti-m6A | Immunoprecipitation of modified DNA/RNA for genome-wide or transcriptome-wide mapping |

| Writer/Eraser Recombinant Proteins | METTL3/METTL14 complex, recombinant FTO, DNMTs | In vitro modification installation or removal for functional studies and biochemical characterization |

| CRISPR-Based Editing Systems | dCas9-Tet1/dCas9-DNMT3a, Prime Editors (vPE) | Targeted locus-specific demethylation or methylation; precise gene correction with minimal errors |

| Modified Nucleotide Analogs | 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine, 3-Deazaneplanocin A | Chemical inhibition of DNA methyltransferases or histone methyltransferases for functional studies |

| Guide RNA Systems | ADAR-recruiting RNAs, sgRNAs for dCas9-fusions | Redirecting editing enzymes to specific RNA or DNA targets for programmable modification |

| Direct Sequencing Kits | Oxford Nanopore DNA/RNA sequencing kits | Direct detection of modifications without pre-conversion, enabling long-read modification mapping |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Disease Research

The dynamic and reversible nature of nucleic acid modifications makes them particularly attractive therapeutic targets for various diseases, especially cancer, neurological disorders, and metabolic conditions.