Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): A Comprehensive Guide to Gene Silencing Mechanisms and Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), a transformative class of gene-silencing therapeutics.

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): A Comprehensive Guide to Gene Silencing Mechanisms and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), a transformative class of gene-silencing therapeutics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms of ASO action, from RNase H-mediated degradation to steric hindrance and splice modulation. It details the latest methodological advances in chemical modifications, delivery strategies, and computational design, alongside real-world applications in treating rare genetic and common diseases. The content further addresses critical challenges in stability, delivery, and toxicity, offering optimization strategies and validation frameworks through preclinical models and clinical trial insights. By synthesizing current research, market trends, and future directions, this resource serves as an essential reference for advancing ASO-based therapeutic programs.

The Science of Silence: Unraveling the Core Mechanisms of Antisense Oligonucleotides

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are short, synthetic, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules, typically 13 to 25 nucleotides in length, designed to be perfectly complementary to a specific target messenger RNA (mRNA) sequence through Watson-Crick base pairing [1] [2] [3]. Since the pioneering work of Stephenson and Zamecnik in 1978, who first demonstrated that a short oligonucleotide could inhibit Rous sarcoma virus replication, ASO technology has evolved into a sophisticated therapeutic platform for modulating gene expression at the RNA level [4] [3]. This approach enables precise intervention in the central dogma of biology, targeting the intermediate step between DNA and protein to address the underlying causes of genetic disorders.

ASOs represent a powerful tool in the gene silencing research arsenal, offering a unique combination of high specificity, programmable design, and mechanistic versatility. Their ability to target previously "undruggable" pathways and their applicability to both rare and common diseases have positioned ASOs as a transformative modality in precision medicine, with multiple FDA-approved therapies and a robust pipeline of clinical candidates [4] [5] [2].

Basic Structure and Chemical Modifications

The fundamental structure of an ASO consists of a short chain of nucleosides linked by phosphodiester bonds. Each nucleoside comprises a nitrogenous base (adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, or uracil), a pentose sugar (deoxyribose or ribose), and a phosphate group [1]. However, natural oligonucleotides are highly susceptible to degradation by intracellular nucleases, necessitating chemical modifications to enhance their stability, specificity, and cellular uptake.

Table 1: Common Chemical Modifications in ASO Design

| Modification Type | Description | Primary Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone Modification | Replacement of non-bridging oxygen with sulfur in phosphate group | Increases nuclease resistance and enhances protein binding | Phosphorothioate (PS) |

| Sugar Modification | Modification at the 2' position of the ribose sugar | Enhances binding affinity to target RNA and improves stability | 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) |

| Conjugate Groups | Attachment of specific molecules to the oligonucleotide | Improves targeted delivery to specific tissues or cells | GalNAc (for hepatocyte targeting), lipids, peptides, antibodies |

These chemical modifications are crucial for overcoming the inherent challenges of oligonucleotide therapeutics. Phosphorothioate modifications, for instance, not only increase resistance to nucleases but also promote protein binding, which facilitates cellular uptake and influences tissue distribution [1] [6]. The evolution of ASO chemistry has progressed through generations of improvements, with third-generation modifications like phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) offering enhanced binding affinity and reduced toxicity profiles [1] [3].

Mechanisms of Action

ASOs modulate gene expression through diverse mechanisms, broadly categorized into those that degrade target RNA and those that act through steric blockade without degradation. The specific mechanism employed depends on ASO chemistry, design, and binding location within the target transcript.

RNase H1-Dependent Degradation

This mechanism utilizes gapmer designs, where the ASO contains a central DNA "gap" region flanked by chemically modified RNA-like nucleotides on both ends. Upon hybridization to the target mRNA, the DNA-RNA heteroduplex recruits the ubiquitous cellular enzyme RNase H1, which cleaves the RNA strand, leading to mRNA degradation and subsequent suppression of gene expression [4] [2]. This approach is particularly useful for reducing the expression of pathogenic transcripts in gain-of-function disorders.

Steric Blockade

Steric-blocking ASOs physically obstruct access to specific sequences on the target RNA without inducing degradation. This mechanism enables several sophisticated applications:

- Splicing Modulation: Splice-switching ASOs (SSOs) bind to pre-mRNA and modulate alternative splicing by blocking the binding of splicing factors to regulatory sequences. This can promote exon inclusion (e.g., nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy) or exon exclusion (e.g., eteplirsen for Duchenne muscular dystrophy) [4] [5].

- Translation Inhibition: ASOs can bind to the translation start site or other regulatory regions, physically blocking the ribosomal machinery and preventing protein synthesis [3].

- miRNA Inhibition: ASOs can function as "antagomirs" by binding to and sequestering microRNAs, thereby preventing them from repressing their natural mRNA targets [3].

Targeted Augmentation of Nuclear Gene Output (TANGO)

TANGO strategies represent a novel approach to increase protein production from specific genes through ASO-mediated mechanisms:

- Targeting Poison Exons: ASOs can block the splicing of naturally occurring "poison exons" that would otherwise lead to non-productive mRNA, thereby increasing functional mRNA and protein levels [4].

- Blocking Translational Repressive Elements: ASOs can bind to upstream open reading frames (uORFs) or other translation-suppressive motifs within mRNA untranslated regions (UTRs), relieving repression and enhancing translation of the main coding sequence [4] [3].

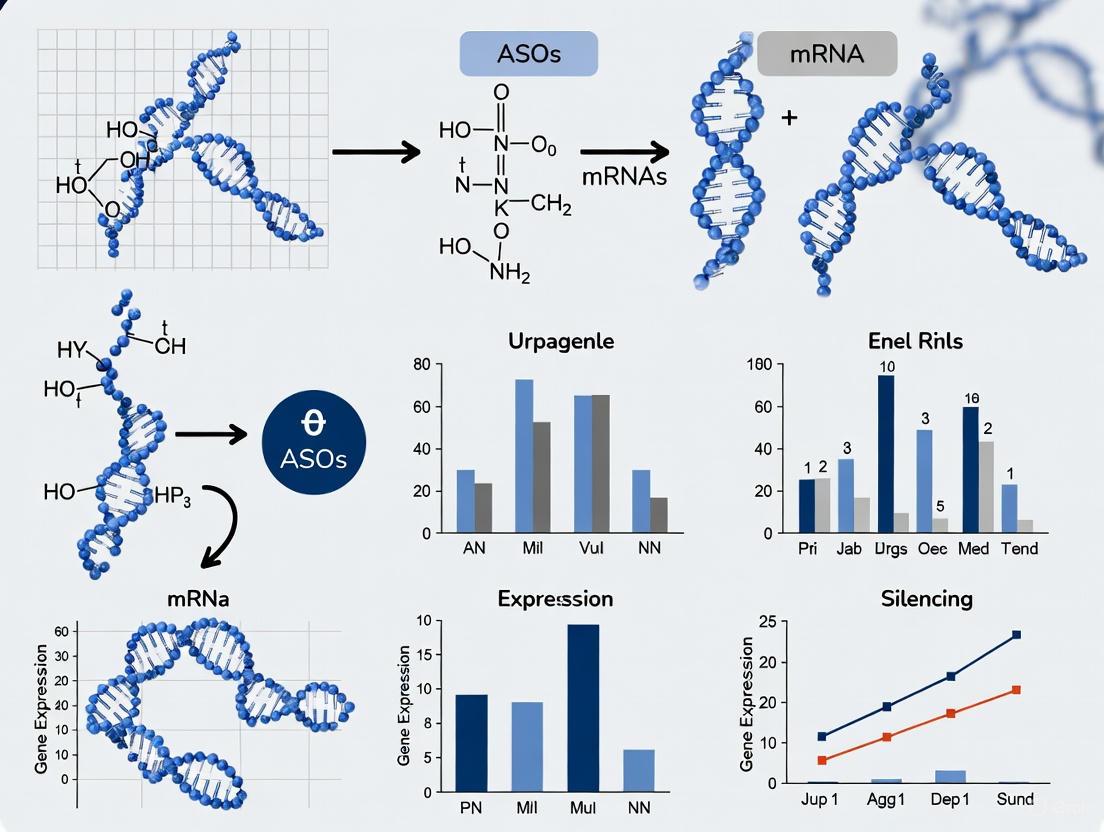

Diagram 1: Diverse Mechanisms of ASO Action. ASOs can modulate gene expression through degradation, steric blockade, or upregulation pathways depending on their design and cellular context.

ASO Synthesis and Design Considerations

Synthesis Protocol

ASO synthesis primarily utilizes solid-phase phosphoramidite chemistry, which enables efficient, stepwise oligonucleotide assembly [1]. The detailed protocol involves the following steps:

Deprotection: The 5'-end protecting group (typically dimethoxytriphenyl, DMT) is removed using trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or dichloroacetic acid (DCA), preparing the growing chain for nucleotide addition.

