A Comprehensive Guide to Validating CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Efficiency: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Genomic Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency in genomic DNA.

A Comprehensive Guide to Validating CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Efficiency: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Genomic Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency in genomic DNA. It covers the foundational principles of CRISPR mechanics and DNA repair pathways, explores methodological approaches for introducing edits and designing templates, details strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing efficiency while minimizing off-target effects, and outlines rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design robust, reproducible, and clinically relevant CRISPR validation workflows.

Understanding the CRISPR/Cas9 Engine: Mechanisms and Key Factors Governing Editing Success

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized genomic DNA research by providing an unprecedented ability to perform targeted genome editing. This technology's core consists of three essential components that function as an integrated molecular machine: the guide RNA (gRNA), which provides sequence specificity; the Cas nuclease, an enzyme that acts as the molecular scissor to cut DNA; and the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence that is critical for target recognition [1] [2]. The precise interplay between these components enables researchers to induce double-strand breaks at predetermined locations in the genome, facilitating gene knockouts, insertions, and corrections. As CRISPR technology advances into clinical applications, with the recent FDA approval of the first CRISPR/Cas9-based gene therapy, understanding the function, optimization, and limitations of each component becomes increasingly crucial for validating editing efficiency and ensuring experimental success [3] [4].

Component Deep Dive: Structure, Function, and Experimental Considerations

Guide RNA (gRNA): The Targeting System

The guide RNA serves as the targeting mechanism of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, directing the Cas nuclease to a specific genomic locus through Watson-Crick base pairing. Structurally, the gRNA is a chimeric single guide RNA (sgRNA) that combines two natural RNA elements: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which contains a 20-nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target DNA, and the trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 protein [2] [4]. This synthetic fusion simplifies the system to a two-component setup while maintaining full functionality.

The targeting specificity of the gRNA is determined by the 20-nucleotide spacer sequence, which must be carefully designed to minimize off-target effects while maintaining high on-target efficiency. Critical considerations for gRNA design include:

- Seed Sequence: The 10-12 nucleotides proximal to the PAM are crucial for target recognition and binding stability [5].

- Specificity: The spacer sequence should be unique within the genome to avoid off-target editing at similar sequences.

- GC Content: An optimal GC content (40-60%) improves gRNA stability and binding efficiency.

- Secondary Structure: Potential hairpin formations in the gRNA can interfere with Cas9 binding and should be minimized [2].

In experimental practice, gRNAs are typically encoded in plasmid vectors under the control of RNA polymerase III promoters such as U6, ensuring high expression levels in mammalian cells [2].

Cas Nuclease: The Molecular Scissor

The Cas nuclease is the effector protein that executes the DNA cleavage function. The most widely used variant, derived from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), contains two catalytic domains: the HNH domain, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA, and the RuvC domain, which cleaves the non-complementary strand [4]. This results in a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [1].

Cas9 undergoes a conformational activation process upon gRNA binding, transitioning from an inactive to an active state capable of DNA interrogation. The mechanism involves:

- PAM Scanning: Cas9 first searches for compatible PAM sequences through three-dimensional diffusion along the DNA [1].

- DNA Melting: Upon PAM recognition, Cas9 unwinds the adjacent DNA duplex.

- Target Verification: The gRNA interrogates the unwound DNA for complementarity.

- Conformational Activation: Full complementarity triggers nuclease activity [4].

The discovery and engineering of novel Cas variants with diverse properties have significantly expanded the CRISPR toolkit. Table 1 compares commonly used Cas nucleases and their characteristics, highlighting the importance of selecting the appropriate nuclease for specific experimental requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Commonly Used Cas Nuclease Variants

| Nuclease | Origin | Size (aa) | PAM Sequence | Editing Efficiency | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 1,368 | NGG | High | Standard gene editing, knockout generation |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | 1,053 | NNGRRT | Moderate | In vivo applications with AAV delivery |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | 1,082 | NNNNGATT | Moderate | Applications requiring high specificity |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | 984 | NNNNRYAC | Moderate | Compact nuclease for viral delivery |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | 1,300 | TTTV | High | Multiplexed editing, staggered cuts |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered | ~1,300 | TN and/or TNN | High | Reduced off-target effects |

| OpenCRISPR-1 | AI-designed | N/A | NGG | Comparable/Improved vs. SpCas9 | High-fidelity editing [6] |

PAM Sequence: The Recognition Signal

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) located immediately downstream of the target DNA region. This motif is not part of the gRNA recognition sequence but is essential for Cas nuclease activation [1] [7]. For the commonly used SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide base [1] [7].

The PAM serves two critical biological functions:

- Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination: In bacterial immune systems, the absence of PAM sequences in the host's CRISPR array prevents autoimmunity, ensuring that Cas9 only targets foreign DNA [1].

- Cas9 Activation: PAM binding triggers conformational changes in Cas9 that facilitate DNA unwinding and enable gRNA-DNA hybridization [7].

The PAM requirement represents a fundamental constraint in CRISPR experimental design, as it determines the potential target sites within a genome. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of PAM sequences for various Cas nucleases, highlighting the expanding targeting range through nuclease engineering.

Table 2: PAM Sequences and Recognition Patterns for Cas Nuclease Variants

| CRISPR Nucleases | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| StCas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | NNAGAAW |

| LbCpf1 (Cas12a) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| AsCpf1 (Cas12a) | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

| BhCas12b v4 | Bacillus hisashii | ATTN, TTTN and GTTN |

| Cas14 | Uncultivated archaea | T-rich PAM sequences, eg. TTTA for dsDNA cleavage |

| Cas3 | in silico analysis of various prokaryotic genomes | No PAM sequence requirement |

Recent advances have significantly expanded PAM flexibility through protein engineering approaches such as:

- Directed Evolution: Creating Cas9 mutants with altered PAM specificities (e.g., xCas9, SpCas9-NG) [1].

- Structure-Guided Engineering: Modifying PAM-interacting domains to recognize alternative sequences.

- AI-Assisted Design: Using large language models to generate novel editors with tailored PAM preferences, as demonstrated by OpenCRISPR-1 [6].

Experimental Validation: Assessing CRISPR Component Performance

Protocol for Validating Editing Efficiency in Genomic DNA

To establish a robust framework for evaluating CRISPR/Cas9 component performance, we outline a standardized protocol adapted from successful genome editing studies in eukaryotic systems [8]:

1. Target Selection and gRNA Design:

- Identify target sites within the gene of interest containing appropriate PAM sequences.

- Design multiple gRNAs (typically 3-5) targeting different regions to account for variability in efficiency.

- Evaluate potential off-target sites using bioinformatic tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder) and select gRNAs with minimal predicted off-target activity.

2. Plasmid Construction:

- Clone selected gRNA sequences into a CRISPR expression vector containing the U6 promoter.

- Select an appropriate Cas9 expression vector (e.g., with CMV promoter for mammalian cells).

- For transfection efficiency monitoring, include a fluorescent marker (e.g., GFP) or antibiotic resistance gene.

3. Cell Transfection and Delivery:

- Culture appropriate cell lines (HEK293T is commonly used for initial validation).

- Transfect using preferred method (lipofection, electroporation) with 1:3 mass ratio of Cas9:gRNA plasmids.

- Include untransfected and vector-only controls.

4. Editing Efficiency Analysis (72-96 hours post-transfection):

- Harvest genomic DNA using standard extraction protocols.

- Amplify target region by PCR (amplicon size: 400-800 bp).

- Quantify editing efficiency using T7 Endonuclease I assay or tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) analysis.

- For precise quantification, perform next-generation sequencing of amplicons.

5. Off-Target Assessment:

- Analyze top 5-10 predicted off-target sites by PCR and sequencing.

- Alternatively, use genome-wide methods like GUIDE-seq for comprehensive off-target profiling.

This protocol enables systematic comparison of different gRNA designs, Cas nuclease variants, and their combinations, providing quantitative data on editing efficiency and specificity.