Coupling: The 3'-OH of the incoming phosphoramidite monomer is activated by tetrazole, forming a reactive intermediate that links to the 5'-end of the support-bound oligonucleotide chain.

Capping: Any unreacted 5'-OH groups (failed couplings) are blocked ("capped") with acetic anhydride and N-methylimidazole to prevent the formation of deletion sequences in subsequent cycles.

Oxidation: The newly formed phosphite triester linkage is oxidized to a more stable phosphate (or phosphorothioate) using iodine/water or a sulfurization reagent.

Cleavage and Deprotection: After complete sequence assembly, the oligonucleotide is cleaved from the solid support (typically controlled pore glass, CPG) and all protecting groups are removed under specific conditions.

This synthetic approach enables the production of high-quality ASOs with various modifications, though careful purification is required to remove truncated sequences, longer sequences, and other impurities that may form during synthesis [1].

Critical Design Considerations

Successful ASO design requires attention to multiple factors beyond simple sequence complementarity:

Target Accessibility: mRNA folds into secondary and tertiary structures that can impede ASO binding. Target sites should be selected in unpaired regions, which can be predicted computationally or identified experimentally through methods like RNase H mapping [1] [7].

Sequence Specificity: ASOs should be designed to uniquely target the intended RNA sequence. BLAST analysis is recommended to ensure minimal off-target hybridization to unrelated transcripts [1].

Avoidance of Immunostimulatory Motifs: Unmethylated CpG dinucleotides can stimulate immune responses and should be avoided in ASO design [1].

Thermodynamic Properties: GC content and secondary structure formation of the ASO itself should be optimized to balance binding affinity and specificity.

Advanced design approaches are emerging, including structure-based methods that consider the three-dimensional architecture of target RNAs. These "3D-ASO" designs employ tertiary interaction templates derived from natural RNA structures like pseudoknots, enabling enhanced affinity and specificity for structured target sites [7].

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Protocols

ASOs have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential across diverse disease areas, particularly for monogenic disorders. Their application spans neurogenetic, metabolic, and oncologic disorders, with emerging n-of-1 approaches for ultra-rare conditions [4].

Table 2: Selected Approved ASO Therapies and Their Applications

| Drug Name | Target Condition | Mechanism | Administration Route | Key Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nusinersen (Spinraza) | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | Splicing modulation of SMN2 gene | Intrathecal | Improved motor function in infants and children |

| Eteplirsen (Exondys 51) | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | Exon skipping in dystrophin gene | Intravenous | Increased dystrophin production |

| Tofersen (Qalsody) | SOD1-ALS | RNase H-mediated degradation of mutant SOD1 mRNA | Intrathecal | Reduced SOD1 protein levels in CSF |

| Inotersen (Tegsedi) | hATTR Amyloidosis | RNase H-mediated knockdown of TTR mRNA | Subcutaneous | Improved neuropathy and quality of life |

Administration and Delivery Protocols

Effective ASO delivery remains a critical consideration in therapeutic development:

Central Nervous System Delivery: Intrathecal administration bypasses the blood-brain barrier, allowing ASOs to directly reach neurons and glial cells in the brain and spinal cord. The slow clearance from cerebrospinal fluid enables sustained effects with intermittent dosing [4]. Clinical protocols for nusinersen, for example, involve loading doses followed by maintenance dosing every four months.

Hepatic Delivery: The liver efficiently takes up ASOs via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Systemic administration (intravenous or subcutaneous) is effective for hepatocyte targets, with conjugation to GalNAc ligands significantly enhancing delivery specificity and potency through engagement with the asialoglycoprotein receptor [4] [8].

Emerging Delivery Strategies: Chemically inducible ASOs (iASOs) represent an innovative approach for cell-selective activation. For example, phenylboronic acid-caged iASOs remain inactive until triggered by hydrogen peroxide, enabling tumor-cell-selective gene silencing [9]. Additionally, antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates and nanoparticle formulations are being developed for tissue-specific targeting [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ASO Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphoramidite Reagents | Building blocks for ASO synthesis | DNA/RNA phosphoramidites with protective groups (DMT, β-cyanoethyl) for solid-phase synthesis |

| Chemical Modification Reagents | Introduce nuclease resistance and enhance binding | Phosphorothioate reagents, 2'-O-methyl, 2'-MOE, LNA phosphoramidites for ASO optimization |

| Delivery/Targeting Reagents | Facilitate cellular uptake and tissue-specific delivery | GalNAc conjugation reagents, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), cell-penetrating peptides |

| Solid Support Materials | Platform for automated oligonucleotide synthesis | Controlled pore glass (CPG) beads with appropriate linkers for various synthesis scales |

| Analytical Standards | Quality control and quantification | HPLC standards, reference materials for purity assessment and bioanalytical method development |

| Enzymatic Tools | Mechanism of action studies | Recombinant RNase H1, Argonaute 2 (Ago2) for in vitro characterization of ASO activity |

Comparison with Other Gene Silencing Modalities

ASOs are often compared with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), another prominent oligonucleotide therapeutic platform. While both modalities achieve gene silencing through sequence-specific RNA targeting, they differ in several key aspects:

Diagram 2: Comparative Analysis of ASO and siRNA Platforms. While both are oligonucleotide therapeutics, ASOs and siRNAs differ in fundamental properties and therapeutic applications.

ASOs offer distinct advantages for certain applications, particularly their ability to target nuclear RNAs, achieve allele-selective silencing for dominant disorders, and employ multiple mechanisms beyond simple degradation [6]. However, both platforms continue to evolve with improvements in chemistry and delivery systems.

Antisense oligonucleotides have matured from a theoretical concept to a validated therapeutic platform with multiple approved drugs and a robust clinical pipeline. Their precise mechanism of action, programmability, and ability to target previously undruggable pathways position ASOs as powerful tools in the gene silencing research arsenal and precision medicine.

Future developments in ASO technology will likely focus on overcoming remaining challenges, particularly delivery to tissues beyond the liver and central nervous system. Innovations in conjugate chemistry, cell-specific activation strategies (such as iASOs), and advanced formulations will expand the therapeutic reach of ASOs [9] [8]. Furthermore, structure-based design approaches that account for RNA three-dimensional architecture promise to enhance the efficiency and specificity of future ASO therapeutics [7].

As the field advances, ASOs are poised to make increasingly significant contributions to the treatment of genetic disorders, cancer, and other diseases with well-defined molecular targets, ultimately fulfilling their potential as a versatile and precise modality for genetic medicine.

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are short, synthetic, single-stranded nucleic acids, typically 13-30 nucleotides in length, designed to modulate gene expression by binding to target RNA molecules via Watson-Crick base pairing [10] [11] [3]. They represent a powerful therapeutic platform for treating genetic disorders, with multiple drugs receiving FDA approval. ASOs primarily function through two distinct mechanistic categories: those that enzymatically degrade their target RNA (e.g., RNase H-mediated degradation) and those that sterically hinder cellular processes without degrading the RNA [10] [12]. The choice between these mechanisms depends on the therapeutic goal, target RNA sequence, and cellular context, and is fundamentally determined by the ASO's chemical design [10] [11].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic divergence between these two primary ASO action pathways.

RNase H-Mediated Degradation Pathway

Mechanism and Molecular Machinery

RNase H-mediated degradation is an enzymatic mechanism that results in the cleavage and destruction of the target RNA [10] [13]. This pathway is initiated when a DNA-like ASO base-pairs with its complementary target mRNA to form an RNA-DNA heteroduplex [10]. This heteroduplex is then recognized by the cellular enzyme RNase H1, an endonuclease present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm [10] [13]. RNase H1 cleaves the RNA strand within the heteroduplex region, leading to subsequent degradation of the mRNA by cellular exonucleases [10]. The resulting mRNA fragments, lacking protective 5'-cap and poly-A tail structures, are rapidly degraded, preventing translation of the encoded protein [13].

The efficiency of RNase H cleavage depends on several factors, including the length and stability of the RNA-DNA hybrid, with more stable, perfectly complementary hybrids promoting stronger RNase H binding and cleavage activity [13]. This mechanism is particularly exploited by gapmer ASOs, which contain a central DNA "gap" region (typically 8-10 deoxynucleotides) flanked by modified RNA nucleotides that confer nuclease resistance and enhance binding affinity but do not support RNase H activity [11] [12].

Experimental Protocol for RNase H-Dependent ASOs

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of RNase H-dependent ASOs in reducing target mRNA levels in mammalian cell culture.

Materials:

- Gapmer ASOs: Design with 16-20 nucleotide length, including 8-10 DNA nucleotides in the central gap, flanked by 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) or LNA-modified wings [11] [13].

- Cell Line: Appropriate mammalian cell line expressing the target mRNA.

- Transfection Reagent: Cytofectin or Lipofectamine RNAiMAX [14].

- Lysis Buffer: RIPA buffer for protein isolation, RLT buffer for RNA isolation [14].

- Analysis Reagents: Primers for qRT-PCR, antibodies for Western blot.

Procedure:

- ASO Design and Preparation: Design gapmer ASOs complementary to the target mRNA region. Include appropriate negative control ASOs with scrambled sequences.

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells in appropriate culture media 24 hours before transfection to achieve 60-80% confluency.

- Transfection: Transfect cells with 50 nM ASO using 3 μg/mL Cytofectin transfection reagent for 24 hours [14].

- RNA Isolation: Harvest total cellular RNA using RNeasy kit 24-48 hours post-transfection.

- qRT-PCR Analysis: Perform quantitative RT-PCR using approximately 10 ng RNA with TaqMan primer and probe sets specific to the target mRNA. Normalize to Ribogreen or housekeeping genes [14].

- Protein Analysis: Isolate protein using RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors. Perform Western blot with 10-40 μg protein lysate to confirm reduction of target protein [14].

- Data Analysis: Calculate mRNA reduction using the relative standard curve method compared to negative control ASOs.

Steric Hindrance Mechanism

Mechanism and Functional Outcomes

In contrast to RNase H-mediated degradation, steric hindrance ASOs function without degrading the target RNA by physically blocking access to specific sequence elements or protein-binding sites [10] [11]. These ASOs are fully modified with chemical groups such as 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), or phosphorodiamidate morpholino (PMO) throughout their sequence, making them resistant to RNase H recognition while increasing target affinity and nuclease stability [14] [15]. The therapeutic effects are achieved through several mechanisms:

- Splice Modulation: ASOs bind to splice regulatory elements (donor/acceptor sites, branch points, enhancers, or silencers) in pre-mRNA, redirecting splicing machinery to promote exon inclusion or exclusion [10] [12]. This approach can restore reading frames or skip exons containing disease-causing mutations.

- Translational Blockade: ASOs binding to the 5' untranslated region (UTR) or start codon can sterically hinder ribosome assembly or scanning, preventing translation initiation [10] [3].

- Modulation of RNA Function: ASOs can block regulatory elements such as upstream open reading frames (uORFs) or microRNA binding sites, thereby increasing translation of the main ORF [11] [3].

- Indirect Degradation Pathways: Some steric-blocking ASOs can be designed to promote aberrant splicing that introduces premature termination codons (PTCs), leading to transcript degradation via the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway [14].

Experimental Protocol for Steric-Blocking ASOs

Objective: To assess the splice-modulating activity of steric-blocking ASOs in cell culture.

Materials:

- Steric-Blocking ASOs: Fully modified 18-25 nucleotide ASOs with 2'-OMe, 2'-MOE, or PMO modifications [14] [15].

- Cell Line: HeLa or other relevant cell lines expressing the target pre-mRNA.

- Transfection Reagent: Lipofectamine RNAiMAX or Cytofectin.

- RNA Isolation Kit: RNeasy kit or equivalent.

- RT-PCR Reagents: Reverse transcriptase, PCR polymerase, gel electrophoresis equipment.

Procedure:

- ASO Design: Design ASOs complementary to splice acceptor/donor sites, exonic splicing enhancers, or silencers of the target pre-mRNA.

- Cell Transfection: Plate cells and transfect with 50 nM ASO using appropriate transfection reagent for 24 hours [14].

- RNA Isolation: Harvest total RNA 24-48 hours post-transfection.

- RT-PCR Analysis: Reverse transcribe 400 ng RNA using random hexamers. Perform PCR with primers flanking the target exon.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Resolve PCR products on 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels and stain with ethidium bromide [14].

- Quantification: Image gels and calculate the percentage of exon skipping/inclusion using band intensity: [exon exclusion band / (inclusion band + exclusion band)] × 100, with correction for DNA content per band [14].

- Validation: Sequence PCR products to confirm accurate splicing patterns.

Comparative Analysis: Key Distinctions

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between RNase H-mediated degradation and steric hindrance mechanisms, highlighting their distinct applications, design requirements, and experimental considerations.

| Parameter | RNase H-Mediated Degradation | Steric Hindrance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Enzymatic cleavage of target RNA [10] [13] | Physical blockade of RNA function [10] [11] |

| Effect on Target RNA | Degradation [10] | Modification of function/splicing; no degradation [10] |

| ASO Chemical Structure | Gapmer (DNA core with modified flanking regions) [11] [12] | Fully modified (uniform 2'-MOE, 2'-OMe, PMO, etc.) [14] |

| Therapeutic Applications | Reducing expression of toxic proteins [12] | Exon skipping, splice correction, translation modulation [10] [12] |

| Cellular Localization | Nucleus and cytoplasm [10] | Primarily nucleus for splicing modulation [10] |

| Key Enzymes/Pathways | RNase H1 [10] [13] | Spliceosome, NMD pathway (indirectly) [14] |

| Experimental Readout | mRNA reduction (qRT-PCR), protein reduction (Western) [14] | Splicing changes (RT-PCR), protein isoform detection [14] |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points for researchers when selecting between these two fundamental ASO mechanisms for their experimental or therapeutic goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of ASO experiments requires specific reagent solutions designed for nucleic acid therapeutics research. The table below outlines key materials and their functions.

| Research Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Gapmer ASOs (DNA core with 2'-MOE/LNA wings) | Enable RNase H-mediated target RNA degradation [11] [12] |

| Steric-Blocking ASOs (fully modified 2'-OMe, PMO) | Modulate splicing or translation without degradation [14] [15] |

| Cytofectin Transfection Reagent | Efficient delivery of ASOs into mammalian cells [14] |

| RNeasy Kit | High-quality total RNA isolation for downstream qRT-PCR and splicing analysis [14] |

| TaqMan Primer/Probe Sets | Specific detection and quantification of target mRNA levels via qRT-PCR [14] |

| RNase H1 Enzyme | In vitro validation of gapmer ASO mechanism and activity [13] |

RNase H-mediated degradation and steric hindrance represent two fundamental, mechanistically distinct approaches for ASO-based gene regulation. The RNase H pathway is ideal for applications requiring reduction of specific RNA transcripts, particularly for gain-of-function mutations where decreasing protein levels is therapeutic [12]. In contrast, steric hindrance ASOs offer precise control over RNA processing through splice modulation and translational regulation, making them suitable for restoring functional protein expression in loss-of-function disorders [10] [12]. The choice between these mechanisms directly influences ASO design, chemical modification strategy, experimental protocols, and expected outcomes. Understanding these distinctions enables researchers to strategically select the optimal approach for their specific research objectives in gene function studies or therapeutic development.

Application Notes: Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Landscape

Splicing modulation therapies, particularly those utilizing antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), have emerged as a powerful precision medicine platform for treating genetic disorders caused by loss-of-function mutations. These therapies function by manipulating the natural process of pre-mRNA splicing to correct disease-causing genetic errors, either by excluding problematic exons or including critical ones to restore functional protein expression [16] [17].

FDA-Approved Exon-Skipping Therapies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

The most advanced clinical application of exon skipping is for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an inherited progressive muscle disease caused by variants in the DMD gene that disrupt the reading frame of dystrophin mRNA [18] [19]. ASO-mediated exon skipping converts out-of-frame deletions to in-frame deletions, enabling the production of partially functional dystrophin proteins [18].

Table 1: FDA-Approved Exon-Skipping Therapies for DMD

| Therapeutic Agent | Target Exon | Year Approved | Mechanism | Patient Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eteplirsen [16] [18] | Exon 51 | 2016 (Accelerated Approval) | Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO) that binds exon 51 splicing enhancer | ~13% of DMD patients amenable to exon 51 skipping |

| Golodirsen [16] [20] | Exon 53 | 2019 (Accelerated Approval) | PMO that induces exclusion of exon 53 from mature mRNA | ~8% of DMD patients amenable to exon 53 skipping |

| Viltolarsen [16] [17] | Exon 53 | 2020 (Accelerated Approval) | PMO that binds regulatory elements to promote exon 53 skipping | ~8% of DMD patients amenable to exon 53 skipping |

| Casimersen [16] [20] | Exon 45 | 2021 (Accelerated Approval) | PMO designed to skip exon 45 during pre-mRNA processing | ~8% of DMD patients amenable to exon 45 skipping |

The confirmatory Phase 3 ESSENCE trial (96 weeks) for golodirsen and casimersen recently completed, reporting numerical trends favoring treatment over placebo despite not achieving statistical significance on the primary endpoint (4-step ascend velocity). Importantly, when excluding participants impacted by COVID-19-related dosing interruptions (43% of cohort), the data demonstrated clinically meaningful slowing of disease progression [20].