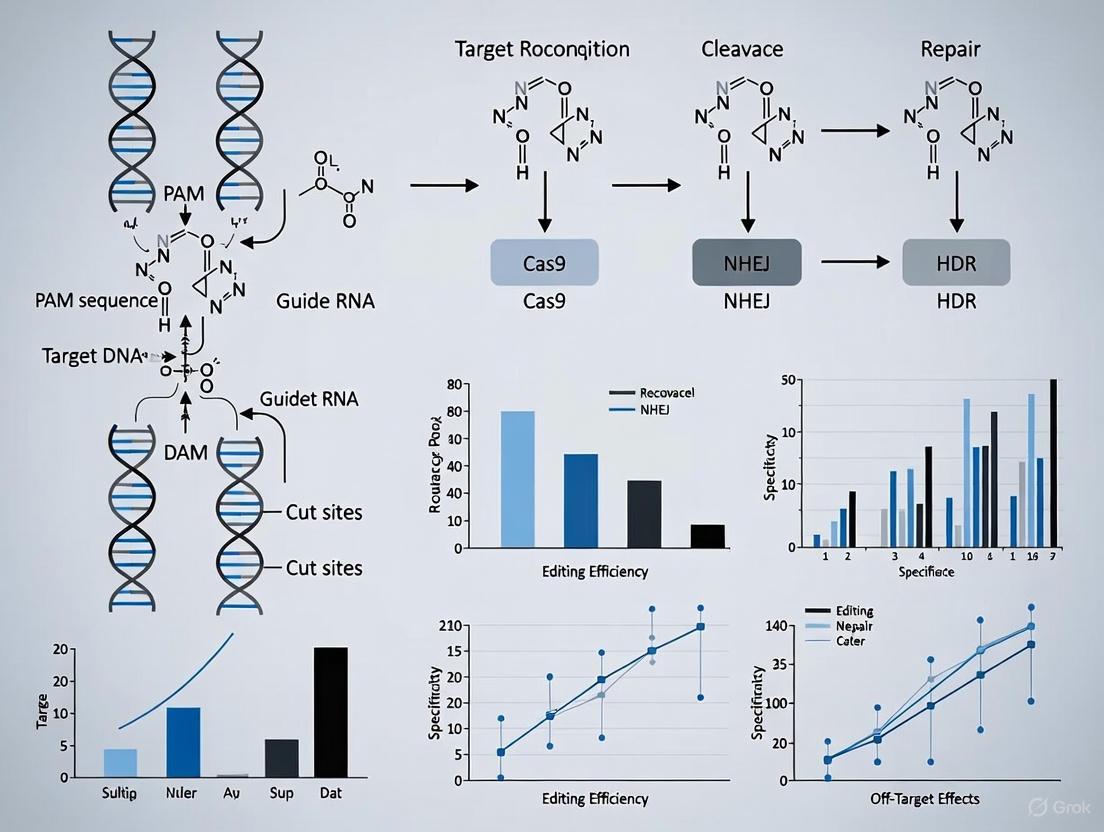

Workflow Visualization: Experimental Process for CRISPR Validation

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in the experimental validation of CRISPR/Cas9 components:

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Efficiency Across Systems

Recent advances in CRISPR technology have yielded numerous engineered systems with varied performance characteristics. Table 3 summarizes quantitative efficiency data for different CRISPR systems, providing a reference for selecting appropriate components based on experimental needs.

Table 3: Editing Efficiency Metrics for CRISPR Systems in Genomic DNA Research

| CRISPR System | Average On-Target Efficiency | Relative Off-Target Rate | Optimal Cell Types | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (WT) | 40-60% | Baseline | Mammalian cells, plants | Reliable, well-characterized |

| High-Fidelity SpCas9 | 30-50% | 2-5x lower than WT | All cell types | Reduced off-target effects |

| SaCas9 | 20-40% | Comparable to SpCas9 | Neuronal cells, in vivo applications | Compact size for AAV delivery |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | 25-45% | 2-4x lower than SpCas9 | Mammalian cells, plants | Staggered cuts, simpler gRNA |

| Base Editors | 15-50% (varies by type) | 10-100x lower than nuclease | Non-dividing cells | No double-strand breaks, precise base changes |

| Prime Editors | 10-30% | Extremely low | All cell types | Versatile, all possible base changes |

| CAST Systems (I-F) | Up to 100% in prokaryotes | Minimal (no DSBs) | Prokaryotes, early development in eukaryotes | Large DNA insertions without DSBs |

| AI-Designed Editors (OpenCRISPR-1) | Comparable/Improved vs. SpCas9 | Improved specificity | Human cells | Novel sequences, optimized properties [6] |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Emerging Technologies

Specialized CRISPR Systems for Advanced Genome Engineering

Beyond standard gene editing, specialized CRISPR systems have been developed to address specific research needs:

CRISPR-Associated Transposase (CAST) Systems: CAST systems represent a breakthrough for large DNA insertions without creating double-strand breaks. The type I-F CAST system has demonstrated nearly 100% insertion efficiency in E. coli with donor sequences up to 15.4 kb, while type V-K variants can accommodate inserts up to 30 kb [9]. Although current editing efficiency in mammalian cells remains low (approximately 1-3%), ongoing engineering efforts show promise for future applications [9].

Base and Prime Editing: These precision editing systems enable specific nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks. Base editors directly convert one DNA base to another (C→T, A→G) using catalytically impaired Cas proteins fused to deaminase enzymes, achieving efficiencies of 15-50% with dramatically reduced off-target effects [4]. Prime editors offer even greater versatility, supporting all 12 possible base-to-base conversions with minimal indels, though at lower efficiencies (10-30%) [4].

Anti-CRISPR Systems for Enhanced Control: Recent developments in anti-CRISPR proteins provide temporal control over Cas9 activity, addressing safety concerns related to prolonged nuclease expression. The LFN-Acr/PA system, derived from anthrax toxin components, enables rapid shutdown of Cas9 activity within minutes of application, reducing off-target effects and improving editing specificity by up to 40% [3].

Mechanism Visualization: CRISPR-Cas9 Molecular Machinery

The molecular mechanism of CRISPR/Cas9 can be visualized as follows:

Integration with Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The application of artificial intelligence and machine learning represents the cutting edge of CRISPR technology development. Large language models (LMs) trained on biological diversity at scale have demonstrated remarkable success in designing novel gene editors. Recently, researchers curated a dataset of over 1 million CRISPR operons through systematic mining of 26 terabases of assembled genomes and metagenomes, using this information to fine-tune protein language models [6]. This approach generated 4.8 times the number of protein clusters across CRISPR-Cas families found in nature, with AI-designed editors like OpenCRISPR-1 showing comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9, despite being 400 mutations away in sequence [6].

Machine learning tools are also being deployed to predict gRNA efficiency and off-target effects with increasing accuracy. As more sequence features are identified and incorporated into deep learning tools, predictions are expected to better align with experimental results, streamlining the CRISPR design process [10]. These computational approaches leverage large CRISPR databases to identify patterns and relationships that would be difficult to discern through manual analysis alone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful validation of CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency requires access to specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogs essential research solutions for CRISPR experimentation:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for CRISPR/Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vectors | Delivery of Cas nuclease | CMV or CAG promoters, nuclear localization signals, codon optimization for target species |

| gRNA Cloning Vectors | gRNA expression | U6 or H1 promoters, BsaI/BbsI restriction sites for golden gate assembly |

| Bioinformatic Tools | gRNA design and off-target prediction | CATS [5], Cas-OFFinder, CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR |

| Validation Enzymes | Editing efficiency quantification | T7 Endonuclease I, Surveyor Nuclease |

| Delivery Reagents | Introduction of CRISPR components | Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX, electroporation systems (Neon, Amaxa) |

| Cell Lines | Editing validation | HEK293T (high transfection efficiency), target cell lines relevant to research |

| Control Plasmids | Experimental standardization | Non-targeting gRNA, GFP reporter constructs |

| Sequencing Primers | Amplification of target loci | Custom-designed for each target site, flanking edited region |

| Anti-CRISPR Proteins | Control of editing duration | LFN-Acr/PA system for rapid Cas9 inhibition [3] |

| HDR Donor Templates | Precise gene editing | Single-stranded or double-stranded DNA templates with homology arms |

The CATS (Comparing Cas9 Activities by Target Superimposition) bioinformatic tool deserves special mention, as it automates the detection of overlapping PAM sequences across different Cas9 nucleases and identifies allele-specific targets, particularly those arising from pathogenic mutations [5]. This tool significantly reduces the time and effort required for CRISPR/Cas9 experimental design by enabling direct comparison of nucleases with different PAM requirements in the same genomic context.

The core components of the CRISPR/Cas9 system—gRNA, Cas nuclease, and PAM sequence—function as an integrated molecular machine that can be strategically optimized for specific research applications. Validation of editing efficiency in genomic DNA research requires careful consideration of each component's properties and their interactions. The expanding repertoire of Cas nucleases with diverse PAM specificities, coupled with advances in gRNA design and delivery methods, provides researchers with unprecedented flexibility in genome engineering applications.

As CRISPR technology continues to evolve, integration with artificial intelligence and machine learning promises to further enhance the precision and efficiency of genome editing. The development of specialized systems like base editors, prime editors, and CAST systems addresses limitations of early CRISPR platforms, while anti-CRISPR proteins provide enhanced temporal control. By strategically selecting and validating the appropriate combination of CRISPR components for each experimental context, researchers can maximize editing efficiency while minimizing off-target effects, advancing both basic research and therapeutic applications.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by enabling precise, targeted modifications to the genome. This powerful gene-editing tool functions by introducing a site-specific double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA, after which the cell's own endogenous repair mechanisms are activated to resolve the break [11] [12]. The two primary competing pathways for repairing these CRISPR-induced breaks are Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). The fundamental difference between these pathways lies in their mechanisms and fidelity: NHEJ is an error-prone process that directly ligates broken ends, while HDR uses a homologous template for precise repair [13] [14]. Understanding the dynamics between NHEJ and HDR is crucial for researchers aiming to optimize CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency, particularly for applications requiring precise genetic modifications such as gene therapy, disease modeling, and functional genomics.

The competition between these pathways presents a significant challenge in genome engineering. In most eukaryotic cells, both repair pathways remain active; however, NHEJ generally dominates as it functions throughout the cell cycle and does not require a homologous template [14]. This inherent competition often results in low HDR efficiency, especially in non-dividing cells, making precise genome editing a considerable hurdle [13]. Consequently, developing strategies to enhance HDR efficiency or inhibit NHEJ has become a major focus in the field, requiring researchers to employ sophisticated validation methods to accurately quantify editing outcomes.

Molecular Mechanisms of NHEJ and HDR

The Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) Pathway

Overview and Biological Function Non-Homologous End Joining represents the dominant and most active DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells, functioning throughout all phases of the cell cycle but particularly predominant during G1 [11] [15]. As an error-prone repair mechanism, NHEJ directly ligates broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair site [12]. This characteristic makes NHEJ particularly suitable for gene knockout studies where the goal is to disrupt gene function by introducing frameshift mutations [12].

Key Molecular Steps and Protein Components The NHEJ pathway initiates when the Ku heterodimer complex (composed of Ku70 and Ku80 subunits) recognizes and binds to the broken DNA ends [13]. This complex then recruits and activates DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), forming a stable complex that protects the DNA ends from resection [11]. Subsequently, the Artemis:DNA-PKcs complex is activated and processes the DNA ends by removing overhangs, creating ligatable blunt ends [13]. In cases where nucleotide loss has occurred, DNA polymerases μ and λ fill in the gaps by adding missing nucleotides [11] [13]. The final ligation step is catalyzed by the DNA Ligase IV complex in conjunction with XRCC4 and XLF [11] [13]. This multi-step process, while efficient, often results in mutagenic outcomes due to the potential for nucleotide loss or addition during end processing.

Beyond the canonical NHEJ pathway, alternative end-joining mechanisms exist, including microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) which operates during S and G2 phases and relies on short homologous sequences (5-25 base pairs) for repair [11]. The MMEJ pathway involves different protein components including PARP1 for end recognition, MRN complex and CtIP for end resection, and Ligase I/III for the final ligation step [11].

Table 1: Key Protein Components of the NHEJ Pathway

| Protein Component | Function in NHEJ Pathway |

|---|---|

| Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer | Initial recognition and binding to DSB ends |

| DNA-PKcs | Recruitment and activation of processing enzymes |

| Artemis | Endonuclease activity for processing DNA overhangs |

| Polymerase μ and λ | Fill missing nucleotides at DSB ends |

| DNA Ligase IV | Catalyzes final ligation of broken ends |

| XRCC4/XLF | Stabilizes and enhances Ligase IV activity |

| 53BP1 | Promotes NHEJ pathway choice, particularly in G1 phase |

| PARP1 | Involved in alternative NHEJ pathways (MMEJ) |

The Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Pathway

Overview and Biological Function Homology-Directed Repair represents a precise, error-free repair mechanism that utilizes homologous DNA sequences as templates for accurate DSB restoration [12]. Unlike NHEJ, HDR is restricted to the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when sister chromatids are available as natural templates [14]. This cell cycle dependency significantly impacts HDR efficiency in various cell types, particularly post-mitotic cells where HDR rates are substantially lower [13]. Researchers leverage HDR for precise genetic modifications including gene knock-ins, point mutations, or insertion of tagged gene versions by providing exogenous donor templates with homology arms [12].

Key Molecular Steps and Protein Components HDR initiation begins with extensive 5' to 3' end resection of the DNA break, a process coordinated by the MRN complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1) in conjunction with CtIP [11]. This resection creates 3' single-stranded DNA overhangs that are essential for subsequent steps. The single-stranded DNA is rapidly bound and protected by Replication Protein A (RPA). BRCA2 then facilitates the replacement of RPA with RAD51, forming a nucleoprotein filament that catalyzes the central homologous pairing and strand invasion reaction [11]. This RAD51 nucleoprotein filament invades the homologous donor sequence, forming a D-loop structure that serves as a primer for DNA synthesis using the donor template. After DNA synthesis, the resulting intermediate structures are resolved through various subpathways including double-strand break repair (DSBR), synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), or break-induced replication (BIR), with SDSA being the predominant pathway mitigating crossover events in mitotic cells.

The choice between NHEJ and HDR is regulated by several key factors. 53BP1 promotes NHEJ by limiting DNA end resection, while BRCA1 antagonizes 53BP1 to favor HDR [11]. Additional regulators include TIRR, which masks the H4K20me2 binding surface targeted by 53BP1, and SCAI, which disrupts 53BP1-RIF1 interaction to promote HDR [11]. The POH1 deubiquitinating enzyme also contributes to HDR promotion by removing ubiquitin modifications that recruit 53BP1 [11].

Table 2: Key Protein Components of the HDR Pathway

| Protein Component | Function in HDR Pathway |

|---|---|

| MRN Complex | Initial DSB recognition and 5' to 3' end resection |

| CtIP | Cooperates with MRN complex in end resection |

| BRCA1 | Promotes HDR pathway choice; antagonizes 53BP1 |

| RPA | Binds and protects single-stranded DNA after resection |

| BRCA2 | Loads RAD51 onto single-stranded DNA |

| RAD51 | Forms nucleoprotein filament; catalyzes strand invasion |

| RAD52 | Facilitates strand annealing in alternative HDR pathways |

| TIRR | Promotes HDR by inhibiting 53BP1 recruitment |

Quantitative Comparison of NHEJ and HDR Efficiency

Systematic quantification of HDR and NHEJ outcomes reveals complex relationships between these competing pathways that are highly dependent on experimental conditions. Using a novel droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assay capable of simultaneously detecting HDR and NHEJ events at endogenous loci, researchers have demonstrated that the relative efficiency of these pathways varies significantly based on gene locus, nuclease platform, and cell type [15]. Contrary to the widespread assumption that NHEJ generally occurs more frequently than HDR, studies have found that more HDR than NHEJ can be induced under multiple conditions, with HDR/NHEJ ratios showing remarkable context dependency [15].

Kinetic studies in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) have revealed distinct temporal patterns for these repair pathways. HDR events plateau approximately 24 hours after Cas9 introduction, while NHEJ repair continues until 48 hours post-transfection [16]. Cut but unrepaired alleles reach their maximum level within 12-24 hours after DSB induction before gradually declining as repair processes complete [16]. These kinetic differences have important implications for experimental design, particularly regarding the optimal timing for analysis after CRISPR editing.