Exon Inclusion Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Splice-switching ASOs can also promote beneficial exon inclusion, as exemplified by nusinersen (Spinraza) for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [17]. SMA is caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene. Nusinersen targets the SMN2 pre-mRNA to promote inclusion of exon 7, resulting in increased production of full-length, functional SMN protein and dramatically improved patient outcomes [17] [21].

Emerging Applications in Oncology

Aberrant RNA splicing is a molecular hallmark present in almost all cancer types, with tumors exhibiting up to 30% more alternative splicing events than normal tissues [22]. This creates new therapeutic opportunities for splice-modulating ASOs to:

- Correct cancer-specific aberrant splicing that drives tumorigenesis [22]

- Generate neoantigens that enhance immunotherapeutic responses [22]

- Reverse splicing events that confer resistance to conventional therapies [22]

Table 2: Key Splicing Aberrations and Therapeutic Opportunities in Cancer

| Splicing Factor/Alteration | Cancer Type | Functional Consequence | Therapeutic Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRSF1 Upregulation [22] | Lung, Pancreatic, Brain, Breast | Promotes oncogenic isoform switching | ASO-mediated silencing or splice correction |

| SRSF3 Overexpression [22] | Breast, Cervical, Nasopharyngeal | Enhances cancer cell proliferation | Targeted exon skipping or inclusion |

| hnRNPA1 Dysregulation [22] | Multiple Solid Tumors | Promotes PKM2 isoform, enhancing glycolysis | Splice-switching to favor PKM1 isoform |

| Mutations in SF3B1, U2AF1, SRSF2 [22] | Hematological malignancies, Solid tumors | Disrupted splice site recognition | Corrective ASOs or small molecule inhibitors |

Protocols: Experimental Framework for Splice-Modulating ASO Development

Protocol 1: In Silico Prediction and Design of Splice-Switching ASOs

Purpose: To computationally identify and prioritize splice-disruptive variants and design candidate ASOs for experimental validation.

Background: An estimated 15-30% of all disease-causing mutations affect splicing through disruption of canonical splice sites, activation of cryptic sites, or alteration of regulatory elements [17]. Genome-first approaches using whole-genome sequencing enable systematic detection of these variants.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA or whole-genome sequencing data

- Splicing prediction software (e.g., SpliceAI, ESEfinder, NNSPLICE)

- ASO design platform

Procedure:

Variant Identification: Annotate whole-genome sequencing data using pipelines that incorporate deep learning-based splicing prediction models (e.g., SpliceAI) to score potential splice-disruptive effects of variants, including deep-intronic and synonymous changes [17].

Variant Prioritization: Filter and prioritize variants based on:

- Predicted impact on splicing regulatory elements (ESEs, ESSs, ISEs, ISSs)

- Evolutionary conservation of affected nucleotides

- Population allele frequency

- Proximity to exon-intron boundaries [17]

ASO Target Selection: Identify optimal ASO binding sites within pre-mRNA that:

ASO Sequence Design: Design 15-25 nucleotide ASOs with:

- Perfect complementarity to the target pre-mRNA region

- Appropriate chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl, 2'-MOE, PMO) for enhanced stability and binding affinity [21]

Figure 1: Computational workflow for predicting splice-disruptive variants and designing targeted ASOs.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Splicing Correction

Purpose: To empirically test the efficacy of candidate ASOs in modulating splicing patterns in cellular models.

Background: ASOs act through steric blockade to prevent spliceosomal components or regulatory factors from accessing pre-mRNA targets. For DMD, ASOs bind to splicing enhancer sequences within exons, leading to exon exclusion and restoration of the dystrophin reading frame [18] [19].

Materials:

- Patient-derived fibroblasts or myoblasts

- Control cell lines (wild-type)

- Candidate ASOs and scrambled control ASOs

- Transfection reagent

- RNA extraction kit

- RT-PCR reagents

- Gel electrophoresis system

- Western blot apparatus

- Dystrophin-specific antibodies (for DMD models)

Procedure:

Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Culture patient-derived cells (e.g., fibroblasts or myoblasts) harboring the target mutation in appropriate growth media.

- Transfect cells with candidate ASOs (0.1-100 nM range) using lipid-based transfection reagents. Include untransfected and scrambled ASO controls.

- Incubate cells for 24-72 hours to allow splicing modulation.

RNA Analysis:

- Extract total RNA using silica-membrane columns.

- Perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA.

- Amplify target region by PCR using primers flanking the exon of interest.

- Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis to visualize splicing patterns:

- Successful exon skipping will yield a shorter PCR product.

- Successful exon inclusion will yield a longer PCR product.

- Quantify band intensity to determine splicing correction efficiency.

Protein Analysis (for DMD models):

- Lyse cells for protein extraction 48-96 hours post-transfection.

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to membranes.

- Probe membranes with dystrophin-specific antibodies to detect restored protein expression.

- Compare expression levels to wild-type controls and untreated cells.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for validating ASO-mediated splicing correction in cellular models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Splice-Modulation Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| ASO Chemistries [21] | Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs), 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) | Backbone modifications that enhance nuclease resistance, improve binding affinity, and reduce toxicity |

| Delivery Systems [2] | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), GalNAc conjugates, Dynamic polyconjugates | Enhance cellular uptake and targeted delivery of ASOs to specific tissues (e.g., liver, muscle) |

| Cell Models [17] | Patient-derived fibroblasts, Myoblasts, Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) | Provide physiologically relevant systems for testing ASO efficacy and mechanism of action |

| Splicing Prediction Tools [17] | SpliceAI, ESEfinder, NNSPLICE | Computational platforms to predict splice-disruptive variants and optimize ASO target sequences |

| Validation Reagents | Splice-junction specific primers, Isoform-specific antibodies | Enable detection and quantification of successful splicing correction at RNA and protein levels |

Molecular Mechanism of Splice-Switching ASOs

Figure 3: Molecular mechanism of splice-switching ASOs. ASOs bind pre-mRNA to sterically block splicing regulatory elements, leading to either exon skipping or inclusion.

Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) technology represents a transformative approach for modulating gene expression through sequence-specific targeting of RNA. This application note details the historical evolution, molecular mechanisms, and standardized protocols for implementing ASO therapies in research and clinical settings. We provide a comprehensive timeline of key developments from conceptual origins to approved therapies, along with experimental workflows and reagent specifications to support drug development professionals in leveraging this powerful technology. The content is structured to facilitate practical implementation while contextualizing advances within the broader framework of genetic medicine.

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are short, synthetic, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules designed to bind complementary target RNA sequences through Watson-Crick base pairing, enabling precise control of gene expression at multiple regulatory levels [3]. Since their conceptualization, ASOs have evolved from laboratory tools to sophisticated therapeutics capable of addressing previously undruggable genetic targets.

The fundamental principle of ASO technology involves designing oligonucleotides complementary to specific RNA targets, which upon binding can modulate RNA function through various mechanisms including RNase H-mediated degradation, steric blockade, and splice modulation [23] [12]. This versatility has established ASOs as invaluable tools for functional genomics and as promising therapeutic modalities for monogenic disorders, with 15 oligonucleotide drugs having received market authorization as of 2024 [12].

This document provides researchers with both historical context and practical methodologies for implementing ASO technologies, emphasizing the progression from basic research to clinical application.

Historical Timeline of ASO Development

The development of ASO technology spans nearly five decades, marked by key conceptual, technical, and clinical breakthroughs. The table below summarizes major milestones in ASO evolution.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key ASO Developments

| Year | Development | Significance | Key Researchers/Organizations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | First demonstration of antisense principle | Synthetic oligonucleotide inhibited Rous sarcoma virus replication [23] [24] | Zamecnik and Stephenson |

| 1979 | RNase H mechanism described | Established enzyme-mediated degradation of RNA in DNA-RNA hybrids [24] | Donis-Keller |

| 1980s | Phosphorothioate backbone modification | Greatly improved nuclease resistance and pharmacokinetics [23] [25] | Multiple groups |

| 1998 | First ASO drug approved (Fomivirsen) | Approved for CMV retinitis; validated ASOs as therapeutics [24] [26] [25] | FDA/EMEA |

| 2000s | Advanced chemical modifications (2'-MOE, LNA) | Enhanced binding affinity and specificity [23] | Multiple groups |

| 2011-2016 | Splice-switching ASOs approved | Eteplirsen (2016) for DMD; Nusinersen (2016) for SMA [26] [25] | FDA/EMEA |

| 2018-2023 | Expansion to neurodegenerative diseases | Inotersen (2018) for amyloidosis; Tofersen (2023) for ALS [25] | FDA/EMEA |

The initial concept of "complementary-addressed modification" was formulated in 1967 by Grineva, who proposed that attaching active chemical groups to oligonucleotides could direct them to specific nucleic acid fragments [24]. However, the field languished until the late 1970s due to challenges with oligonucleotide synthesis, cellular delivery, and limited genomic sequence information [24].