Cell type significantly influences pathway efficiency, with notable differences observed between naïve and primed pluripotent stem cells. Research demonstrates that the rate of HDR is approximately 40% lower in naïve hPSCs compared to conventional primed hPSCs, correlating with a higher proportion of naïve cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle where HDR is less active [16]. This finding contradicts earlier assumptions that naïve hPSCs might be superior for gene editing and highlights the importance of considering cell cycle distribution when planning HDR-based experiments.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of NHEJ and HDR Efficiencies Across Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Impact on NHEJ | Impact on HDR | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Type (naïve vs. primed hPSCs) | Similar levels observed | 40% lower in naïve hPSCs | Correlates with increased G1 population in naïve cells [16] |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Active throughout all phases | Restricted to late S and G2 phases | HDR efficiency cell cycle-dependent [14] |

| Repair Kinetics | Continues until 48 hours post-transfection | Plateaus after 24 hours | Unrepaired alleles peak at 12-24h [16] |

| Gene Locus | Variable depending on chromatin context | Variable depending on chromatin context | Locus-specific effects on HDR/NHEJ ratio [15] |

| Nuclease Platform | Varies with nuclease type | Varies with nuclease type | Affects HDR/NHEJ ratios [15] |

| Template Design (TFO-tailed ssODN) | Minimal direct effect | Increase from 18.2% to 38.3% | Enhanced spatial accessibility improves HDR [17] |

Experimental Strategies for Modifying NHEJ/HDR Balance

Molecular and Chemical Interventions

Researchers have developed multiple strategic approaches to enhance HDR efficiency by modulating the balance between NHEJ and HDR pathways. These interventions typically target three key aspects: inhibiting NHEJ components, stimulating HDR factors, or synchronizing the cell cycle to favor HDR [11].

NHEJ Inhibition Strategies Small molecule inhibitors targeting key NHEJ components have shown promise in improving HDR efficiency. Compounds such as SCR7 (targeting DNA Ligase IV) and KU0060648 (inhibiting DNA-PKcs) can effectively suppress the canonical NHEJ pathway, thereby reducing competing error-prone repair and increasing the relative frequency of HDR [11]. Additionally, genetic approaches including knockdown of 53BP1 or other essential NHEJ factors (Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs) through RNA interference can achieve similar effects, though these methods may be less practical for therapeutic applications [11].

HDR Stimulation Approaches Alternatively, enhancing HDR activity directly represents another viable strategy. RS-1, a small molecule activator of RAD51, can stimulate the core homologous pairing activity central to HDR, thereby increasing precise editing efficiency [11]. Timing Cas9 delivery to coincide with S/G2 phase through cell cycle synchronization protocols can also significantly boost HDR rates by ensuring the homologous repair machinery is active and accessible when DSBs occur [14].

CRISPR/Cas9 System Optimization

Cas9 Engineered Variants Substantial efforts have focused on engineering optimized Cas9 variants that favor HDR outcomes. These include chimeric Cas9 proteins fused with HDR-promoting factors, Cas9 nickase systems that generate single-strand breaks instead of DSBs, and modified Cas9 versions that can directly recruit the donor template to the cleavage site [11]. For instance, eCas9 and HiFi Cas9 variants offer improved specificity while maintaining robust on-target activity, with HiFi Cas9 demonstrating particularly favorable kinetics for HDR-based editing in stem cells [16].

Donor Template Design Innovations The design and delivery of donor templates significantly impact HDR efficiency. Recent research demonstrates that modifying single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) tails that form PolyPurine Reverse Hoogsteen (PPRH) hairpins can increase HDR efficiency from 18.2% to 38.3% by improving spatial accessibility of the donor template to the break site [17]. Optimization of homology arm length and strategic incorporation of silent mutations in the donor sequence to prevent re-cleavage of edited sites further enhance HDR outcomes [13].

Validation Methods for CRISPR Editing Efficiency

Accurate validation of CRISPR editing outcomes is essential for evaluating the efficiency of both NHEJ and HDR events. Various methods with differing sensitivities, advantages, and limitations have been developed for this purpose.

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay The T7E1 assay represents a traditional, cost-effective method for detecting NHEJ-derived indels. This approach relies on the T7 endonuclease I enzyme, which cleaves heteroduplex DNA formed when wild-type and mutant PCR amplicons are annealed [18] [19]. However, comparative studies have revealed significant limitations in T7E1 accuracy, particularly for detecting editing efficiencies above 30% or distinguishing between sgRNAs with similar activity levels [19]. When evaluated against next-generation sequencing, T7E1 consistently underestimated editing efficiency and failed to detect poorly performing sgRNAs with less than 10% NHEJ activity [19].

Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) TIDE analysis utilizes Sanger sequencing of edited populations followed by computational decomposition of the resulting chromatograms to quantify indel frequencies [19]. While TIDE shows improved correlation with next-generation sequencing results compared to T7E1, it can miscall alleles in edited clones and deviates by more than 10% from sequencing-predicted indel frequencies in approximately 50% of cases [19].

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Approaches Next-generation sequencing, particularly amplicon-based deep sequencing, provides the most comprehensive and quantitative assessment of CRISPR editing outcomes. NGS enables simultaneous detection of both HDR and NHEJ events with single-base resolution, sensitivity for alleles with frequency below 1%, and full characterization of complex editing patterns [15] [20]. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) offers an alternative highly sensitive quantification method capable of detecting one HDR or NHEJ event among 1,000 genomic copies, making it suitable for kinetic studies and precise efficiency measurements [15] [16]. High-throughput genotyping services like genoTYPER-NEXT leverage NGS to enable automated analysis of thousands of samples simultaneously, significantly streamlining the validation pipeline for large-scale CRISPR screening projects [20].

Table 4: Comparison of CRISPR Validation Methods

| Validation Method | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7E1 Assay | Enzyme cleavage of heteroduplex DNA | Limited, fails below 10% editing | Cost-effective; technically simple | Low dynamic range; underestimates high efficiency; subjective interpretation [19] |

| TIDE Analysis | Decomposition of Sanger sequencing chromatograms | Moderate | More accurate than T7E1; quantitative | Deviates >10% in 50% of clones; miscalls alleles [19] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Amplicon sequencing with high coverage | High (<1% allele frequency) | Comprehensive; quantitative; detects all variants | Requires bioinformatics; higher cost [20] [19] |

| Droplet Digital PCR | Probe-based quantification in partitioned samples | Very high (1 in 1,000 copies) | Absolute quantification; high precision; kinetic studies | Requires specific probe design; limited multiplexing [15] [16] |

Successful CRISPR genome editing experiments require careful selection of reagents and resources tailored to specific research goals. The following essential components represent the core toolkit for investigators working with NHEJ and HDR pathways:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR DNA Repair Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | Wild-type Cas9, Cas9 D10A nickase, Cas9 H840A nickase, FokI-dCas9 | Generate DSBs or nicks at target sites; different platforms affect HDR/NHEJ ratios [15] |

| Donor Templates | ssODNs, dsDNA donors with homology arms, TFO-tailed ssODNs | Provide repair template for HDR; design significantly impacts efficiency [17] |

| Pathway Modulators | SCR7 (Ligase IV inhibitor), KU0060648 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor), RS-1 (RAD51 activator) | Enhance HDR efficiency by inhibiting NHEJ or stimulating HDR components [11] |

| Validation Tools | T7E1 enzyme, ddPCR assays, NGS library prep kits | Detect and quantify editing outcomes; vary in sensitivity and throughput [15] [19] |

| Cell Line Models | HEK293T, HeLa, human iPSCs, mouse embryos | Different cell types show variable HDR/NHEJ ratios; selection impacts efficiency [15] [16] |

Visualizing the DNA Repair Pathway Decision Process

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and molecular interactions that determine whether NHEJ or HDR pathways are activated following a CRISPR/Cas9-induced double-strand break:

CRISPR-Induced DNA Break Repair Pathway Decision Map

Additionally, the following workflow diagram illustrates a modern experimental approach for quantifying and validating CRISPR editing efficiency:

CRISPR Editing Validation Workflow

The competition between NHEJ and HDR pathways represents a fundamental biological constraint that significantly impacts the efficiency and precision of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. While NHEJ operates as the dominant, error-prone pathway throughout the cell cycle, HDR provides a precise, template-dependent alternative restricted to specific cell cycle phases. The dynamic balance between these pathways is influenced by multiple factors including cell type, gene locus, nuclease platform, and experimental conditions [15].