The modern era of ASO technology began with Zamecnik and Stephenson's 1978 demonstration that a synthetic 13-mer oligodeoxynucleotide could inhibit Rous sarcoma virus replication [23] [24]. This established the core antisense principle and suggested therapeutic potential. The subsequent discovery that RNase H cleaves the RNA strand of DNA-RNA hybrids provided a crucial mechanistic foundation for ASO activity [24].

The first-generation ASO chemical modification—phosphorothioate (PS) linkages—significantly improved stability against nuclease degradation and enhanced protein binding for better tissue distribution [23] [25]. The first ASO drug, fomivirsen (Vitravene), approved in 1998, targeted cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS patients and validated the entire therapeutic approach [26] [25].

Second-generation modifications (2'-O-alkyl RNAs like 2'-O-methyl and 2'-O-methoxyethyl) further improved binding affinity and nuclease resistance [23]. The most significant advance came with locked nucleic acid (LNA) and other bridged nucleic acids (BNAs), which dramatically increased affinity for complementary sequences [23].

The clinical landscape expanded with splice-switching ASOs, particularly for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (eteplirsen, 2016) and spinal muscular atrophy (nusinersen, 2016) [26] [25]. Most recently, ASOs have addressed neurodegenerative diseases including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (tofersen, 2023) [25].

Molecular Mechanisms of ASO Action

ASOs employ diverse mechanisms to modulate gene expression, determined by their chemical properties and target sites. The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanistic pathways.

Diagram 1: Primary Mechanisms of ASO Action. ASOs function through multiple pathways depending on their design and cellular localization, leading to either mRNA degradation or modulation of protein function. Abbreviations: ssASOs: splice-switching ASOs; RISC: RNA-induced silencing complex.

Key Mechanistic Pathways

RNase H-Mediated Degradation

Gapmer ASOs contain a central DNA region flanked by modified nucleotides (e.g., 2'-MOE or LNA). The DNA segment forms heteroduplexes with target mRNA, recruiting RNase H1 which cleaves the RNA strand [23] [12]. This pathway primarily operates in the nucleus and results in sustained reduction of target RNA levels.

Splice Modulation

Splice-switching ASOs (ssASOs) bind to pre-mRNA sequences and modulate splicing by blocking splice regulatory elements (splice sites, branch points, enhancers, or silencers) [12]. This can cause exon inclusion or exclusion, potentially restoring reading frames or altering protein isoforms. Successful applications include nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy, which promotes inclusion of exon 7 in SMN2 transcripts [26].

Steric Blockade

ASOs can physically block ribosome assembly, translation initiation, or protein binding without degrading the target RNA [23]. This mechanism is employed by chemically modified ASOs (e.g., 2'-O-alkyl, PMO, PNA) that do not activate RNase H.

RNA Interference Pathway

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), while distinct from single-stranded ASOs, represent a related oligonucleotide therapeutic approach. siRNAs are double-stranded and operate through the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) in the cytoplasm, leading to sequence-specific mRNA cleavage [23] [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful ASO experimentation requires carefully selected reagents and controls. The table below outlines essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ASO Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASO Chemistries | Phosphorothioate (PS), 2'-O-Methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA), Phosphorodiamidate Morpholino Oligomer (PMO) | Determine nuclease resistance, binding affinity, cellular uptake, and mechanism of action | PS improves stability; LNA increases affinity; PMO enables steric blockade [23] |

| Delivery Reagents | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), GalNAc conjugates | Enhance cellular uptake and target tissue delivery | GalNAc conjugates enable hepatocyte-specific targeting [25] |

| Control ASOs | Scrambled sequence, Mismatch control, Sense strand control | Verify sequence-specific effects and rule out off-target impacts | Should have same length and chemistry as active ASO [23] |

| Enzymatic Assays | RNase H activity assays, Quantitative RT-PCR | Measure target reduction and mechanistic validation | Essential for gapmer ASO characterization [23] |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary cells, Immortalized lines, Patient-derived cells | Provide biologically relevant testing systems | Patient-derived cells crucial for rare disease modeling [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vitro Screening of ASO Efficacy

This protocol outlines standardized methodology for initial ASO screening in cell culture systems.

Materials Required

- Synthetic ASOs (≥95% purity, desalted)

- Appropriate cell line expressing target RNA

- Transfection reagent (e.g., lipofectamine)

- Serum-free medium

- Lysis buffer for RNA extraction

- qRT-PCR reagents for target quantification

Procedure

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells in 24-well plates at 50-70% confluence 24 hours before transfection.

- ASO Preparation: Dilute ASOs to 1-10µM stock solutions in nuclease-free water.

- Complex Formation:

- Dilute ASO in serum-free medium (50µL total)

- Dilute transfection reagent separately in serum-free medium (50µL total)

- Combine diluted ASO and transfection reagent, incubate 15-20 minutes at room temperature

- Transfection:

- Add complexes dropwise to cells

- Incubate 4-6 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂

- Replace with complete medium

- Harvesting: Collect cells 24-48 hours post-transfection for RNA analysis.

- Analysis: Extract total RNA and quantify target reduction via qRT-PCR normalized to housekeeping genes.

Key Parameters

- Include appropriate controls (scrambled ASO, untreated cells, transfection control)

- Test multiple ASOs targeting different regions of the same transcript

- Optimize ASO concentration (typically 10-100nM) and transfection conditions

- Perform dose-response and time-course experiments for lead ASOs

Protocol: Assessing Splice-Modulating ASOs

This protocol specifically addresses validation of splice-switching ASOs.

Additional Materials

- Primers flanking alternative exon

- Gel electrophoresis or capillary electrophoresis system

- RNA extraction kit with DNase treatment

- RT-PCR reagents

Procedure

- Transfection: Follow steps 1-5 from Protocol 5.1.

- RNA Extraction: Isolve total RNA using silica-membrane columns with on-column DNase digestion.

- RT-PCR:

- Perform reverse transcription with oligo(dT) or random hexamers

- Conduct PCR with primers spanning the targeted splice region

- Use limited cycle number (25-30) to maintain quantitative range

- Product Analysis:

- Separate PCR products by agarose gel or capillary electrophoresis

- Quantify band intensities to calculate exon inclusion/skipping ratios

- Validation: Confirm altered splice variants by Sanger sequencing.

Protocol: In Vivo Administration in Rodent Models

For therapeutic development, in vivo evaluation is essential. The workflow below outlines the key steps in this process.

Diagram 2: In Vivo ASO Evaluation Workflow. The process involves careful design, formulation, and administration followed by comprehensive analysis to determine therapeutic efficacy.

Materials

- Purified, sterile ASO in saline or PBS

- Animal model (e.g., transgenic mice, xenograft models)

- Appropriate injection apparatus (syringes, pumps, catheters)

- Tissue collection supplies (fixatives, frozen storage tubes)

Procedure

- Dose Preparation: Calculate ASO dose based on animal weight (typically 1-100mg/kg). Prepare fresh solutions in sterile PBS.

- Administration:

- Systemic delivery: Inject via tail vein (mice) or peripheral vein (larger animals)

- CNS delivery: Intracerebroventricular or intrathecal injection

- Local delivery: Subretinal, intramuscular, or topical application

- Dosing Regimen: Single or multiple doses depending on ASO pharmacokinetics and study objectives.

- Monitoring: Observe animals for adverse effects; monitor weight and activity.

- Tissue Collection: Harvest target tissues at predetermined timepoints; snap-freeze for molecular analysis or fix for histology.

- Analysis:

- Quantify target reduction (qRT-PCR, Western blot)

- Assess pharmacokinetics (ASO concentration in tissues)

- Evaluate phenotypic improvements (behavior, histopathology, biomarkers)

Clinical Applications and Approved Therapies

ASO therapeutics have received regulatory approval for multiple genetic disorders, demonstrating the clinical translation of this technology.

Table 3: Selected Approved ASO Therapies and Applications

| Drug Name | Target Condition | Mechanism of Action | Target Gene | Year Approved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fomivirsen | CMV retinitis | RNase H-mediated degradation of viral mRNA | CMV immediate-early gene | 1998 [26] [25] |

| Mipomersen | Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia | RNase H-mediated reduction of apoB-100 mRNA | APOB | 2013 [26] [25] |

| Eteplirsen | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Exon skipping to restore reading frame | Dystrophin exon 51 | 2016 [26] [25] |

| Nusinersen | Spinal muscular atrophy | Exon inclusion to produce functional SMN protein | SMN2 exon 7 | 2016 [26] [25] |

| Inotersen | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | RNase H-mediated reduction of mutant TTR | TTR | 2018 [26] [25] |

| Tofersen | SOD1-ALS | RNase H-mediated reduction of mutant SOD1 | SOD1 | 2023 [25] |

The clinical success of ASOs has been particularly notable for monogenic disorders with well-characterized genetic causes [12]. The approval of nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy represented a breakthrough, demonstrating that ASOs could effectively target the central nervous system when administered intrathecally [26]. Similarly, the development of eteplirsen and subsequent exon-skipping ASOs for Duchenne muscular dystrophy established splice modulation as a viable therapeutic strategy [26].

More recently, the accelerated approval of tofersen for SOD1-associated ALS highlighted the potential of ASOs to address neurodegenerative diseases, with ongoing clinical trials investigating applications for Huntington's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease [25].

ASO technology has evolved from a conceptual framework to a robust therapeutic platform with demonstrated clinical efficacy. The continued refinement of chemical modifications, delivery strategies, and target selection promises to expand applications to additional genetic disorders. This application note provides researchers with historical context, mechanistic insights, and standardized protocols to facilitate further advancement in this rapidly evolving field. As ASO technologies continue to mature, they offer unprecedented opportunities for precise modulation of gene expression and personalized therapeutic interventions for previously untreatable genetic diseases.

Key Molecular Targets and Associated Disease Pathways

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) represent a transformative class of therapeutic agents that modulate gene expression through precise Watson-Crick base pairing with target RNA sequences [23]. These synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules, typically 15-22 nucleotides in length, offer researchers and drug developers a powerful tool for investigating disease pathways and developing targeted treatments for conditions with high unmet medical need [27]. The fundamental mechanism involves ASOs binding to complementary RNA sequences, leading to gene silencing through RNase H-mediated degradation of the target RNA or through steric blockade of translation or splicing mechanisms [23]. This application note details key molecular targets, their associated disease pathways, and provides structured experimental protocols for ASO-based research.

Key Molecular Targets and Clinical Applications

ASO technology has enabled targeting of previously "undruggable" genetic pathways, particularly for rare genetic, neuromuscular, and neurodegenerative disorders [28]. The table below summarizes prominent molecular targets in ASO research and development:

Table 1: Key Molecular Targets for ASO Therapeutics

| Molecular Target | Associated Disease(s) | ASO Mechanism | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dystrophin gene | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) | Exon skipping (e.g., exon 53 skipping) to restore reading frame [28] | Clinical (WVE-N531 in development) [28] |

| Apolipoprotein(a) | Hyperlipoproteinaemia | Reduce apolipoprotein(a) production [28] | Phase III (Pelacarsen) [28] |

| SMN2 gene | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | Splicing modulation to increase functional SMN protein [23] | Approved therapies |

| SCN2A gene | Developmental epileptic encephalopathy, channelopathies | Variant-specific suppression for seizure control [29] | Clinical trials |

| miR-122 | Hepatitis C, cancer | Inhibition of miRNA function [23] | Research/Preclinical |

| UCA1 | Various cancers | Targeting long non-coding RNA [30] | Research |

| Huntington's disease gene | Huntington's disease | Reduce mutant protein production [31] | Pipeline |

| Hereditary transthyretin (TTR) | hATTR Amyloidosis | Reduce mutant TTR production [31] | Approved therapies |

The global ASO market, valued at approximately $2.5 billion in 2025, reflects substantial investment in these targets, with anticipated growth of 15% CAGR through 2035 [31]. Current pipelines include over 170 therapeutic candidates being developed by more than 30 companies, highlighting the robust interest in this modality [31].

ASO Mechanisms of Action

ASOs employ distinct mechanisms to modulate gene expression, with the primary pathways being RNase H-mediated degradation and steric blockade:

Diagram 1: ASO Mechanisms of Action

The RNase H pathway requires a central DNA "gap" region within the ASO to form DNA-RNA heteroduplexes that recruit endogenous RNase H enzymes, leading to catalytic cleavage of the target RNA [23]. Steric-blocking ASOs, typically fully modified with high-affinity nucleotides, physically prevent cellular machinery from accessing specific RNA regions without degradation, enabling precise modulation of splicing patterns or translation initiation [23].

Chemical Modifications and Design Strategies

Optimizing ASO efficacy requires strategic chemical modifications to enhance stability, binding affinity, and cellular delivery:

Table 2: Key Chemical Modifications for ASOs

| Modification Type | Common Examples | Key Properties | Impact on RNase H Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone | Phosphorothioate (PS) | Improved nuclease resistance, protein binding, bioavailability [23] [27] | Maintains activity |

| Sugar (2'-position) | 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) | Increased binding affinity, nuclease resistance [23] | Eliminates activity |

| Conformationally restricted | Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA/BNA) | Significantly increased binding affinity, nuclease resistance [23] | Eliminates activity |

| Base | 5-Methylcytosine | Increased Tm, reduced immune activation in CpG motifs [27] | Maintains activity |

Modern ASO design typically employs gapmer architectures: chimeric oligonucleotides with 2-5 modified nucleotides (e.g., LNA or 2'-MOE) on each terminus flanking a central 8-10 base DNA "gap" [23]. The modified wings enhance nuclease resistance and target affinity, while the DNA gap permits RNase H recruitment. Comparative studies demonstrate that LNA-containing gapmers show superior potency compared to 2'-MOE and 2'-OMe modifications [27].

Experimental Protocol: ASO-Mediated Gene Silencing

Protocol 1: In Vitro Screening of ASO Efficacy

Objective: Evaluate ASO-mediated knockdown of target gene expression in cell culture.

Materials:

- Synthetic ASOs (desalted or HPLC-purified)

- Appropriate cell line expressing target gene

- Transfection reagent compatible with oligonucleotides

- RT-qPCR reagents for mRNA quantification

- Western blot reagents for protein quantification

Procedure:

- ASO Design: Design 3-5 ASOs targeting different regions of the target mRNA. Include appropriate control ASOs (mismatch and scrambled sequences) [30].

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in 24-well plates at 50-70% confluence 24 hours before transfection.

- Transfection Complex Formation:

- Dilute ASOs in serum-free medium to 2x final concentration

- Dilute transfection reagent separately in serum-free medium

- Combine diluted ASO and transfection reagent, incubate 15-20 minutes

- Treatment: Add complexes to cells at multiple concentrations (e.g., 10-100 nM) in triplicate.

- Incubation: Culture cells for 24-48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Analysis:

- Harvest cells for RNA isolation and RT-qPCR analysis of target mRNA levels

- Perform western blotting to assess protein level reduction

- Include appropriate housekeeping genes for normalization [30]

Validation:

- Employ at least two independent ASOs targeting different regions of the same gene

- Include mismatch controls (≥4 base mismatches) and scrambled sequence controls

- Establish dose-response curves to calculate IC₅₀ values [30]

Protocol 2: Animal Studies for ASO Efficacy

Objective: Evaluate ASO-mediated gene silencing in vivo.

Materials:

- PS-modified ASOs (HPLC-purified with Na⁺ salt exchange)

- Sterile saline for formulation

- Appropriate animal model

- Syringes/administration equipment

Procedure:

- ASO Preparation: Dissolve ASOs in sterile saline. For in vivo use, higher purity oligos are required [27].

- Dosing Regimen:

- Determine appropriate route of administration (subcutaneous, intravenous, intrathecal)

- Establish multiple dosage levels based on preliminary studies

- Include appropriate vehicle control groups

- Administration: Administer ASOs according to established schedule.

- Monitoring: Observe animals for signs of toxicity or adverse effects.

- Tissue Collection: Harvest relevant tissues at predetermined timepoints.

- Analysis:

- Quantify target mRNA reduction in tissues using RT-qPCR

- Assess protein level modulation by western blot or immunohistochemistry

- Evaluate phenotypic improvements using disease-relevant endpoints

Considerations:

- Parenteral administration (particularly subcutaneous and intravenous) predominates in clinical settings [31]

- Tissue distribution varies with ASO chemistry and administration route

- Long-term studies require careful monitoring of potential toxicities

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASO Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| ASO Chemistry Types | Phosphorothioate backbone, 2'-MOE, LNA, 2'-OMe | Enhance stability, binding affinity, and cellular uptake [23] [27] |

| Control Oligos | Mismatch control (≥4 base mismatches), scrambled sequence | Distinguish sequence-specific from non-specific effects [30] |

| Delivery Reagents | Cationic lipids, polymer-based transfection reagents | Facilitate cellular uptake of ASOs in vitro |

| Purification Methods | HPLC purification, standard desalt | Ensure oligo quality and reduce toxicity (essential for in vivo studies) [27] |

| Detection Assays | RT-qPCR reagents, northern blot, western blot | Quantify mRNA and protein level changes post-treatment [30] |

Experimental Workflow

A comprehensive ASO experimental program incorporates sequential validation steps:

Diagram 2: ASO Experimental Workflow

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

ASO technology continues to expand into novel therapeutic areas. Splice-switching ASOs represent a promising application, with demonstrated success in modulating splicing of the dystrophin gene in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy to produce partially functional protein isoforms [23]. Additionally, ASOs targeting non-coding RNAs—particularly microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs—offer opportunities to modulate complex regulatory networks in oncology and other disease areas [23] [30].