Understanding these relationships enables researchers to develop strategic approaches for manipulating the repair pathway choice through small molecule inhibitors, optimized Cas9 variants, cell cycle synchronization, and innovative donor template designs [11] [17]. Concurrently, advances in validation methodologies, particularly ddPCR and NGS-based approaches, provide researchers with increasingly sensitive tools to quantify editing outcomes accurately and optimize experimental conditions [15] [16].

As CRISPR applications continue to expand toward therapeutic implementations, further elucidating the complex regulation of DNA repair pathways will remain essential for achieving predictable and precise genomic modifications. The ongoing development of strategies to enhance HDR efficiency while minimizing off-target effects represents a critical frontier in advancing both basic research and clinical applications of genome editing technologies.

The validation of CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency is a cornerstone of modern genomic research and therapeutic development. While the design of guide RNAs and the choice of Cas nuclease are critical, the ultimate editing outcome is not determined solely by these tools. Instead, it is profoundly influenced by the cellular environment and the methods used to deliver the editing machinery [2] [21]. This guide provides an objective comparison of how key biological and technical factors—specifically the cell cycle, delivery methods, and broader cellular context—govern the efficiency and precision of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, equipping researchers with the data needed to optimize their experimental strategies.

The Interplay of Cell Cycle and DNA Repair Pathways

At the heart of CRISPR/Cas9 editing is the creation of a DNA double-strand break (DSB), which the cell must repair. The choice of repair pathway is heavily constrained by the cell's position in the cell cycle, directly determining the editing outcome [2] [22].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, as it requires a sister chromatid template. This makes HDR, which enables precise gene knock-ins or corrections, highly inefficient in non-dividing, postmitotic cells [22].

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is active throughout the cell cycle and is the dominant pathway in postmitotic cells. It ligates the broken DNA ends together, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function [2] [22].

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ), another error-prone pathway, is also restricted to certain cell cycle stages (S/G2/M) and is predominant in dividing cells, leading to larger deletions [22].

Recent research reveals that DNA repair is not only cell-cycle-dependent but also varies by cell type. A 2025 study in Nature Communications demonstrated that postmitotic human neurons repair Cas9-induced DNA damage over a much longer timeframe (up to two weeks) compared to genetically identical dividing cells [22]. Furthermore, neurons exhibited a narrower distribution of indel outcomes, heavily favoring small indels typical of classical NHEJ, while dividing cells showed a broader range, including MMEJ-like larger deletions [22]. This fundamental difference in the DNA damage response underscores the critical importance of cellular context.

The diagram below illustrates how cellular context dictates the available DNA repair pathways and, consequently, the resulting editing outcomes.

A Comparative Analysis of CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Methods

The vehicle used to deliver CRISPR components is a major determinant of editing success, influencing everything from efficiency and specificity to immunogenicity. The three primary cargo types—plasmid DNA, mRNA/gRNA, and pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes—each present distinct advantages and limitations [21] [23].

The following table compares the most common delivery vehicles, their applications, and their documented editing efficiencies.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Vehicles and Their Performance

| Delivery Method | Cargo Type | Application Context | Reported Editing Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation (e.g., CASGEVY) [21] | RNP (preferred), mRNA | Ex vivo (e.g., HSCs, T cells) | Up to 90% indel frequency [21] | High efficiency for hard-to-transfect cells; direct delivery of RNP minimizes off-targets. | Can compromise cell viability; primarily suitable for ex vivo use. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [21] [24] | mRNA/gRNA, RNP | In vivo (systemic or local) | ~90% protein reduction (e.g., in hATTR trials) [24] | Biodegradable; low immunogenicity; potential for redosing; organ-targeted versions in development. | Requires endosomal escape; liver-tropic by default; editing efficiency depends on cargo. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) [2] [23] | DNA (plasmid) | In vivo, ex vivo | Varies widely; can be high with optimized systems [25] | Low immunogenicity; high transduction efficiency; tissue-specific serotypes. | Limited packaging capacity (~4.7 kb); can trigger immune responses; prolonged expression raises off-target risk. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) [22] [23] | RNP (protein) | Ex vivo, in vivo (preclinical) | Up to 97% transduction in iPSC-derived neurons [22] | Transient delivery; no viral genome integration; high efficiency for sensitive cells like neurons. | Manufacturing challenges; cargo size constraints; stability issues. |

| Adenoviral Vectors (AdVs) [23] | DNA (plasmid) | In vitro, ex vivo | Not quantified in results | Large cargo capacity (~36 kb); does not integrate into genome. | Can cause undesirable immune responses. |

| Lentiviral Vectors (LVs) [2] [23] | DNA (plasmid) | Ex vivo (common) | Not quantified in results | Can infect dividing and non-dividing cells; no cargo size limit. | Integrates into host genome, raising safety concerns for therapeutics. |

Cellular Context: A Determinant of Repair and Outcome

Beyond the cell cycle, the broader cellular context—encompassing cell type, tissue origin, and metabolic state—significantly influences editing outcomes through its effect on the native DNA repair machinery.

- Cell Type-Specific Repair Kinetics: As highlighted earlier, the 2025 study by [22] found that indel accumulation in human neurons continued for up to 16 days post-delivery of Cas9 RNP, a dramatically longer timeline than the 1-2 days typical in dividing cells. This prolonged repair process was also observed in other clinically relevant nondividing cells, such as cardiomyocytes and primary T cells in a resting state [22].

- Differential Repair Factor Expression: The same study demonstrated that neurons upregulate non-canonical DNA repair factors in response to Cas9 exposure compared to dividing cells. This unique repair signature presents both a challenge and an opportunity; by manipulating this response with chemical or genetic perturbations, researchers were able to direct DNA repair toward desired outcomes in neurons and cardiomyocytes [22].

- Implications for Experimental Design: These findings necessitate that editing strategies be tailored to the specific cell model. For example, achieving precise HDR in primary neurons is inherently difficult, making NHEJ-based gene knockout or newer base/prime editing approaches more viable. Furthermore, the extended timeline for full editing manifestation in non-dividing cells means that analysis performed too early may significantly underestimate editing efficiency [22].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Key Factors

To validate CRISPR/Cas9 efficiency in light of these factors, researchers can employ the following detailed methodologies, drawn from recent literature.

Protocol 1: Assessing Cell-Cycle Dependence of Editing Outcomes

This protocol is adapted from approaches used to compare dividing and non-dividing cells [22].

- Cell Preparation and Synchronization: Utilize a matched cellular model, such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and iPSC-derived postmitotic neurons, or activated vs. resting primary human T cells.

- CRISPR Delivery: Deliver a consistent dose of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. For neurons and resting T cells, use efficient vehicles like virus-like particles (VLPs) or electroporation, respectively. For dividing cells (iPSCs, activated T cells), electroporation or chemical transfection can be used.

- Longitudinal Sampling and Analysis: Harvest genomic DNA at multiple time points post-delivery (e.g., days 1, 2, 4, 7, 14). Amplify the target locus by PCR and analyze the editing outcomes using next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Data Interpretation: Quantify the percentage of indels over time and classify the types of mutations (small indels vs. large deletions). Compare the kinetics and distribution of outcomes between dividing and non-dividing cell populations.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Delivery Method Efficiency

This protocol provides a framework for comparing different delivery vehicles in a target cell type.

- Vehicle and Cargo Selection: Choose 2-3 relevant delivery methods (e.g., Electroporation of RNP, LNP-mediated mRNA delivery, Lentiviral transduction). Standardize the gRNA sequence and target locus across all conditions.

- Transfection/Transduction: Perform delivery according to optimized protocols for each method, ensuring consistent cell numbers and health status across conditions.

- Efficiency and Specificity Assessment: At 48-72 hours post-delivery (or later for non-dividing cells), harvest cells for analysis.

- Editing Efficiency: Isolate genomic DNA and perform T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay or, preferably, NGS to quantify indel percentage at the on-target site.

- Off-Target Effects: Use in silico prediction tools to identify potential off-target sites, followed by amplicon sequencing of those loci to assess off-target activity.