The emergence of individualized ASO therapies for ultra-rare diseases (affecting single patients or small families) represents a frontier in precision medicine. Organizations like the 1 Mutation 1 Medicine (1M1M) consortium are establishing frameworks for developing patient-specific ASOs for neurological diseases, demonstrating meaningful clinical benefits even in severe, progressive disorders [29] [32].

Antisense oligonucleotides provide researchers and drug developers with a versatile platform for targeted gene modulation across diverse disease pathways. The continued refinement of ASO chemistry, design principles, and delivery strategies is accelerating the translation of this technology from basic research to clinical applications. By adhering to rigorous experimental standards—including appropriate controls, dose-response assessments, and orthogonal validation methods—scientists can reliably exploit ASO technology to investigate disease mechanisms and develop novel therapeutic interventions for conditions with significant unmet medical needs.

From Bench to Bedside: Designing, Developing, and Deploying ASO Therapeutics

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are short, synthetic nucleic acid strands designed to modulate gene expression by binding to specific RNA targets through Watson-Crick base pairing [21] [3]. Their therapeutic success fundamentally relies on chemical modifications that enhance native oligonucleotide properties, conferring resistance to nucleases, improving target affinity, and optimizing pharmacokinetic profiles [33] [34]. First-generation ASOs primarily utilized phosphorothioate (PS) backbone modifications, while subsequent generations introduced sophisticated sugar modifications including 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), and phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMO), alongside conformationally constrained nucleotides like Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) [33] [35]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these key chemical modifications and detailed protocols for their application in gene silencing research, supporting a broader thesis on ASO therapeutic development.

Key Chemical Modifications and Properties

Table 1: Comparative properties of major ASO chemical modifications.

| Modification Type | Key Structural Feature | Mechanism Compatibility | Thermal Stability (ΔTm/mod) | Nuclease Resistance | Reported Toxicity Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS Backbone | Sulfur substitutes non-bridging oxygen | RNase H, Steric Block | Slight decrease | High | Dose-dependent; reduced vs. early generations [33] |

| 2'-OMe | 2'-O-methyl group on ribose | Steric Block only | +0.9 to +1.6°C | High | Favorable safety profile [35] |

| 2'-MOE | 2'-O-methoxyethyl group on ribose | Steric Block only | +0.9 to +1.6°C | Very High | Reduced pro-inflammatory effects [35] |

| PMO | Morpholino ring & phosphorodiamidate | Steric Block only | Similar to DNA | Very High | Unmodified PMO: Low; ivPMO-conjugates: Higher toxicity reported [36] |

| LNA | 2'-O, 4'-C methylene bridge | RNase H (in gapmers) | +4 to +8°C | Very High | Hepatotoxicity at high doses; sequence-dependent [33] |

Mechanism-Based Classification

Table 2: Guidance on modification selection based on desired mechanism of action.

| Mechanism of Action | Recommended Modification Patterns | Example ASO Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| RNase H-mediated Knockdown | Gapmer design: Central DNA/PS gap with modified flanks (2'-MOE, LNA) | Mipomersen (2'-MOE), Inotersen (2'-MOE) [35] [12] |

| Splice Switching / Steric Block | Uniform modification (2'-MOE, 2'-OMe, PMO) | Nusinersen (2'-MOE), Eteplirsen (PMO) [35] |

| siRNA (RISC-mediated) | Selective 2' modifications on sense/antisense strands | (Investigational, 2'-MOE shows promise) [35] |

Experimental Protocols for ASO Evaluation

Protocol: In Vitro Splicing Modulation Assay

Objective: Evaluate the efficacy of differently modified ASOs to modulate pre-mRNA splicing in cell culture [36].

Materials:

- Splice Reporter Vector (Midigene): Plasmid containing genomic region of target gene with splice sites of interest [36].

- Cell Line: Appropriate mammalian cells (e.g., HEK-293T, mIMCD3) [36].

- Transfection Reagent: Lipid-based (e.g., FuGENE HD) for 2'-OMe/2'-MOE/PS; Scraping method for PMOs [36].

- ASOs: Sequence-matched ASOs with different chemical modifications (2'-OMe/PS, 2'-MOE/PS, PMO) and scrambled control oligonucleotide (SON) [36].

- RNA Isolation & RT-PCR Kit: For analyzing splicing patterns.

Procedure:

- Day 1: Cell Seeding: Seed ~300,000–400,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate.

- Day 2: Midigene Transfection: Transfect 1.2 µg midigene using FuGENE HD at 3:1 reagent:DNA ratio in Opti-MEM.

- Day 3: Cell Splitting: Split transfected cells 1:6 into 12-well plates.

- Day 3: ASO Transfection:

- For 2'-OMe/PS and 2'-MOE/PS: Transfect at 0.5 µM final concentration using FuGENE HD.

- For PMOs: Use 2.5 µM final concentration in fresh medium; remove old medium, add PMO-containing medium, and gently detach cells by scraping to facilitate uptake [36].

- Day 5: Harvest and Analysis: Collect cells 48 hours post-ASO transfection.

- Isolate total RNA.

- Perform RT-PCR across the spliced region of interest.

- Analyze PCR products by gel electrophoresis or capillary electrophoresis to quantify splicing changes (e.g., exon skipping or inclusion).

Protocol: In Vivo Efficacy and Toxicity Assessment

Objective: Determine the efficacy and safety profile of modified ASOs in an animal model [36] [37].

Materials:

- Animals: Wild-type mice (e.g., C57BL/6J).

- ASOs: Chemically modified ASOs in sterile saline.

- Delivery Equipment: Micropipettes for intracerebroventricular (ICV) or intravitreal injection.

- Behavioral Analysis System: Open field test apparatus.

- Histology Reagents: Fixatives, stains for morphological analysis.

Procedure:

- ASO Administration:

- Efficacy Assessment:

- After a predetermined period (e.g., 2-4 weeks), sacrifice animals and harvest target tissues.

- Isolate RNA and protein from tissues.

- Quantify target gene expression using qRT-PCR (for RNA knockdown) or western blot (for protein reduction).

- For splice-switching ASOs, analyze RNA by RT-PCR to detect splicing modifications.

- Toxicity Assessment:

- Clinical Observation: Monitor animals externally for phenotypic changes (e.g., ocular abnormalities) [36].

- Behavioral Testing: Perform open field tests to assess acute neurotoxicity, such as changes in locomotor activity [37].

- Histological Analysis: Fix tissues, section, and stain (e.g., H&E) to evaluate morphological alterations and cellular integrity [36].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

ASO Mechanisms of Action Pathway

Diagram Title: Primary ASO Mechanisms of Action

In Vitro to In Vivo Screening Workflow

Diagram Title: ASO Screening Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and resources for ASO research.

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Suppliers / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2'-MOE-modified ASOs | Steric-blocking splice-switching ASOs; high stability & affinity | ProQR Therapeutics [36] |

| PMO Oligonucleotides | Steric-blocking applications; uncharged backbone | Gene Tools, LLC [36] |

| LNA-modified ASOs | High-affinity gapmers for potent knockdown | Exiqon, Qiagen; monitor for hepatotoxicity [33] |

| PS Backbone Reagents | Phosphoramidites for nuclease-resistant synthesis | Glen Research, ChemGenes |

| Splice Reporter Vectors | Midigene constructs for splicing assays | Custom generation via Gateway Cloning [36] |

| FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent | Lipid-based delivery of charged ASOs (2'-OMe/PS, 2'-MOE/PS) | Promega [36] |

| Scraping Method | Mechanical delivery for uncharged PMOs | Alternative to transfection reagents [36] |

The strategic selection and application of chemical modifications—including PS, PMO, LNA, and 2' modifications—are fundamental to developing ASOs with optimal efficacy and safety profiles. The protocols and comparative data provided here offer a framework for systematic evaluation of these modifications in both in vitro and in vivo settings. As the field advances, continued refinement of chemical architectures and delivery methods will expand the therapeutic potential of ASOs to target tissues beyond the liver and central nervous system, addressing an increasingly broad range of genetic disorders.

The therapeutic potential of Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) and other nucleic acid therapeutics is often hampered by significant delivery challenges that must be overcome to achieve clinical efficacy. These macromolecules face numerous physiological barriers including nuclease-mediated degradation, renal clearance, inefficient cellular uptake, and entrapment within endolysosomal compartments [38] [39]. Due to their inherent properties—including high molecular weight, negative charge, and hydrophilicity—naked oligonucleotides struggle to cross biological membranes and reach their intracellular sites of action [39] [40].