- Cell Viability: Perform a cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, flow cytometry with viability dye) 24 hours after delivery to assess cytotoxicity.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions for investigating the factors discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Workflow Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 RNP Complex | Pre-assembled complex of Cas9 protein and sgRNA; considered the gold standard for high efficiency and low off-target effects [21] [23]. | Ideal for electroporation and VLP delivery; transient activity; reduced cytotoxicity compared to plasmid DNA. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered delivery vehicle for RNP complexes; enables efficient transduction of hard-to-modify cells like neurons [22]. | Pseudotype (e.g., VSVG, BaEVRless) must be chosen for target cell type; allows transient RNP delivery without viral genome integration. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic nanoparticles for in vivo delivery of mRNA or RNP cargo; target organs like the liver [21] [24]. | Enable systemic administration; potential for redosing; efficiency depends on endosomal escape and cargo release. |

| Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) LNPs | Engineered LNPs with added molecules to alter tropism; can target spleen, lungs, or specific liver cell types [23]. | Emerging technology for expanding in vivo delivery beyond the liver. |

| T7 Endonuclease I Assay | Mismatch-cleavage assay for rapid, cost-effective detection of indel mutations [25]. | Semi-quantitative; less sensitive than NGS but useful for initial screening. |

| Single-Cell DNA Sequencing (e.g., Tapestri platform) | High-resolution analysis of editing outcomes (zygosity, complex structural variations) at the single-cell level [26]. | Reveals clonality and heterogeneity of editing that bulk sequencing masks; critical for safety assessment. |

The journey to a predictable and precise CRISPR/Cas9 editing outcome is multifaceted. This guide has underscored that successful genomic research and therapeutic development depend on a holistic strategy that integrates the cellular context, including cell cycle status and cell-type-specific repair mechanisms, with a rational selection of delivery methods based on cargo, target cells, and application. By adopting the detailed experimental protocols and leveraging the reagent solutions outlined here, researchers can systematically dissect and optimize these key factors, thereby enhancing the reliability, efficiency, and safety of their CRISPR-based genomic validations.

CRISPR-Cas systems have revolutionized genomic DNA research, offering unprecedented precision in genetic engineering. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate Cas enzyme is crucial for experimental success. This guide provides an objective comparison of three widely used nucleases—SpCas9, SaCas9, and Cas12a—focusing on their editing efficiency, specificity, and practical applications. The evaluation of these enzymes is framed within the broader thesis of validating CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency, presenting key performance data to inform reagent selection for specific genomic contexts.

Molecular Mechanisms and Key Characteristics

The CRISPR-Cas system functions as a programmable DNA-targeting complex. The Cas nuclease is directed to a specific genomic locus by a guide RNA (gRNA for Cas9; crRNA for Cas12a). Target recognition and cleavage are contingent upon the presence of a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site, which varies by nuclease [27] [28].

- SpCas9: Derived from Streptococcus pyogenes, it remains the most widely adopted nuclease. It requires a 5'-NGG PAM (where N is any nucleotide) downstream of its target sequence. Upon binding, its two nuclease domains create a double-strand break (DSB) with blunt ends [29].

- SaCas9: Isolated from Staphylococcus aureus, it recognizes a more complex 5'-NNGRRT PAM (where R is A or G). Its key advantage is a significantly smaller size (about 1 kb smaller than SpCas9), facilitating packaging into delivery vectors like adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) for therapeutic applications. It also produces blunt-ended DSBs [28] [29].

- Cas12a (formerly Cpf1): Representative variants include AsCas12a (Acidaminococcus sp.) and LbCas12a (Lachnospiraceae bacterium). This nuclease differs from Cas9 in several ways: it recognizes a T-rich 5'-TTTV PAM (where V is A, C, or G) upstream of the target, requires only a single crRNA without a tracrRNA, and introduces DSBs with staggered ends that create 5' overhangs [27] [28].

CRISPR-Cas Nuclease Workflow: This diagram illustrates the shared workflow of target recognition and cleavage by SpCas9, SaCas9, and Cas12a, highlighting the critical divergence at the PAM recognition and cleavage stages.

Comparative Performance Data

Direct comparisons of Cas nuclease efficiency under controlled conditions are critical for reagent selection. A study comparing nucleases in plants using identical regulatory elements and vector backbones found SaCas9 to be the most efficient at inducing mutations, though the nucleotide content of the target itself also correlated with efficiency [27]. Performance can also be organism-dependent; in rice calli, SpCas9 was the most efficient nuclease at both 27°C and 37°C, whereas AsCas12a showed no detectable activity under the tested conditions [30].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Common Cas Nucleases

| Feature | SpCas9 | SaCas9 | Cas12a (As/Lb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Streptococcus pyogenes [29] | Staphylococcus aureus [29] | Acidaminococcus sp. / Lachnospiraceae bacterium [27] |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' [30] | 5'-NNGRRT-3' [28] [30] | 5'-TTTV-3' [27] [30] |

| Guide RNA | sgRNA (crRNA + tracrRNA) [29] | sgRNA (crRNA + tracrRNA) [28] | crRNA only [27] |

| Cleavage Type | Blunt ends [29] | Blunt ends [29] | Staggered ends (5' overhangs) [27] |

| Protein Size | ~1368 aa (large) [29] | ~1053 aa (small) [29] | ~1300 aa (large) [27] |

| Reported Editing Efficiency | High (e.g., >95% in HEK293T with optimal gRNAs) [31] | High efficiency; found "comparatively most efficient" in one plant study [27] | Variable; can be highly efficient with optimized crRNAs [32] |

| Specificity & Off-Targets | Moderate; improved by high-fidelity variants [27] [31] | Can exhibit high specificity; engineered variants available [29] | Generally high specificity; can be enhanced with modified crRNAs [32] |

| Key Advantage | Well-characterized, versatile, extensive toolkit [29] | Small size ideal for viral delivery (e.g., AAV) [29] | Simplified guide RNA, staggered ends for HDR [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Validating the efficiency of CRISPR-Cas editing requires standardized and reliable experimental workflows. Below are detailed protocols for two common assessment methods.

Protocol 1: Transient Assay in Plant Protoplasts for gRNA Screening

This protocol, adapted from a study in maize, is designed to rapidly evaluate the performance of multiple gRNAs or nucleases before undertaking stable transformation [33].

- Target Site Selection & gRNA Design: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPRdirect, CRISPOR) to identify potential target sites with minimal off-targets in the genome of interest [28].

- Construct Assembly: Clone selected gRNA or crRNA sequences into appropriate CRISPR expression vectors. Using a unified vector system for different nucleases minimizes experimental variability [28].

- Protoplast Isolation:

- Harvest young leaves or embryonic tissue.

- Digest cell walls using enzyme mixtures (e.g., cellulase and macerozyme) to release protoplasts.

- Purify protoplasts through filtration and washing.

- Protoplast Transformation:

- Incubate purified protoplasts with the CRISPR plasmid DNA constructs.

- Use polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transformation to introduce the DNA.

- Incubate the transformed protoplasts in the dark for 48-72 hours to allow for gene editing to occur.

- DNA Extraction & Analysis:

Protocol 2: Evaluating Editing in Rice Callus at Different Temperatures

This protocol assesses how temperature, a critical environmental factor, influences the activity of different Cas nucleases [30].

- Vector Construction: Assemble vectors encoding the nuclease (e.g., SpCas9, SaCas9, AsCas12a) and their respective guide RNAs using a modular cloning system. The nuclease should be driven by a constitutive plant promoter like OsUbi2 [30].

- Stable Transformation:

- Use biolistic transformation to deliver the constructed vectors into embryogenic rice calli (e.g., cultivar Taipei 309).

- After transformation, transfer calli to selection media containing hygromycin to select for transformed events.

- Temperature Treatment:

- Divide the selected calli into two groups.

- Incubate one group at 27°C (standard plant tissue culture temperature) and the other at 37°C (reported optimal temperature for many bacterial Cas nucleases) for the duration of the experiment.

- Genotyping and Efficiency Calculation:

- After a suitable incubation period, harvest calli and pool them for genomic DNA extraction.

- Amplify the target locus via PCR and subject the amplicons to high-throughput sequencing.

- Analyze sequencing data to calculate the percentage of modified reads, distinguishing between monoallelic and biallelic edits [30].

Nuclease Selection Logic: This diagram outlines the primary delivery methods available for different nucleases and the key application considerations that should guide the selection process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful CRISPR experiment design and execution relies on a core set of reagents and tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Expression Vector | Provides a backbone for the expression of the Cas nuclease and guide RNA in cells. | Use standardized, modular systems (e.g., Golden Gate Assembly-compatible) for seamless testing of different nucleases and targets [28]. |

| Endogenous Promoters | Drives the expression of CRISPR components in the host organism. | Using highly expressed, species-specific promoters (e.g., LarPE004 in larch) can significantly boost editing efficiency over standard viral promoters [34]. |

| Modified Guide RNA Scaffolds | Optimizes guide RNA structure to enhance stability and expression. | Replacing the standard 4T-sequence in the gRNA scaffold with a 3TC sequence can significantly increase gRNA transcript levels from U6 promoters, boosting editing efficiency, especially for difficult targets or with limited vector [31]. |

| Chemically Modified crRNA | Enhances stability and performance of Cas12a crRNA. | Using crRNA with a ribosyl-2'-O-methylated uridinylate-rich 3'-overhang improves Cas12a dsDNA digestibility and increases editing efficiency and specificity in zygotes and cell lines [32]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery vehicle for in vivo CRISPR therapy. | LNPs are effective for delivering CRISPR components to the liver and have been used successfully in clinical trials for systemic administration, with the advantage of allowing re-dosing [24]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | A delivery vehicle for in vivo gene therapy. | The small size of SaCas9 makes it particularly suited for AAV delivery, enabling targeted in vivo editing in tissues like the liver and nervous system [29]. |

Advanced Engineering and Clinical Applications

The continuous engineering of Cas enzymes has expanded their utility and performance, paving the way for clinical applications.

- High-Fidelity Variants: Engineered versions of SpCas9 (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) and SaCas9 (e.g., SaCas9-HF) have been developed to reduce off-target effects by incorporating mutations that decrease non-specific interactions with DNA, which is critical for therapeutic safety [27] [31] [29].

- AI-Designed Editors: Artificial intelligence and large language models are now being used to design novel CRISPR-Cas proteins with optimal properties. These AI-generated editors, such as OpenCRISPR-1, can exhibit comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being highly divergent in sequence [6].

- Therapeutic Breakthroughs: CRISPR-based medicines have transitioned to the clinic. Casgevy, a therapy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, was the first to receive approval. Furthermore, in vivo treatments are showing remarkable success, such as LNP-delivered Cas9 therapies for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) and hereditary angioedema (HAE), which achieve deep, sustained reduction of disease-causing proteins in the liver [24].

The choice between SpCas9, SaCas9, and Cas12a is not a matter of identifying a single superior enzyme, but rather of selecting the right tool for a specific experimental or therapeutic goal. SpCas9 remains a versatile and powerful workhorse for many applications, while SaCas9's compact size makes it ideal for viral delivery. Cas12a offers a distinct mechanism with its simple guide RNA and staggered cuts. Critical evaluation of editing efficiency must account for factors such as target sequence, delivery method, and host organism. The ongoing development of high-fidelity and AI-designed nucleases, coupled with promising clinical data, underscores the dynamic nature of this field and the continuous evolution of the CRISPR toolkit for genomic research and medicine.

From Design to Delivery: Practical Strategies for Achieving High-Efficiency Genome Editing

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized genomic DNA research by providing an unprecedented ability to perform targeted genome editing. At the heart of this technology lies the guide RNA (gRNA), a short nucleic acid sequence that directs the Cas9 nuclease to specific genomic locations. The design of this gRNA represents perhaps the most critical determinant of experimental success, as it must achieve two often competing objectives: high on-target efficiency to ensure effective editing at the intended locus, and sufficient specificity to minimize off-target effects that could compromise experimental results or therapeutic applications [35] [36].

For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the complex landscape of gRNA design requires understanding the computational tools, design parameters, and validation strategies that collectively ensure reliable outcomes. This challenge is particularly acute in therapeutic contexts, where off-target mutations could have serious clinical consequences. The fundamental components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system include the Cas9 nuclease and a synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that combines the functions of crRNA (which provides target specificity through a 20-nucleotide guide sequence) and tracrRNA (which serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding) [37] [38]. Successful targeting requires both base pairing between the gRNA and target DNA and the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence immediately adjacent to the target site—typically 5'-NGG-3' for the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) [35] [38].

Key Parameters for Optimal gRNA Design

Predicting and Maximizing On-Target Efficiency

On-target efficiency refers to the capability of a gRNA to direct Cas9-mediated cleavage at the intended genomic location. Multiple studies have identified specific sequence features that correlate with high editing activity, leading to the development of various predictive algorithms. Research has consistently demonstrated that nucleotide composition at specific positions within the gRNA significantly influences efficiency. For instance, guanine at position 20 (adjacent to the PAM) and cytosine at the variable position of the PAM site are associated with higher activity, while poly-N sequences (especially consecutive guanines) tend to reduce efficiency [35].

The following features have been identified as significant modulators of cleavage efficiency:

- Position-specific nucleotides: G or A at position 19; C at positions 16 and 18; G at position 20; avoidance of U at positions 17-20 [35]

- Overall nucleotide usage: Preference for A counts; avoidance of excessive G or U counts [35]

- Motifs: Favorable dinucleotides include AG, CA, AC, and UA; unfavorable dinucleotides include UU and GC [35]

- GC content: Optimal range between 40-60%; efficiency drops significantly with GC content exceeding 80% [35] [39]

- PAM preference: CGG PAM sequences show higher efficiency than TGG [35]

Several scoring systems have been developed to quantitatively predict gRNA efficiency based on these features, with the Rule Set series (Rule Set, Rule Set 2, and Rule Set 3) being among the most widely adopted. Rule Set 3, published in 2022, incorporates the tracrRNA sequence into its model and uses a gradient boosting framework trained on data from 47,000 gRNAs, showing improved predictive accuracy over earlier versions [37]. Other notable efficiency prediction algorithms include CRISPRscan, based on in vivo validation of 1,280 gRNAs in zebrafish, and Lindel, which employs a logistic regression model trained on approximately 1.16 million mutation events to predict insertion and deletion patterns resulting from Cas9 cleavage [37].

Ensuring Specificity and Minimizing Off-Target Effects

Off-target effects occur when Cas9 cleaves at genomic sites with significant similarity to the intended target sequence, potentially leading to unintended mutations and confounding experimental results. The specificity of a gRNA is influenced primarily by the number and position of mismatches between the gRNA and potential off-target sites, with mismatches closer to the PAM-distal region (positions 1-8) being more tolerant than those near the PAM-proximal region (positions 12-20) [37] [35].

Three principal methods have emerged for assessing off-target potential:

- Homology Analysis: This approach identifies sequences across the genome with significant similarity to the gRNA, with particular attention to those fitting the PAM sequence and having fewer than three nucleotide mismatches. Sequences with only one mismatch indicate high off-target potential, while those with two or three mismatches should be limited as much as possible [37].

- MIT Specificity Score: Also known as the Hsu-Zhang score, this method was developed based on data from over 700 gRNA variants with 1-3 mismatches and provides a quantitative assessment of off-target risk [37].

- Cutting Frequency Determination (CFD): Developed by Doench et al. in 2016, CFD uses a scoring matrix based on the activity of 28,000 gRNAs with single variations. CFD scores below 0.05 (or sometimes 0.023) are generally considered to indicate low off-target risk [37].

Recent advances in specificity analysis include GuideScan2, which employs a novel algorithm using the Burrows-Wheeler transform for memory-efficient genome indexing and exhaustive off-target enumeration. This tool has demonstrated a 50× improvement in memory efficiency compared to its predecessor while maintaining high accuracy in identifying potential off-target sites [40].