To address these limitations, two primary delivery strategies have emerged: liposomal encapsulation and biomolecular conjugation. These approaches enhance the stability, bioavailability, and targeted delivery of ASOs, thereby improving their therapeutic index and expanding their potential applications in gene silencing research [38] [41]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these platforms and detailed protocols for their evaluation in preclinical research settings.

Liposomal Delivery Systems

Liposomes are spherical vesicles composed of phospholipid bilayers that can encapsulate nucleic acids, protecting them from degradation and facilitating cellular uptake. Advanced liposomal formulations, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), have become a cornerstone for systemic delivery of RNA therapeutics [38] [42]. These systems excel at encapsulating large nucleic acid payloads and can be engineered with targeting ligands for tissue-specific delivery. The first FDA-approved siRNA therapeutic, patisiran, utilizes a nanoparticle delivery system, demonstrating the clinical validity of this approach [11].

Biomolecular Conjugation Strategies

Conjugation involves the covalent attachment of biomolecules directly to oligonucleotides to enhance their pharmacokinetic properties and cellular uptake. This strategy typically results in smaller, more defined molecular entities compared to nanoparticle systems. Common conjugates include GalNAc for hepatocyte targeting, lipids for membrane interaction and improved biodistribution, and antibodies for cell-specific targeting [8] [41] [43].

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Delivery Platforms

| Feature | Liposomal/Nanoparticle Systems | Biomolecular Conjugates |

|---|---|---|

| Size Range | 50-200 nm | Molecular (5-15 nm) |

| Typical Payload | Multiple oligonucleotides per particle | Single oligonucleotide per conjugate |

| Targeting Mechanism | Surface-functionalized with ligands | Direct ligand-receptor interaction |

| Manufacturing Complexity | High (multi-component assembly) | Medium (chemical conjugation) |

| Clinical Examples | Patisiran (LNP) | Givosiran (GalNAc-siRNA), Inclisiran (GalNAc-siRNA) |

| Primary Applications | Systemic delivery, large payloads | Targeted organ delivery (e.g., liver) |

Quantitative Analysis of Conjugation Efficacy

Recent comparative studies have provided quantitative data on the efficacy of various conjugation strategies for ASO delivery. A 2025 study systematically evaluated aptamer, vitamin E, and cholesterol conjugates of the ASO PNAT524 for cellular uptake and exon-skipping activity in cancer cell models [41]. The results demonstrated significant differences in performance between conjugation approaches.

Table 2: Efficacy Comparison of ASO Conjugation Strategies

| Conjugation Type | Exon-Skipping Efficiency | Cellular Uptake | Cytotoxic Effects | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconjugated ASO | Low (baseline) | Low | Minimal | Requires transfection reagent for internalization |

| Aptamer (AS1411) | Not significant | Moderate | Minimal | Target-specific (nucleolin); limited efficacy enhancement |

| Aptamer (S2.2) | Not significant | Moderate | Minimal | Target-specific (MUC1); limited efficacy enhancement |

| Vitamin E | High, dose-dependent | High | Potent | Natural lipid; uptake via lipoprotein receptors |

| Cholesterol | Highest, dose-dependent | Highest | Most potent | Enhanced cellular uptake via LDL receptor; superior efficacy |

The cholesterol-conjugated ASO (524-Chol) demonstrated the highest efficacy in splice-modulating activity and cytotoxic outcomes, establishing cholesterol conjugation as a particularly promising strategy for enhancing ASO delivery in cancer therapeutic applications [41].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Cholesterol-ASO Conjugates

Conjugate Synthesis and Characterization

Materials:

- PNAT524 ASO (2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate backbone)

- Cholesterol-NHS ester or cholesterol-thiol reagents

- C6 thiol linker or triethylene glycol (TEG) linker

- Purification equipment (HPLC)

- Characterization instruments (LC-MS, MALDI-TOF)

Methodology:

- Conjugation Chemistry: Conjugate cholesterol to the 5' end of PNAT524 using a thiol linker (e.g., C6 thiol) to create 524-S-S-Chol [41].

- Purification: Purify the conjugate using reverse-phase HPLC to remove unreacted components.

- Quality Control: Verify conjugate identity and purity using LC-MS. Ensure >95% purity for cellular assays.

- Storage: Prepare stock solutions in nuclease-free water or DMSO and store at -20°C.

Cellular Uptake and Efficacy Assessment

Materials:

- Cancer cell lines relevant to research goals (e.g., HeLa, A549)

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filters

- qRT-PCR equipment and reagents

- Cell viability assay kits (MTT, CCK-8)

- Serum-free cell culture media

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells in 24-well plates at 5×10⁴ cells/well and culture for 24 hours.

- Treatment Application:

- Prepare serial dilutions of cholesterol-ASO conjugates in serum-free medium (e.g., 10 nM to 1 μM).

- Apply treatments to cells and incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Include untransfected ASO controls and vehicle controls.

- Uptake Analysis:

- For fluorescently labeled ASOs, fix cells after treatment and image using fluorescence microscopy.

- Quantify fluorescence intensity using image analysis software.

- Functional Assessment:

- Extract total RNA and perform qRT-PCR to measure target mRNA levels.

- Analyze exon-skipping efficiency using RT-PCR with flanking primers.

- Viability Assessment:

- Perform cell viability assays (e.g., MTT) according to manufacturer protocols.

- Calculate IC₅₀ values for cytotoxic effects.

Intracellular Trafficking and Mechanism of Action

Understanding the cellular fate of delivered ASOs is crucial for optimizing delivery strategies. Both liposomal and conjugate-based systems must overcome the endosomal barrier to release ASOs into the cytoplasm and allow translocation to the nucleus for certain mechanisms of action.

Key Mechanisms:

- Liposomal Systems: Employ pH-sensitive or fusogenic lipids that disrupt endosomal membranes through the proton sponge effect or membrane fusion [38] [42].

- Cholesterol Conjugates: Enhance uptake through LDL receptor-mediated endocytosis and may promote endosomal escape through hydrophobic interactions with membranes [41].

- GalNAc Conjugates: Utilize the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) on hepatocytes for highly efficient receptor-mediated endocytosis [8] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for ASO Delivery Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Research Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles | Ionizable lipids (DLin-MC3-DMA), Phospholipids, Cholesterol, PEG-lipids | ASO encapsulation and protection; enhances cellular uptake and biodistribution | Optimal N:P ratio critical for efficiency; PEG content affects circulation time |

| Conjugation Ligands | GalNAc, Cholesterol, Vitamin E (α-tocopherol), Antibodies | Targeted delivery; improved cellular uptake and pharmacokinetics | Linker choice (TEG, C6 thiol) affects release and activity |

| Chemical Modifications | Phosphorothioate (PS), 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) | Enhanced nuclease resistance; improved binding affinity; reduced immunogenicity | LNA modifications require careful design to minimize hepatotoxicity |

| Cell Lines | HepG2 (hepatocytes), HeLa (epithelial), patient-derived organoids | In vitro modeling of ASO uptake and activity | Primary cells or 3D models may better recapitulate in vivo conditions |

| Analytical Tools | LC-MS/MS, fluorescence microscopy, qRT-PCR, flow cytometry | Quantification of ASO uptake, distribution, and functional activity | LC-MS/MS offers specificity for parent vs. metabolite differentiation |

Protocol for Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation and Testing

Microfluidic LNP Preparation

Materials:

- Ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA)

- Helper lipids (DSPC, cholesterol)

- PEG-lipid (DMG-PEG2000)

- ASO in citrate buffer (pH 4.0)

- Ethanol (100%)

- Microfluidic device (NanoAssemblr, staggered herringbone mixer)

Methodology:

- Lipid Solution Preparation: Dissolve ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol at specific molar ratios (50:10:38.5:1.5).

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dilute ASO in citrate buffer (pH 4.0) to 0.2 mg/mL.

- Mixing Procedure:

- Set total flow rate to 12 mL/min with aqueous:organic flow rate ratio of 3:1.

- Use microfluidic device to rapidly mix aqueous and organic phases.

- Collect resulting LNP suspension.

- Dialyze against PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 hours to remove ethanol.

- Characterize particle size (Zetasizer), polydispersity index, encapsulation efficiency (RiboGreen assay).

In Vivo Biodistribution Study

Materials:

- Fluorescently labeled ASO (Cy5, Cy7)

- Animal model (mice, rats)

- IVIS imaging system

- Tissue homogenization equipment

Methodology:

- Dose Administration: Inject fluorescent ASO-LNPs via tail vein (dose: 1-5 mg ASO/kg).

- Time Points: Image animals at 1, 4, 24, and 48 hours post-injection.

- Ex Vivo Analysis:

- Euthanize animals at endpoint.

- Collect tissues (liver, spleen, kidney, lung).

- Image excised tissues using IVIS.

- Homogenize tissues and quantify ASO content using LC-MS/MS or fluorescence measurement.

- Data Analysis: Calculate percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).