Comparative Analysis of gRNA Design Tools

Researchers have access to numerous computational tools for gRNA design, each with distinct strengths, scoring methodologies, and applications. The table below provides a comparative analysis of major design platforms:

Table 1: Comparison of Major gRNA Design Tools

| Tool | On-Target Scoring | Off-Target Scoring | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPick | Rule Set 3 | CFD | Simple interface; updated logic from large-scale experiments; supports SpCas9 and AsCas12a | Knockout, CRISPRi, CRISPRa [37] |

| CHOPCHOP | Rule Set, CRISPRscan | Homology analysis | Visual off-target representations; supports various CRISPR-Cas systems; batch processing | Multiple species and applications [37] [36] |

| CRISPOR | Rule Set 2, CRISPRscan | MIT, CFD | Detailed off-target analysis with position-specific mismatch scoring; restriction enzyme sites for cloning | Experimental cloning considerations [37] |

| GuideScan2 | Not specified | Custom specificity scoring | Memory-efficient genome indexing; handles non-coding regions; allele-specific gRNA design | Genome-wide screens, non-coding targeting [40] |

| GenScript sgRNA Design Tool | Rule Set 3 | CFD | Overall score balancing multiple parameters; transcript coverage; downstream ordering capability | SpCas9 and AsCas12a designs [37] |

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of various prediction tools across multiple datasets spanning different cell types and species. Deep learning models such as CRISPRon and DeepHF have demonstrated superior performance compared to conventional machine learning approaches, exhibiting greater accuracy and higher Spearman correlation coefficients across diverse experimental conditions [41]. However, the optimal tool choice often depends on the specific application, as performance can vary across cell types and species [35].

Experimental Validation of Editing Efficiency

Validation Methodologies

Computational predictions of gRNA efficiency and specificity must be confirmed through experimental validation. Several methods have been established for this purpose, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Comparison of gRNA Validation Methods

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7E1 Assay | Detects structural deformities in heteroduplexed DNA | Low to moderate (saturates at ~30% efficiency) | Cost-effective; technically simple; easy interpretation | Underestimates high efficiency; requires heteroduplex formation; subjective interpretation [19] |

| TIDE Analysis | Decomposes sequencing chromatograms to quantify indels | Moderate | Quantitative; provides information on indel types; no special equipment | Can miscall alleles in clones; deviations >10% in 50% of clones [19] |

| IDAA | Uses fluorescent primers to detect length variations | Moderate | Medium-throughput; size resolution | Can miscall alleles; accurately predicted only 25% of indel sizes and frequencies [19] |

| Targeted NGS | High-throughput sequencing of target locus | High (gold standard) | Most accurate; identifies precise indel sequences; broad dynamic range | Higher cost; computational requirements [42] [19] |

A comprehensive study comparing these validation methods revealed significant discrepancies in their estimates of editing efficiency. The T7E1 assay consistently underestimated efficiency, particularly for highly active gRNAs, and failed to distinguish between sgRNAs with substantially different activities. For example, two sgRNAs (M2 and M6) that showed approximately 28% activity by T7E1 demonstrated dramatically different efficiencies by targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS)—40% for M6 versus 92% for M2 [19]. These findings highlight the importance of using sensitive validation methods, with targeted NGS emerging as the gold standard for accurate quantification of editing efficiency.

Recommended Validation Workflow

Based on comparative studies, the following workflow is recommended for validating gRNA editing efficiency:

- Initial screening using the T7E1 assay or TIDE analysis for rapid assessment of multiple gRNA candidates

- Quantitative validation of selected gRNAs through targeted NGS for accurate efficiency measurement and indel characterization

- Off-target assessment using specialized methods such as GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq for therapeutic applications where comprehensive off-target profiling is essential

This workflow balances practical considerations with the need for accurate efficiency quantification, ensuring reliable selection of high-performing gRNAs for downstream applications.

Advanced Strategies for Enhanced Specificity

Addressing the Challenges of Complex Genomes

The challenges of gRNA design are particularly pronounced in organisms with complex genomic architectures. For example, wheat—a hexaploid crop with a large genome size (17.1 Gb) and high repetitive DNA content (>80%)—requires specialized design strategies to ensure specificity across homologous subgenomes [39]. Successful approaches include:

- Comprehensive homology analysis using tools like WheatCRISPR to identify unique target sites with minimal off-target potential across subgenomes

- Leveraging pan-genome databases to design cultivar-specific gRNAs or target conserved regions across varieties

- Structural analysis of gRNA properties including secondary structure, Gibbs free energy, and self-complementarity to optimize functionality [39]

These principles can be extended to other complex genomes, including mammalian systems, where repetitive elements and gene families present similar challenges for specific targeting.

Emerging Approaches: AI-Designed Editors and Specificity Enhancement

Recent advances have introduced novel strategies for enhancing CRISPR specificity. Large language models (LMs) trained on diverse CRISPR-Cas sequences have demonstrated the ability to generate highly functional genome editors with optimal properties. For instance, the AI-designed OpenCRISPR-1 exhibits comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations away in sequence space [6]. This approach bypasses evolutionary constraints to create editors with tailored properties.

Additionally, the development of high-specificity gRNA libraries through tools like GuideScan2 has revealed confounding effects in published CRISPR screens, where low-specificity gRNAs produced strong negative fitness effects even for non-essential genes, likely through toxicity from non-specific cuts [40]. Newly designed libraries that prioritize specificity while maintaining efficiency demonstrate reduced off-target effects in essentiality screens, highlighting the importance of specificity-oriented design for reliable genetic screening.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| TrueGuide Synthetic gRNAs | Pre-designed, validated gRNAs for specific targets | Human AAVS1, HPRT, CDK4; Mouse Rosa26; negative controls [42] |

| GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit | Rapid estimation of CRISPR cleavage efficiency | Gel-based detection of indels in pooled cell populations [42] |

| CRISPR Plasmids | Expression vectors for gRNA and/or Cas9 | Available from repositories such as AddGene; enable customizable gRNA expression [38] |

| Cas9 Variants | Engineered nucleases with enhanced properties | High-fidelity variants; altered PAM specificity; orthogonal systems [6] [19] |

| gRNA Design Software | Computational selection of optimal gRNAs | CRISPick, CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR, GuideScan2 [37] [40] |

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for gRNA design and validation that integrates the principles and tools discussed in this guide:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive gRNA Design and Validation Workflow

Achieving optimal balance between on-target efficiency and specificity requires a systematic approach that integrates computational design with experimental validation. By leveraging the expanding toolkit of design algorithms, validation methods, and novel CRISPR systems, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their genome editing experiments. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning approaches promises to further refine our ability to design highly functional gene editors with minimal off-target effects, accelerating both basic research and therapeutic development.

The transformative potential of CRISPR-Cas9 in genomic DNA research and therapeutic development is undeniable, yet its success is profoundly influenced by the method chosen to deliver its molecular components into target cells. The delivery strategy directly dictates key outcomes, including editing efficiency, specificity, and cell viability [43]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the optimal delivery platform is a critical step in experimental design and therapeutic translation. The three primary cargo formats—plasmid DNA, Cas9 messenger RNA (mRNA) with guide RNA (gRNA), and pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes—each present a distinct profile of advantages and limitations [43]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these methods, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of validating CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency for robust genomic research. By integrating recent experimental data and detailed protocols, we aim to equip scientists with the evidence needed to make an informed choice for their specific application.

Performance Comparison of Delivery Methods

The choice of cargo format influences nearly every aspect of a CRISPR experiment. The table below summarizes a direct comparison of key performance metrics, synthesizing data from multiple recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Cargo Formats

| Feature | Plasmid DNA | mRNA + gRNA | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Efficiency | Variable; can be lower due to reliance on transcription/translation [44] | High; faster than plasmids [43] | Consistently high; often the highest reported efficiency [45] [44] |

| Specificity (Off-target Effects) | Higher risk due to prolonged Cas9 expression [44] | Lower than plasmids due to transient activity [43] | Highest specificity; minimal off-targets due to rapid degradation [46] [44] |

| Toxicity & Cell Viability | Can be stressful and cytotoxic; viability often reduced [44] | Generally low toxicity and good biocompatibility [43] | Notably less cytotoxic; maintains high cell viability (>80%) [45] [44] |

| Onset of Editing | Slow (24-72 hours); requires transcription and translation [44] | Faster than plasmids; requires only translation [43] | Most rapid (a few hours); Cas9 is immediately active [44] |

| Risk of Foreign DNA Integration | Yes; random integration of plasmid fragments can occur [47] | No (if using synthetic RNA) | No; non-viral, DNA-free editing [44] [47] |

| Key Supporting Data | 30% unwanted plasmid integration in chicory study [47] | Efficient editing with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [43] | 50% KI efficiency in CHO-K1 cells; 58.3-87.5% precise editing with NanoMEDIC [45] [46] |

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic differences and cellular fates of these three cargo formats, which underpin their performance characteristics.

Experimental Data and Protocols

Case Study: Evaluating Delivery Methods in Chicory